Unsovereign Love: Thoughts on Race, Sex, and Undoing an Evangelical Education of Feeling

Reflections on a popular story about a Black, ex-lesbian convert to Evangelical Christianity

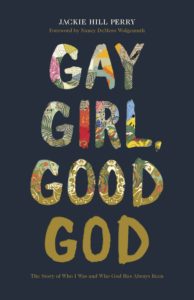

During the summer of 2018, a social media frenzy pulled me into a story that felt both extremely familiar — intimate, even — and also terribly alienating. The Christianity Today article at the center of the spectacle was entitled “I Loved My Girlfriend — but God Loved Me More.” Written by a rising star in the evangelical world, Jackie Hill Perry, the article is an excerpt from her memoir Gay Girl, Good God, that tells the story of how she, a black woman, was once a lesbian but then came to Christ and is now married to a man with whom she has started a family. What felt familiar to me in Perry’s story was how she went about interpreting her history in order to make the story of her conversion coherent. It is a procedure that I, too, learned from my own evangelical education in how to properly perceive God’s work in the world and shape one’s desires around that order. This is how it goes:

During the summer of 2018, a social media frenzy pulled me into a story that felt both extremely familiar — intimate, even — and also terribly alienating. The Christianity Today article at the center of the spectacle was entitled “I Loved My Girlfriend — but God Loved Me More.” Written by a rising star in the evangelical world, Jackie Hill Perry, the article is an excerpt from her memoir Gay Girl, Good God, that tells the story of how she, a black woman, was once a lesbian but then came to Christ and is now married to a man with whom she has started a family. What felt familiar to me in Perry’s story was how she went about interpreting her history in order to make the story of her conversion coherent. It is a procedure that I, too, learned from my own evangelical education in how to properly perceive God’s work in the world and shape one’s desires around that order. This is how it goes:

You begin by situating your story in a larger story. There’s creation, fall, redemption. Your creation story is a location. A way of situating yourself in a particular place, grounding the narrative arc.

Perry’s story follows this Christian formula. She’s a girl on the playground. She’s young. The attraction she has to women is longstanding. The force of those feelings is made visceral; they have the appearance of nature. She has a fleshly affinity to these desires, this label: lesbian.

But the natural world is not all there is. There is one who is above nature, who governs her story and gives her a new way to narrate herself. So, she renounces the natural, its force, its appetite and carnality — in short, its fleshliness — in the name of that supernatural and sovereign God who reveals the sinfulness of this nature.

The force of conversion to this divinely ordered perception of the world is total. It is not the transformation of a part, but the whole. The story need not be pretty — indeed, the messier it appears, the more authentic the conversion it announces. What is non-negotiable, however, is the direction toward which it is oriented. Perry gives her entire self over. Where once fleshly feelings for women ruled her identity, now it is ruled by Christ. Her body is a living sacrifice. She works to make it holy and acceptable to God. This is the power of God. Through her conversion, Perry comes to see how her history and human history are governed by God. In the same way that a political sovereign rules over their domain, God’s rule over all of creation gives God the sovereign authority to invade a mind enslaved to sin and set it free. She embraces the renunciation of the flesh in the name of the Spirit who joins her together in a new family, gives her a new name, provides her with a new meaning to her life. This is the story of redemption.

***

There is not just one narrative in Perry’s story, just as there is not one meaning. While initially I was more intent on ignoring Perry’s story than challenging it, in scrolling to the end of the article my eye was caught by its final bookend: Perry’s portrait photo and the tags the editors of Christianity Today had used to index the article. Taken as a whole, framing the excerpt, the tags give tell to the common sense — the shared feelings — of the larger story within which they were situating Perry’s story: “African Americans, conversion, homosexuality.” Beginning the excerpt with an author photo and concluding it with these tags generates more meaning for her story. They provide one final set of implicit directions telling the reader how to read and think about her. How to situate the information she’s selected for sharing within a larger evangelical imagination. With and without her consent, Perry is woven into a theological story that is bigger than her. A story of white theology and its claims to authority.

There is not just one narrative in Perry’s story, just as there is not one meaning. While initially I was more intent on ignoring Perry’s story than challenging it, in scrolling to the end of the article my eye was caught by its final bookend: Perry’s portrait photo and the tags the editors of Christianity Today had used to index the article. Taken as a whole, framing the excerpt, the tags give tell to the common sense — the shared feelings — of the larger story within which they were situating Perry’s story: “African Americans, conversion, homosexuality.” Beginning the excerpt with an author photo and concluding it with these tags generates more meaning for her story. They provide one final set of implicit directions telling the reader how to read and think about her. How to situate the information she’s selected for sharing within a larger evangelical imagination. With and without her consent, Perry is woven into a theological story that is bigger than her. A story of white theology and its claims to authority.

The layers of discernment, authorship, editing, arrangement, and selection that governed the choice of this essay for publication are rendered invisible. The selection of this excerpt about her life serves to provide a narrative arc for the whole story given in Gay Girl, Good God.

The blurb on the back jacket of the book follows up on the excerpt’s invitation. Readers are meant to imagine Perry’s story with her and learn to make sense of their fallen flesh together: Read in order to understand. Read in order to hope. Or read in order, like Jackie, to be made new.

Reading in order is the key here. Without this sense of order, the story — its understanding, hope, and novelty — begins to break down. Like the tags and photo that bracket the Christianity Today excerpt, the blurb implies the proper direction in which to read Perry’s story. For it is only by reading the world in the proper order that one can perceive God’s governance of everything. Joined with Perry, readers journey to new feelings and understanding so that their desires can be shaped and, in turn, legitimated by this story. Reading with her, we are made analogous to Perry. Made new in this story. Together, we renounce the fleshly feelings of homosexuality and become straightened out, corrected, redeemed. It is only by reading in order that the meaning of our existence is secured against any threats.

This evangelical education in feeling depends on training one’s senses around the story of a sovereign God who requires a sacrifice in order to bring salvation. Perry’s sexual conversion is both an invitation and an instruction. She is teaching us how to properly read her flesh within this evangelical imagination. She makes this story real, enfleshes it with her hands and heart, and so it is real. Her story is an education in feeling, in the senses. Her common sense, her sense-perception, her sentiments are a form of knowing. What does she know? That God has extracted her from the sinful situation of enslavement to her flesh.

From slavery to freedom. From lesbian to straight. There is something familiar about the narrative power that drives her story. Perhaps this is why “African Americans, conversion, homosexuality” are tagged in this essay. Perhaps the conversion of the flesh is the link between God’s management of salvation and Christianity’s management of race and sexuality. Convert the flesh, black flesh, black lesbian flesh, into something to be overcome. Generate meaning from its marks, situate it within a larger story of God’s authority and rule that justifies the overcoming of the flesh. This is a romance, a reconciliation of race and sexuality in the straightness given by God. Reading the story of Perry’s black, once lesbian, now straight flesh, we too can be reconciled, united, married. We can find understanding. Hope. We can be made new.

Jackie Hill Perry

Perry situates herself within the story of a Good God whose authority comes to her, a Gay Girl, “not in a church, or through contact with Christians.” Instead, “God broke in and turned [her] heart toward Him right in [her] own bedroom in light of His gospel.” God’s divine authorization of this break-in apparently occurs without mediation by another. Yet Africans arrived in America precisely because black people were written into the Christian gospel as heathens in need of conversion. The fact of the matter is that God is able to break into her bedroom because European Christians tore into black flesh first.

In the inscription of her black flesh into a Christian world, Perry is not an excerpt or an exception. Her blackness, and the symbolic weight of slavery that it still carries, testifies to a Christian sense of flesh in need of conversion. From slavery to freedom, can this divine guidance of history and human lives justify even captivity in the name of freedom? For in a theological view that says that God is in control of everything that happens, slavery is just a hiccup on the way to redemption. An unfortunate sacrifice of black flesh that will resolve into something higher.

But maybe the violence justified by God’s sovereign governance of history has nothing to do with the story Perry is telling. Maybe her story isn’t about race. Still, the reading in order, the tags “African Americans, conversion, homosexuality” — her black flesh — leaves a trace of the racial transformations at the heart of evangelicalism.

***

One problem with sovereignty is that it is incommensurable with love. Mastery, governance, and rule are antithetical to the freedom that love enables. In our patriarchal society, the narrative of a lover breaking into one’s heart or room is meant to sound romantic, but such a story, in the absence of consent, is about trauma. Sovereignty, the renunciation of disorder in the name of control, is the ruination of love. But the evangelical education of feeling depends on reading God’s governance as supremely good regardless of what it justifies. This is the tautology that gives Perry’s story its ground. Displace it and what remains? Perhaps the flesh of Perry’s ex-girlfriend remains as an open question. A question she attempts to close with a sovereignty that would justify the renunciation of the flesh, a conversion. A disavowal.

Writing herself into this divinely arranged story does not require forgetting the flesh. Instead, remembering the flesh in order to repeatedly sacrifice it is what secures the order of this story. These mini crucifixions require a regular renunciation: surveil yourself, root out the vestiges of sin, the traces of desire, straighten yourself out. The readers are not meant to question how this interrogation of self might be an education in self-harm, in doing violence to one’s own flesh.

***

Perry’s renunciation of her lesbianism pivots on trading her fleshly identity as a lesbian for a Godly identity as a daughter of the ruler of all of creation. But perhaps this exchange is where the story falls apart. Perhaps lesbian is not an identity, or the hinge for making a story open, but a practice of questioning. Questioning the stories of desire that appear natural, that exert sovereign control over the flesh. Perhaps “lesbian” names a way of questioning the attempt to exhaust the meaning of my flesh, or another’s. And perhaps it is the attempt to become responsible for loving the flesh rather than renouncing it. To become responsible enough to name one’s desire, communicate it honestly, and hopefully find consenting flesh that wants to touch, be touched, feel the force of the flesh pressed into it. If only for a moment. That impression may not be lasting or significant. Or it just might change a life.

To confront the force of the flesh without recourse to a story of God’s, or an individual’s, sovereignty is not to disavow God. To confront the finitude of one’s own flesh demands reimagining God’s love in terms ungoverned by the justifications and harm that fleshly renunciation provides. Without sacrifice, surveillance, and straightness. To love the flesh is to renounce a God who breaks into our hearts and bedrooms, forcing Himself and his conversion on us. It is, instead, to embrace the force that is felt in the blackness of existence and the opacity of the flesh, God’s and ours. It is to stand in the face of a mystery and feel the unsovereign demand of love. Dark, lovely, flesh.

Amaryah Shaye Armstrong is Assistant Professor of Race in American Religion and Culture at Virginia Tech. Her work brings together black feminist theory and black theology to examine the relationship between race, reproduction, and religion in the aftermath of the Middle Passage. She also co-hosts the ASSEMBLY podcast on the Political Theology Network and makes music at amaryahshaye.bandcamp.com.