Who’s Afraid of the Free Speech Fundamentalists?: Reflections on the South Park Cartoon Controversy

Recent days have, alas, been marked by a sense of déjà vu all over again for scholars of contemporary Islam. On April 14th, the American cable network Comedy Central aired the first half of a double episode of the immensely-popular cartoon sitcom “South Park.” The episode specifically parodied Islamic prohibitions on the pictorial representation of the Prophet Muhammad by portraying him in concealment, first within a U-Haul truck and then inside an ursine mascot costume. On the day prior to the episode’s airing, the American website revolutionmuslim.com posted the following comments by one Abu Talhah al-Amrikee: We have to warn Matt and Trey [Matt Stone and Trey Parker, co-creators of South Park] that what they are doing is stupid and they will probably wind up like Theo Van Gogh for airing this show. This is not a threat, but a warning of the reality of what will likely happen to them.

by Jeremy F. Walton

Recent days have, alas, been marked by a sense of déjà vu all over again for scholars of contemporary Islam. On April 14th, the American cable network Comedy Central aired the first half of a double episode of the immensely-popular cartoon sitcom “South Park.” The episode specifically parodied Islamic prohibitions on the pictorial representation of the Prophet Muhammad by portraying him in concealment, first within a U-Haul truck and then inside an ursine mascot costume. On the day prior to the episode’s airing, the American website revolutionmuslim.com posted the following comments by one Abu Talhah al-Amrikee:

We have to warn Matt and Trey [Matt Stone and Trey Parker, co-creators of South Park] that what they are doing is stupid and they will probably wind up like Theo Van Gogh for airing this show. This is not a threat, but a warning of the reality of what will likely happen to them.

Al-Amrikee’s comments were accompanied by an image of Van Gogh’s body; the Dutch enfant terrible filmmaker was assassinated in Amsterdam by a Dutch-Moroccan extremist in November of 2004. In spite of al-Amrikee’s insistence that his posting did not constitute a threat, the inclusion of the image of Van Gogh, as well as the addresses of Comedy Central offices and a Colorado home co-owned by Stone and Parker, strongly suggested otherwise. In partial response to al-Amrikee’s post, Comedy Central opted to censor all references to Muhammad in the second half of the episode, which aired on April 21st. And so a familiar script was established: As in 1989 with the controversy over Salman Rushdie’s Satanic Verses (popularly known as “The Rushdie Affair”), as in 2005 with the global uptake of the caricatures of the Prophet Muhammad published by the Danish daily Jyllands-Posten, so too in 2010. Almost immediately, the complex theological and political issues at hand were reduced to a regrettable polarization of two mutually-exclusive fundamentalisms: stringent religious orthodoxy and free speech. My modest aspiration in this reflection is to attempt to think beyond the either-or of rigid orthodoxy and free speech—an admittedly difficult task in a political context that privileges the comfortable satisfactions of easy dichotomies.

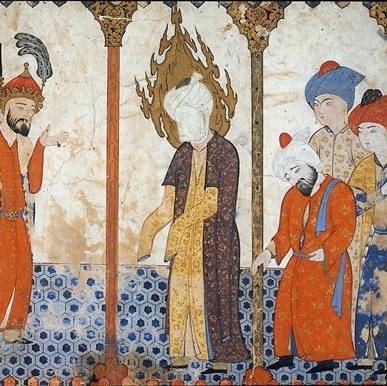

Theologically, the “South Park” episode in question is far from transparent. There is a double irony to the brewing controversy: First, the history of Islam itself encompasses a variety of traditions and arguments relating to the depiction of Muhammad; and, secondly, the “South Park” wags were exceptionally careful not to portray Muhammad in the episode, at least in any clear, incontrovertible way. Erroneous generalizations about Islam’s “iconophobia” are common media fodder these days. A brief BBC piece on the “South Park” episode flatly proclaims that “Muslims consider any physical representation of their prophet to be blasphemous. But such blanket proclamations obscure, for example, the tradition of Persian and Ottoman miniature paintings that depict Muhammad, his face often obscured by flames, not to mention other creative reconciliations between aesthetic practice and theological principle.

Of course, such nuances do not seem to be of much interest to the firebrand commentators on revolutionmuslim.com either, and this is a point that deserves emphasis: The mass-media production of controversy tends to support the efforts of political and theological extremists to monopolize collective identities such as ‘Islam’. From a brief perusal of the website, it is clear that revolutionmuslim.com is at least as concerned with radical anti-imperialist political rhetoric and mobilization against American foreign policy in Muslim countries as it is with Islamic theology. Of course, theology is important to the argument that revolutionmuslim.com makes against “South Park”, but the arguments mounted by the website’s commentators are hardly incontestable. In a broader response to the episode published after al-Amrikee’s provocation attracted media attention, Younus Abdullah Muhammad cites authoritative Sunni jurists such as Imam Malik and Ibn Taymiyyah to assert unequivocally that insulting the Prophet Muhammad is a crime in Islam punishable by death. While Abdullah Muhammad’s argument thus seems to rest on firm theological and jurisprudential ground, there is a decisive issue that he glosses over entirely: What procedures establish the “South Park” episode as an insult to the Prophet Muhammad? In other words, does insulting Muslim attitudes about the Prophet amount to an insult against the Prophet himself?

Abdullah Muhammad takes it for granted that ”South Park” insults Muhammad (not just Muslims), but, having watched the episode myself, I would argue that its status as blasphemous insult is far from clear. After all, the episode is careful to cue the viewer to the fact that Muhammad is not portrayed (and, incidentally, this alone distinguishes “South Park” from Kurt Westergaard’s infamous depiction of Muhammad with an ignited bomb in his turban). Furthermore, other characters treat Muhammad (who is depicted only in the aforementioned bear costume or, later, covered by a black box that reads “Censored”) with exceptional respect. This deference stands in stark contrast to the portrayal of other religious figures in the episode—the viewer is treated to the indelible tableau of the Buddha snorting formidable lines of cocaine while Jesus surfs the internet for porn. In short, one might contend that the episode does not clearly insult Muhammad. The episode is not necessarily blasphemous in a theological sense even if it does succeed in offending many Muslims. With the distinctive sort of meta-humor that often characterizes “South Park”, the episode does make fun of Muslim sensitivity to issues of Muhammad’s visual portrayal, even as it eschews portrayal itself. But then, to the best of my knowledge, there is no principle in Islamic law that forbids tweaking Muslims’ sensitivities. To collapse blasphemy against the Prophet with an offended collective sensibility, as revolutionmuslim.com does, is to confuse theology with contemporary politics. And to confuse theology with politics is, unfortunately, to play directly into the hands of the free speech fundamentalists.

Revolutionmuslim.com does not deserve our sympathy. The website’s claims to the contrary notwithstanding, there is no legitimate excuse for publishing the addresses of Parker and Stone or for the intimidation inherent in the image of Theo Van Gogh’s corpse. That said, the free speech fundamentalists’ own score card on questions of tolerance and understanding is hardly admirable, and their immediate indignation over al-Amrikee’s post provokes a productive question: What are the political and intellectual foreclosures inherent in valorizing free speech as an unassailable virtue (not merely a legal right) beyond all criticism?

In his April 25th piece, “Not Even in South Park?” , New York Times columnist Ross Douthat acts as an effective, if utterly unoriginal, mouthpiece of liberal free speech fundamentalism (although Douthat fashions himself as an intellectual conservative, his defense of free speech would surely please John Stuart Mill). Douthat seems most troubled by the fact that Islam has even succeeded in censoring “South Park”, that most impudent watch dog of American freedom of expression:

Across 14 on-air years, there’s no icon “South Park” hasn’t trampled, no vein of shock-comedy (sexual, scatalogical, blasphemous) it hasn’t mined…Except where Islam is concerned. There, the standards are established under threat of violence, and accepted out of a mix of self-preservation and self-loathing.

Of course, neither Douthat nor other free speech fundamentalists are under any obligation to sanction Muslim sensibilities about the Prophet Muhammad or criticisms of the “South Park” episode in particular. That said, Douthat’s apoplexy over the censorship of the corporate speech of Comedy Central seems off mark—after all, corporations frequently censor their statements for myriad reasons. More troublesome, however, is the eagerness with which Douthat dismisses Muslim sensibilities and criticisms without endeavoring to comprehend them in the least. A deep ignorance about Islam saturates his column. This fundamentalist dismissal of Muslim criticisms reveals a crisis and a contradiction in liberalism more generally: Free speech no longer coexists with the complementary and supplementary principle of free and rigorous inquiry. Without the balance of inquiry—the antithesis of self-satisfied ignorance—free speech quickly becomes a doctrinal fundamentalism like any other. And, more tragically in the case of Islam’s relationship to contemporary American society, the ignorant defense of free speech leads to a proliferation of fear.

Icon sold in Iran until the Danish cartoon controversy.

Molly Norris, a Seattle cartoonist who has emerged as one of the more interesting figures in the “South Park” controversy, is more forthright than Douthat about the role of fear in her own anti-Muslim provocation. As a response to Comedy Central’s decision to censor aspects of the second installment of the episode, Norris dedicated a facetious cartoon to Matt Stone and Trey Parker, titled “Everybody Draw Mohammed Day”. Soon after Morris’ cartoon appeared on the internet, an independent Facebook group took inspiration from it and proclaimed the upcoming May 20th “Everybody Draw Mohammed Day”—unfortunately, it is difficult not to suspect that this blasphemous faux holiday will only serve to reinforce broader American misunderstandings of Islam and Muslims. Norris explains her motivations for drawing the cartoon with the following illuminating remarks on her fear and ignorance of Islam:

I am personally afraid of Muslims because the peaceful folks of that religion do not often come forward to differentiate themselves from any radical elements! I mean, if I do not hear from moderate Muslims then how am I supposed to KNOW that they, too, are not harboring ill intent toward non-Muslims?! Please if you are a non-radical Muslim tell people about yourselves. Write to newspapers. Have community round tables. When Americans don’t know what you really think or feel, we might stay mired in stereotypes. Offer us knowledge!

Sadly, Norris’ twin fear and ignorance are both ridiculous and routine. In classic, patronizing liberal fashion, she places the responsibility for her fear and ignorance of Islam on Muslims themselves: “Offer us knowledge!” Are we really to believe that she has been deaf to the many Muslim individuals and organizations that have struggled to do just this over the past decade? Of course, given public fantasies of Islam in the United States, this attitude is hardly surprising; its typicality makes it all the more frustrating. To state the matter somewhat schematically: In contemporary liberal societies (both American and European), the defense of free speech is a means of reinforcing stereotypes and ignorance about Islam, rather than a means of combating them. This tragic, ironic reinforcement is all-too-evident in both Douthat’s indignation and Norris’ fear.

Last week, I had the pleasure of discussing the Jyllands-Posten controversy with a devout, African-American Sunni friend of mine here in New York. I asked him what his first response to the Danish caricatures was, and he responded with admirable nuance. His thoughts are equally applicable to the current South Park controversy, so I’ll leave the final word to him:

When I saw them, my first reaction was ‘Really? I mean, this is just silly.’ Think of all of the things that Muslims have been through over the centuries. Just look at the life of the Prophet, all of the challenges he faced. And you want to make a big deal over these stupid cartoons? Of course the cartoonists were out to offend us, of course it would’ve been better had they not published them. But the Muslims who reacted violently weren’t acting as good Muslims either. For someone who truly understands and follows the example of the Prophet, as every devout Muslim should, there are more important things to worry about than some ridiculous images.

My thanks to Adam H. Becker and Noah D. Salomon for their invaluable comments on this piece.

Jeremy Walton is an Assistant Professor and Faculty Fellow at the Religious Studies Program, New York University.

Update: This article was reposted at RevolutionMuslim.com.