The Ubiquity of Religious Appropriation

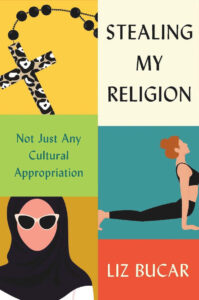

A review of Stealing My Religion: Not Just Any Cultural Appropriation

(Image source: Yoga Journal)

Over the last few years of the pandemic, as time both seemed to speed up and slow down, I started to mark the changing of the seasons by the holiday decorations displayed at my local grocery store. At some point during 2021, I began to notice a bizarre trend: leprechaun themed “yoga water,” an Easter Bunny in a yoga pose, a witch holding a sign that read “namaste,” turkeys meditating, and finally, a Christmas tree ornament shaped as a yoga mat with the word “yoga” painted on it in silver glitter for good measure. My partner got used to me buying these items, bringing them home, and lining them up on our dining table and studying them, like a mad scientist trying to crack a code.

These yoga-themed tchotchkes perplexed me. What was happening here? Who would be interested in buying these items? And perhaps most perplexing, how had yoga become tethered to U.S. and Christian seasonal products?

Recently, I brought this collection of trinkets to my undergraduate students and asked them to help me understand why people might buy, of all things, a figurine of an Easter Bunny doing yoga. In response, a heated debate ensued. One group of students felt strongly that this was disrespectful and an example of stealing the religious practices of Indians—that “commercializing” yoga in this way was inappropriate because it was an acute instance of “cultural appropriation.”

A separate and competing faction of students suggested that this sort of commercialism was “innocent,” especially since it was meant to be light-hearted and even humorous. These students argued that we should simply understand these items as a benign example of “cultural appreciation.” In fact, one student suggested that rather than read malintent into the production and consumption of these items, we should celebrate how yoga had become part of U.S. culture and its “melting pot.”

In truth, that conversation left me unsatisfied because, like many conversations about capitalism and culture in the U.S., the controversy seemed to center on whether or not adopting another community’s practices or objects, especially if associated with religion, was right or wrong. This sort of oversimplified right-or-wrong, innocent-or-guilty framing reflects a tendency to suggest that something is only harmful if or when there is an individual or group to whom we can assign blame.

Fortunately, Liz Bucar’s new book, Stealing My Religion: Not Just Any Cultural Appropriation, injects new life into what has become a stale discourse on the concept of “cultural appropriation.” Bringing together three disparate case studies, Bucar brilliantly demonstrates how definitions of religion fuse with practices of capitalism and ownership.

Fortunately, Liz Bucar’s new book, Stealing My Religion: Not Just Any Cultural Appropriation, injects new life into what has become a stale discourse on the concept of “cultural appropriation.” Bringing together three disparate case studies, Bucar brilliantly demonstrates how definitions of religion fuse with practices of capitalism and ownership.

In the introduction, Bucar explains what she means by appropriation, especially religious appropriation. “Religious appropriation,” she writes, is “when individuals adopt religious practices without committing to religious doctrines, ethical values, systems of authority, or institutions, in ways that exacerbate existing systems of structural injustice.” By considering the way religious appropriation both creates and sustains forms of inequity, Bucar offers a compelling critique of secular liberalism, arguing that the “right to life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness” excuses and perhaps even encourages acts of exploitation since secular liberalism suggests that everything should be available to everyone, even if it means usurping others’ cultures and religious traditions.

To support her claim, the first chapter explores how progressive political movements, like feminism, can perpetuate inequity through religious appropriation. Bucar examines the consequences when non-Muslim women have worn the hijab to show allyship with Muslim women. Bucar shows how, despite its good intentions, the adoption of the hijab as a political statement among non-Muslim women produces unintended consequences. For example, Bucar illuminates how white feminists in the U.S. failed to consider that their adoption of hijab could reinforce the false idea that all Muslim women wear veils. Highlighting the critiques of “solidarity hijab” that emerged from the Muslim community, Bucar explores how “some Muslim women experienced these well-meaning acts as exploitation…[and that] these expressions of liberal inclusion did not always have the effect of supporting Muslim women. In fact, just the opposite: in some cases, solidarity hijab contributed to the further racialization and subjugation of Muslim women.”

(Image source: dailysabah.com)

In the second chapter, “Playing Pilgrim,” Bucar explores the collision of U.S. evangelical Christianity, heritage tourism, and study abroad programs. Based on ethnographic research conducted with a study abroad program Bucar developed and led for years, the chapter focuses on the Catholic pilgrimage route in Spain known as the Camino de Santiago.

While the entire book is engaging, I must admit that this chapter has stayed with me for its insights on evangelical Christianity. The chapter explores how certain varieties of evangelical Protestants position themselves as superior and more righteous Christians than all others. Bucar shares how her evangelical Christian students engaged with the Camino as a Catholic practice, and behaved as though it was at odds with and ultimately inferior to their own belief systems. According to Bucar these students exhibited a sense of superiority when confronted with Catholic beliefs and practices on the Camino, revealing a kind of self-feeding narcissism among evangelical Protestants. Ultimately, Bucar’s analysis uncovers how evangelical Christianity fuses with white supremacy in terrifying ways, to this reader at least.

The third chapter focuses on Bucar’s time receiving teacher training at a Kripalu yoga retreat. The Kripalu center where Bucar underwent 200 hours of yoga training is one of the oldest in the United States. Through analysis of her time there, Bucar offers a deeply sensitive perspective of the somewhat common critique today that practicing yoga represents a form of cultural appropriation, especially among white Americans.

After a brief but thorough historical overview on how yoga emerged as a consumer wellness practice in the United States, the chapter explores the complex and at times contradictory ways individuals experience yoga as a spiritual practice. Bucar cleverly dubs the style of yoga common today “respite yoga,” which she defines as a form of yoga intended “to reduce stress and achieve well-being…marketed as vaguely spiritual and yet requires no religious commitments, making it accessible to everyone.” Bucar goes on to clarify:

“Respite yoga relies on practices, including physical postures, borrowed from devotional yoga, as a way to present itself as ancient, mystical, and powerful, but often without the larger systems of thought and belief they developed from, such as ethics and cosmologies. But modern respite yoga also adds new things to the mix to make the practice seem more ‘authentic,’ including the opening and closing of a class with namaste as a form of pseudo- liturgy. In other words, respite yoga depends on the appropriation of devotional yoga. It is just as much an invention of something new as the practice of something old.”

Bucar convincingly argues that respite yoga, as it is currently practiced, is a form of religious appropriation. In making this argument, however, Bucar deftly avoids indicting or absolving the people who practice yoga. Rather, her exploration of respite yoga’s success in the United States demonstrates how it operates as a direct byproduct of the formation of an Indian and majority Hindu nation-state after the fall of the British Empire and the new nation’s desire to export some of its traditions abroad.

The book concludes by zooming back out and connecting the three case studies to each other. Bucar weaves the case studies together to question how it might be possible to borrow from religious traditions responsibly and in ways that do not contribute to reinforcing social hierarchies.

To this reader, Stealing My Religion accomplishes what it sets out to do and then some. Bucar takes on a messy and often alienating topic – how we understand and make room for critical understandings of, and conversations about, religion in society. Bucar’s book helped me understand why, for example, the yoga seasonal trinkets in my grocery store exist and why people might want to buy them. She does so by explaining how common appropriation has become in our capitalist world, and how it, “relies on and contributes to existing forms of structural injustice.” Moreover, she shines a bright if uncomfortable light on how, as U.S. Americans, we are inured to this mechanism because most of us experience and consume appropriation as culture. Put another way, those yoga tchotchkes exist and might even sell because they meld symbols of white U.S. Christianity with Hinduism in a way that still keeps majoritarian Christian holidays at the center of how we organize time and our shared lives as members of a society.

Ultimately, Bucar imparts to her readers a clear and unsettling awareness of how fundamental religious appropriation is to U.S. forms of liberalism. And she offers us a path forward, reminding her readers in her conclusion that we can and should resist normalizing these sorts of everyday harms: “the ability to say ‘No, I shouldn’t do this [or buy this or support this] even though I know I can’ is a powerful acknowledgement of personal privilege and a commitment to not allowing inherited entitlement to continue unchecked.”

Rumya S. Putcha is an assistant professor of music and women’s studies at the University of Georgia. Her first book, The Dancer’s Voice: Performance and Womanhood in Transnational India (Duke University Press), will be released in December 2022. Her next book, Namaste Nation: Orientalism and Yoga in the 21st Century, explores how ideas of health are performed as public expressions of identity.