Value for Our Shareholders: Reading the Islamic State Media

Why does ISIS produce newsletters that resemble corporate reports?

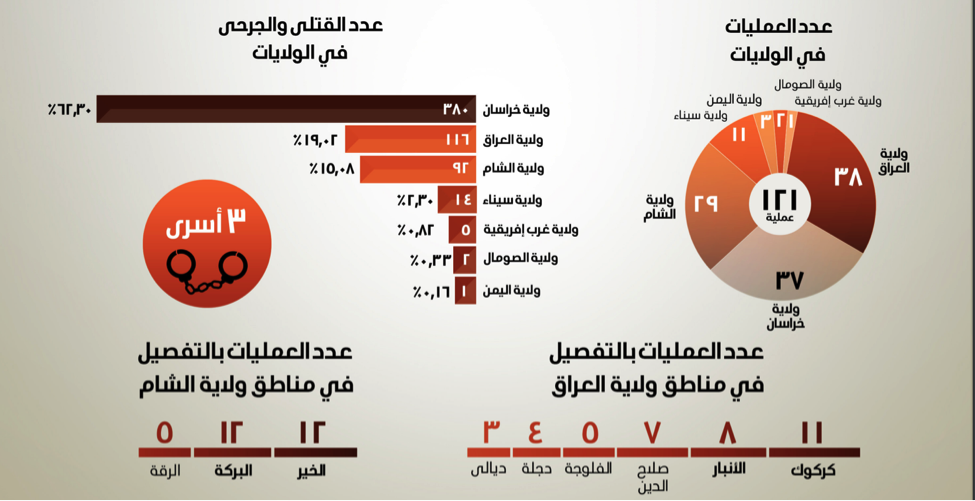

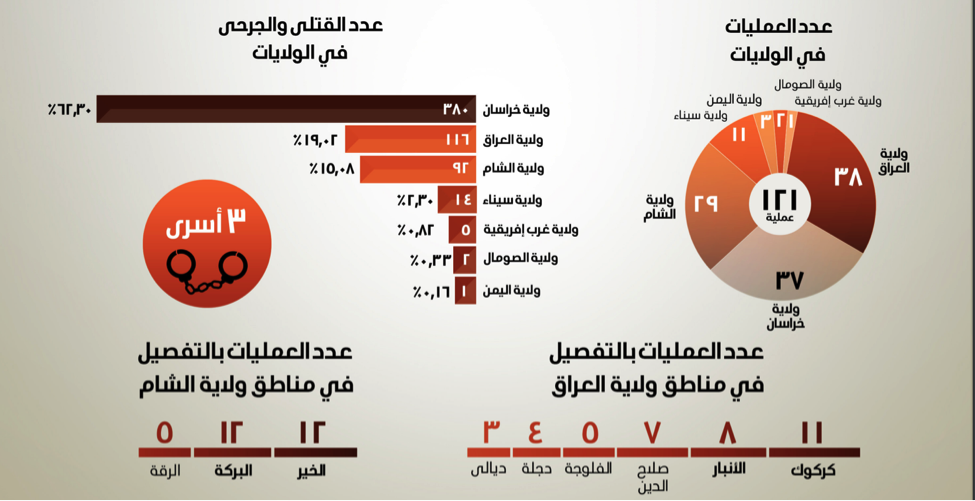

Source: al-Naba’ No. 153

Pie charts are probably not the first thing that come to mind when you think of the Islamic State (IS), variously known as ISIS (Islamic State of Iraq and Syria), ISIL (Islamic State in the Levant), or Daesh (a transliteration of the acronym formed from the group’s Arabic name, al-Dawla al-Islamiyya fil ‘Iraq wa ash-Sham, which ironically can also be an insult). Since surging onto the world stage in 2014, the militant group has become synonymous with gore in its varied forms, from videos of beheading prisoners to photos of mutilated corpses. Yet the group also churns out a different type of content, one that bears an uncanny resemblance to the type of fare you might take in with your morning coffee. Take al-Naba’, the group’s Arabic-language newsletter: part news bulletin, part corporate report, al-Naba’ recounts the military operations IS operatives undertook during the prior week, details how many enemies of varying stripes were killed or injured, and celebrates the spoils of war. The reader can quickly absorb much of this information by consulting charts and graphs that present different data points on a single page – an executive summary, if you will.

Reading al-Naba’ generates a different set of questions than those usually posed concerning the Islamic State’s operations and its media. To start with, what kind of religious fanatics feel compelled to issue progress reports? How should we account for its macabre data vis-à-vis its field operations? And what does the easy, almost seamless, adoption of the corporate reporting genre suggest about the place of this so-called “medieval” Islamic State in the modern world?

***

For years, political commentators have insisted that the Islamic State represents an errant holdover from a less civilized past. This is a narrative that has taken root Right, Left, and Center – perhaps most memorably illustrated in Graeme Wood’s influential article from The Atlantic, in which he lamented the “well-intentioned but dishonest campaign to deny the Islamic State’s medieval religious nature.” The slightly more nuanced version is that, in the words of former Australian Prime Minister Tony Abbott, the Islamic State exemplifies “medieval barbarism, perpetrated and spread with the most modern of technology.” This take has become Gospel among many security analysts, who tend to regard the group’s media as the pragmatic use of modern means to secure 7th century ends.

Many seem to want the Islamic State to belong to another world — be it the medieval one or the Islamic one — the important thing is establishing maximum distance between “their” world and the one “we” inhabit. Yet no serious analysis can support this comforting myth. Even the Islamic State’s theology, dependent as it is on the 11th/12th century scholar Ibn Taymiyya, advances novel remixes of older concepts, from takfir (excommunication) to al-wala’ wal bara’ (loyalty and disavowal) and even Khilafah (the Caliphate). Rather than deploying modern means for medieval ends, the Islamic State is marked by that most modern of traits: the tendency to mistake means for ends, the inability to articulate an end other than one of destruction. In an age in which there appears no alternative to the prevailing political and economic order, we should not be surprised to find that the Apocalypse appears to be a viable option.

Let us unpack the argument by taking a closer look at al-Naba’, which has been distributed through a number of online platforms, from Telegram to Hoop and TamTam. Lacking many of the design features that the group’s English-language glossies (Dabiq and Rumiyah) were known for, al-Naba’ is more school newspaper than Vanity Fair. Yet the newsletter has proved the most enduring title within the IS media empire, publishing more or less continually since October 2015. Headlines are formulaic and create a blissfully context-free sense of accomplishment: “Caliphate soldiers kill 6 American soldiers in Khurasan” (No. 50). Or: “43 members of Shiite crowd killed in a failed raid on the village of Bashir” (No. 26). Against the background of the Islamic State’s defeat in Iraq and Syria, al-Naba’ still manages to find something “uplifting” to feature, often from its regional affiliates elsewhere, such as “30 apostates hit and killed from army of Niger” (No. 173). Not even the death of Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi caused a departure from this general formula. At the level of affect, this format conveys a sense of perpetual action: here, finally, Muslims are doing something – taking action instead of merely lamenting their woes.

Recounting tales of the vanquished foe is of course an old literary trope, but we would be wrong to attribute the Islamic State’s approach to this ancient convention. The Hebrew Bible, Chronicles II, for instance, reports the killing of 500,000 men from the Kingdom of Israel in the midst of the civil war with their rivals in Judah. It is noteworthy that such figures are both exaggerated and completely imprecise. They serve as a stylistic tool, not an attempt to convey facts. And therein lies the difference between the Islamic State’s modern death accounting and the ancient trope they purportedly copy and extend: IS aims to inform, to communicate data with accuracy and precision, attending to details in a way which would have been completely foreign to their ancient counterparts. While the writers of al-Naba’ deploy several stock phrases and lean on linguistic ambiguity to amplify success—adversaries often are “killed and wounded” without specifying how many fall into which category—their accounts are by no means fictitious. Even the body counts are mostly accurate. For example, after the 2015 attacks in Paris, the lead story boasted that “more than 500 crusaders” were killed or wounded (No. 6), as compared to 130 killed and over 400 injured.

Roughly translated into English as “the announcement,” al-Naba’ is also the name of several TV stations in Arabic-speaking countries, further gesturing to mainstream mimicry. Al-Naba’ hews closely to the conventions of contemporary journalism with stories that cover the standard Five W angles of reporting: What type of assault was it? Where did the attack happen? Who carried it out, and how was it all coordinated? As we have seen from alt-right publications closer to home, the point is not to explode the genre but master it. Perhaps tellingly, the “why” never assumes a place of prominence in these stories – an absence we can either attribute to its obviousness or to the fact that such questions have simply ceased to matter.

The adoption of this communication style is reflective of broader trends that are so pervasive in our market-based world that we must stop ourselves from taking them for granted. The Islamic State feels compelled to analyze its missions, report on its activities, and justify itself through its results. We would have a hard time finding medieval Muslims thinking or speaking about jihad in such terms, which should further undermine any tendency to approach this history as an unbroken chain linking the 7th century to the present. On the contrary, time and again we find that while contemporary jihad fails to resemble its earlier iterations, it does mirror the world we live in now.

Take, for example, the following charts. The graph on the left represents the number of people killed and wounded in different IS provinces, while the pie chart on the right indicates the number of operations undertaken in each place as a percentage of the Caliphate’s total activities. The figures at the bottom provide further detail about attacks carried out in Iraq and Syria.

Source: al-Naba’ No. 153

Later issues of al-Naba’ introduced a regular feature called “Harvest of the Soldiers,” which details the number and type of adversaries killed or wounded and the military equipment captured or destroyed. The following example comes from No. 206, the first issue published after the death of Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi. It notes that more than 179 opponents were killed or wounded in 71 campaigns that week, including “116 infidels and apostates” and “15 crusaders,” among whose ranks were five officers and commanders. Again, the focus on precision is noteworthy. Even in the face of minimal material progress, the Islamic State will have you know it is not slacking on its record-keeping.

Source: al-Naba’ No. 206

Military campaigns are not the only focus of these newsletters. They also spotlight the Islamic State’s varied media productions. The following newsletter details the activities of the Islamic State’s two primary media groups, al-Hayat and al-Furqan, boasts of the magazine issues, anāshīd (religious chants), and notes that its media is operating in eight different languages.

Source: al-Naba’ No. 6

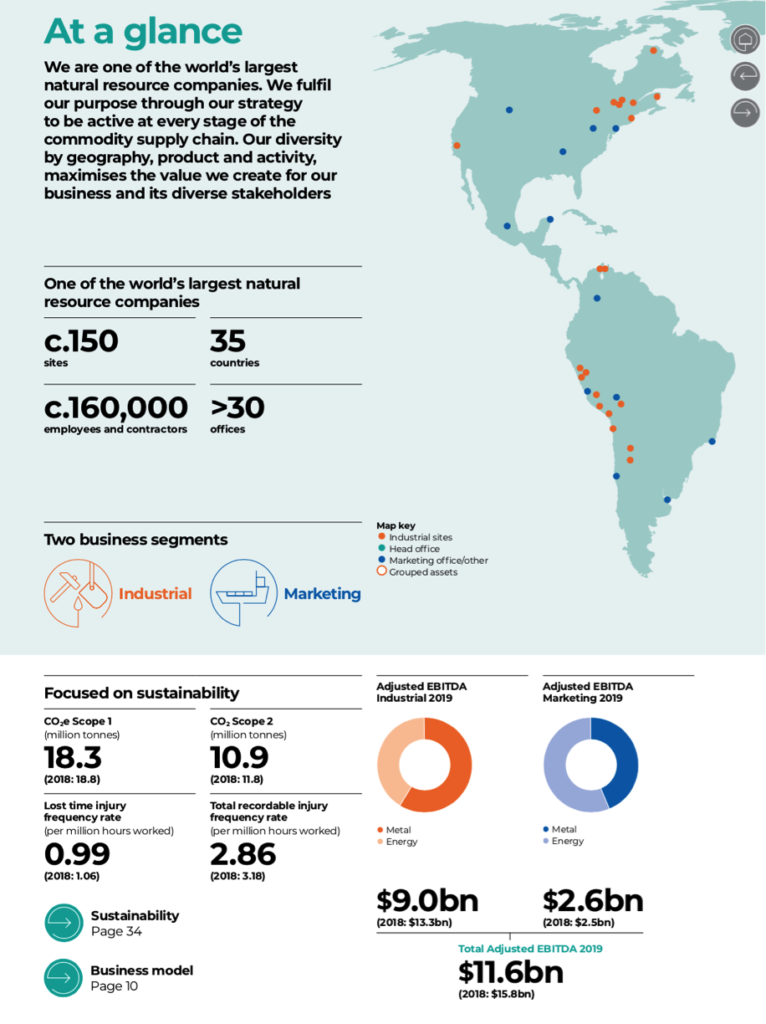

Again, we would search the records from pre-modern Muslim conquerors in vain for anything that resembles this reporting style. On the other hand, al-Naba’ seems right at home alongside the periodic updates issued by corporations, NGOs, and government agencies: “This year we held X events, produced Y publications, served Z participants, in Q cities.” For comparison’s sake, take the following summary page from Glencore’s 2019 annual report. One of the world’s largest natural resources extraction firms, Glencore boasts of the global scope of its operations and reports its earnings in graphical formats that are easy-to-access.

This is not an argument about equivalences between radically different organizations, but an observation about how the tendency to justify oneself through recourse to “the results” is pervasive, even in the most reactionary quarters. In a world obsessed with statistics and outcomes, such reports serve as a key communications strategy for organizations seeking to validate their existence by utilizing market thinking. We must all account for our activities, and the Islamic State is keeping up with the times.

What, then, are the markers of success that al-Naba’ reports? How does it measure organizational performance? Here the essential nihilism of the Islamic State comes into clear focus. For anyone concerned with human dignity, there is something unsettling about surveying death via pie chart. The reduction of human lives to data points brings to mind some of the darkest moments of the last century, and in particular, the meticulous accounting of totalitarian states. But even they could argue to be advancing some greater aim in this world: cue Stalin’s infamous quip that one death is a tragedy while a million deaths is a statistic. But the Islamic State is not, nor will it ever be, the Soviet Union.

The reality is that a functioning Caliphate, one that replaces secular political models with divine sovereignty, remains an elusive goal. Still al-Naba’ strives to conveys a sense of purpose and action, gesturing toward a fixation on means that is shaded by the absence of ends. Indeed, it is noteworthy how little attention al-Naba’ pays to situating varied attacks in a larger strategic context. It is frenetic activity for its own sake, because destruction—and its propagandistic use as spectacle—is all there is to hope for now. Of course, the death and destruction recounted in these newsletters are not figments of the imagination, and each headline represents human suffering. But to borrow from my colleague (and frequent Revealer contributor) Patrick Blanchfield speaking of American gun culture, it is human suffering not as sacrifice but as waste.

***

For years researchers have noted the disproportionally high number of engineers within Islamic militant groups including al-Qaeda, Lashkar e-Taiba, and Hezbollah. Closer to the media front, we might recall Ahmed Abousamra, the Boston-born computer scientist who edited the Islamic State’s English-language magazine, Dabiq. For sociologists Diego Gambetta and Stephen Hertog, the presence of such recruits among the jihadist groups stems from their supposed “need for cognitive closure” – i.e. the demand for clear answers to complex questions (we might wonder, as a bitter aside, whether the relatively few history and literature majors among the jihadist ranks might forestall the oft-mentioned “death” of the humanities).

I believe there is a slightly different angle that we could take on this data. Today’s jihadist organizations hold special appeal for those who have been trained to think in instrumental terms – and why not, given what we have seen of al-Naba’? There are numbers to be crunched, data to be mapped, casualties to be counted, and so much to do. Far from being anti-modern or even selectively modern—i.e. using the tricks and tools of the present to advance a 7th century agenda—the Islamic State is steeped in the calculative mode of thinking we all take for granted. Far from being pre-modern, much less medieval, it represents the continued triumph of instrumental reason in our hypermodern present, offering a 21st century spin on Hannah Arendt’s observation that “businessmen became politicians and were acclaimed as statesmen, while statesmen were taken seriously only if they talked the language of successful businessmen.” But to what end? And how do the chosen means correspond with its actualization? Here the narrative starts to falter, not merely for the Islamic State but for us as well. That our means seem increasingly without ends, or are rather confused with them, should no longer serve as a surprise.

***

In the book of Exodus, God tells Moses that when taking a census of the Israelites, each shall give a coin that will be counted in his stead. Various commentators have taken this detail to indicate that there is something indecent about counting human beings as one might number livestock. Reducing individuals to figures represents a trespass on human dignity, flattening the whole of individual existence into a data point. Similarly, in his Groundwork for the Metaphysics of Morals, Immanuel Kant argued that one articulation of the categorical imperative would be to “act that you use humanity, whether in your own person or in the person of any other, always at the same time as an end, never merely as a means.” Yet we fail to live up to this directive all the time. The world built by capital and shaped by the need to manage populations is a world of facts and figures. To regard human beings as ends in themselves, whether from a religious or Kantian framework, is to find oneself at ethical odds with the normative social order where information must be collected, measured, and above all put to profitable use.

Yet our abundance of data — the thousands killed by guns each year, the millions who lack health insurance, the percentage of our population projected to die of Covid-19 — does not necessarily bring us any closer to eradicating gun violence, enacting universal healthcare, or finding a cure for the novel coronavirus. We might note that we too tend to confuse data with progress, mere calculation with human flourishing. Far from offering an alternative viewpoint, the “medieval” Islamic State enables us to see in high relief what problems might be lurking in the world we hold in common.

Suzanne Schneider is Deputy Director and Core Faculty at the Brooklyn Institute for Social Research, focusing on history and political theory. She is the author of Mandatory Separation: Religion, Education, and Mass Politics in Palestine. Her new book about contemporary jihad, The Apocalypse and the End of History, will be released by Verso Books in 2021.