Writing about Healthcare, Religion, and Equality

A conversation with Ann Neumann about her column, The Patient Body, her book, The Good Death, and her writing about healthcare, vulnerability, and religion.

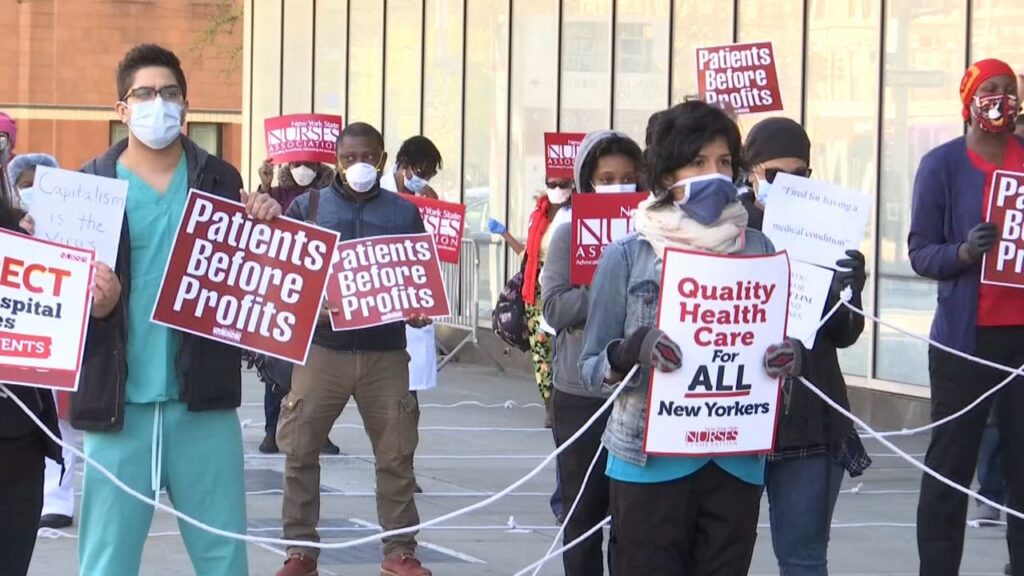

(Image source: CNN)

Ann Neumann was the Revealer’s editor from 2010 to 2013, when she left to write her brilliant book, The Good Death: An Exploration of Dying in America. When I took over as editor of the magazine, Ann wrote 50 installments of “The Patient Body,” a monthly column from 2013 to 2018 about religion and medicine, on everything from organ donation to assisted suicide to Down’s syndrome. About halfway through that impressive run, she and I sat down for a conversation in which we discussed religion, the medical industry, and more. Coming into 2022, the Revealer’s current editor, Brett Krutzsch, had the idea for us to reconnect and talk about what Neumann’s been up to in the last few years. Unsurprisingly, she remains both busy and deeply committed to the issues she’s been writing about for years. She has also been covering fascinating and urgent new topics, taking her interests in healthcare, religion, and equity to issues occurring around the world.

Kali Handelman: It was so much fun to go back through the archive of your work at the Revealer and to start the process of catching up on your current writing — I loved seeing the ongoing themes — bodily autonomy, the brokenness of American healthcare, death and dying — and the new questions you’ve been pursuing. Can you tell us a bit about how you see that trajectory, where you left off with “The Patient Body” and The Good Death, and what you’re most excited about in your work now?

(Ann Neumann)

Ann Neumann: When I look at the expanse of the Patient Body series, I’m amazed by how much ground we covered. I think the column really benefited from our process: I’d suggest some curiosity like, What’s all this new legislation surrounding Down’s syndrome and neonatal testing? Then I would go find out what it was about. It’s to your credit that I was able to run with my own interests in that way, because you had to do a lot of shaping sometimes. You brought more disciplined thinking to the stories I was trying to tell. The combination of curious questioning and smart editing worked well. I think that’s how I still work best, following my curiosity. To be sure, it’s the least comfortable way to work because it’s always uncertain.

I was just talking about this with Kathryn Joyce, a brilliant investigative journalist who was once at NYU’s Center for Religion and Media (the Revealer’s publisher) and is now on staff at Salon. We were talking about how hard it is to write about something you’re an expert in, as if the more you know short circuits the fine craft of writing. Too much information gets in the way. But the uncertainty of new questions can bring it right back. It pays off in better writing to always be pushing out into new areas. Keep your key “old saws” close, know what they are, but always keep reaching out to new lenses, subjects, territories.

I have learned over the years that I am most grounded when my work is close to the body. Whether I’m writing about elder care or reporting on aid in dying, talking with others about their experiences, their embodiment, is what engages me. But I found about two years ago that having been on the same beat for so long, having established some kind of expertise in the subjects of death and dying, my writing was less interesting, more stagnant. I was giving talks, writing newsy pieces that were important but not exciting to me. I wanted to be reporting in a way that taught me things. I did some extensive nursing home work during the pandemic and that was good, but in the past year I’ve been pivoting to other areas that I know so little about. Areas where I am looking for the religion and the bodies.

KH: I love that — the religion and the bodies! I’m definitely going to ask you about that pivot to new work, but first, can you tell me more about how religion continues to play a part in your reporting?

AN: Religion will always be central to anything I do, not because of who I am but because — say it loud! — religion is at the core of our lives and cultures, our politics and geopolitics, certainly our health care and social services. Dare me to find the religion in almost any story!

Maybe the best way to describe how I think about religion is to start with how we currently talk about what is systemic. Recently, there’s been a lot of such talk, although askance. When we’re talking about Critical Race Theory, for instance, we’re debating what racism is and how it works in American society: is race a personal issue, how someone behaves, or is it a belief that’s been built into our systems? Clearly the latter. And it’s fair to say that religious ideas and preoccupations are also systemic, shaping our lives in incalculable ways. With religion, some of those ways are good, but clearly not all.

And this is something that Anthea Butler, the religion scholar at the University of Pennsylvania and author of White Evangelical Racism, gets so right: responsibility for injustice is not just individual but also collective. In this country we’re hung up on the I. I’m not racist, I’m hard working, I have black friends, I believe. In this way, we avoid culpability for entrenched injustices and even dismiss them as unimportant. No bad apple? No problem. Often those doing the dismissing are working within systems, within cultures deeply embedded with racism, like Evangelicalism, like the carceral system, like banking, like the healthcare system. Our supposed American self-reliance — I am my own self-made man — becomes an excuse to ignore our responsibility for systemic problems. This works historically as well. You see it again in the Critical Race Theory debates: that’s in the past, we’re not responsible, can’t you just let it go, you’re dividing us. Don’t fall for it! Personal responsibility, in the church or outside it, is not going to change corrupted systems.

This seems an impossible thing for us to learn because our sense of individual selves is so merged with our go-it-alone national identity, our national pride in reinvention (putting a slip on the past!), and innovation (always looking forward!). Indeed we’re quite good at forgetting our original sins — preferring to whip them into some shuffle of nostalgia and “tradition” — and at getting born again.

KH: Yes, I think you’re absolutely right. And I think we probably also see this focus on systems and responsibility in some of your recent work. You’ve done some really critical (in both senses of the word: essential and asking challenging questions) reporting on the COVID-19 pandemic. You’ve written about everything from the plights of nursing home workers and the long history of pandemics, to the global drug supply chain and vaccine intellectual property. I’d be interested in hearing about how the work you did on death and dying has carried through into your perspective on the pandemic.

AN: This is so kind of you. I mean, part of the challenge of these overlapping Trump and pandemic years has been the feeling of futility. I was just starting a whole new project when COVID chased us into our homes and the work turned out to be very relevant to the moment. I had an editor at The Guardian call me in the fall of 2019 and ask if I wanted to look into a common narrative, one that had picked up speed in various media: nursing homes, particularly in rural areas, were closing en masse, scattering their residents to the wind, far from spouses and loved ones. But I turned the piece down. You just can’t write about nursing home care in the U.S. without knowing your shit on Medicare and Medicaid. But when she hit me up a few months later, I had been watching the industry for a little while and I had learned more. She made it clear that she wanted race and economic inequality (two foundational issues within healthcare that I always try to address in my work) to be a major part of the piece. I was hooked. I was reporting on nursing homes in Philadelphia, a city with one of the largest low-income elder populations in the country, in February 2020, weeks before the pandemic hit the U.S.

AN: This is so kind of you. I mean, part of the challenge of these overlapping Trump and pandemic years has been the feeling of futility. I was just starting a whole new project when COVID chased us into our homes and the work turned out to be very relevant to the moment. I had an editor at The Guardian call me in the fall of 2019 and ask if I wanted to look into a common narrative, one that had picked up speed in various media: nursing homes, particularly in rural areas, were closing en masse, scattering their residents to the wind, far from spouses and loved ones. But I turned the piece down. You just can’t write about nursing home care in the U.S. without knowing your shit on Medicare and Medicaid. But when she hit me up a few months later, I had been watching the industry for a little while and I had learned more. She made it clear that she wanted race and economic inequality (two foundational issues within healthcare that I always try to address in my work) to be a major part of the piece. I was hooked. I was reporting on nursing homes in Philadelphia, a city with one of the largest low-income elder populations in the country, in February 2020, weeks before the pandemic hit the U.S.

As we all watched news clips of bodies being wheeled out of nursing homes, what I knew to be truer than anything else was that these deaths were preventable. The industry had all the warning signs, years ago. Chronic problems like understaffing and other austerity practices directly led to the unfathomable number of COVID deaths inside facilities the country over. These deaths were preventable. But why weren’t they prevented?

That question has fueled almost everything I’ve done since the start of the pandemic. The drug supply chain, the intellectual property laws preventing governments outside the West from vaccinating their people? I want to know why the lives of some — a clearly identifiable some! — are structurally (systematically, again) less protected, less defended, less valued than other lives. We know the broad reasons — apathy, structural racism, corporate greed, the lack of profit in emergency planning — but if we know what the obstacles are, why are they still so insurmountable? Not claiming I have an answer, but that nursing home narrative about rampant closures? True. It checked out; there are a large number of facilities closing across the country. But it’s because there’s no buyer and seller oversight. Not only because reimbursement rates are low. In fact, studies show that when you raise Medicare and Medicaid reimbursement rates for nursing homes, the quality of care doesn’t improve. Private equity for the past decade or so has been coming in and sucking the life out of nursing home chains. Often these private equity firms buy facilities by the dozen, then sell the real estate out from under them, forcing the operators of the homes to pay rent. It’s a huge challenge because the margin in the nursing home business is already slim. Yes, state and federal funding should be higher, yes it’s a beleaguered industry, but government oversight could have stanched the problem. And when they didn’t, states could have stepped in. Nobody came for these people.

KH: Which leads naturally, and painfully, to my next question. While reading your recent work, it struck me that one of the deepest through lines is an interest in vulnerability. You write with deep sensitivity and outrage about the experiences of people whose lives are precarious because of poverty and illness, but also, importantly, the ways our systems not only fail to mitigate these harms, but in fact profit off of them. I would love to know if you see vulnerability as a central theme in your work and if so, why? How does that question motivate you and determine the stories you tell and the way you tell them?

AN: Woah, vulnerability! Seriously, I’ve always told myself that it was something much narrower motivating me: I thought it was unwanted pain I’ve been writing against. Unwanted pain and suffering. You’ve reminded me of this Revealer article, in which I characterize the thankfully late Phyllis Schlafly, “Real women, unlike those whimpering feminists relentlessly proclaiming the cost of their labors, suffer and toil in silence.” There are dark and heavy moments in my personal history — and we all have them — that were deeply painful. That’s at least part of having a body, of embodiment, and yes, particularly a female body. So identifying — even anticipating — sources of pain seems like an outrageously obvious human imperative. The pain of others should outrage us. And when we are experiencing pain, others owe us outrage at what causes us pain.

But you’re onto something. Vulnerability is a precursor to pain, like a warning. It’s like what all the nursing home advocates were telling me about infection control weeks before COVID. Here are the vulnerabilities and the vulnerable, they said. Here is the pain, their illnesses and deaths, COVID said.

Vulnerability is generally really obvious. I mean we could, with broad strokes, identify the primary causes of pain and suffering in the world. Me and you, right now. We know who is vulnerable. Yet it’s a warning that we collectively have failed to heed. And you’re right, this is our inability to connect the personal to the system. Nursing home staff members do it better than anyone I know. A woman can be working a nursing home ward for 10 years, know all the people in it, and still provide poor care if she’s given too many patients. The problem isn’t the quality of her work, it’s the system that chooses to understaff the facility for profit, placing her care and that of her patients below the margin. The vulnerable register systemic pain and injustice in their bodies. Their caregivers can be the best in the country, but the system, predicated on austerity and designed by specialty accountants, as surgical as Robert McNamara at war, can still reach those residents.

(Image source: NY1)

Registering the vulnerable is also just a common precept of good journalism, which I try to practice: make large issues personal by following the life of an individual caught inside the problem. Ask them what hurts, what happened. Believe them when they tell you. What is more compelling than that? What is more human than that?

KH: Your ideas about systemic and personal vulnerability also makes me think about our many conversations over the years (I’m thinking in particular of this piece from the autumn of 2015, “Mortality and the American Dream”) about the particular, peculiar, power of “The American Dream.” This is a real softball question (I kid), but what do you think is the status of that dream right now? Where is it most alive? Where is it most frayed or fragile? How is that discourse being deployed? Does religion still play a big part in that deployment?

AN: Lordy that’s a rant! (Great art, by the way.) Yesterday The Baffler published a piece I wrote about chronic understaffing at hospitals, how and why understaffing persists. When I posted the piece on Facebook, a friend wrote to say that underpaid hospital jobs were all about choice. These poorly paid (predominantly Black and Latinx female) employees needed to make better choices. When I pushed back he did the predictable thing, used himself as an example, a guy who did well despite obstacles because he kept trying.

The American Dream stuff that made me so angry back in 2015 isn’t going anywhere soon. It’s still alive in Trumpland because that’s part of what Trumpland runs on, a mythic beautiful past that, when restored by moral behavior and hard work, will make America #1 in the beautiful future. But it’s also alive in regular good folks like my friend. And the less possible it is to bootstrap yourself out of debt or a 70 hour work week or rationing medication to feed your kids, the more tenaciously we seem to cling to the dream. I get hopeful when I see Starbucks and REI employees unionizing, and when I see cash bail and other carceral systems challenged. But, so many of our personal and political relationships are predicated on the kind of hierarchy — if you fail it’s your fault — that keeps the false dream alive. And let’s be clear, I’ve internalized the American Dream too. I feel like my successes are my own too often, that hard work will save me, that I’m behind if I’m not moving ahead.

Whenever we’re talking about morality in this country, I think we’re talking about a particular fusion of god and country. Today’s post-Trump patriot isn’t fighting for democracy and freedom (certainly not for freedom of the press or for personal freedoms), he’s fighting for economic austerity and a theocratic policing of the other, any other. He’s in a fight club for the fight. And he’s laser focused on limiting what country means (real Americans) and what god means (basically male-policed heteronormativity). Although our formulation is unique, we’re seeing the use of revanchist religiosity, austerity, and issues like racial and gender equality elsewhere in the world. In Putin’s Russia, certainly. The politics of nationalism tell us who among us deserves what they have, based on all kinds of measurements — race, age, beauty, education. This has so very little to do with moral behavior when the hardest working people are so clearly also the least able to get by financially.

Also in 2015 I wrote an article for my column about Sara Moslener’s book, Virgin Nation: Sexual Purity and American Adolescence, in which she neatly traces the idea that female morality was foundational to the success of the country. Moslener writes, “The progress of America as a nation-state… was dependent upon the proper negotiation of gendered roles and morality.” So every time you hear about evangelicals passing an anti-trans bill, an anti-abortion bill, an anti-childcare bill that will keep mothers at home, the goal is not only to elevate their own ideology but to do so in order to save this country. That’s some righteous shit. We laugh at Pat Robertson when he says the gays caused 9/11. But the man is a blunt voice saying the quiet part out loud.

KH: Honestly, “saying the quiet part out loud” is a pretty spot on summary of where we can find “the religion” these days. But rather than end on that doozy, I still want to hear more about what you’re working on next — where is your curiosity currently leading you?

AN: I’m working on a new book that is the perfect bridge between my death and dying work and more global interests. I feel like the Left has forgotten that the rest of the world exists and that disturbs me, when the rest of the world is so very close technologically, politically, culturally. The book begins with my father’s death (just like The Good Death) but takes another path, using grief as a catalyst for examining American identity, following a long trip I took after he died, while mourning and questioning my own identity. I say this all the time, but grief is inherently vain; we are reimagining ourselves in the absence of a person who meant so much to us. But travel, displacement from whatever we call home, is also a reimagining. How we are perceived becomes a vehicle, an assumption, a calculation of global hierarchies. With an American passport you can go many places others can’t. So what it means to be (it must be said) a small, blond, female American changes depending on where in the world you are.

The book is ostensibly about the actions of our myopic empire over the course of the past 60 years and the human and personal costs of our real and mythic well-being. This national narrative is very present, as I travel through Russia or Egypt or Tanzania, places where I am perhaps white first, female second, and American third. And therefore Christian. It’s been wonderful and absolutely unsettling to give up working within my own modest expertise, to venture out into physical and emotional areas I have been thinking about for a long time.

By the time this interview is published, I’ll be back from a four week trip to Cairo and Addis Ababa for two of my favorite outlets, Harper’s and The Baffler. For the former I’m writing about the war in Ethiopia — a country which has a personal resonance for me; my father was stationed in Eritrea, what was then Ethiopia, in the 1960s, on an American military base that was spying on the Russians, first their space program and then during the lead up to the Cold War. His work at “Stonehouse” was classified and he never talked about it. But Ethiopia stayed with him always. I have all his family letters and ephemera from that time. His story of “service” is a compelling insight into not only our country at that time, culturally and politically, but into Ethiopia. America’s presence there played a heavy role in the Eritrean war for independence from Ethiopian oppression, a war that birthed the country’s current president, perhaps one of the most authoritarian rulers in the world today. Ideas of cultural hierarchy, religious civilization, rights to bodies of humans, and water and land all come into play in this story.

Ethiopia and the United States’ relationship was forged in the post-WWII, pre-Cold War era, but the warped understanding our government had of Ethiopians — our lighter skinned Christian allies — long persisted, even thrived during the War on Terror. So much of this history is missing from news reports of the 15-month war there. I hope my piece will bring historical context and nuance back to the narrative of the Ethiopian war.

For the The Baffler I’m writing about the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam, built in Ethiopia to generate massive amounts of electricity, which the current prime minister promises will raise Ethiopians out of poverty. But ancient treaties, brokered by colonial powers, prevented Ethiopia from making use of the Nile for centuries. Ethiopia moved ahead with construction unilaterally and the dam has brought the historically fraught relations between Egypt and Ethiopia to a head. There are reports of Ethiopians being assaulted on the streets of Cairo. As you might guess, the U.S. has played a role in dam infrastructure in the Horn of Africa and Egypt.

Both of these stories are related to the book in expansive ways. It’s an ambitious project, an intimidating admission I don’t make to myself very often. But what book isn’t at the beginning?, I ask myself. Check back next spring and I’ll tell you where I am.

Kali Handelman is an academic editor based in London. She is also the Manager of Program Development and London Regional Director at the Brooklyn Institute for Social Research and a Contributing Editor at the Revealer.

Ann Neumann is author of The Good Death, published by Beacon Press.