Who Shall Live and Who Shall Die? An Unethical Ethics Committee Decides

A medical ethics expert reviews the film The God Committee

(A scene from The God Committee)

The 2021 film The God Committee should be riveting. The movie opens in 2014 when a soon-to-be recipient of a heart transplant dies and the intended heart is now available for someone else. Viewers learn that there is a state-wide waiting list with candidates in ranked order, but the heart has arrived at the hospital and the patient at the top of the list has died. Three possible recipients are in the hospital. None is a perfect recipient in a world – as this one is, as ours is – where there are not enough hearts to go around. Based on formulas designed to calculate the recipient’s long-term life expectancy post-transplant, none of the three would be at the top of the transplant list. One has a history of addiction, another lacks adequate insurance, and one has little family support. Under normal circumstances, one of the three would be disqualified outright, but he is, as we soon learn, the wealthiest. Given the urgency, one of them will get the heart or it will go to waste. The hospital transplant committee has only one hour to make a decision before the heart can no longer be used.

The committee responsible for making the difficult decision consists of five people: a hospital administrator, a priest, a psychiatrist, a transplant doctor, and a nurse. The transplant doctor, Jordan Taylor, is new, and thrown right into the deep end. She is replacing her (secret) lover and colleague, Andre Boxer, a senior superstar surgeon who is leaving for the private sector.

The film pivots between 2014 and a parallel situation seven years later, when Boxer himself needs a heart to live. He is also a less than ideal candidate. The ensuing real-time 2014 debate is filled with ethical conundrums: the youngest candidate is a drug addict, supposedly in recovery but likely relapsing. He should be excluded, but his wealthy father is a trustee of the hospital and has pledged a $25 million donation to save the faltering transplant program. The quid pro quo is clear, and, ethically, the committee should reject the offer. But $25 million would save several additional lives. The tension, such as it is, rests on whether the wealthy addict, Trip Granger, is truly in recovery, and to what extent the hospital administrator, Dr. Valerie Gilroy, is willing to lie to make sure he gets the heart so the hospital will get the money.

Such a dilemma, with only an hour to make a decision, is the stuff of great stories. It is also the stuff of great stage plays, as this, by Mark St. Germain’s, originally was. It’s the stuff – combined with a supremely talented cast including Julia Stiles, Kelsey Grammer, and Janeane Garafolo – of Oscar-worthy movies. But 2021’s The God Committee, directed by Austin Stark, disappoints despite the meaty issues of medical ethics it tackles: Why should one patient, Walter Curter, with less robust insurance be condemned to die? Why should patient Janet Pike die because she lacks family support? Will the rich really be able to buy their way out of this one? The movie is a glimpse into the difficult questions hospitals have to deal with every day, with unflinching honestly about the nature of profit-driven health care.

The film is also, honestly, kind of boring. Ponderous. It hits the viewer over the head with ethical questions without subtlety or nuance. That real-time decision is basically all there is. The characters are flat and one-dimensional; their relationships are peripheral; and when it comes to their secrets, despite Kelsey Grammer’s turn in playing a crotchety and ailing aging man, there is little reason for the audience to care about their lives.

While The God Committee is not a good film, in some basic workmanlike-ways, it is an informative one. As an expert on medical ethics, I would not recommend watching it to learn how transplant decisions actually get made. But it does highlight the complexities of these decisions. For example, it is not clear, even in this case, who the best candidate for the transplant is when there is only one heart. It is not even clear what constitutes “best.” Perhaps insurance should not matter, but given that the hospital needs money to function, it absolutely does. Perhaps counting lack of family support is punitive; it might also be pragmatic. Maybe being overweight is symptomatic of historically inaccessible health care and healthy food options outside the patient’s control. The film’s debates highlight the complex interplay between structural forces around access to resources, biological factors that influence the long-term success of transplants, medical factors that determine whether the patient will survive, and ethical factors about how to determine not only the best bet for the transplant but who deserves it most. There is no clear answer. And while the film highlights how the ethical choice might not be the pragmatic one, it also asks: if $25 million will save additional lives, is that not also a kind of ethical choice that deserves consideration?

While The God Committee is not a good film, in some basic workmanlike-ways, it is an informative one. As an expert on medical ethics, I would not recommend watching it to learn how transplant decisions actually get made. But it does highlight the complexities of these decisions. For example, it is not clear, even in this case, who the best candidate for the transplant is when there is only one heart. It is not even clear what constitutes “best.” Perhaps insurance should not matter, but given that the hospital needs money to function, it absolutely does. Perhaps counting lack of family support is punitive; it might also be pragmatic. Maybe being overweight is symptomatic of historically inaccessible health care and healthy food options outside the patient’s control. The film’s debates highlight the complex interplay between structural forces around access to resources, biological factors that influence the long-term success of transplants, medical factors that determine whether the patient will survive, and ethical factors about how to determine not only the best bet for the transplant but who deserves it most. There is no clear answer. And while the film highlights how the ethical choice might not be the pragmatic one, it also asks: if $25 million will save additional lives, is that not also a kind of ethical choice that deserves consideration?

In the real world, hospital committees rank their candidates for the transplant list with formulas and calculations to determine which recipients will have the best outcomes after the transplant. In stark terms, this means who will live the longest. Such metrics are biased toward younger patients, of course, but also toward those with fewer health challenges, more structural family support, better access to long-term healthcare, and fewer complicating health factors (like obesity, addiction, disability, and, as the pandemic has highlighted, chronic illness). These decisions often ignore why people might have additional health problems. While ideally, hospital committees ignore historical and structural issues that make some people less healthy and with less access to proper nutrition, sometimes decisions need to be made. And when ranking criteria are applied, disabled people rarely get prioritized. This has led, recently, to changes in these metrics, with life expectancy calculations looking at short-term rather than long-term outcomes. With a smaller set of expectations, people with shorter life expectancies because of disability and chronic illness are not immediately excluded from access to care.

The formulae are designed – rightly – to alleviate some of the impossible pressures on those making these decisions. The trauma for health care providers in making on-the-spot rationing decisions is immense, and we are only beginning to see these effects in places hardest hit by COVID triage. But these metrics not only punish disability, they fundamentally ignore what makes a life, and what makes a life valuable. The committee members, as we see in the film, are bound by their patients’ health metrics. But the committee members are also caregivers. They know these patients and care about them and advocate for them, because it is not only metrics that make a life. But in this film, and perhaps in life, the metrics and the money still matter most.

The God Committee does give viewers some brief details about each patient, but they are merely a highlight reel, with most attention to the rich one whose father will donate a massive amount of money that would save the faltering transplant program. But he is also an addict and maybe a terrible person. If this sounds like a litany of ableist, fatphobic, classist descriptors, it is. That’s kind of the point. That’s how these decisions are made. When there is not enough to go around, some kinds of bodies and people are prioritized over others. And time is of the essence. Emotion and relationships, the film argues, are only a distraction. We may wish for more advocacy and more engagement with what makes a life, but that only makes these necessary decisions harder.

It’s not only the patients who are shallowly drawn portraits in the film. In an unlikely and honestly rather silly pairing, Julia Stiles’ young and ambitious Dr. Jordan Taylor is having a secret affair (and eventual child) with Kelsey Grammer’s grouchy but idealistic transplant superstar Dr. Andre Boxer. Complications ensue and I’d tell you about them, but I mostly do not care and neither, I suspect, will you. This might be a deliberate move to emphasize that, much like with the transplant patients, inner lives do not contribute to the long-term metrics. And maybe that is right, but it also makes the film unnecessarily dull. And that is why it is also wrong; we do, in fact, need to care about people in order to advocate for them and to understand why they – why everyone – matters. And the film does make that point: In 2014, Dr. Taylor struggles with the committee’s relentless focus on metrics to decide who gets the heart. In 2021, when it is Boxer, her former lover, who needs a heart to save his life, Taylor again struggles with the metrics. Given Boxer’s condition, he will die in short order even with a new heart and would never qualify for a transplant. The only way to get one is illegal and unethical. Taylor goes that route anyway, not necessarily because of her love for him, but because of the transplant technology he’s developing, which could eliminate the need for donor hearts all together, saving untold numbers of lives. Such a breakthrough would also remove the pressure from these committees to play God.

In both cases – 2014 and 2021 – the film takes a strict utilitarian perspective: the heart should go to the person whose life will benefit the most people, the wealthy Trip Granger and surgeon-turned-inventor Andre Boxer, respectively. It is another way of saying hearts should go to the most deserving people, not because of their long-term life expectancy, but because of the lives that will be saved by saving theirs. It is a different way of measuring value. In Granger’s case this seems ethically bankrupt: he is, we learn, still using drugs. He is abusive. He is a bad person. By virtue of these restrictions, he absolutely does not qualify for the heart. His addiction will destroy the heart, and he will likely die soon after the transplant. It is a waste and will cost someone else the chance to live. But Gilroy, the hospital administrator, hides that evidence. And in so doing, she ensures that the hospital transplant program lives. How do we measure that question against the promised gift of twenty-five million dollars? That’s precisely the sort of temptation that the metrics are designed to guard against, and that’s precisely why Gilroy has to falsify records.

The Boxer example is designed to make us question the ease of our earlier convictions. Unlike Granger, whose value is measured in his father’s dollars, Boxer’s personal skill and merit – despite him also being a terrible man – is clear. It is because of who he is and what he can do and how many lives he could save that he, perhaps, deserves to live, even if only for a short time longer. But Boxer is an even worse transplant candidate than Granger; there is no way to falsify records, no possible cover-up within the system. So Taylor agrees to go outside the system and transplant a black market heart. She wants to save lives: Boxer’s and others. The financial backers in Boxer’s tech start-up company buy the heart; they probably just want to make money.

The legal and prevailing ethical framework of hospital transplant committees is that the money should not matter. The $25 million should not matter, even though insurance dollars very much do. But if, somehow, the committee can be convinced to know that the patient is not using, then he – young, rich, thin, (white), with a strong social and familial network and ample insurance support – is perhaps the perfect candidate in terms of those metrics. If he is not using, he will live the longest. So can the committee, in under an hour, find a way to believe, despite all evidence to the contrary, that he is in recovery? Or, really, can Gilroy provide enough plausible deniability to the rest of the committee to believe in his recovery? She personally doesn’t care. She believes the lives saved by the $25 million far outweigh the benefits of any of the other patients getting this heart, even if, in the addict, the heart is likely wasted.

(Image source: Caitlin Hillyard/KHN illustration; Getty Images)

That is not how decisions should be made. And, to be fair to ethics committees that exist across the country making decisions like these, it is truly not how they are made. There is usually more time and more information. There are formulae that determine both the quantity and quality of life expectancy, with the additional nuance of debates that can alter what the formulae predict. And today these formulae are, quite rightly, changing because of the advocacy of disabled and marginalized communities. But in a profit-driven health care system, questions of cost and insurance are always at stake. It may not be $25 million, but money always comes up.

There is a powerful question here: what is the cost of playing God? The film does not take this up. But it could. This is a question that matters, and it emerges from decisions that hospitals make every day.

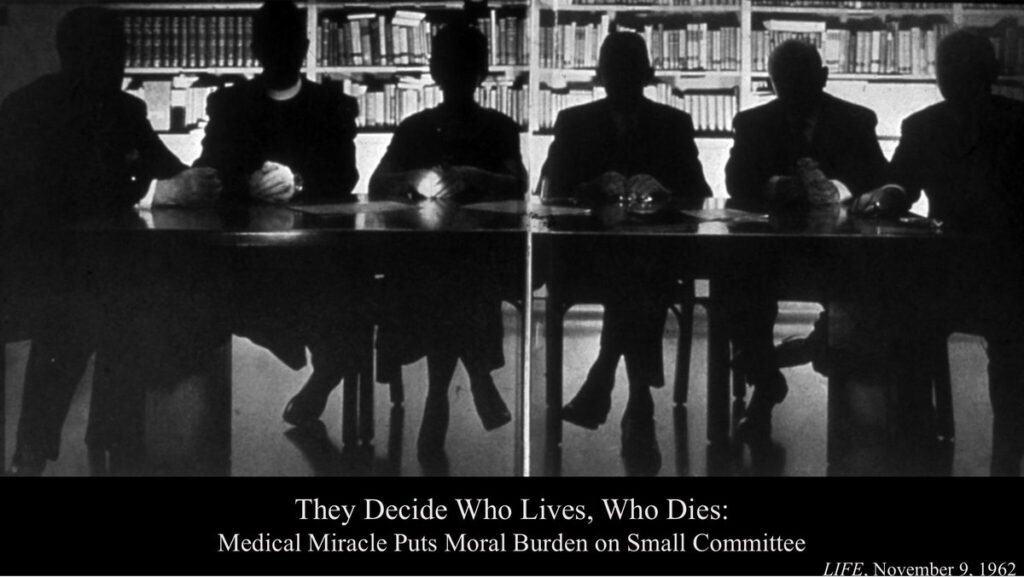

The God Committee mobilizes a powerful history of how modern clinical bioethics began. In 1961, the Seattle Artificial Kidney Center at Swedish Hospital established a seven-person committee to determine who should have access to the limited number of life-saving hemodialysis machines. The committee consisted of unpaid private citizens chosen by the King County Medical Society and included a lawyer, a minister, a banker, a housewife, a state government official, a labor leader, and a surgeon. The committee deliberated over each potential patient, following medical recommendations to exclude children and anyone over 45 but operating without any real guidelines. Designed to protect doctors from this terrible and awesome responsibility, the committee was, in many ways, playing God. Only later nicknamed “The God Committee,” the group’s work was chronicled in a 1962 article in Life magazine by Shana Alexander. Readers responded to the lack of clear framework by which the committee made decisions, particularly given the tremendous consequences to selection and exclusion. While more artificial kidney machines soon became available, making the work of the committee obsolete, the fundamental challenges of rationing remained, leading to the establishment of more robust bioethical criteria for practical allocation of scarce resources.

(Life magazine, 1962)

The film’s title is a nod to a key moment in bioethics and acknowledges that even with bioethical principles, criteria, and heuristics, decisions remain far from clear and open to debate. Committees are now comprised of people in the healthcare field who have received training in bioethics and rationing protocols. But they still have to make extremely difficult decisions with incredibly high stakes. People, even with guidelines and rules, are subject not only to avarice and competing motivations, but disparate moral codes.

The God Committee offers little critique and even fewer solutions for the main characters’ dubious ethical choices. It makes clear that buying a black market heart is concerning. It is not suggesting we sell or buy organs as a long-term solution. But, as the ethics of this film seem to suggest, anything might work in a pinch if the pinch is tight enough. It does not at all emphasize the problems with an organ market, and perhaps it sides with those who would support such an approach, ignoring the potential danger it poses to people who are already vulnerable.

A better, more feasible, and less dangerous solution for the scarcity of organs for transplant patients is for more people to become organ donors, to have an opt-out system rather than an opt-in system. But that is another topic this film does not address. I wish it spent more time on the costs of a healthcare system motivated by profit, and what the need to make money causes us to lose. And I wish it spent more time underscoring that everyone’s life is worthy of being saved, not because of the scale of the benefit their lives might bring, but simply because they are a life.

Sharrona Pearl is Associate Professor of Medical Ethics at Drexel University. Her most recent book is Face/On: Face Transplants and the Ethics of the Other. You can find clips of her freelance writing at www.sharronapearl.com.