Using Comedy to Talk about Religious Trauma

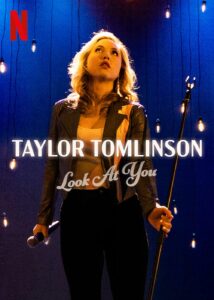

A review of Taylor Tomlinson’s Netflix special Look At You

(Photo by Netflix and illustration by The Daily Beast)

“I grew up with God; he’s a douchebag, all right,” joked Taylor Tomlinson in her 2022 Netflix comedy special Look At You. “Did he tell you you were broken and you need him? That’s his move, that’s what he does. He says that to everybody. Don’t drink what he gives you. You drink that, next thing you know, you’re eating his body, the holy spirit’s inside you, it’s a whole system they have over at that frat house they call church. Who else uses Roman numerals?”

The 28-year-old comedian, raised in a devout Christian household, frequently calls out Christianity in her comedy, including in her earlier Netflix special Quarter-Life Crisis. But in Look At You, Tomlinson becomes one of the first female comedians to talk about living in conservative Christian communities where mental illness and female sexuality are stigmatized. This conflict shaped her outlook on life and her work on stage.

As opposed to comedic routines about sex and religion written by men, like Dana Carvey dressing up as a prudish Church Lady on Saturday Night Live, or John Mulaney cracking jokes about Catholic sexual guilt, Tomlinson finds success talking about religion and sex from a female point of view.

Tomlinson grew up in a religious community where Christianity touched every part of her life, often in damaging ways. Her comedy is a powerful tool for other religious trauma survivors, serving as a platform to introduce their experiences into the mainstream and to help them separate harmful beliefs from where they learned and internalized them.

Tomlinson says she first felt religion’s impact in her childhood. “I did not grow up in a household that was very mental health-conscious,” Tomlinson explains, “we were very religious.” Although a recent study shows that the vast majority of American adults agree that having a mental health disorder is nothing to be ashamed of, Tomlinson shares how this is not often the case in conservative religious spaces. In Christian communities like the one in which she was raised, people view mental illness as a sign of weakness, shame, or a defunct faith, founded on the belief that a person can “pray away” their mental health problems.

When Tomlinson was in high school and asked her dad about the panic attacks she was having, he gave her advice that made her feel like a werewolf. “All I can tell you,” she says mimicking her father’s low, raspy tone, “is that when you feel like this, get as far away from the people you care about as possible until you feel different.” As Tomlinson understood it, “just run into the woods ‘til you’re not a monster anymore.”

In addition to suffering from panic attacks, Tomlinson also has bipolar disorder. It was “a tough pill to swallow,” she laughed about receiving the diagnosis, “and I’ve swallowed a lot of pills.”

(Image: Tomlinson on stage for her Look at You tour)

“Being bipolar is like not knowing how to swim,” she says. “It might be embarrassing to tell people, and it might be hard to take you certain places, but they have arm floaties,” by which she means medication. “And if you just take your arm floaties, you can go wherever the hell you want.” Tomlinson uses the metaphor of needing arm floaties, and of drowning, to convey the danger behind the joke. When religious communities like hers stigmatize mental illness and provide no legitimate resources for people to get help, the threat of suicide and self-harm is frighteningly real.

Her story highlights how she wasn’t able to get help in her childhood home, in part because of her family’s religion. It’s hard to imagine if you live outside these systems, but Tomlinson didn’t have her parents’ support to seek out professional help, and even if she did, she lived in a community where people condemned anyone who turned to mental health services or who took medication for mental illness.

As someone who grew up in a similar religious environment, this was the first time I heard someone talk about the idea that mental illness is a struggle you fight alone, a struggle between you and God. Her comedy struck me because it speaks to how people live with the reverberations of these teachings, and the ensuing religious trauma, for years.

Tomlinson is also one of the first comedians I’ve encountered who explores issues of sexuality and conservative Christianity. “I’ve never seen a vagina, not even my own. I’m a Christian,” Tomlinson tartly remarks as she shifts to talk about her sexual experiences and purity culture.

Purity culture refers to a movement, especially popular among – although not limited to – white evangelical Christians, that tries to convince young people to remain abstinent until marriage. Adolescents, particularly young women, are taught that if they have sex or sexual thoughts before marriage, they not only disappoint God and their families, but that they are tarnished, used, and no longer pure. The movement reinforces traditional, binary gender roles and heterosexual attraction as God’s intended plan for everyone.

Tomlinson regales her audience with stories of youth groups where she learned, “it’s not the physical act of masturbating that’s the sin you guys, alright. It’s not even the orgasm. In fact, if you have a wet dream, thank God for the freebie and have an awesome day,” she kneels to kid eye-level and fist-bumps the air like a camp counselor. “But what are you thinking about while you’re doing that to yourself guys? That’s what the sin is. It’s the lust in your heart. It’s the impure thoughts in your head.”

Like many who grew up in communities that promoted purity culture, Tomlinson has suffered long-term consequences. “It gave me some serious trust issues,” she says. “And it just made me weird, growing up in church, in ways that I am still discovering. For example, I just found out that I masturbate wrong,” by which she means that years later she still believed she had to clear her mind when she wanted to be intimate with herself. “When I got to be an adult, and I wanted to masturbate, I was like, well, if I just don’t think about anything, I could probably still go to heaven, right? Just like clear your mind, get in there, get it done, see you soon Jesus, right?”

Tomlinson talks openly about her initial hesitancy to explore her own body through a funny anecdote about experiencing her first orgasm with her college boyfriend. “‘You’ve been here for 19 years, you never went poking around on your own?’”, she pauses to mimic a realtor—a stand-in for her college boyfriend—leading her on a tour of her own downstairs. “I did once, but I thought Jesus would get mad. I don’t actually own this place, I’m just renting it from the guy upstairs. If I flood the basement, I do not get my security deposit back.”

What Tomlinson is talking about—feeling guilty about intimately knowing her own body—may seem outlandish: how or why would anyone believe or buy into these things? For those who were raised within the walls of these systems, it feels incredibly real. Central to purity culture is the idea that women do not control their sexuality. Men are in charge of women’s sexual experiences, reinforcing male ownership of female bodies. Tomlinson’s comedy reminds those of us who were once part of these communities, that it was real, and that others felt it too.

From the perspective of someone raised in these systems, her comedy is like hearing a Christian pop band cover your favorite church hymn. It feels familiar but not quite the same, because in that moment when you first hear it on Spotify you recognize that this song, like the lessons you learned, has power based on where you hear it. Outside of church, a space where these beliefs are unquestionable, they don’t have the same ring. On a comedy stage where nothing is sacred and nothing untouchable, Tomlinson upends beliefs I’ve only heard discussed in religious spaces, destabilizing their power by separating them from their context.

Often, we’re told that speaking something into existence gives it power, but it can sometimes do quite the opposite, as Tomlinson’s new special shows. Making religious trauma relatable through stories about werewolves, arm floaties, and masturbation helps her broader audience who was not raised in conservative Christian communities come closer to fostering empathy for the people they love who have lived through these things.

One of her most successful bits recalls the time her friend first learned that her parents weren’t divorced, but that her mom had actually died of cancer when she was eight. “Taylor, you told me your parents were separated,” Tomlinson recalls her friend saying. “And I was like, ‘Well, they were! By Jesus.’” Clearly, Tomlinson has found ways to use humor to help her make sense of religious teachings for many years. And now, she says about her mom, “she’s in Heaven, I’m on Netflix, it all worked out.”

Before she had Netflix specials, Tomlinson used comedy as a copying mechanism. “My parents don’t have a dark sense of humor, but I do,” Tomlinson explains, “and I’m glad I do because if you can laugh at the darkest stuff that’s ever happened to you while it’s still actively happening to you, sometimes that’s what gets you through it.” This perspective is part of what empowers her to talk about difficult topics, including conservative Christianity’s role in current U.S. politics.

Before she had Netflix specials, Tomlinson used comedy as a copying mechanism. “My parents don’t have a dark sense of humor, but I do,” Tomlinson explains, “and I’m glad I do because if you can laugh at the darkest stuff that’s ever happened to you while it’s still actively happening to you, sometimes that’s what gets you through it.” This perspective is part of what empowers her to talk about difficult topics, including conservative Christianity’s role in current U.S. politics.

“I don’t see God revamping His old shit, and let’s be honest,” Tomlinson jokes, “He probably should because the people who own it now suck.” Amid growing political power of the Christian Right surrounding reproductive rights and access to comprehensive healthcare, Tomlinson’s comedy sheds light on how the fight for bodily autonomy among conservative Christian communities is a deep-rooted issue years in the making. As her stories about purity culture demonstrate, conservative Christians aren’t going to stop with overturning Roe v. Wade; they want a Christian heteronormative nation.

Tomlinson’s comedy is meant to make her audience uncomfortable, but in a way that allows conservative religious experiences to feel funny. Her comedy also provides a space for fellow survivors of religious trauma to consider triggering experiences from a new angle, showing how their experiences are shared with countless others. Ultimately, she shows that religion is a lens through which she has lived her life, but not one that defines it – an incredibly freeing perspective for religious trauma survivors, and one that can foster empathy among those trying to understand their experiences.

Emma Cieslik is a freelance writer and museum professional based in Washington D.C.