Not So Sorry

What Makes an Apology Worthwhile?

Do apologies for clergy abuse offered by the Catholic church and Southern Baptist Convention do anything to instill trust?

(Image by Riccardo Antimani)

Ten years into his papacy, Pope Francis has delivered a lot of apologies for clergy abuse. Most recently, during his trip to Portugal for World Youth Day in August, Francis met with survivors of abuse on his first day in the country. Earlier this year, a panel looking into the Portuguese church’s history of abuse found that more than 4,800 children may have been abused by Catholic clergy between 1950 and today. So the pope traveled to Portugal to apologize once again. But are the pope’s apologies actually good apologies? And what makes an apology worthwhile in the face of something as grim as clergy abuse?

As has repeatedly been the case elsewhere, the church hierarchy in Portugal downplayed and hid its abuse issues for decades. The church has paid a price for this, both literally in the form of payments to abuse victims, and figuratively in terms of the shrinking number of Catholics. Like many other European countries, Portugal has seen a decline in the number of practicing Catholics in the past few decades, and its abuse inquiry may exacerbate that decline.

After an hour-long meeting with victims, the pope said that “it is often accentuated by the disappointment and anger with which some people view the church, at times due to our poor witness and the scandals that have marred her face and call us to a humble and ongoing purification.” While the pope has repeatedly acknowledged the anger and suffering of abuse victims, there’s a lack of specificity in this statement about what actions the church will take in Portugal. Bishop José Ornelas, the head of the Portuguese Bishops Conference, said in February of this year that abuse “is an open wound which pains and embarrasses us.” It’s true that both the pope and Ornelas’ statements acknowledge that victims have suffered and that the church has done wrong. But is acknowledgment really an apology?

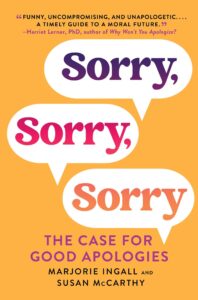

In January of this year, Marjorie Ingall and Susan McCarthy published a book called Sorry, Sorry, Sorry: The Case for Good Apologies. The authors, who run a website tracking bad public apologies called SorryWatch.com, drew on psychology, sociology and law to come up with a six step process toward what they define as a good or worthwhile apology. The steps they offer include using the word “sorry” in your apology, being specific about what you’re apologizing for, showing you understand why it was bad, not making excuses, saying why it won’t happen again, and making reparations. If we apply this formula to most apologies for clergy abuse, we might get as far as number 1, after which many churches skip to #6 and offer a payment in order to move the problem along. Or, as has lately happened with increasing frequency, church dioceses declare bankruptcy to avoid paying reparations.

In January of this year, Marjorie Ingall and Susan McCarthy published a book called Sorry, Sorry, Sorry: The Case for Good Apologies. The authors, who run a website tracking bad public apologies called SorryWatch.com, drew on psychology, sociology and law to come up with a six step process toward what they define as a good or worthwhile apology. The steps they offer include using the word “sorry” in your apology, being specific about what you’re apologizing for, showing you understand why it was bad, not making excuses, saying why it won’t happen again, and making reparations. If we apply this formula to most apologies for clergy abuse, we might get as far as number 1, after which many churches skip to #6 and offer a payment in order to move the problem along. Or, as has lately happened with increasing frequency, church dioceses declare bankruptcy to avoid paying reparations.

This is why many victims of clergy abuse cannot and should not offer forgiveness. An insincere, weak, or poorly formulated apology followed by an offer of money that is meant to essentially get them to go away does not facilitate any kind of psychological or spiritual healing, but instead sweeps the problem under the rug, and doesn’t guarantee the same thing won’t happen again in the future. The Greater Good Center at U.C. Berkeley explains that, in their research on forgiveness, one key element of a meaningful apology is explaining why an offense happened, “especially to convey that it was not intentional.” But when it comes to clergy abuse, the problem is that it is almost always intentional. No person in power abuses someone else by mistake.

***

After revelations of abuse in the Southern Baptist Convention rocked America’s largest evangelical denomination, leaders of the church gathered in Anaheim, CA in 2022 to draft a series of reforms to try and prevent future abuse. Pastor Griffin Gullege said that in many cases, rather than apologizing, Baptist pastors who abused congregants and church staff would only admit to a “moral failing” before resigning, thus avoiding any consequences. The “resolution of lament and repentance” they drafted ultimately read, in part, that the SBC leadership:

“publicly apologize to and ask forgiveness from survivors of sexual abuse for our failure to care well for survivors, for our failure to hold perpetrators of sexual abuse adequately accountable in our churches and institutions, for our institutional responses which have prioritized the reputation of our institutions over protection and justice for survivors, and for the unspeakable harm this failure has caused to survivors through both our action and inaction.”

Unlike many of the apologies offered by the Catholic church, this statement at least admitted wrongdoing and did not offer excuses. But it never gave any specific next steps, nor did it explain why this abuse, the scale of which is still being investigated, was allowed to go on for so long. The scale of the abuse cover ups led to Russell Moore, one of the denomination’s most prominent public figures, to resign in disgust, and to refer to the abuse as apocalyptic for Southern Baptists.

In failing to be specific about next steps, the apology gave the SBC loopholes to return abusive pastors to the pulpit. Just a few months after it was issued, former SBC president Johnny Hunt, who was named as an abuser in the investigation, was cleared by the denomination to return to pastoral work.

***

Why are so many clergy apologies hollow and meaningless? The answer is connected to the concept of clericalism, which in the Catholic church has repeatedly been linked to the history of abuse. The Association of U.S. Catholic Priests issued a whitepaper in 2019 unpacking what clericalism means. Essentially, clericalism upholds the idea that clergy are special or above the laity to the degree that they aren’t questioned, or that they become so isolated that it can enable abuse. But this has dire consequences for both clergy and laypeople. For clergy, it can lead to narcissism, which in turn allows them to feel they can get away with, for example, spending thousands of dollars of parishioner’s donations on travel, remodeling rectories, or in the case of one bishop, providing cash gifts to Vatican higher ups.

Clericalism can also allow clergy to feel they can abuse people and not need to apologize for it. In some cases, parents tell children to “never question a priest,” which sounds like a red flag to many of us, but is a behavior that still persists today in many churches. In the Catholic church, the shrinking number of seminarians means young priests can have their egos inflated by leadership and laity alike, which too can lead to their feeling that they don’t owe anyone apologies.

This isn’t just a Catholic church problem. The Secrets of Hillsong documentary, which aired earlier this summer, revealed that Fred Houston, who founded the evangelical megachurch in Australia in 1983, and Brian Houston, his son who helped grow the church into an international evangelical powerhouse, may have both sexually abused women. Brian Houston is currently being charged with covering up his father’s abuse. But this was somewhat overshadowed by the downfall of Hillsong’s “hypepriest,” American pastor Carl Lentz, known for his tattoos, pricey sneakers, and friendships with celebrities from Justin Bieber to Kanye West. Lentz, who participated in the documentary, is being accused of sexual abuse by at least two women, accusations he claims are “categorically false.” Because of the scandal, Lentz was fired from Hillsong in 2020.

The apologies offered by both Lentz and Brian Houston are vague, and once again allow both men the loopholes they need if they someday want to return to ministry. In the documentary, Lentz says “I let down, genuinely, a lot of good people, and I can only apologize and change.” But how he will change and what that means in the case of the women and staff members he’s accused of abusing remains unclear. In terms of Brian Houston, who resigned from the church in 2022, Hillsong issued an apology the same year in which they stated that “we apologize unreservedly to the people affected by Pastor Brian’s actions and commit to being available for any further assistance we can provide.” In both cases, it’s unclear what, exactly, these two former pastors are going to do, and even more unclear what Hillsong will do.

Watching the Hillsong documentary, it’s easy to play armchair psychologist and see that both Houston and Lentz display characteristics of narcissism, which includes a grandiose sense of self-importance along with a lack of empathy and a tendency to use other people to the narcissist’s advantage. That same description might be applied to any number of Catholic or Southern Baptist Convention clergy who were abusers as well. And it’s likely that a narcissist cannot issue a meaningful apology because, given their ego inflation, they cannot see they have done anything wrong. Denial, excuses, and deflection are easier than owning up to abuse, explaining why it happened, and offering reparations.

Because abuse is so often about power, clergy abusers find it challenging to offer a good apology. Because apologizing means humbling yourself, it also means voluntarily letting go of the power you hold over other people. Clericalism doesn’t allow this to happen. But the exodus of believers from the Catholic church, the Southern Baptist Convention, and megachurches led by abusers like Hillsong, along with a series of shallow apologies may be enough to humble their leadership. That doesn’t guarantee their apologies will get any better. But at least more people will be aware they are owed one, and the more a meaningful apology is demanded, the more one might someday be offered.

Kaya Oakes is the author of five books, most recently including The Defiant Middle: How Women Claim Life’s In Betweens to Remake the World. She teaches writing at the University of California, Berkeley.