More than Missionary

This Future Must Not Be Forever

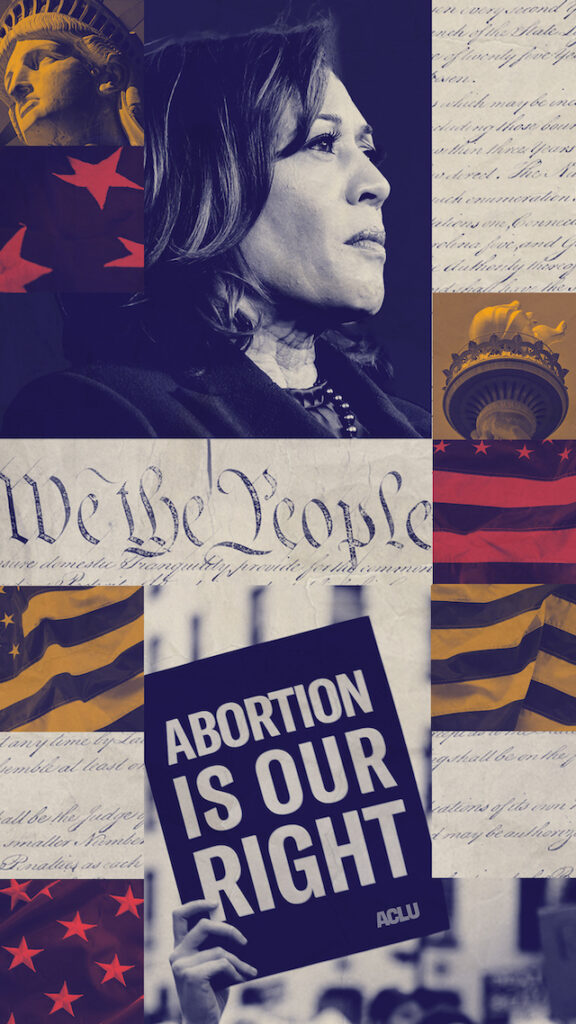

Battles over abortion expose a malignant hatred of women’s freedom

(Image source: ACLU)

How many must suffer or die until reproductive healthcare is made available and legal to all? This question, powerfully present in the recent election, has been asked in various forms about contraception and abortion for well over a century in the United States. What’s more, making the harms caused by abortion bans and contraception bans visible has been a longstanding strategy in the ongoing campaign for reproductive freedoms. But this effort, today, as in the past, has taken place against the backdrop of pervasive hostility toward women and toward gender equality.

Earlier this year, the Public Religion Research Institute’s 2024 American Values Survey saw 44% of respondents agree or strongly agree that, “Society as a whole has become too soft and feminine.” Their findings were echoed by a CBS News/Yougov poll wherein 43% of men indicated that “efforts in the U.S to promote gender equality have gone too far.”

This misogyny informed the election and its outcome. Kamala Harris made restoring reproductive rights to American women a pillar of her presidential campaign. Her opponent gloated that he had overturned Roe v. Wade. Harris’ campaign spotlighted the physical and psychological harms inflicted upon women because of abortion restrictions. Her opponent simulated oral sex on a microphone during a rally but was silent on the public health crisis created by Dobbs v. Jackson.

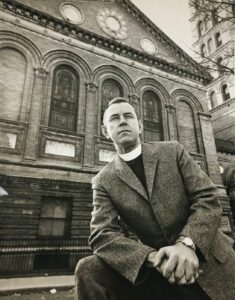

The visibility given to abortion seekers and their suffering during this election season was unprecedented in the U.S. But the deliberate sharing of women’s stories in order to effect change has a long religious and feminist history. In 1967, for example, Christianity and Crisis published an article by the Reverend Howard Moody in which he railed against the country’s abortion restrictions. Moody gave powerful examples of how abortion laws punished sexual assault survivors and those with non-viable pregnancies.

(Rev. Howard Moody. Image source: Village Preservation)

To dramatize the barbarity of such laws, Moody envisioned a future in which abortion prohibitions no longer existed. A citizen of the 22nd century, he imagined, would come upon the “remains of American civilization” and be baffled and horrified by “archaic” abortion laws that “somehow seemed designed to protect human beings” but were in fact nothing more and nothing less than an “unforgivably cruel punishment” directed at women and “stemming from some inexplicable hostility on the part of men.”

An American Baptist, Moody was just one of many mainline Protestant and Jewish clergy who wrote and agitated against the “gross injustice of an inhuman” abortion law in the 1960s. These religious leaders were themselves participants in a wider conversation among journalists, lawyers, social workers, and politicians about how abortion laws created a sea of suffering and preventable deaths while making women into second-class citizens. And for decades prior, these same groups had called attention to the plight of women being denied contraception. Women’s emancipation, they knew, depended upon their reproductive freedom.

When Howard Moody called for the eradication of abortion laws in the pages of Christianity and Crisis, he was working within a religious tradition that taught people of faith to respond to injustice by bearing witness to and challenging the systems inflicting suffering. In the early 1960s, the suffering of both abortion seekers and those compelled to bear unwanted children was shrouded in silence and secrecy. Bringing these hidden harms to light, clergy believed, would provoke righteous indignation and social transformation. As one religious organization–the Clergy Consultation Service on Abortion–put it, the aim was to “bring light and hope to the thousands of people who suffer — usually in quiet, and sometimes in death — the miseries and heartbreak of backstreet abortions.”

Such abortion rights efforts yielded victories, if uneven ones, first at the state level and then at the Supreme Court. After Roe, advocacy groups and scholars documented the not-so-hidden histories of how abortion restrictions violently impact women. The haunting images of women like Gerri Santoro—who died from a botched abortion in a motel room—have been ubiquitous for decades. Projects like Shout Your Abortion have painstakingly recorded women’s histories with abortion. And journalists have broadcast the perils of abortion seeking in a post-Dobbs world. The archive of suffering is vast and visible, and it is growing.

The process of bearing witness assumes that those who are forced to look at suffering will offer compassion. The abortion wars of the past half century have pivoted on the question of who should be given compassion, the mother or the fetus. Indeed, the anti-abortion movement has, through powerful visual rhetoric, literally foregrounded fetuses in hopes of erasing women from the picture.

But no amount of graphic fetal imagery has completely excised the grim and very-well-known truths about what happens to women when abortion is a crime. That the brutal consequences of abortion restrictions have been apparent and tolerable, if not desirable, to significant swaths of the American population brings us to a miserable and heartbreaking if obvious fact. Nested in the fetal images, which are meant to compel compassion toward the unborn, is a malignant hatred of women’s freedom.

The words of the Republican gubernatorial candidate in North Carolina made as much plain: “Abortion in this country is not about protecting the lives of mothers. It is about killing the child because you weren’t responsible enough to keep your skirt down.” And that misogyny, which was barely subtext before Dobbs, has erupted in the wake of the election. The phrase “Your body my choice”—a rebuttal of the reproductive rights mantra—has caught on in right wing circles in recent days.

More than half a century ago, it was revelatory when Howard Moody declared that abortion restrictions were “man’s vengeance on woman” even as he dreamed of a day when gender equality would prevail. With the election of a candidate whose abuse of women is well known, who campaigned on the fact that he engineered the overturning of Roe v. Wade, and who has returned to power promising his base that he would be their “warrior” and their agent of “retribution,” it is apparent that cruelty toward and the suffering of women is the point. A future in which misogyny and reproductive bondage are a thing of the past feels farther away than ever.

Gillian Frank is an Assistant Professor in the History of the Modern United States at Trinity College Dublin. His book, A Sacred Choice: Liberal Religion and the Struggle for Abortion Before Roe v Wade, is forthcoming with University of North Carolina Press.