Why I Share My Story: Vulnerability, Representation & Empowerment

Being public is a political decision rooted in love and directed toward helping others see what they do not experience themselves.

In 2011, after a particularly egregious case of racial profiling at airport security, I felt compelled to share my experience so people would know how bad TSA policies are for visible minorities, especially those who ‘look Muslim.’ I posted my story on Facebook and received an overwhelming response of love and support from my friends. But it was a phone call from a close friend I’d known since high school that really moved me. “I’m so sorry that you had to deal with that,” he said. “I can’t believe that happened to you.”

I was stunned. And the words just flew out of my mouth. “Really? You’ve been one of my best friends forever. I can’t believe you didn’t know that stuff happens to me all the time.”

After a few moments of uncomfortable silence, he responded sheepishly. “I’m really sorry, man. I didn’t know. You never really talk about this stuff, so I figured it didn’t affect you.”

I accepted his explanation, got over my surprise, and we moved forward in our conversation, catching up on everything else in our lives. But after we hung up I couldn’t get his words out of my head. For two weeks, I thought about it obsessively, engaging anyone willing to discuss the topic. And every night before going to bed, I would stare at the question I had written at the top of an otherwise blank page: “Have I been doing a poor job of dealing with racism this whole time?” Underneath that, in small, crooked letters: “What is my responsibility here? How can I actually be helpful?”

I began doing the only thing I knew in situations like this. I reflected on my own experiences and read voraciously.

Through this reflection and reading, I gradually realized that my friend was right. I did have a tendency to downplay the racism I experienced. I felt guilty sharing stories about discrimination against me because they seemed trivial compared to what others have endured. I kept my experiences to myself for the most part, occasionally sharing them with my wife or siblings if I felt particularly threatened. But I never shared them with publicly, not even with my friends. I didn’t want anyone thinking that I was making everything about me, or that somehow I felt like what I was enduring was worse than what others endured. I felt like it would be selfish for me to say anything.

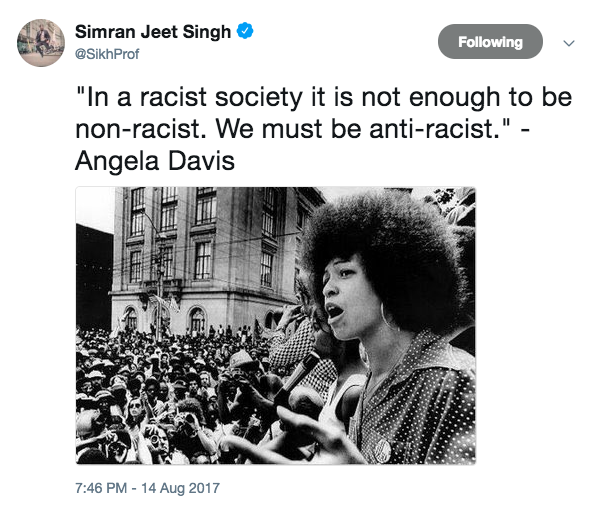

My new realization pushed me to read the work of luminaries. I wanted wisdom on how to improve my approach. I encountered a powerful line from a 1979 speech by Angela Davis, a black activist and philosopher whose work I admire deeply. “In a racist society, it is not enough to be non-racist. We must be anti-racist.” Her words were a sharp slap in the face, leaving an imprint that has lasted for years. Here I was, trying to live quietly, a good guy who experienced racism but never dealt it out to anyone. But I was not doing anything to actually address it address it. I was shook.

Silence is complicity, I learned. And if you’re not part of the solution, you’re part of the problem. I had never thought of it that way. But I knew she was right. And I knew I had to change course immediately.

Despite accepting her wisdom, I still struggled at figuring out what to do. My essential dilemma was this: in order to truly help people understand the pervasiveness of racism in our society, I would have to make myself vulnerable and begin sharing my own personal experiences. Describing this as new territory for me would be an epic understatement. Expressing emotion publicly had not been part of my upbringing, and I worried about how sharing these stories might change the ways that other people viewed me. The Sikh faith teaches us to be resilient and to strive for optimism in all situations. I have never viewed myself as a victim, and I worried that people who heard my stories might see me as one. Our Sikh faith also places a great deal of value on humility, and it felt wrong to call attention to myself in order to educate others. I struggled and struggled and struggled. And then, two things happened that helped me break through.

First, I came across an insight in Conversations with James Baldwin that brought together the jumbled pieces of my puzzled mind. “If I love you, I have to make you conscious of the things you don’t see.” I realized that I could share my own stories with the inspiration of love and with the intention to educate and advance justice — without it having to be about myself. This single sentence helped me break through months of struggle and shed light on what I had to do: If I truly loved the people around me, I would actually have to overcome my personal insecurities and open myself up to the world. I made a commitment to myself then and there: I would no longer hide the racism that I encountered. I would use the privilege that I enjoy in this world to help others learn about what people in my community — and other communities — endure in modern America. I resolved to publicly share every encounter with racism, from personal hate to structural discrimination, in order to do my part in opening the hearts and minds of people around me.

So I started sharing, primarily via online channels. I shared when the TSA racially profiled me at airports and subjected me to additional security screenings. I shared when a volunteer refused to serve me water during the New York City Marathon because I was a “filthy Muslim.” I also shared when a young man yelled racial slurs at me while I was commuting home. Yet the more I shared, the more I realized that I couldn’t completely control the narratives once I presented them. For example, I could only do so much to prevent myself, or people in my community, from being presented as victims. A vast majority of news coverage on Sikh Americans comes in response to incidents of discrimination, hate, or violence. And a vast majority of those stories present Sikhs as helpless victims who deserve public sympathy. I struggle with representations like that, because although they are well intended, they fail to authentically capture or represent how we view ourselves. Even the most well-conceived and carefully nuanced pieces about the experiences of Sikhs in America incorporated hate as a central narrative, including W. Kamau Bell’s piece for his CNN program, United Shades of America, Hasan Minhaj’s segment for The Daily Show, and Arun Venugopal’s New York Times feature on Sikhs emerging in American political leadership.

So I started sharing, primarily via online channels. I shared when the TSA racially profiled me at airports and subjected me to additional security screenings. I shared when a volunteer refused to serve me water during the New York City Marathon because I was a “filthy Muslim.” I also shared when a young man yelled racial slurs at me while I was commuting home. Yet the more I shared, the more I realized that I couldn’t completely control the narratives once I presented them. For example, I could only do so much to prevent myself, or people in my community, from being presented as victims. A vast majority of news coverage on Sikh Americans comes in response to incidents of discrimination, hate, or violence. And a vast majority of those stories present Sikhs as helpless victims who deserve public sympathy. I struggle with representations like that, because although they are well intended, they fail to authentically capture or represent how we view ourselves. Even the most well-conceived and carefully nuanced pieces about the experiences of Sikhs in America incorporated hate as a central narrative, including W. Kamau Bell’s piece for his CNN program, United Shades of America, Hasan Minhaj’s segment for The Daily Show, and Arun Venugopal’s New York Times feature on Sikhs emerging in American political leadership.

I admit there was something reassuring about finally seeing Sikhs presented in traditional media outlets as protagonists, as sympathetic figures, as people deserving better than what they received. This was undoubtedly a mark of progress for us as a community, particularly because we had felt invisible and unnoticed for so many decades. Yet there was something deeply unsatisfying about reading articles that presented our community in a way that didn’t resonate with our experiences. Moreover, the constant framing of Sikhs as victims flattens our complexities and ultimately prevents others from seeing us as fully human. This dissatisfaction motivated me to work even harder to open up space in the world of traditional media. I continued to try, speaking to reporters and writing opinion pieces that reiterated the point that there was no such concept of victimhood in the Sikh vocabulary. I soon realized, though, that one can’t fully control how people receive information, let alone how they choose to connect with experiences of others that are not their own. I realized that I was treading a fine line between wanting to share incidents of discrimination affecting our community while also wanting to not be seen as victims. I tried to shape these stories to strike that balance and even talked reporters through the issue when I got the chance. And although it’s been difficult to get it quite right every time, I believe that being aware of and negotiating those two concerns has, at the very least, improved how Sikhs are covered and perceived within the American context.

The more I shared, the more I saw people rally around me and my community. When my father and I were accosted in the parking lot after a San Antonio Spurs game last year, I tweeted about it from the safety of our car. I opened up my phone when we arrived home to see an overwhelmingly positive response on my Twitter feed. A few reporters from the local media picked up the story, which caught the attention of people in our local community and even from the Spurs organization itself. A team official called me immediately to offer support and condolences and to ask how the organization could be helpful. This type of emergent solidarity confirmed my belief that people are ultimately good and they want to do the right thing. I realized that many people were moved to stand with us the moment they learned about our experiences. This helped affirm my faith in humanity and in the work of sharing my experiences. As my father used to always tell us, “Make sure to count your blessings. It’s the best way to remember that there is far more light in this world than darkness.”

The more I shared, the more I saw people rally around me and my community. When my father and I were accosted in the parking lot after a San Antonio Spurs game last year, I tweeted about it from the safety of our car. I opened up my phone when we arrived home to see an overwhelmingly positive response on my Twitter feed. A few reporters from the local media picked up the story, which caught the attention of people in our local community and even from the Spurs organization itself. A team official called me immediately to offer support and condolences and to ask how the organization could be helpful. This type of emergent solidarity confirmed my belief that people are ultimately good and they want to do the right thing. I realized that many people were moved to stand with us the moment they learned about our experiences. This helped affirm my faith in humanity and in the work of sharing my experiences. As my father used to always tell us, “Make sure to count your blessings. It’s the best way to remember that there is far more light in this world than darkness.”

The more I shared, the more I regretted my previous approach of downplaying the racism I encountered. I still understood why I had taken that approach, but I thought of all the lost opportunities. So many of my friends in high school still live in Texas where I grew up and have been privileged enough not to have first-hand experiences of racism and its pernicious effects. I wished that instead of telling them to “let it go,” I had allowed my teammates to back me up when opponents yelled slurs at me. It would have given them a chance to see experiences outside of their own, and to practice being good allies and standing up for others. I wished I had shared my stories with people younger than me to let them know that they were not alone in their struggles with discrimination. I still feel guilty for not speaking up when I could have — and should have — knowing now that doing so may have prevented others from perpetuating the cycle of hate. I wish I knew then what I know today: that racism is systemic and structural and pervasive and, and that the only way to deal with it is to confront it directly and intersectionally.

The more I shared, the more I also realized the immense power of telling one’s own stories. I felt that, for the first time ever, I was able to get people to pay attention to my life experiences. I felt validated. I felt whole. I felt powerful. And I felt like I was building power with my community. And I’m not alone in this work. For the first time since Sikhs began coming to America over 125 years ago, we are starting to tell our own stories in the media. We are receiving representation. We have a voice. And we can use that voice to lift up members of our community, for political advocacy, and to help lift up others who were marginalized.

Certainly we still have a long way to go, especially given how grossly underrepresented and mistreated Sikhs still are today. But we are heading in the right direction. And this progress continues to fuel my public work and online presence, in spite of the vulnerabilities and challenges that come with participating in that world. For me, the very act of being public is a political decision rooted in love, grounded as service, and directed as a commitment to help others see what they do not experience themselves.

***

Simran Jeet Singh a Visiting Scholar at NYU’s Center for Religion and Media and a Senior Religion Fellow for the Sikh Coalition, a civil rights organization based in New York City. He is a columnist for the Religion News Service, on the board for Religion News Association, and he serves as a consistent expert for reporters around the world. Simran is a chaplain at New York University and serves on Governor Cuomo’s Interfaith Advisory Council for the State of New York. He is also a fellow for the Truman National Security Project, a term-member for the Council on Foreign Relations, and an Honorary Fellow at the University of Birmingham (UK). Simran holds graduate degrees from Harvard University and Columbia University, and he is the author of Covering Sikhs, a guidebook to help journalists accurately report on the Sikh community. He tweets at @SikhProf.

***

Published with support from the Henry R. Luce Initiative on Religion in International Affairs.