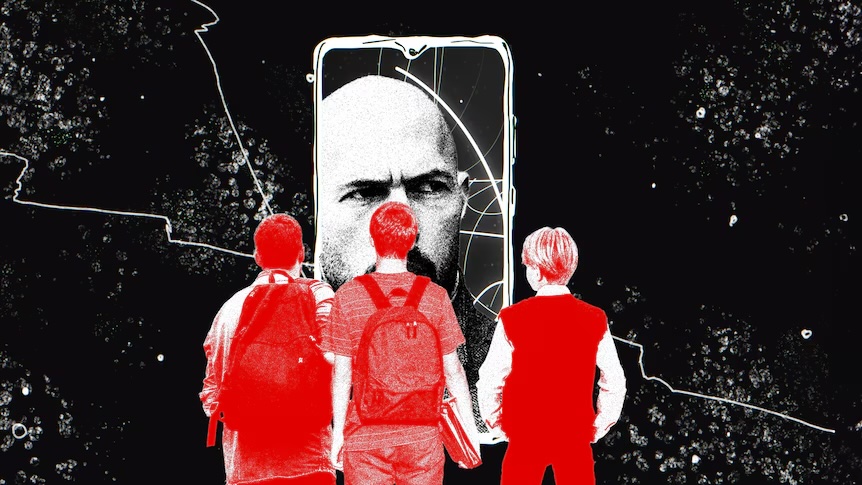

TikTok Masculinity

Gen Z men, their rising conservatism, and interest in religion

(Image source: Sam McKenzie/BTN High/ABC News)

Ariel, a 21-year-old sophomore male at New York University, grew up in a politically liberal Hispanic family where both of his parents are academics. But today, Ariel describes his views as conservative-leaning.

“I think this is part of what is sort of driving me towards conservatism; people are talking about a ‘chilling effect’ happening right now on elite universities with free speech—I would definitely agree, but I think it’s going in the direction against conservative voices instead of left-leaning ones,” Ariel said to me, citing the plethora of left-leaning faculty and staff at the university, as well as the school’s left-leaning student body.

“We do have a shortage of conservative voices on campus, and I think that’s part of the thing that also makes a lot of young men in my demographic feel so alienated as well. We go to school, and we don’t really see any of our political dispositions reflected in the classroom.”

A common assumption among pundits and political commentators is that each generation is more progressive than the preceding one, and in the early 2020s, polls suggested that Generation Z (or Gen Z for short, which includes those born between the mid-1990s to the early 2010s) was more progressive than Generation X or even Millennials. At the height of the COVID-19 pandemic, Pew Research Center found that Gen Z was both progressive and “more racially and ethnically diverse than previous generations”—signs that would support the pundits’ prognostication. However, President Donald Trump’s second electoral victory highlighted the Republican party’s social-media outreach and the capture of a sizable portion of Gen Z voters, particularly white Gen Z men, who voted for Donald Trump in 2024 by roughly 64%.

Ariel’s story is just one example of the millions of Gen Z men who are drawn to political conservatism, religion, and traditional gender roles. Understanding why so many Gen Z men are moving to the right is necessary if we are to make sense of today’s political climate and the ways this will affect American culture and politics for decades to come.

Men’s Liberation, Men’s Rights, and the Manosphere

The second coming of Donald Trump in 2024 revealed the cultural and political leverage of the “manosphere”—a portmanteau describing the online communities and collection of websites, social media accounts, and podcasts promoting masculinity and opposition to feminism. Influencers like Jordan Peterson and Andrew Tate became synonymous with this loosely connected network of “men’s rights” activists and self-proclaimed alpha male influencers. Nearly 50% of young men in one survey reported that they trust voices in the manosphere that promote “anti-feminist” or “pro-violence” ideas.

Paradoxically, the philosophical and ideological roots of this manosphere—a space in which male grievance and pain generally lay front-and-center—can be located alongside the contemporary feminist movement.

The cultural currents of 1960s and 1970s civil rights activism and equality—values that propelled the rise of the Women’s Liberation Movement and Second-Wave Feminism—also gave birth to the “Men’s Liberation Movement.” As a response to Women’s Liberation, the Men’s Liberation Movement supported feminism’s goals by advocating for releasing men from their traditionally masculine roles as unemotional and stoic providers and breadwinners.

From its beginning, the Men’s Liberation Movement faced internal tensions—most notably the paradox of acknowledging that, while men benefit from systemic privileges, they are also harmed by certain pressures tied to masculinity—like the pressure to be less emotionally vulnerable and thus less socially connected. This dichotomy led to splintering within the movement, with a pro-feminist wing of Men’s Liberation, and a “Men’s Rights Movement”—a movement that stressed the perceived harms society causes men and how it persecutes them—such as criminal cases of domestic violence (especially if the male is the victim), divorce court, and family custody battles that favor mothers over fathers. Most importantly, the Men’s Rights Movement saw their oppression on equal terms with women, and it blamed feminism for ignoring, if not causing, men’s collective problems.

(Image source: The Security Distillery)

The Men’s Rights Movement laid the groundwork for many of the narratives now pervasive in the manosphere. And the manosphere has never been bigger than it is today. Donald Trump’s outreach toward key manosphere influencers is at least one reason why young men shifted roughly fifteen points toward the right in the 2024 election.

Although the manosphere is influential, it doesn’t account for shaping Ariel’s political outlook.

“None of those figures have been influential in my intellectual development at all. I’ve never turned on Ben Shapiro or Charlie Kirk wondering what their take on a political topic is,” Ariel told me. “They just haven’t been a part of my political constellation.”

Ariel’s political formation started in 2020 as a high school sophomore during the COVID-19 pandemic, racial protests spurred by the murder of George Floyd, and Biden’s election.

“When there started to be super large gatherings of people outside and, at the same time, there is this really deadly pandemic happening, that fundamentally did not make sense to me,” Ariel said to me over the phone. He also found the posting of black squares across social media, a form of solidarity with Black Americans, as off-putting.

“At some point, my peers started posting black squares to show solidarity with the Black Lives Matter movement, which I just found absurd. There’s activism I respect, and there’s activism that I think is barely activism—posting a black square is more virtue signaling. I really felt that summer was that a lot of what people were doing was just virtue signaling to each other.”

While concerns about how people protested in 2020 frustrated some like Ariel, the concurrent COVID-19 pandemic revealed vast inequities within society, and, for many, it ignited reflections on death and mortality. And consequently, a sizable number of Americans, including Gen Z men, have reportedly found a renewed interest in religion.

Gen Z Men and Religion

A commonly held maxim in American society, at least since the 1960s, has been that “religion is declining.” Yet since 2024, there have been reports of a religious “revival” of sorts in the United States, the United Kingdom, and across Europe — geographical locations that have experienced religion’s decline most potently.

Among the renewed interest in religion, conservative religion is especially popular. Roman Catholicism and Eastern Orthodox Christianity are seeing a rising number of converts joining their parishes, and young people are flocking to evangelical Christian church services. Outside of Christianity, Orthodox Judaism is poised to hold the largest share of religiously-observant Jews in the United States by around 2050.

And this trend is led by Gen Z men.

I talked with Father Charles Gallagher, the pastor of Immaculate Conception Church in Washington, D.C. about the rise of Gen Z men within Roman Catholicism and the factors that might be contributing to it. Last April during its Easter vigil, his parish baptized seven converts into the Catholic Church, and six of them were Gen Z men.

“I think they’re finding that [Catholicism] has a robust kind of intellectual foundation,” said Father Gallagher.

“Many of them have explored the spectrum of various religions—including within Christianity—and have landed on Catholicism because of its coherence and its persuasive message. They may not know if they will be able to follow every teaching, but they still see in Catholicism something captivating and compelling since a lot of the church’s teachings have a very firm and philosophical foundation.”

For decades, surveys showed that women were “more religious” and had higher rates of church attendance than men. Now, the gender gap on religion is shrinking, and the novelty of religion in America today is that, compared to generations past, religion is starting to become coded as a masculine pursuit.

Traditions like Roman Catholicism, Eastern Orthodoxy, and large segments of evangelical Christianity, tend to promote strict gender roles and divisions. Women can’t become priests in the Roman Catholic or Eastern Orthodox Churches, and they can’t become pastors in many evangelical congregations. Gender roles in these religious circles are God-ordained and infallible. Gender is fixed.

“An attractive thing that we have, as Catholics, is a philosophy and an anthropology that is biblical,” said Father Gallagher. Gallagher compared the structure innate to Roman Catholicism with that of secular culture.

“Whether it’s gender, sexual ethics, divorce, the death penalty—whatever it might be, we have a tradition that is both based in the Bible and the magisterium of the church, where we have a clear body of teachings about these certain things. It gives men a very clear moral compass, and I think that it’s what they’re looking for.”

The Gender Shift – Gender, Identity, and Faith

Gen Z men have come of age at a time of prominent cultural debates about gender and sexuality. When then-president Barack Obama endorsed same-sex marriage in 2012, and the Supreme Court made same-sex marriage legal in all fifty states in 2015, groups that had fought marriage equality shifted their attention to transgender Americans, highlighted by the “bathroom wars”—a controversy conservatives started to try to insist people must use bathrooms that matched their assigned sex at birth.

While Trump’s first term worked towards the repeal of Roe v. Wade, in his second term his administration has shifted its focus to repealing transgender rights.

One issue that motivated voters in the 2024 election was transgender children and, more broadly, school materials that include LGBTQ representation. This issue is one that Ariel leans most conservative on, which he says is because he has two pre-adolescent younger sisters.

“I don’t necessarily have a problem with queer politics—but I think that the sort of imposition onto really young kids is sort of unnecessary,” Ariel said.

“Discussions about gender and sex and where they intersect and where they don’t, those are really interesting conversations, and I’m actually interested in having them, but I don’t necessarily think they’re very helpful for developing minds.”

While Ariel is personally more open to these kinds of conversations, other young men believe that conversations about gender and sexuality have been monopolized by feminists and LGBTQ activists and, in turn, have promoted ideas about the harms of patriarchy and “toxic masculinity.” Many say this has created a vacuum for young men seeking both meaning for their lives, and approval for themselves as men.

“I look at what these [religious] institutions are offering to young men in a moment where there are umpteen stories about young men struggling in the United States in terms of their educational achievement, their social class, social standing, and self-conception—what these churches are offering, in many cases, is an unapologetic affirmation of their status as men, and specific depictions of what it means to be men in the 21st century,” said Leah Payne, Associate Professor of American Religious History at Portland Seminary.

Some don’t see the resurgence of religion among young men as a bad thing. MSNBC’s Joe Scarborough argued that Gen Z men’s increased church involvement might serve as a “reality check” for those prone to conspiracy theories or extremist views. However, some view this development as an alarming trend toward radicalization.

“What we’re seeing right now is a more muscular, gendered, and violent vision of Christianity that’s being employed to support the policies of [the Trump] administration,” said Angela Denker, a Lutheran pastor, journalist, and author of Disciples of White Jesus: The Radicalization of American Boyhood.

“The radicalization of young men and what’s happening with these appeals towards violence and towards increasingly traditional religion—what we’re really talking about isn’t a conservative movement inherently, but a fundamentalist movement.” Denker said. “I always tell people that one of the ways to really tell if you’re dealing with a religion that is rooted in fundamentalism or a religious movement that’s fundamentalist is how they understand gender.”

(Image source: Getty/1 News)

And yet, despite the coverage about Gen Z men’s interest in religion, some experts are skeptical that a “religious resurgence” is actually happening.

“Is there a religious revival with Gen Z? The answer is no,” said Ryan Burge, political scientist and professor of practice at the John C. Danforth Center on Religion and Politics at Washington University in St. Louis.

“Something got in the groundwater of the mainstream media that has convinced people that there’s a return to religion happening in America, but that’s not what’s happening.”

Burge and others contend that we’re not witnessing a resurgence or “revival” of religion as much as a plateau—in other words, religion isn’t rising but its decline is leveling out. But that doesn’t necessarily mean that there isn’t a trend happening with Gen Z men.

“Is it that they are becoming so much more religious? I don’t know because I’ve seen push back on that number—but they do seem enlisted,” said Erica Ramirez, a religion sociologist and Senior Director of Research and Strategic Initiatives at the Louisville Institute. “They do seem activated, and I’m hearing that they are becoming activated in surprising ways.”

The story, then, might not be that Gen Z men are becoming more religious or that there’s a “Gen Z revival” led by men—the narrative might actually be that Gen Z men and women are being driven further apart on politics and religion than in generations past.

Gen Z Women Leaving the Church

May, a 29-year-old woman at the upper cusp of the Gen Z generation, is a teacher in Washington, D.C., and describes herself as a “spiritual agnostic.” She was raised Lutheran and converted to Roman Catholicism, alongside the rest of her family, at the start of her high school career.

She attended a conservative Catholic college on the east coast, where she was introduced to traditional (or colloquially, “trad”) Catholicism—now seeing a resurgence in American culture and reflected in social-media communities like Instagram and TikTok. There, she was introduced to Catholic women wearing veils, strict adherence to meatless Fridays, and the Latin Mass with its polyphonic and choral singing.

“I didn’t even know that these things existed because I was just used to there being guitars at Mass or a regular organ,” May told me over the phone.

“It kinda felt just like stepping into this weird Pre-Vatican II world.”

During her junior and senior years of college, May’s involvement with homeless outreach led by Catholic missionaries spurred her religious evolution to becoming a “Dorothy Day Catholic,” a reference to the founder of the progressive Catholic Worker Movement. Even still, May described her faith-based, social-justice work alongside her fellow students as mostly “out of touch” with the realities of those they were serving.

“We’re out here with these individuals experiencing homelessness in Boston, and they’re telling us about their lives and what led them to where they are now, and we’re just like, ‘Do you want to hear about [Thomas] Aquinas?’” She said during our interview.

“I remember having that experience and thinking, ‘I need to break down my world a little bit more—the purpose of living is to bring good to the world; I don’t really think I’m doing that.’”

She graduated in 2019 and joined a year-long teaching residency in the Bronx, New York. By 2020, her residency closed due to the pandemic, where questions started coming up for her about her faith, given the split views within American Catholicism regarding COVID-19 vaccines. Later, in 2023, coupled with traumatic personal events in her life, conversations with her Eastern Catholic convert boyfriend led to further questions about her Catholicism and gender roles within the Church.

“As we dated, he became increasingly more conservative and increasingly more radical, and there were a lot of conversations that we had where I thought, ‘That’s not really right,’” she said to me over the phone. She then decided to leave Catholicism, and religion, for good.

“It was in conversations with him where I realized I didn’t like this [religious] system that’s set up to give men as many rights as they possibly can give them, and then women are just kind of like, ‘Oh well, my path is different—I may have the feminine genius, but I don’t have an actual right to do anything.’”

For Gen Z women, the rights many of them feel they have gained by liberalism (reproductive rights, workplace and income equality, gender discrimination laws) puts them at odds with religious traditions that require members to adhere to strict gender protocols, where men are the breadwinners and women take care of the home.

There are also economic drivers behind the widening gap between Gen Z men and women, which in some ways also connect to religion.

“The young woman in America is working hard in her 20s and 30s to earn a living, and she’s surviving in a big economy. These things take a lot of energy,” said Ramirez.

As young women have been earning more college degrees than men since around the mid-1980s, and the gap between women and men in the workforce has decreased to its lowest levels in the United States, women are no longer as religiously active. At the same time, reports about the widening gender education-gap, the unemployment rate of college-educated men, men’s falling income relative to women, and their general decline of mental health and wellbeing, have even gotten the attention of former President Obama, who called for progressives to “pay attention” to the plight of men and boys.

“The Man Problem” – Gen Z Men and the Struggles of Masculinity

As the 2024 election and a cornucopia of thought-pieces point out, the American Left and the Democratic Party have a “man problem.”

And as reports of the “male loneliness epidemic” have only increased since the pandemic in 2020, religion not only provides a sense of community, but through traditions, rich metaphors and symbols, and historical teachings, a deeper sense of meaning that transcends time and place within a chaotic world.

“There is something about our heritage of worship that has a real beauty to it, and men love that stuff,” said Father Gallagher. Gallagher told me that, while his parish isn’t necessarily “trad Catholic,” he incorporates some traditional elements within the Mass—like portions of the liturgy translated into Latin, or kneeling to receive the Eucharist. He cites these practices as one reason why his parish has been seeing numerical growth.

Religion and political conservatism have become a home for many Gen Z men because they fill a void that the political left and secular culture have left wide open.

Perhaps the situation is similar to the paradox that plagued the Men’s Liberation Movement—can the Democratic Party acknowledge the harms that men are experiencing in society today while also holding a pro-woman, pro-LGBTQ platform?

I asked Ariel what the Democratic Party could do to win Gen Z voters like him. Ariel replied, “I mean, this is literally the multi-million-dollar question.”

Miguel Petrosky is an essayist, writer, and journalist based in Washington, D.C. and has written for The Revealer, Sojourners, ARC Magazine, and Christianity Today. You can follow him on Bluesky @miguelpetrosky.bsky.social.