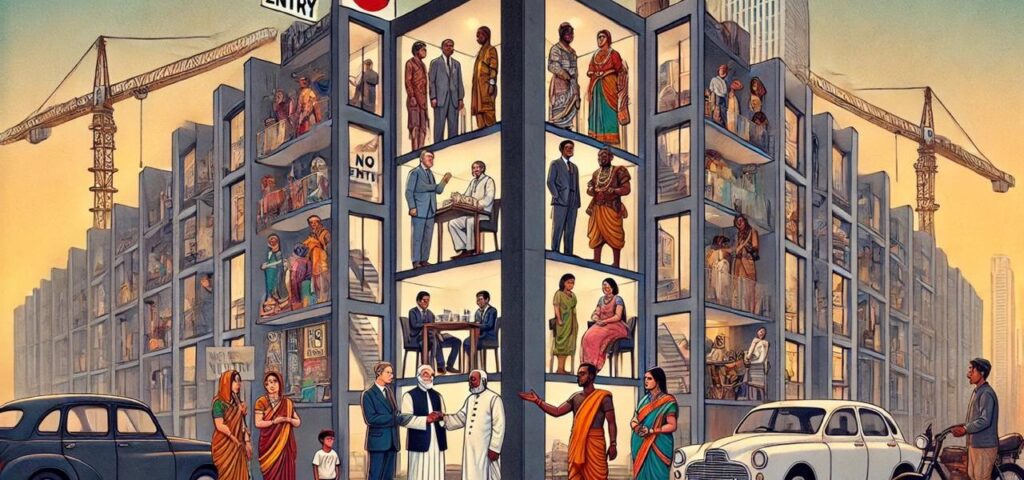

The Unwritten Rules of Renting in India for Queer People and Muslims

Navigating rampant discrimination in India’s rental housing market

(Image source: Michael Stravato for The New York Times)

For many in India, renting a home means answering more than just “How much can you pay?” It is about fitting into a landlord’s idea of an acceptable tenant. Akhil Katyal’s poem “Finding a House in Delhi” captures these barriers:

How many people will be staying?

We don’t rent to single people,

Only to families.

No, no, the landlord doesn’t interfere much,

Just no non-veg, no alcohol—

It’s a Jain building, after all, that’s only fair.

Oh, that’s a Muslim area—too congested,

Stacked one on top of the other.

Would you be okay living in a Muslim’s house?

Look, ground-floor flats aren’t easy to find.

This area is decent—full of Punjabis,

Well-ventilated, spacious.

No, no, bachelors create a nuisance—

Not you, of course, just saying in general.

Where are you from?

What do you do?

Your name?

No, your full name?

Bella, a 23-year-old trans woman in Delhi, has heard these questions before—not from a poem, but from brokers and landlords across the city. She recalls tirelessly roaming the city for weeks, trying desperately to find a decent place to live with her boyfriend. The broker, known for helping trans people find rentals, laid out the landlord’s strict conditions to Bella: “There shouldn’t be too much noise. No frequent visitors. Only a ‘decent’ way of living—no coming and going beyond what’s necessary.”

“The only thing I knew at that moment was that I needed to get this house. Whatever he asked for, I was ready to obey,” said Bella. While the landlord was willing to rent to Bella, he said he was going to charge her double the usual rate. “I told them that I do a respectable job, that I’m educated, and that I can speak English, so they agreed to give me the house.”

But living in the rented space for 4 years hasn’t been any less of a struggle for Bella. “There are days when my neighbors cut my electric wiring or dump garbage around my flat—when all I do is go to work, come back, and sleep, without causing anyone any trouble.” According to Bella, it’s their way of harassing her until she leaves the place.

Bella, who finds joy in dressing up and creating beauty, sees her flat as a stark contradiction—chaotic, unkempt, and nothing like the carefully curated world she carries within her. The only thing she connects with is a wall she has paneled with an entire mirror—for her love of dressing up. “My friends keep telling me, ‘Why don’t you decorate your place?’ But I can’t consider it my own. I don’t even know how much of me is reflected in this house or how much is hidden,” Bella says. “Maybe it’s the constant fear in my head that I could be evicted at any moment. Or maybe settling into this space feels like fooling myself into believing it’s home. I’m confused.”

Despite these constant negotiations, Bella is hesitant to start looking for another place, knowing all too well the struggles that come with finding a house—a process filled with endless rejections, as well as spoken and unspoken biases.

In India, the rental market is shaped through cultural and moral policing rather than legal frameworks. While housing discrimination is rampant, queer and trans individuals face an even tougher battle. With no legal safeguards against such biases, many are forced to hide their identities or accept precarious living conditions just to secure a roof over their heads.

Where cities promise solace to queer individuals—offering them both the anonymity and sense of communal belonging they seek—rental housing remains central to their lives, especially when returning to their families is not an option. Bella shares that while her family now accepts her as their daughter, the idea of going back home feels impossible. “Maybe I have freed myself so much that going back is no longer an option. Maybe I know that amidst all these struggles, I need to find my own place in this city.”

(Image source: Varsha Govil/The Caravan)

According to most studies, the LGBTQ community constitutes around 10% of India’s population—roughly 135 million people. Access to housing and a safe, secure living space is fundamental to living with dignity. Yet, for queer people, finding a safe place to live is often one of the hardest struggles. Many face various forms of violence within their own homes, including emotional and physical abuse, forced heterosexual marriages, “corrective” rape, house arrest, and withdrawal of financial support. When this violence becomes unbearable—sometimes even life-threatening—many queer and trans individuals are left with no choice but to leave their family homes. For them, rental housing is not just about having a roof over their heads; it is central to survival, autonomy, and self-expression.

The Transgender Persons (Protection of Rights) Act of 2019 prohibits discrimination against transgender people concerning their right to “reside, purchase, rent or otherwise occupy any property” in India. Yet, even in the open rental market, discrimination persists. Landlords and brokers impose arbitrary restrictions—refusing to rent to single tenants, demanding invasive personal details, or outright rejecting queer and trans applicants. Many are forced to conceal their identities, live in constant fear of eviction, or settle for unsafe accommodations in less desirable areas.

From Anti-Muslim Bias to Caste-based Prejudices

Discrimination in rental housing shapes Indian cities, demarcating which spaces are open or closed to certain citizens. According to a 2022 study, caste and religious identity play a crucial role in housing access, with Dalits (historically oppressed castes in India) and Muslims facing the worst discrimination in urban housing (the study did not account for barriers faced by LGBTQ individuals).

With the rising tide of anti-Muslim sentiment and the escalating atrocities against Dalit communities in India, the burden of concealing one’s identity—whether religious, caste-based, or gendered—has become an even greater challenge. Nowhere is this more evident than in the rental housing market, where discrimination operates through both explicit rejection and unspoken barriers.

Fahad (name changed), a 24-year-old cisgender gay man studying at a national university in Delhi, has faced these barriers firsthand. “I don’t know if being visibly affirmative about my sexuality makes a difference, but the primary reason I’ve been denied housing is because I am Muslim,” he said. “There are only certain clusters where Muslim people are even allowed to rent.”

Determined to live close to his university, Fahad didn’t hesitate to lie about his religion. His rental agreement is under his friend’s name, a necessary safeguard. “If our landlord finds out we’re gay, I don’t know how he will act,” he explained. “But if he discovers I’m Muslim, I wouldn’t be surprised if I’m thrown out on the street.”

Rituparna Bohra, 43, an Indigenous queer rights activist and founder of Nazariya, a queer feminist resource group, recalls the struggles of finding a rental house in Delhi. “In my early days, when I was searching for a home, I didn’t even have to reveal myself being queer—the first barrier was my Northeastern identity, which I couldn’t hide. I look a certain way, and landlords immediately assume that people from Northeast India will behave in a certain way. There’s this notion that we drink, stay out late, and that our food smells.”

“Discrimination is so rampant that, as migrants, we often seek solace in familiarity,” she adds. “That’s why you see Northeastern communities concentrated in certain urban villages or Muslims being ghettoized in specific parts of the city.”

A 2019 study by the Tata Institute of Social Sciences reinforces this reality. Among the LGBTQ individuals surveyed, none reported facing outright housing rejection explicitly based on their gender or sexuality—though this does not mean it wasn’t a factor. However, the study found that religion, particularly anti-Muslim bias, was the most commonly stated reason for rental refusals.

The Model Tenancy Act 2021 was enacted to regulate the formal rental housing market and protect the interests of landlords and tenants. However, it does not provide protection to tenants against discrimination and eviction on the grounds of caste, class, gender, or religious identity. This problem is further compounded by the structure of India’s rental housing market, where only 2% of urban rental agreements are formally registered. The vast majority of housing arrangements are informal—negotiated through brokers, landlords, and tenants in a space where contracts are verbally agreed upon, socially enforced, and offer little room for legal recourse. In such a system, discrimination isn’t just rampant—it’s institutionalized.

In India, there is no law that explicitly prohibits discrimination in the rental housing market. However, as a broker in Delhi’s most affluent neighborhoods explained, outright refusal based on religion or gender identity is not always direct. Since Muslims and many lower-caste communities are often associated with eating meat, landlords and brokers use food habits as a filter to exclude them without explicitly admitting to religious or caste-based bias. “You can’t simply say no to a Muslim or a trans person on their face—we live in a time where anything can go viral on social media,” he said. Instead, landlords and brokers have developed subtle mechanisms of exclusion. “If the client is Muslim, we bring the conversation down to food — ‘Do you eat veg or non-veg?’ Sometimes, the standard excuse that ‘bachelors aren’t allowed’ is enough to filter out unwanted tenants.”

Discrimination as Everyday Life

Simply having a roof over one’s head doesn’t guarantee a sense of belonging. Beyond securing a rental house, queer individuals often navigate daily life by misrepresenting themselves or their relationships just to blend in and to find safety.

Pinki (name changed), a 28-year-old trans woman from a basti, a slum, in Delhi, earns enough money to afford a decent flat. Yet, she chooses to stay in the basti for a simple reason: “It was the first place where I found shelter through another transgender friend when I arrived in Delhi. Even today, I don’t have to hide anything—what I do or who visits me—from the people here.”

While Pinki’s life has improved over the past decade, with a stable job at an NGO providing her with financial security, she has learned that respectability doesn’t always translate to dignity. “I once lived in a flat near my workplace in Kalkaji for three to four months, thinking I might finally live with peace. But I was constantly filtering myself.” The neighbors always seemed on guard—watching Pinki, questioning who came by the apartment. Pinki laughed as she remarked, “If I can’t even wear dark lipstick or drape a saree the way I want, what’s the point of living in such a flat? At least in the basti, people don’t see you as an outsider.”

Shubham Bose Roy, a queer graphic designer based in Delhi, has long sought a space where, like Pinki, they could simply exist without fear or scrutiny. In July 2016, they poured their frustration into a Facebook post:

“For the second time in the last two years, I lost my wallet last night while returning from a party in an auto—caught up in the chaotic process of camouflaging any signs of gender nonconformity to avoid attracting the attention of shady bikers who start following like bloodthirsty hounds. All the jewelry comes off. The handbag goes into a carry bag. The heels get replaced by slippers. Sexy dresses or stockings get covered by tees and pajamas. All because I live alone and can’t muster up the balls to challenge my neighborhood’s expectations of how I should look and behave like a man—especially my landlord”.

“It’s getting exhausting now. Can’t keep doing this. I need to find a place where the fact that I’m paying half my earnings for a physical space should be the end of the business deal—where my personal life is no one’s fucking entitlement.”

Aditi, a 27-year-old lesbian woman living with a trans man, shares: “We told our landlord that we’re a married couple, but the questions never stop. He often asks why my husband doesn’t have a deeper voice or why we don’t plan to have children. Neighbors drop by unannounced, casually prying into our lives—‘Why does your husband look so young?’ ‘Why doesn’t your husband work?’ I have learned to smile, nod, and deflect. Any sign of irritation could cost us our home, and we can’t afford to start over again.”

Yet this constant need to hide turns queer life in rental housing into a lie. Beyond the fear of being found out, the burden of constantly filtering one’s identity takes an unseen emotional toll. Even after securing a home, everyday life is shaped by what one can silently endure—and the hostility one cannot. Within this endurance lies the full weight of what is too often reduced to mere “discrimination.”

Passing, Paying, and Negotiating

Dhiren Borisa, a Dalit queer activist, poet, and scholar of urban sexual geography, reflects on his experience navigating the city’s rental market: “I was first introduced to a queer commune, and I can’t imagine how I would’ve accessed anything in the city without that. I was trying to secure a place through a broker, negotiating with one landlord after another. When I first started living alone on Hudson Lane, I remember the landlord constantly questioning me about marriage. ‘You’re this age and come from Rajasthan, a place known for early marriages. Why are you not married? What does your last name symbolize?’ But I could easily pass through such scrutiny.”

Borisa believes that this act of “passing” reveals the many ways some people manage to access the rental market. Borisa recalled, “One way I could pass was through my Ph.D. from a leading public university and the fact that I teach at another fancy private university. With these credentials, I could navigate the rental system, staying in the city without letting questions about my caste or last name dominate the conversation.”

Borisa recalls his most recent experience finding a rental house a year ago, when he was confronted with questions about his age and marital status. The broker, without consulting him, quickly responded to the landlord, saying, “He’ll be marrying soon, that’s why he’s looking for a house to settle in.” For Borisa, this felt like a lie—the broker had made a promise to the landlord that he would never fulfill.

Although Borisa is able to “pass” as straight, many others cannot or have no interest in trying. “What happens,” Borisa asks, “when gender nonconformity is hyper-visible, when queerness can’t be hidden within the language of passing in this heteronormative system? Or when your religion or caste is hard to conceal? People find themselves playing multiple roles just to survive. The real question is, how long does one survive?”

Bella, for example, shares that even though her landlord promised to be supportive of trans people, she still had to negotiate for a flat at a higher rent than usual. Similarly, for Pinki, the issue isn’t only how much she can pay, but rather: how much can she hide her non-normative identity in a world that demands conformity? This extends to situations like Aditi’s, where the real concern is whether she can afford to pick a fight with her neighbors or not.

Despite these entrenched barriers, there is little legal recourse for queer and trans individuals facing housing discrimination. While the courts have occasionally ruled in favor of LGBTQ rights—such as the decriminalization of homosexuality in 2018 and recent Supreme Court hearings on marriage equality—legal protections within housing remain largely unaddressed. Cultural shifts in urban spaces may offer some hope, but without explicit anti-discrimination laws in housing, queer and trans people will continue to navigate cities with precarity, forced to negotiate visibility, respectability, and survival in spaces that still refuse to make room for them.

Anuj Behal is an independent journalist and researcher focusing on issues of urban justice, gender, and migration in India.