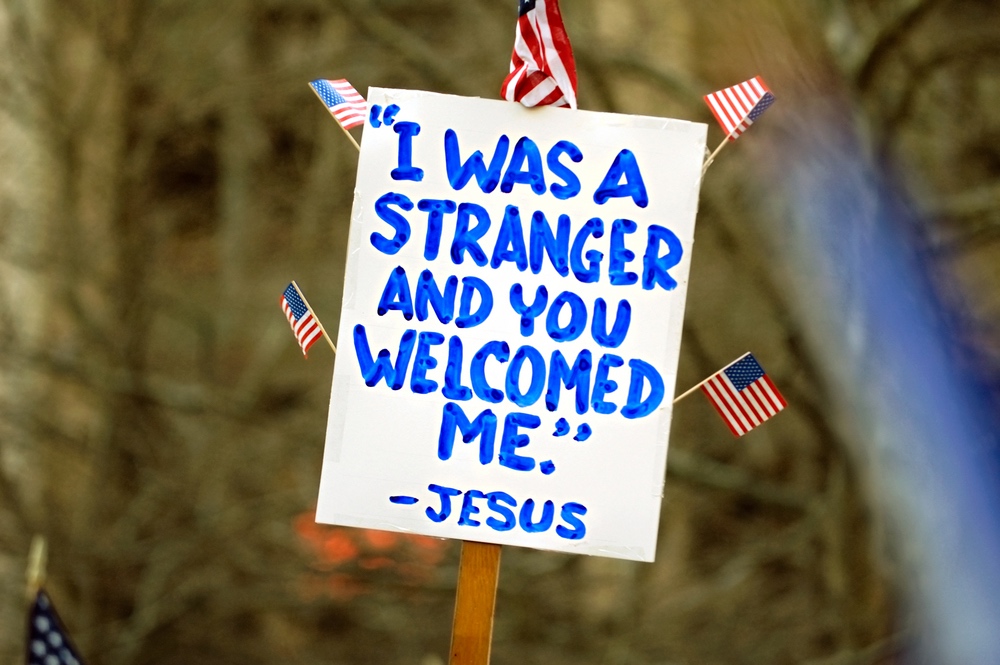

To Evangelical Christians, What Does it Mean to "Welcome the Stranger"?

A surge in White evangelicals working to help immigrants and refugees—and if that influences their politics

(Image source: Jorge Salcedo/Shutterstock)

“I used to say, ‘I’m a Republican – no ifs, ands, or buts,’” said Summer (pseudonyms used throughout this article), an evangelical Christian who runs a food pantry for resettled refugees in the Midwest. “Now, I don’t even know what I am,” she laughed. Summer started volunteering with a faith-based refugee resettlement agency over a decade ago. She has since helped to set up apartments for new arrivals, provided transportation to grocery stores and doctors’ appointments, and taught English to resettled refugees. Now, she runs the resettlement agency’s food pantry program, which provides culturally appropriate groceries for upwards of 60 families per month.

Recalling the array of anti-immigrant policies enacted during the first Trump presidential administration, she reflected, “I didn’t agree with how Trump was treating the immigrants, but then, I had friends that were like ‘well, he’s doing a good thing’ that go to the same church that I do.”

Summer says her experience with resettled refugees has changed the way that she thinks about immigration. “I grew up in a white town, a small town,” she explained. “A lot of white Christians stay in their own bubble, and they lose the empathy for people different than them because they isolate.” But after building relationships with resettled families from Sudan, Myanmar, and Cuba, Summer could not ignore the effects of Trump’s anti-immigrant rhetoric and policies on the lives of her immigrant friends—policies that sowed fear, stoked xenophobia, and further marginalized many, such as Muslim immigrants.

When Donald Trump ran again for president in 2020, Summer reconsidered her vote, and found that her political opinions differed significantly from close family and friends: “They’re like, ‘well, you’ve got to vote Republican’—and I’m like, ‘No, you don’t. You’ve got to think about everything, the [candidate], and what exactly they’re standing for.’”

While some American evangelical groups have welcomed refugees and other immigrants for decades, recent years have seen a hardening of political opinion on immigration in the U.S., with white evangelicals consistently polling as the demographic with the most restrictive and negative views. In 2016, nearly 81 percent of white evangelicals voted for Donald Trump, a candidate synonymous with xenophobic rhetoric and restrictive immigration policies. Exit polling suggests that former President Trump received similar levels of electoral support from this demographic again in 2024. Yet across the country, evangelical Christians like Summer work to aid asylum seekers, welcome immigrants into their communities, and resettle refugees. These welcoming actions, often undertaken at significant cost to volunteers’ own time or financial resources, quietly complicate homogenous xenophobic characterizations of American evangelicalism and divisive national politics.

Since 2016, I have interviewed over 50 evangelical Christians who volunteer or are employed with refugee resettlement activities. What I have learned is that although the Biblical directive to “welcome the stranger” is clear, American evangelicals differ on what it looks like to obey this command today—and exactly who should be responsible for providing this “welcome.” They also wrestle with how their faith should affect their politics, often coming to divergent conclusions about how to weigh their experiences with immigrants as they formulate their political opinions about immigration policy.

***

The United States has historically hosted the largest refugee resettlement program in the world, working with the United Nations’ refugee agency to resettle some of the world’s most vulnerable refugees. Although refugee resettlement has enjoyed relative levels of support among most Americans since the 1980s, the U.S. resettlement program became increasingly politicized in the lead-up to the 2016 presidential election.

Following the onset of the Syrian Civil War in 2011, the number of people forcibly displaced by conflict around the world soared to record-breaking heights. By 2014, international news media was heralding a global “refugee crisis,” as thousands of refugees from North Africa and the Eastern Mediterranean sought passage to Europe in search of safety. In response, President Obama announced in September 2015 that the United States would expand that year’s resettlement admissions ceiling to include 10,000 additional Syrian refugees.

In November 2015, a group of terrorists, some of whom entered the European Union falsely claiming to be Syrian refugees, perpetrated a devastating attack in Paris. Within days of the attack, 31 U.S. governors declared that their states would not accept Syrian refugees. Then-candidate Donald Trump seized on the chance to advance his anti-immigrant campaign rhetoric, characterizing Syrian refugees as a “great Trojan horse” and casting aspersions on the security of the refugee vetting process. A mere seven days after his 2016 presidential inauguration, President Trump issued a series of executive orders aimed at halting the refugee resettlement program and curtailing immigration from seven Muslim-majority countries.

The so-called “Muslim Ban” sparked immediate controversy. Within hours, protests against the ban erupted in airports and major U.S. cities. Legal challenges to its implementation began immediately as advocacy groups filed suits against the administration to halt the order. Two days after the ban’s announcement, leaders of prominent evangelical groups such as the National Association of Evangelicals, the Wesleyan Church, and World Vision, among others, wrote an open letter to President Trump and Vice President Pence asking that the administration “reconsider” the policy, “allowing for resettlement of refugees to resume immediately.” Despite such pushback, Pew Research found that 76 percent of white evangelical Protestants approved of the ban, more than any other socio-religious group. Meanwhile, 59 percent of Americans opposed the ban.

Yet the Muslim Ban was not welcomed as a political victory by all evangelicals. Instead, many evangelicals responded by seeking to learn more about refugees to the United States, what happens once they arrive, and how to welcome them. World Relief, a national evangelical resettlement agency, reported over 6,000 new volunteer applications in 2017 alone. Jenny Yang, the organization’s former Vice President of Advocacy and Policy, described this “overwhelming response” as a result of “people desiring to act locally in response to the global refugee crisis.”

Other evangelical resettlement efforts experienced a similar surge in interest. I spoke with Naomi, a volunteer coordinator at a local evangelical organization in Kentucky that offered post-resettlement support to refugees. She recalled the tumultuous political environment of 2016, explaining that her organization had experienced an uptick in negative feedback via online comments and phone calls during the election season. Local detractors, many of them evangelicals, questioned why a Christian organization would spend time and money to welcome refugees from “Muslim countries” to their city.

Yet after the January 2017 Muslim Ban, the organization began to experience a significant increase in donations and volunteer interest from evangelical churches and individuals. “The Ban itself is a terrible thing,” Naomi said, but “we’ve had a lot more people wanting to get involved [in resettlement work].” She understood this shift to be a result of increased awareness about global displacement among evangelicals in her town: “[The] refugee crisis is more in the media, people have learned more about [refugees] and they’re just more empathetic toward refugees, so they’re more willing to give towards causes that help.”

By the end of 2017, the organization saw 55 congregations and over 750 new volunteers across Kentucky get involved in resettlement support work. Nathan, the organization’s director, viewed this new volunteer interest as directly related to recent attacks on refugees and the resettlement system during Trump’s first year in office. “We didn’t expect it to be like that, this kind of explosion of volunteers and people being willing to help,” he explained. In retrospect, he reasoned that the Trump administration’s polarizing rhetoric and anti-immigrant policies, like the Muslim Ban, had catalyzed more evangelicals to get involved with helping immigrants in their local communities. “Now people are like, ‘Okay, I have to make a decision now on how I feel about this, and I feel like I need to take some action.’” Yet in 2017, it remained unclear if this unprecedented outpouring of evangelical resettlement volunteerism would significantly influence white evangelicals’ electoral choices or political behavior.

***

As evangelicals across the country entered resettlement work to “take some action,” as Nathan put it, many encountered the difficult realities of resettlement for the first time, a far cry from the primarily white, suburban, evangelical circles in which most reside. Many evangelicals I talked to found it challenging to reflect on their experiences in resettlement without recounting how this work had shifted their perspectives on immigration.

Some, like Summer, have experienced a transformation in their political opinions after serving immigrants and refugees in their communities. Others, although moved to compassion, are reluctant to connect their experiences to any overt political stance.

Evelyn, an evangelical employee at a Christian resettlement non-profit in Illinois, shared her frustration that her family and friends have a “stigma” about immigrants. “I never really got that, because in the Bible there are so many important figures that were immigrants themselves, and refugees.”

Evelyn spends her days connecting refugee clients with employment opportunities and helps educate community members about resettlement. She shared that her faith values and a desire to help those in need motivated her work, and that she is frustrated by the lack of empathy for immigrants in her evangelical community. Instead of their shared faith informing how her family and friends see immigrants, she feels that politics hold sway instead. “Really, it’s [their] political view seeping into their faith. And that’s not how it should be.”

Although many evangelicals like Evelyn see a clear connection between the tenets of their Christian faith and their efforts to meet resettled refugees’ needs, few interpret the Biblical command to welcome the stranger as having implications for their political behavior.

When asked how her faith and resettlement experiences shape her opinions on immigration policy, she equivocated, saying instead, “God himself is not political. So why should I be political when it comes to that?”

(Image source: Adam McLane/Flickr)

Many evangelicals I talked to shared how their experiences with resettled refugees challenged them to reconsider their previous concerns about immigration. Trevor, a self-identified evangelical and law enforcement professional, volunteers regularly with a faith-based refugee resettlement agency in Iowa. “It is pretty polarized, even here,” he said. “Even in the church circles, people can be anti-refugee.” Reflecting on his volunteer experience, Trevor says he began with a “superficial level” of compassion. But once he began to connect with refugees and learn from their experiences, his concept of immigration evolved from an abstract understanding to one based in witnessing the challenges of resettlement firsthand—“It was theoretical before, [but] now it’s the real thing.”

While Trevor believes Christians have a moral responsibility to welcome immigrants, he is wary of policy changes that would seek to significantly increase the number of immigrants and refugees in the country. Like many other evangelicals, he supports the idea of compassionate immigration policy. “I am my brother’s keeper,” he quotes, echoing similar sentiments from dozens of others who spoke with me. But, as with many other evangelicals I met, Trevor remains undecided as to what this compassion should look like in practice. “You’ve got to embrace your limits. You can’t help everybody all the time,” he said, referring to the resettlement program.

Other evangelicals oppose policies that bring immigrants to the United States but choose to show hospitality to newcomers to their local communities nevertheless, welcoming refugees in spite of, rather than because of, their personal politics. Rachel, a volunteer with an evangelical resettlement organization in Illinois, was motivated to join resettlement efforts in her area following new waves of displaced people from Ukraine and Afghanistan as a result of escalating conflicts in those countries between 2021 and 2022.

Despite her desire to help refugees displaced by those violent conflicts, Rachel told me that she has serious concerns about security in the immigrant admissions process and wants to see “some sort of, throttle—to control, [not] letting [just] anyone in, because of the consequences to America, if just a billion people decide they want to live here.” She remained concerned that the resettlement process, especially for Afghans arriving on humanitarian visas, does not sufficiently vet the backgrounds and motivations of potential newcomers. “Just because they [Afghan refugees] helped America, they must be a good person […] that’s an inaccurate assumption,” she said.

Despite reservations about resettlement policy and concerns about security, she doesn’t believe her political opinions should influence her interactions with immigrants, nor do they prevent her from working to welcome recently arrived refugees as a volunteer. “I believe that regardless of how [refugees] got here, they are here. And they are not just in America. They are in my town,” she explained (emphasis original). She insisted that her politics do not govern the imperative to show hospitality to newcomers in Jesus’ name.

Rachel’s decision to volunteer with refugees has garnered mixed responses from her evangelical family and friends. “I haven’t had many people come out and say disparaging things,” she says, but, “political comments are made.” Her response? “I always go back to the fact that these are human beings that are here, regardless of how they got here.” Although emphasizing the humanity of resettled refugees, Rachel’s position sidesteps larger political implications by focusing on individualized, local needs rather than broader systemic causes or policies.

Like Rachel, some evangelicals ignore the political implications of their work, instead focusing on the physical and “spiritual” needs of refugees. Kate, an evangelical employee of a faith-based non-profit, told me that she was initially drawn to resettlement work because she imagined that she would have the opportunity to “spread the name of Jesus” among refugees who are arriving in the United States. However, after learning more about the resettlement process, she was quick to clarify that volunteers are not allowed to proselytize, which she defined as “[saying] ‘if you don’t believe what I believe, then I’m not going to help you,” Instead, Kate seeks to share her faith by “showing love,” but eschews any form of overt evangelism or coercion in her work, saying that such an approach would not be “Biblical” at all.

Regardless of how evangelicals make sense of their resettlement experiences, I found that few carry their convictions about immigration through to meaningful political action or advocacy, instead containing their experiences at the level of personal transformation rather than political engagement. These evangelicals argue that it is not the government but “the Church” (and “believers,” or evangelical Christians), who are best suited to welcome the stranger in the U.S. today, regardless of who wins an election.

Reuben, an evangelical pastor-turned-resettlement-entrepreneur, helps to run a post-resettlement support organization in the southeast United States. Reuben’s organization works to “fill the gaps” in the federal resettlement program by providing long-term support such as vocational training, language and citizenship classes, and continuing education to refugees. During Trump’s first administration, his organization grew significantly, working to welcome refugees into their local area despite significant cuts to the resettlement system and restrictive federal immigration policies.

While Reuben and his volunteers are well aware of the limitations of the federal resettlement program and the Trump administration’s disruptive executive actions, the organization’s ethos embodies a different response. Rather than advocate for better or more inclusive immigration and resettlement policy, Reuben does not believe the solutions lie in political action—instead, “the Church” should fill the gap. “There is no one who’s better equipped to show hospitality and welcome than a [Christian] believer,” he argues. Echoing a common refrain in evangelical theology, God has forgiven and “welcomed” people into his own family through the sacrifice of Jesus Christ.

In this view, resettlement agencies, government programs, and immigration policies should not ultimately be responsible for welcoming immigrants and meeting the needs of resettled refugees—instead, because Christian believers have “themselves been welcomed by God,” Reuben and other evangelicals I talked to argue that it is not primarily the responsibility of the government or of federal programs to welcome the stranger; rather, they interpret the Biblical directive to welcome the stranger as a command that has been given directly to Christians. “We just think that they [government programs] don’t have the capacity […] like a believer does,” Reuben explains.

***

In 2020, exit polls indicated sweeping support for then-candidate Trump among white evangelicals, with somewhere between 76 and 81 percent casting their vote for the former president. And in 2024, these levels of electoral support remained unchanged—nearly 81 percent of white evangelicals voted again for President Trump, preliminary polls show. Despite pushback from some evangelical leaders and institutions, and a surge of white evangelicals interested in welcoming immigrants during the first Trump administration, overall white evangelical support for Trump, and his exclusionary immigration policies, remains high.

Rather than voting for politicians and policies that would serve to better “welcome the stranger,” evangelicals involved in resettlement primarily choose to translate their convictions, concerns, and compassion about immigration issues into individual action that takes the form of localized volunteer efforts.

This type of resettlement work typically requires effort, a sacrifice of time and money, and a willingness to encounter and empathize with individuals from different backgrounds. And evangelicals who work closely with immigrants and refugees in these roles are quick to expound on how these encounters have changed their own lives and perspectives.

Yet even believers united by a shared faith and moved to take common action in the form of local resettlement work arrive at conflicting conclusions about what the Biblical command to “welcome the stranger” should mean personally and politically. For many white evangelicals, even profound personal experiences with immigrants and refugees do not appear to be enough to sever their ties with anti-immigrant Republican Party politics.

These differences point to the fact that appeals to common beliefs or even “Biblical directives” are not guaranteed to mobilize evangelicals to act on pro-immigrant politics or form a cohesive welcoming movement.

Emily Frazier is an assistant professor of human geography at Missouri State University. She researches and writes about refugee resettlement and faith-based humanitarianism in the United States, and her work has been published in multiple academic and public-facing outlets.