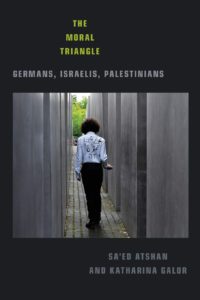

Searching for Reconciliation in Berlin

A book review of The Moral Triangle: Germans, Israelis, and Palestinians

A demonstration protesting antisemitism at Berlin’s Brandenburg Gate. (Photo: Thomas Peter)

I first learned about The Moral Triangle: Germans, Israelis, and Palestinians a year ago when, during dinner with one of its authors (Sa’ed Atshan), I mentioned that my partner had just returned from Berlin on a vacation I did not take with her. I told Sa’ed the reason I didn’t go with her was that, despite my rational understanding of Berlin as a cosmopolitan city, rich with memorial commemorations of its Jewish heritage, and one where the Germans were more likely to be “philo” rather than “anti” Semites, I was still reluctant to set foot there.

I grew up in the 1950s boycotting German products even though my family lost no one in the Holocaust, was not religious, and my one German-Jewish grandparent, who was born in Indiana in the 1880s and whom I adored, told me often of her love for all things German. More rationally, as a staunch supporter of the Palestinian non-violent Boycott, Divestment, and Sanctions (BDS) movement, I was not enamored with the way Germans expressed their sense of ethical obligation to Jews by making moral and financial restitution for the Holocaust through their unwavering commitment to Israel – a commitment that inevitably required supporting its apartheid-like treatment of Palestinians.

Sa’ed, who is himself Palestinian, being ever gentle and always looking for ways to make peaceful interventions, told me I was missing out by refusing to open my eyes and see Berlin in its contemporary light. In that context he told me about the book he had recently co-authored with a Jewish friend, Katharina Galor. He had decided to respond to her invitation to conduct a sociological study of Germans, Israelis, and Palestinians in Berlin because of Germany’s exemplary model of restorative justice towards Israel, no matter what its flaws. They wanted to find out how such a model was affecting Israelis, Palestinians, and Germans in Berlin and how these groups were coming to terms with the relationships that existed among them in that place. I thought my partner would surely be interested in reading the book, even if I would not. I ordered an advance copy for her, and left it at that.

Fast-forward to pandemic life. When the book arrived this June, it sat in quarantine for several days. I gave it to my partner, whose work life has been so crazed she has yet to have the time to read it. But the longer it sat on her armchair next to mine, the more I thought I should take a look.

I am glad I did and encourage you to as well. You will not only see how the authors have done research that is at once scholarly and political; you will also discover two special people whose connection to each other exemplifies the goal of their work: to teach us that we must listen to others and traverse differences to do so. As we learn in the book’s postscript, Katharina is an Israeli Jew who was raised in Germany in the 1960s and 1970s, and whose vivid memories of growing up with virulent antisemitism there shaped her life’s work. She left Germany after high school and did not expect to go back. But when her husband accepted a position in Germany she hesitantly returned. What she discovered in Berlin was a drastically changed society, both in its extraordinary culture and in the way the government and people have made restitution for the Holocaust and antisemitism. Yet she found herself troubled by certain aspects of the efforts at reparation: the Germans’ unquestioning allegiance to Israel, their ignorance of the Palestinians’ situation, and their disregard for how the Holocaust contributed to Palestinian suffering. Katy knew that what was transpiring in Berlin among Germans, Israelis, and Palestinians would make an interesting study of a complex moral dilemma, and she embarked on an investigative journey that became a fascinating book.

I am glad I did and encourage you to as well. You will not only see how the authors have done research that is at once scholarly and political; you will also discover two special people whose connection to each other exemplifies the goal of their work: to teach us that we must listen to others and traverse differences to do so. As we learn in the book’s postscript, Katharina is an Israeli Jew who was raised in Germany in the 1960s and 1970s, and whose vivid memories of growing up with virulent antisemitism there shaped her life’s work. She left Germany after high school and did not expect to go back. But when her husband accepted a position in Germany she hesitantly returned. What she discovered in Berlin was a drastically changed society, both in its extraordinary culture and in the way the government and people have made restitution for the Holocaust and antisemitism. Yet she found herself troubled by certain aspects of the efforts at reparation: the Germans’ unquestioning allegiance to Israel, their ignorance of the Palestinians’ situation, and their disregard for how the Holocaust contributed to Palestinian suffering. Katy knew that what was transpiring in Berlin among Germans, Israelis, and Palestinians would make an interesting study of a complex moral dilemma, and she embarked on an investigative journey that became a fascinating book.

When she asked Sa’ed to join her, he was reluctant at first. He was raised as a Quaker in the West Bank, and his life there was shaped by his experiences at Ramallah Friends School, where he learned about the Holocaust and the evils of antisemitism. As a result of this early training he also had to overcome his own aversion to spending time in Germany. As a student, and later as a professor at Swarthmore College, Sa’ed maintained relationships with American Jews (myself among them) and focused his personal and academic life on the pursuit of peace and justice. He ultimately agreed to contribute to this project because, like me, he was deeply moved by Katy’s vision and intrigued by her question about how this moral triangle between Israelis, Palestinians, and Germans could be better understood. Upon arriving in Germany, Sa’ed was delighted to be well received in Berlin as a queer person. But he was deeply dismayed by how he was treated as a Palestinian and how little Palestinian pleas for justice are understood there, especially since Palestinians have long seen the Holocaust as the source of their trauma, even if the Germans do not.

Although it was Sa’ed’s and Katy’s stories that moved me the most deeply, they would likely insist that this book is not about them, but about the Berliners they came to meet. In that they would be correct also. Getting to know their interlocutors and marveling at the range of voices the authors were able to represent fairly, including characters it was not easy for me to like (Islamophobic Germans, antisemitic Palestinians, and right-wing Israelis), was key to the core idea of this book — that we need to listen to each other in order to reshape the moral triangle among Germans, Israelis, and Palestinians to achieve a better balance among the three groups. Hearing their voices allows the reader to view this story from all of their perspectives and in all its complexities.

Palestinian protest at Berlin’s Brandenburg Gate. (Photo courtesy of Getty Images)

The book’s title also matters: the image of a moral triangle sets up the authors’ big question. As I read, I began to puzzle over what this triangle among Germans, Israelis, and Palestinians in Berlin might actually look like. After all, triangles come in three main shapes. Was this triangle equilateral, isosceles, or scalene, I wondered? While what first comes to mind is the equilateral, picturing a triangle with three equal sides is not well suited to this story. It’s obvious that the German side would be longer, and probably situated at the top. The story is set in their country, they have the most power as citizens, and it all began with their sense of themselves as perpetrators of the “original sin,” the Holocaust.

One might then imagine this moral triangle is isosceles, with Israelis and Palestinians on sides of equal length. But the real story the authors tell here is that the triangle is scalene, and has 3 unequal sides. Israelis in Berlin have the second longest side, even though there are fewer of them than Palestinians, because of the German propensity to treat Israelis as if they were the only Jewish victims of German aggression in World War II. Of course this is problematic. After all, the Jews in Israel are not by any means always the descendants of Holocaust victims or survivors. Furthermore, Israelis are not only Jewish, but also Christian and Muslim. And Jews who live in other places never received the kind of attention from Germany that it has lavished on the state of Israel.

But there is a bigger problem in the inequality that the lopsided triangle revealed. What the authors learned in their interviews was that focusing on Israel obscured the Palestinian viewpoint for most of the Germans, even the progressive ones. The Israeli and Palestinian sides of this moral triangle are not equal because the Germans can only see themselves as perpetrators and Israelis as victims, making it difficult for them to sympathize with Palestinians and their liberation struggle. As the authors recount, many of the Palestinians “spoke about their frustration that it does not register for most Germans that their country’s genocide of Jewish Europeans played a fundamental role in causing Palestinians’ displacement from Palestine.”

But there is a bigger problem in the inequality that the lopsided triangle revealed. What the authors learned in their interviews was that focusing on Israel obscured the Palestinian viewpoint for most of the Germans, even the progressive ones. The Israeli and Palestinian sides of this moral triangle are not equal because the Germans can only see themselves as perpetrators and Israelis as victims, making it difficult for them to sympathize with Palestinians and their liberation struggle. As the authors recount, many of the Palestinians “spoke about their frustration that it does not register for most Germans that their country’s genocide of Jewish Europeans played a fundamental role in causing Palestinians’ displacement from Palestine.”

The good news the book brings is that progressive Israelis are trying to change the story and are working for equal rights for Palestinians in Berlin. They are playing a crucial role in reshaping the triangle, and the authors believe Germans can begin to recognize how the Holocaust changed the world for both groups.

I found the stories the authors elicited quite moving and, as I noted, I found myself fascinated by the authors themselves, what they experienced doing this work, and the conclusions they drew from it. In chapter 11, we learn that Sa’ed planned to give a lecture in Berlin about being queer and Palestinian in East Jerusalem. But his lecture had to be moved from Berlin’s Jewish Museum because of pressure put on the institution by German officials and representatives of the Jewish community. They did not want a Palestinian to lecture in a Jewish space, no matter what the topic. Katy’s distress over Sa’ed being censored in a Jewish space resonated for me. I witnessed Sa’ed go through a similar experience in Philadelphia. Here, ironically, Sa’ed was disinvited from a Quaker space, although also as a result of Jewish communal pressure. Perhaps this is the most depressing of all: that a person who seeks peace and pursues it with passion, and who is open to conversations with anyone who will listen respectfully, should not be heard. It reminds us that we have a long way to go in our efforts toward mutual understanding.

But in the book’s conclusion, the authors give us hope. They bring a powerful message that, at least in Berlin, the work of reconfiguring this moral triangle is beginning. After all their conversations and research, the authors make the recommendation that projects of restorative justice like the one Germany has pursued in its response to the Holocaust can be a model for how things could get better. Restorative justice is not animated by guilt as motive for repair, but by acknowledging that justice is the goal. But to get there requires recognition of moral wounds.

Ultimately this book persuaded me that what is happening in Berlin in the realm of rethinking the concepts of moral responsibility is special, and I should, at the least, reconsider my aversion to going there and seeing it firsthand.

Rebecca Alpert is a Professor of Religion at Temple University in Philadelphia.

***

Published with support from the Henry R. Luce Initiative on Religion in International Affairs.