Vodou Fashion and Faith

An excerpt from Vodou En Vogue: Fashioning Black Divinities in Haiti and the United States

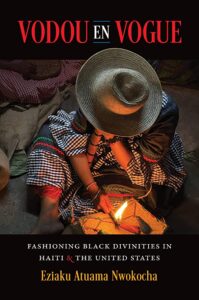

(Manbo Vante’m Pa Fyem smiles as she participates in a Vodou ceremony. Image source: Eziaku Atuama Nwokocha)

The following excerpt comes from Vodou En Vogue: Fashioning Black Divinities in Haiti and the United States by Eziaku Atuama Nwokocha. Copyright © 2023 by Eziaku Atuama Nwokocha and used by permission of the University of North Carolina Press.

The excerpt addresses the Vodou warrior goddess Ezili Dantò, the Vodou priestess Manbo Maude, and Maude’s child Vante’m Pa Fyem.

***

Ezili Dantò chose Vante’m Pa Fyem. When Manbo Maude became pregnant with her, she was already overwhelmed with the effort of raising two other children. The strain on her finances was so great she considered seeking an abortion to spare herself and her family the burden. That same night, as though summoned by Manbo Maude’s instinct to terminate the pregnancy, Dantò came to her nan dòmi. The spirit told her to keep the baby. Manbo Maude expressed her worries: she was exhausted, and another baby would further drain her depleted resources. Dantò was insistent. The child belongs to her, the deity said; the child was special. You need to keep her. I will provide for you. Manbo Maude was never one to refuse the will of the spirits, not when they reached out so purposefully. If Dantò’s words were true, her child was favored by the divine. Since that night, Manbo Maude says she never again suffered dire financial difficulties. Dantò kept her word.

Ezili Dantò’s history in Vodou is closely tied to the Haitian Revolution. Stories tell of a gruesome mutilation performed to ensure she would keep confidences: her tongue was cut out of her mouth, either by Black people who wanted to ensure she would never share the secrets of revolutionaries with enemies or by White people who wanted to hobble the massive rebellion. Centuries after the Revolution’s end, she is still incapable of speaking: her recognizable k kk kkkk kkkk sounds are only decipherable by practitioners through the aid of translators who follow her around the ceremony. In legend, Dantò has a cherished daughter named Anais who acts as her mouthpiece to the world, speaking the words her mother can no longer articulate. In ceremonies, the practitioners who keep close to Dantò, conveying her messages, play the role of her divine daughter. The story of a celestial daughter speaking for her mother resonates in the earthly realm of Manbo Maude’s temples, where Vante’m Pa Fyem often communicates Manbo Maude’s words and needs to others. Vante’m Pa Fyem frequently acts as one of the translators when Manbo Maude and others are mounted by Dantò, verbalizing whatever messages the deity is miming toward practitioners and audience members. She becomes Dantò’s mouthpiece.

Vodou en Vogue is my own attempt at translation—not of the words of a singular deity or Manbo but of the intricacies of the public ceremonies I witnessed and the stories I was told. Concluding with a neat statement seems ill-fitting for a book filled with stories about a Black woman as innovative as Manbo Maude and spirits as varied and dynamic as the Vodou pantheon. They are too lively to be captured fully within the confines of any conclusion. Instead, I offer a few dènye panse, Haitian Kreyòl for “last thoughts,” that articulate not only the knowledge my work has produced but also a sense of the inescapable shifts within Vodou itself. Vodou changes over time, just as all religions do; its practitioners and rituals cannot be held in stasis. Traditions are passed down through spiritual lineages, and with each successive transition they shift, accommodating new places, people, and experiences. Thus, these last thoughts cannot represent a definitive end for Manbo Maude or her communities, just a snapshot of where they are in a particular moment and the foreshadows of where they might go from here.

Vodou en Vogue is my own attempt at translation—not of the words of a singular deity or Manbo but of the intricacies of the public ceremonies I witnessed and the stories I was told. Concluding with a neat statement seems ill-fitting for a book filled with stories about a Black woman as innovative as Manbo Maude and spirits as varied and dynamic as the Vodou pantheon. They are too lively to be captured fully within the confines of any conclusion. Instead, I offer a few dènye panse, Haitian Kreyòl for “last thoughts,” that articulate not only the knowledge my work has produced but also a sense of the inescapable shifts within Vodou itself. Vodou changes over time, just as all religions do; its practitioners and rituals cannot be held in stasis. Traditions are passed down through spiritual lineages, and with each successive transition they shift, accommodating new places, people, and experiences. Thus, these last thoughts cannot represent a definitive end for Manbo Maude or her communities, just a snapshot of where they are in a particular moment and the foreshadows of where they might go from here.

Throughout Vodou en Vogue, I emphasize the interplay between the spirits, practitioners, and audience, offering a new interpretation of the relationality within African Diasporic religions through the concept of spiritual vogue. It pulls together multiple influences—materiality, religion, race, queerness, sensation, and performance—that are arguably individually inherent to African Diasporic ceremonies yet together offer fascinating insights into the relationship between the people and spirits that bring life and meaning to religion. I make plain that the fashion showcased during Vodou ceremonies is indicative of an interactive process, the meaning of which is only evident through considering the practitioners, spirits, and audience as dependent on one another for successful ritual work. Material culture strengthens the beliefs of devotees and facilitates communication with the gods, a cyclical exchange that satisfies the spirits and guides practitioners. In addition to revealing the negotiations between deities and their devotees, spiritual vogue also underscores the practicalities of ceremonies, the friction caused by the intersection of faith and everyday social, economic, and cultural mores. Vodou ceremonies are animated by performance rituals that, through the lens of fashion, reveal fissures within the religious community, generating complex portraits of gendered possession practices, sexual intimacy with the divine, faith labor, and racial, sexual, and gender identities.

The concept of spiritual vogue, as well as the entirety of Vodou en Vogue, is rooted in the notion that religious fashion cannot be dismissed as a mere manifestation of conspicuous consumption. A simplistic dismissal of the material culture in Vodou and other African and African Diasporic religions misses vast cosmological traditions anchored in the everyday practices of lived religions and would ignore crucial conduits to the gods. The anecdotes, interviews, and theories I explore throughout this book clearly show the centrality of transnational material culture to Black practitioners’ ability to forge intimate and spiritually meaningful connections with the divine and with one another.

At the beginning of my research, that nexus between performance and fashion, alongside the valuable insights drawn from queer Black and Brown people in Ballroom culture, brought me to spiritual vogue. The communal systems shaping expressions of race, sexuality, and gender in Ballroom also appear within the structure of Vodou ceremonies, where performance rituals convey normative beliefs around gender, sexuality, and sex while simultaneously creating ruptures in those same perceptions. Spiritual vogue is not dependent on public-facing ceremonies—those are simply the religious events I had access to as a non-initiated researcher. The lack of insider access, far from restricting my work, narrowed my focus to the core intricacies of ceremonial spaces, directing my attention to the crucial connection between practitioners, spirits, and the audience. Instead of chasing the secrets of the initiated, I sought the overlooked knowledge on display in crowded temples, full of practitioners ready to speak with the spirits and one another. The triangulation of practitioners, spirits, and the audience is also applicable to more private affairs that still involve performance rituals carried out in front of witnesses within a religious community: certainly, the concept expands beyond Vodou into other African and African Diasporic religions such as Ifá, Candomblé, and Santería. At its center, the concept describes the ritualized performance of identity and piety in front of an audience, an idea that is expansive enough to elucidate the role of sensation and material culture in many religious traditions beyond Haitian Vodou.

(Manbo Maude. Image source: IMDB)

For more than a decade I attended Vodou ceremonies, in and outside Manbo Maude’s homes, building relationships with devotees and learning the purpose and practices of performance rituals. Focusing on Manbo Maude and her temples led me to the idea that the gods speak to their devotees through avenues they can understand, making room for the talents practitioners can then incorporate into their religious practices. Manbo Maude’s devotion shows in every seam, trim, and ruffle she dons during ceremonies. Her garments are evidence of her ability to communicate with the divine and a material tool through which she facilitates continued connection to the spirits for herself and other practitioners. The role of fashion in her religious practices is so foundational she has built it into the structure of her ceremonies, introducing stops and starts to showcase spiritually inspired outfits. My observations, theories, and conclusions are grounded within the communities that were generous enough to let me step into their temples.

Throughout Vodou en Vogue, I think largely within Black participants’ own words and descriptions, allowing my work to follow wherever their practices and stories led. Inevitably, the time I spent in Manbo Maude’s temples led me, again and again, to her youngest daughter Vante’m Pa Fyem. Of Manbo Maude’s three children, all of whom are initiated, Vante’m Pa Fyem is the most integrated into the workings of the temples. Her spiritual authority and her wealth of knowledge are rooted in her connection to Manbo Maude, a relationship that is often reinforced during ceremonies through their intentionally similar outfits. Tellingly, these clothes are similar, not identical. In part, this is a result of Manbo Maude’s more powerful position within the temples. Yet it also reflects the fact that Vante’m Pa Fyem is in the process of cultivating her own opinions on Vodou, fashion, religious ritual, and community that are influenced not only by her mother’s lifelong tutelage but also by her personal experiences as a young woman in the Haitian Dyaspora. She is an increasingly knowledgeable Manbo in her own right, learning from her mother while developing her personal understanding of how to serve the spirits. Her burgeoning opinions, potentially deviating from Manbo Maude’s, are indicative of Vodou’s essential capacity to change over time.

Vante’m Pa Fyem’s ability to innovate reflects the core characteristic that drew me to Manbo Maude’s temples at the start of my research. Manbo Maude’s homes caught my attention and held it, compelled by the distinctive use of fashion and how those expressions of material culture underline truths about African Diasporic religious practices and spiritual connection far beyond the thresholds of the temples in Jacmel and Mattapan. Manbo Maude, as individual as she and her communities are in their particulars, is indicative of concepts, principles, and trends that are occurring nearly everywhere Vodou is practiced. Sustaining both her temples for more than twenty years has given performance rituals the time to grow and evolve, reflecting changes within her life, her relationship with the divine, and the many people who seek meaning through her ceremonies. Spiritual garments are the physical manifestation of those changes, archiving Manbo Maude’s shifting perceptions on the proper way to serve the lwa: they are also one of the primary elements that have kept her temples alive for two decades. Vante’m Pa Fyem is also key to their survival and will be even more so in the future.

Manbo Maude chose Vante’m Pa Fyem to inherit her temples, yet the knowledge she is transferring to her daughter is not reserved solely for her biological descendants. All her ti feỳ, the initiates and practitioners who seek her guidance, are part of her legacy, perpetuating the traditions she passed down from her own spiritual mother, to whom Manbo Maude was not biologically related. Every time she designs a spiritual garment and dresses up with her practitioners in front of an audience, she both offers her beliefs about how to serve the spirits and facilitates communication with them. Manbo Maude preserves and articulates the foundations of Vodou through her religious practices while also innovating by embracing her creativity and the will of the spirits, crafting material items in conversation with the divine. Visual and material culture—the physical manifestations of the traditions being passed from one generation of practitioners to another—is integral to the propagation of religious belief. Vante’m Pa Fyem, in addition to playing a key role in the operation of Manbo Maude’s temples, is representative of the broader transference of knowledge, continuing her mother’s legacy. The fashion they share is one manifestation of their connection and is an essential part of how Manbo Maude is attempting to construct her legacy. That legacy has consequences not only for Vante’m Pa Fyem’s future but also for the people in Jacmel who rely on the funds generated by spiritual work, the Black practitioners and audience members searching for a genuine link to their African or Haitian heritage, and for the practice of Vodou. The spiritual children Manbo Maude trains may one day come to develop their own performance rituals, creating new traditions that bear the mark of her influence.

Vodou’s history as an oral tradition can give rise to the erroneous impression that it is a religion without structure, especially when it is simplified within binaries between written and oral customs. Comparing Vodou to the formally institutionalized hierarchy of the Catholic Church, for instance, distracts from the fact that the faith has rules, some of which are described in this book. Even when rituals and gods vary across region in Haiti, the same underlying standards and concepts hold everywhere, proving both the resilience and the organizing principles of the traditions disseminated through generations. At the same time, Vodou changes and adapts to the needs of its practitioners. The passing along of knowledge inevitably leads to change. Manbo Maude, for example, learned to perform rituals and serve the spirits from her spiritual mother, while also developing her personal ideas about the importance of style within those traditions. Her spiritual mother provided her with the structure of her religion, but once she was imbued with spiritual authority, she experimented, building her capacity to communicate with the divine on her own terms. Vante’m Pa Fyem and Manbo Maude’s other ti feỳ are set to trek that same path.

Eziaku Atuama Nwokocha is an assistant professor of religion at the University of Miami.

***

Interested in more on this topic? Check out episode 35 of the Revealer podcast: “Vodou, Gender Variance, and Black Politics Today.”