Totem and Tattoo: Is forgiveness an act of the will or of the body?

Conversations about forgiveness are empty debate unless we talk about the body.

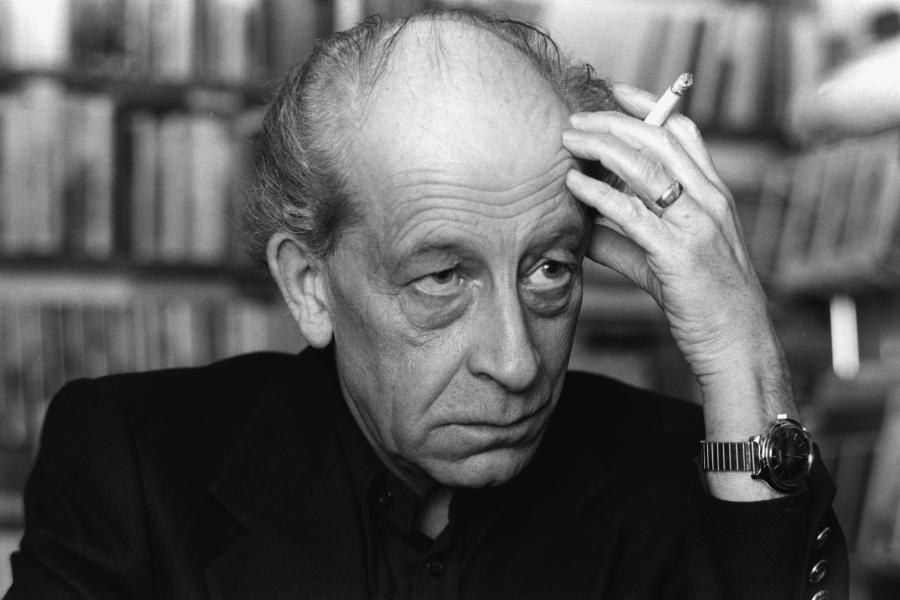

Jean Améry

“Every morning when I get up,” the essayist and philosopher Jean Améry wrote, “I can read the Auschwitz number on my forearm, something that touches the deepest and most closely intertwined roots of my existence; indeed I am not even sure if this is not my entire existence. Then I feel approximately as I did back then when I got a taste of the first blow from a policeman’s fist. Every day anew I lose my trust in the world.”

I have been rereading this passage—and Améry’s oeuvre as a whole, really—throughout the winter. These months have felt like a momentary lull in the endless stream of stories about famous men apologizing, or failing to apologize, or failing to apologize while apologizing.

In the last eighteen months a whole new genre of commentary has sprung up, analyzing all the ways famous men have botched their apologies.

There is Louis C.K.’s claim that it had never occurred to him that women in his profession might feel coerced when he asked to masturbate in front of them, which—if true—is so staggeringly oblivious that it might be worse than actual malice.

There is Dustin Hoffman’s insistence that he never even met the seventeen-year old girl he propositioned on the set of The Death of a Salesman (1985) with the quip that he’d have for breakfast “a hard-boiled egg … and a soft-boiled clitoris.” This, despite copies of letters she had sent to her sister at the time and a photograph of Hoffman with his arm draped around her.

Then there is Harvey Weinstein’s deranged, madcap ending to his apology, where he joked that he was going to channel his rage into the NRA. “I hope Wayne LaPierre will enjoy his retirement party. I’m going to do it at the same place I had my Bar Mitzvah.”

Mario Batali’s achingly stupid cinnamon bun recipe.

And on. And on. And on.

These apologies are the best documents we have to understand what it is like to be a powerful man who feels sexually entitled to anyone in his orbit. And it is not hard to sympathize with the impulse to tear apart these apologies and accuse their authors of insincerity or self-absorption or callous indifference to the women harmed.

It’s satisfying to read articles disemboweling these apologies because they are loathsome, these famous men, with their flippancy, their insouciance, their non-sequiturs that we are supposed to find cute. But in our single-minded focus on how the apologies have failed, we have allowed the experiences of the people receiving the apologies to recede out of sight. The whole problem has become one of finding the right words to say, not whether the injured party can or should accept the apology at all. The question of when we might refuse to forgive disappears altogether.

And that is where Améry comes in.

For there simply is no conversation about the refusal to forgive without Jean Améry. His essay “Resentments” is the single best piece of writing on the topic, and sooner or later anyone who thinks seriously about forgiveness has to deal with it.

He is never self-aggrandizing, nor is he prone to oversimplifications. He does not lay claim to heroism or virtue by dint of having suffered. Even in moments of self-pity he views his own weakness almost as scornfully as he views Germany’s forgetfulness about its recent past. Rather, he is an autodidact who binds his own memories together with philosophical reflections using wonderfully economical, balanced sentences, that hit like a mace crumpling a skull. He writes about the refusal to forgive as an act of time, ethics, and collective guilt. There is plenty for me, as a scholar of religion, to say about the coherence of his ethics or the theological lineage of his language.[1] But the most interesting question he poses in passages like the one cited above, is often overlooked: “What is the role of the body in forgiveness?” It is a question religious studies, with its emphasis on ritual and cultivation of the self through habits, is particularly well-suited to address.

Améry wrote “Resentments” in the 1960s, just as the tacitly agreed upon silence surrounding the Holocaust was beginning to break. The piece starts out with a description of a trip through the countryside of a green and immaculate land. Everywhere he travels, he meets an “impressive combination of cosmopolitan modernity and wistful historical consciousness,” and he freely acknowledges that “the working man” thrives there. Gradually, though, a sense of unease stains his description of the landscape and Améry admits the real purpose of his essay. The land is Germany, he is an Auschwitz survivor, and his aim is to “speak as a victim and examine my resentments”—“No amusing enterprise, either for the reader or me,” he drily acknowledges.

Few people writing about forgiveness have had as much to resent as Améry.

He grew up in Austria, the son of a Jewish soldier killed in WWI and a Catholic mother. His upbringing had the cultural trappings of Christianity, complete with Christmas trees and carols, but was still considered Jewish enough by neighbors that he was taunted on the playground. His actual education was in a Realschule, a trade-oriented school, rather than the more intellectual Gymnasium, but Améry consistently hid that fact in later life, claiming to be university educated.

He was only twenty-three when Germany ratified the Nuremberg Laws, which would define much of his early life. Married to a Jewish woman against his mother’s wishes, he fled after the Anschluss, first to France, and then later to Belgium, with his young wife next to him and an old Jewish man in overlarge rubber shoes clinging to his belt, groaning and promising him “all the riches of the world if only I allowed him to hold on to me now.”

Once in Belgium, he joined the Resistance, papering the city at night with anti-Hitler leaflets. He describes his arrest, when it finally happened in 1943, as something between a noir film and a slapstick comedy. After the Gestapo came in and put Améry in handcuffs, the officer tersely ordered him away from the window, growling that he knew the trick prisoners played, where they wrenched open the window with their chained hands and fled on to the ledge. “I was certainly flattered that he credited me with so much determination and dexterity,” Améry wryly observed, “but, obeying the order, I politely gestured that it did not come into question. I gave him to understand that I had neither the physical prerequisites nor at all the intention to escape my fate in such an adventurous way.”

Torture followed arrest, and Auschwitz followed torture. Without any technical or medical skills, Améry was assigned to the most brutal, unskilled labor. He was transferred to Bergen-Belsen, freed when the war ended, and then spent the next two decades working as a journalist for a popular press. Only in 1964, after the Holocaust had finally entered public conversation in the wake of Adolf Eichmann’s trial, did Améry begin to write about his time in the camps.

Améry’s work is sometimes framed as literature about trauma, most notably by W.G. Sebald in The Natural History of Destruction, but Améry himself rejects that diagnosis in his essays. At various moments in his writing he skewers the whole idea that his psychology could be reduced to a pathology or syndrome, insisting that the real pathology lies with the society that pretends nothing happened.

Instead, he argues that his resentment stems from the irreversibility of time. The natural direction of both time and society, Améry argues, is toward the soft dulling of forgetfulness. He, however, is pinned to the truth of the conflict, unable to forget what happened and “nailed to the cross of his ruined past.” It may be absurd, it may be a fruitless revolt against the past, but the victim holds the moral truth of the conflict.

The body is everywhere in Améry’s account of his life and continuing resentments, from his description of his arms twisting as he is strung up in torture, to his morning ritual of reading his tattoo, years after escaping Auschwitz.

Scholarly literature does have plenty to say about forgiveness and the body—at least, a certain understanding of the body.[2] Want lower blood pressure? There’s a 2005 study linking lower blood pressure to forgiveness. Tired of feeling run down and sick? According to a 2001 study, forgiveness will boost your immune system. Cardiovascular health need a boost? Forgiveness can potentially offer that too through lower levels of cortisol, a 2011 study suggests. Depressed? Definitely try forgiveness, recommends one 2006 study. Afraid of the reaper? A survey of three separate studies tentatively concludes that your aging body can prompt reflection, leading to increased reflection, spirituality, and reconciliation with the past, potentially leading to improved health outcomes. Worried that your refusal to forgive makes you neurotic and disagreeable? Actually, you’re fine. The same 2011 study that linked lower cortisol levels to forgiveness tried and failed to find a correlation between a victim’s “levels of neuroticism and agreeableness” and “cortisol and forgiveness.” But remember, you’re on notice—someone got scientific funding to research whether you refused to move on because you’re just so unpleasant.

All of these studies are about the body and forgiveness, but they are based on a particular understanding of the body as a unit that can be measured and assessed for different health outcomes. It’s not that I want to write off such work as unsophisticated. There is actually an incredibly lively discussion about what constitutes forgiveness buried in these efforts to assess the impact of forgiveness on health.

Researchers are trying to pull apart the disposition to forgive (“forgivingness”) from the act of forgiving in a particular situation. They want to know if we refuse to forgive because certain wrongs are so egregious that we cannot or will not forgive them, or if we are the type of people who dislike forgiving. Other studies that attempt to isolate the positive health benefits of actively forgiving an offender (in the sense of condoning or reconciling with) from the improvements that come from reducing stress, resentment, and negative affects associated with holding a grudge. There are debates over whether forgiveness produces emotional changes in the forgiver, or proceeds from emotional changes toward the offender. All of these are worthwhile conversations, but they all share the same blindness: they only understand forgiveness as acting upon the body, not the body as acting upon forgiveness.

Jean Améry

This is because these pieces lack an understanding of the body as a site for habits—that is, of Améry’s body. When I talk about habits, I am not talking about the automatic way I stumble out of bed in the morning to find my coffee. Rather, I am drawing on the whole ethical-psychological tradition — stretching from Aristotle through Felix Ravaisson, Henri Bergson, Maurice Merleau-Ponty, and Pierre Bourdieu — that understands character and disposition as shaped through repetitive bodily practices.

I am thinking again of Améry’s tattoo. The tattoo serves as a synecdoche for the whole brutal experience of dehumanization and cruelty, of course, but also for his identity: “On my left forearm I bear the Auschwitz number; it reads more briefly than the Pentateuch or the Talmud and yet provides more thorough information.”

But the prime significance of his tattoo is emotional. Émile Durkheim’s discussion of the totems in his canonical sociological text The Elementary Forms of Religious Life is helpful for thinking through Améry’s tattoo. Like the Durkheimian totem, the tattoo is a symbol. On its own, the tattoo and the totem are arbitrary lines. They are only given significance by their presence at the moment when all of the normal boundaries of behavior and relationships were suspended. The suspension of all laws meant different things to each man, of course. Durkheim was talking about the wild carnival atmosphere of festivals, when the collective energy of the tribe floods the individual with a sense of something higher and sacred, while Améry speaks of being overwhelmed by all the feelings of loneliness, fear, and violation present when his tattoo was inscribed in his flesh. But in both cases, the markings are imbued with the feelings surrounding the event. A glance at the sign is enough to bring those feelings back. For Améry, this means that even if he wanted to forget, to shake off the sense of unease that permeates his skin as he walks through a small German town, or the jolt of anxiety he feels when he passes a custom agent, the tattoo remains on his arm, ready to conjure up all the emotions attached to his memory. Like a talisman, it even becomes associated in Améry’s account with the refusal to forgive in the absence of justice. He must not forgive or forget: “The six-digit number on my forearm demands it.” The act of looking at the tattoo creates a habit of not forgiving.

Améry’s case is an extreme one, of course, but he is not an anomaly. People often carry traces of their past harms in their bodily comportment. The adult who flinches back from yelling after an emotionally tumultuous childhood, the sexual assault victim who dissociates from intimacy, the victim of a mugging who speeds up when she sees another person on a deserted street—these are all reactions to past injuries operating below the level of consciousness. They are ways of the body remembering, even if the conscious mind has pushed the injury aside.

All of which raises the question, who—or what—is the person who decides to forgive? Is the person who forgives reducible to the conscious mind, to the will that decides to forgive or not to forgive? Are they emotions, wrestled into a properly benevolent state? Are they some combination—a mind that vows to cease holding past transgressions against the offender, and consciously decides to disregard any lingering feelings of resentment? Or are they, as it seems to be in Améry’s case, some tangle of mind, emotions, and a body that encodes the harm in their very movements? And what happens if the mind agrees to forgive and forget, but the body still remembers? Is forgiveness an act of the will or an act of the body?

These questions matter for academic reasons, of course. There have been thinkers arguing for the integration of mind and body at least since Descartes sat in his study by the fire, examining melted candle wax and trying to define a substance. It is simply strange to have nearly four centuries worth of scholarship theorizing about the connection between mind and body, ranging from empiricism, to physiology, to phenomenology, to feminism, to affect theory, and to carry on all the while as if forgiveness could be some sovereign act of will.

The body, with all of its twitches and trauma, needs to be part of the conversation about forgiveness, otherwise we risk an empty ethics debate —one that is all about oughts and wants and trolley cars, but never about the physical experiences that make forgiveness possible.

But these questions about the body’s role in forgiveness also matter for the people who want to forgive or who feel shamed for their refusal to forgive. Forgiveness is simply a different process if it requires unlearning the habit of glancing at old scars or training oneself to walk boldly down a dark street. It becomes a different, darker, more complicated affair if we acknowledge the ways the wounds we carry on our bodies can undermine even our most resolute intention to forgive. All of the perky promises of heart health in the world won’t be enough to motivate a person to forgive if her morning rituals remind her of her wounds.

Most of all, this insight is what we are missing in all of our endless articles about whether some famous man has shown proper contrition through the right arrangement of words. The broad cultural focus on the men who apologize is many things—an effort to understand the psychology of abusers, a way of holding men accountable, an inadvertent practice of sidelining the experience of women—but it is also an act of profoundly unjustified optimism. Optimism that the right words can be found. Optimism that these famous men are the problem, not the economic system that made them untouchable. Optimism that the right apology will heal wounds. Optimism that victims will want apologies. Optimism that wounds can be healed at all.

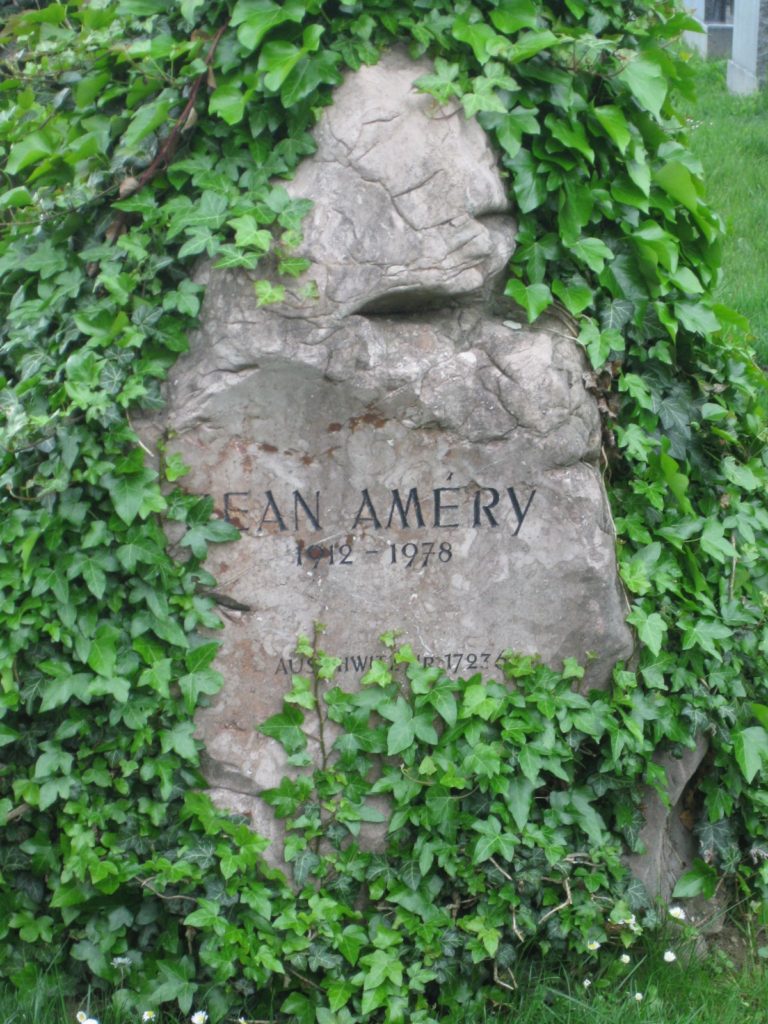

No one knew that better than Améry. His essay collection, canonical as it is, would not be the last comment he would make on tattoos or the memory of flesh.

In the central cemetery of Vienna, there is a jagged rock, covered with ivy, erected the year Améry killed himself by overdosing on sleeping pills. It doesn’t mention either of his wives or his birth name or his profession. Instead, it simply reads:

Jean Améry

1912-1978

Auschwitz Nr 172364

***

[1] In fact, I’ve written much more about this in my book, Contingency and the Limits of History: How Touch Shapes Experience and Meaning, which will be published later this year.

[2] The studies that follow can all be read about in the following edited volume, Loren L. Toussaint, Everett L. Worthington, and David R. Williams, eds., Forgiveness and Health: Scientific Evidence and Theories Relating Forgiveness to Better Health (Dordrecht: Springer, 2015).

***

Liane Carlson is the Henry R. Luce Initiative on Religion in International Affairs Post-Doctoral Fellow at the Center for Religion and Media at New York University. She received her PhD in philosophy of religion from Columbia University in 2015. From 2015-2018 worked as the Stewart Postdoctoral Research Associate at Princeton University. Her book, Contingency and the Limits of History: How Touch Shapes Meaning and Experience, is forthcoming from Columbia University Press in 2019. She is currently working on a new book on the refusal to forgive.

***

Published with support from the Henry R. Luce Initiative on Religion in International Affairs.