The Way Black: Considering Black Membership in the Cult of Gwen Shamblin

A review of the HBO Max docuseries The Way Down and the place of Black Americans in Christian diet culture

(The Way Down poster. Image source HBO Max)

The Way Down: God, Greed, and the Cult of Gwen Shamblin debuted in the fall of 2021 and, if Twitter is any indication, the series received an enthusiastic, and somewhat perplexed, response from its audience of HBO Max subscribers. Chronicling the rise and literal fall (spoiler alert: the story ends in a fatal plane crash) of Shamblin’s world-renowned Weigh Down Workshop program and her church, Remnant Fellowship, the five-episode series takes a deep dive into the world of Christian diet culture. Viewers seemed taken aback by Shamblin’s signature ultra-teased bleach-blonde hair-do and confused that someone with such a unique style had amassed so many followers. But to understand Shamblin’s international popularity, we must start at the beginning with her upbringing in the 1950s and 60s by a white evangelical family in Memphis, Tennessee.

As one interviewee in the docuseries aptly describes, Shamblin was formed in a southern religious culture that lived by three tenants: “nobody else but Jesus, nobody even close; the Bible is literally true.” As members of the Church of Christ denomination, Shamblin’s family was guided by Restorationism, a theological movement founded in the 19th century that committed to practicing Christianity in its “purest” form or, as scholars Gerard Mannion and Lewis S. Mudge say, “practicing church the way it is perceived to have been done in the New Testament.” The Church of Christ is widely held as one of the most conservative evangelical denominations, even amongst its southern Protestant peers.

In college and graduate school, Shamblin studied dietetics and nutrition, a decision informed by a self-proclaimed “restless” relationship with food as a child. In 1986, after establishing a career as a registered dietitian, Shamblin started Weigh Down Workshop which was “originally founded as a secular program in Memphis,” according to religion scholar and author of Born Again Bodies, R. Marie Griffith.

It wasn’t until the mid-1990s that Shamblin connected her ideas about nutrition to the theology of her youth. Shamblin began hosting her Weigh Down gatherings in churches and inflecting her curriculum with an evangelical bent. Groups that met to support each other through the program were now referred to as “bible studies,” and Shamblin prescribed prayer “for those in doubt about how much to eat.”

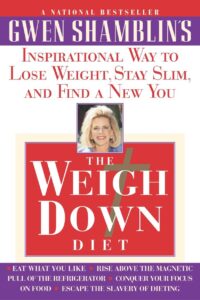

Following this shift, Shamblin’s movement quickly expanded, leading to the publication of her astoundingly successful book, Weigh Down Diet in 1997, which sold more than 1.2 million copies. The text combined “intuitive eating ideologies” that encourage people to listen to their bodies’ signals to properly assess their hunger and fullness with a “theology of thinness,” wherein a person’s morality and sense of worth is judged by their body size. Fat people, according to Shamblin, are not holy people.

Following this shift, Shamblin’s movement quickly expanded, leading to the publication of her astoundingly successful book, Weigh Down Diet in 1997, which sold more than 1.2 million copies. The text combined “intuitive eating ideologies” that encourage people to listen to their bodies’ signals to properly assess their hunger and fullness with a “theology of thinness,” wherein a person’s morality and sense of worth is judged by their body size. Fat people, according to Shamblin, are not holy people.

Weigh Down was neither the first nor only Christian diet program to emerge at this time. Several others like Joan Cavanaugh’s More of Jesus, Less of Me and Slim for Him had circulated since the 1970s. The Southern Baptist Convention had also established its First Place program five years before Weigh Down Workshop and, similarly to Weigh Down, “reasoned that if, as believers, [Christians] could turn to God for a wide range of personal struggles, they should be able to call on him for help in the realm of fitness and weight loss,” writes religion scholar Lynn Gerber. Even Black mega-pastors, like T.D. Jakes, joined the fray. According to Griffith, Jakes’s Lay Aside the Weight borrowed from white Protestant theologies of bodily perfection. Influential church leaders across the country were figuratively and literally sharing recipes for thinness.

Though the Southern Baptist Convention’s First Place may have beat Weigh Down to the punch, Weigh Down Workshop far outpaced its competition. By 1998, Weigh Down Workshop developed a mega-following and hosted over 21,000 classes with more than 250,000 participants across the United States, Canada, and Europe. The Weigh Down Workshop’s popularity, and the Weigh Down Diet’s massive book sales, provided the foundation for Shamblin to establish her own church, Remnant Fellowship, in Franklin, Tennessee, about 40 minutes outside of Nashville.

Over the course of the docuseries, viewers watch scholars, clerics, and local residents discuss the church’s impact – the good, the bad, and the ugly. Ex-members describe an atmosphere that welcomed them with open arms, where everyone felt included. It seemed like the perfect, ready-made community, at least in the beginning. Several spoke of the impressive schedule of events curated to fill members’ social calendars. Seemingly kind and altruistic leaders provided encouragement and guidance to help people on their intermingled spiritual and weight loss journeys. However, somewhere along the way, that kindness turned into exploitation. Some would describe this experience as love-bombing, a strategy where people lavish others with attention and praise in order to manipulate them.

The documentarians behind The Way Down deployed this strategy to frame Remnant Fellowship as an abusive cult. Allegations of spiritual malpractice ranged from Shamblin blackmailing Weigh Down Workshop employees to her covering men’s legal fees when their wives wanted to leave the church and get a divorce. Several children were also allegedly abused by adult Remnant Fellowship members. Throughout its time, Remnant Fellowship made frequent headlines with abuse allegations, legal woes, and even claims of heresy from nearby pastors. In the end, things literally came crashing down when several Remnant Fellowship leaders, including Shamblin, died in plane crash piloted by Shamblin’s second husband.

***

As I watched the docuseries, I was most struck by the presence of Black interviewees who discussed their experiences as Weigh Down Workshop participants and Remnant Fellowship members. Both Weigh Down and Remnant Fellowship perpetuated anti-blackness, using language of “bondage,” “enslavement,” and “freedom” to describe relationships with God and food. And their standards of beauty and femininity clearly positioned white womanhood as the universal ideal.

As the series aired, Twitter users questioned why Black people became involved in such an organization.

“The Black lady on here says other Black people shouldn’t judge her because she was just looking for like minded people. I’m sorry but as a Black woman – white evangelicals could never be likeminded to me,” one person tweeted.

“How do Black people keep getting caught in these cults??? What is alluring about this?” asked another.

Glaringly absent from the documentary was any significant analysis of Black people’s participation in Remnant Fellowship and Weigh Down Workshop. The series made sure that Black people and people of color were represented throughout the episodes. But there was no mention of how Black people were groomed for this type of environment or the racial dynamics that occurred therein.

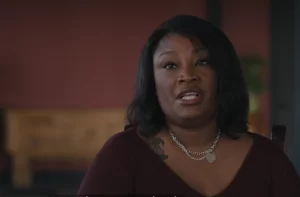

(Helen Byrd in The Way Down)

One example of this can be found in the portrayal of Helen Byrd, a Black woman profiled in the series. In an earlier podcast interview, Byrd said she joined Remnant Fellowship because she wanted to be connected with a community of Christian believers. Having relocated from New Orleans to Nashville in the wake of Hurricane Katrina, she longed for a personal relationship with God that was different from her Catholic upbringing.

With Byrd’s story as a case study, The Way Down’s documentarians could have offered viewers insight into why Black Americans like Byrd were drawn to Remnant Fellowship. For example, they could have highlighted New Orleans’s large Black Catholic population and the decades-long history of interracial worship there to help viewers understand why such Black Americans might feel comfortable in Gwen Shamblin’s congregation. They also could have explored whether or not Black Americans’ displacement from New Orleans following Hurricane Katrina, and the ensuing desire for a new community with strong social ties, made people like Byrd vulnerable to being groomed for membership by Remnant Fellowship leaders.

As I reflected on Black Christians’ involvement with Remnant Fellowship, my mother reminded me that we attended a Weigh Down Workshop meeting at Remnant Fellowship when I was 11 years old. We were invited by the wife of mom’s long-time OBGYN. The gathering was not what my mom expected so we left with no intentions of returning (or really thinking about it ever again), that is until my mom received a letter from Remnant Fellowship saying the Lord really wanted her to be with them and that the “spirit of gluttony” was upon her – a common tactic they used to guilt people into joining. My mom took the letter to my grandmother, who told her to burn it. “Nothing that upsets your spirit should be kept in the house,” she said. That evening, my mother placed the letter on our grill, lit a match, and set it ablaze.

The “spirit of gluttony” accusation leveled at my mother by a leader of Remnant Fellowship cannot be divorced from its historical lineage, both inside and outside of Christian churches. Pervasive cultural stereotypes like that of the Black mammy figure rely on the idea that Black people are gluttonous. Remnant Fellowship used that rhetoric to convince Black Americans they needed them, all the while making it clear that some bodies (usually not Black ones) are better, thinner, and more desirable. As author of Belly of the Beast: The Politics of Anti-Fatness as Anti-Blackness, Da’Shaun L Harrison, writes, “Pretty, Beauty, and Ugly are determined by the structures through which people are marginalized for their Blackness, their gender(lessness), and their bodies. Beauty standards, especially in the United States, are predicated on anti-blackness, anti-fatness, anti-disfiguredness, cisheterosexism, and ableism.” Remnant Fellowship tapped into anti-Black racism to proselytize Black Americans and to convince them they needed what Remnant Fellowship and Weigh Down Workshop had to offer.

***

As I reflect on my mother’s experience and on Twitter users condemning Helen Byrd and other Black Americans who joined Weigh Down Workshop, I am reminded once again of the lack of empathy that exists for fat Black women. In truth, the world of Weigh Down Workshop and Remnant Fellowship is indistinguishable from the anti-Black, anti-fat oppression that countless Black women, and other marginalized people, face on a daily basis.

By not unpacking the reasons for Black people’s experiences with Gwen Shamblin and Remnant Fellowship, the documentary opened Black interviewees like Byrd up to degradation instead of pointing out the constant surveillance and regulation of fat Black bodies that pervades our culture. Instead of questioning whether or not Black people should “know better” or enough to avoid these religious spaces, we should, instead, consider the conditions that make ripe our longings for social inclusion, for affirmations of bodies that are constantly critiqued, for worthiness. Our denigration has always been the active agent that solidifies the right(ous)ness of whiteness. When we orient ourselves from that viewpoint, it becomes clear the lengths to which some of us go in order to mitigate our suffering.

Ambre Dromgoole is a Ph.D. Candidate in the combined program in African American Studies and Religious Studies at Yale University. Her dissertation is tentatively titled “There’s a Heaven Somewhere’: Itinerancy, Intimacy, and Performance in the Lives of Gospel Blues Women, 1915-1983.”