The Trump Era’s Tribalism Discourse: Reflections on a "Weird Euphemism"

Why are politicians and pundits describing the current political climate as one marked by "tribalism"?

Image by Joe Penny

Now at the midpoint—or the near-end, or perhaps the just-beginning—of what we’ll call the Trump Era, we can begin to reflect on the various explanations offered, some already discarded, of “what the hell is going on.” Explanations for what is happening vary, of course, depending on what one thinks is happening. While many have critiqued Donald Trump and his administration for their policies, ineffectual leadership, racism, and sexism, as well as admonishing the Republican Party for enabling and supporting the Trump agenda, other observers have pointed to something more widespread and cultural. Trump, for them, is a symptom more than a cause (but also a cause) of political polarization and social fracture. This group of politicians and political thinkers, mostly but not exclusively on the right and center-right, has been troubled by a litany of concerns: Trump’s vulgarity, the incivility of his more vocal supporters, an increasingly visible activist left, campus protests, and the overwhelming sense that we all cannot, in fact, just get along. For these maladies, they have offered a diagnosis: tribalism.

Tribalism, according to these critics, is a root cause that leads to polarization, partisanship, and “identity politics.” As liberal pluralism cracked up, sometime toward the end of the Obama presidency, we splintered (back) into “tribes.” The people of the United States, at cultural, social, and political levels, are devolving, sliding back into their primitive nature. Conservative writers David Brooks, Andrew Sullivan, and Jonah Goldberg; journalists Robert Wright and David Roberts; law professor and author Amy Chua; U.S. Senators Jeff Flake and Ben Sasse; and many more—they all found “tribalism” to be a compelling explanation for political division, factionalism, and incivility.

For these pundits who use the term, “tribalism” comes with a mentality of “identity politics” that pits smaller identity-based groups against each other and against a broadly inclusive and “colorblind” U.S. civil society. For these critics, evidence of tribalism can be found in examples as wide-ranging as the Black Lives Matter movement, surging white nationalism, and rancor between Senators of different parties. Political scientist Francis Fukuyama suggested, “Perhaps the worst thing about left-wing identity politics is that it has stimulated the rise of right-wing identity politics.” In some cases, such commenters bought the argument that white nationalists were simply responding to the overreaches from the left. In recent months, tribalism has been accused of helping spread COVID-19 and killing political liberalism. These works, taken together, make up what I’m calling the tribalism discourse, a popular brand of writing and thinking that uses “tribalism” as both a description and explanation for the cultural politics of the Trump Era.

But why this word? What is it about “tribalism” that seems to have explanatory power to so many popular writers and politicians?

***

The tribalism discourse reveals the anxieties of a tenuously secular age. Amid “fake news,” “media silos,” and unending lies and obfuscation at White House press conferences, some critics have warned that we are in a post-truth era. Objective truth, trust in science, the public sphere, and liberal democracy feel brittle, already cracked and crumbling. Sober reason, the hallmark of Enlightenment modernity, has given way to premodern, fanatical factionalism. Writer David Roberts connects post-truth and tribalism through what he calls “tribal epistemology.” In this way of thinking, people assess information not according to established and widely agreed-upon public standards of objective truth but, instead, according to whether it benefits the “tribe.” “‘Good for our side’ and ‘true’ begin to blur into one,” Roberts writes. If this is the case, then the accomplishments of the Enlightenment, the achievements of a secular age, feel fragile indeed.

Secularization theories posit a progression from the primitive to the enlightened. Secularization narratives describe a society’s advancement from religion to non-religion, or from primitive bad religions to enlightened good religions (the best and most enlightened being no religion and/or liberal Protestantism). But secular, modern people define their own secularity by contrasting it with the insufficiently secular, often in racializing terms: the superstitious, credulous, primitive, fanatical, and the tribal.

Purveyors of the tribalism discourse delineate good politics from bad. Good politics is pluralistic, egalitarian, and civil. Bad politics is factional, identity-based, and uncivil. To be tribal, in this discourse, is to do politics wrong by treating politics like a religion. Much has been made in recent years of the way that social life is increasingly organized around political identity, or how seemingly unrelated facts of age or geography—one’s proximity to a Cracker Barrel or a Whole Foods, for example—can predict voting patterns. There is a lot to say about “why we’re polarized,” and many ways to theorize, conceptualize, and explain these aspects of our contemporary political and cultural moment. But “tribalism”—this “weird euphemism,” as writer Adam Serwer put it—accomplishes something other terms and frameworks don’t, and that is because it folds in a racialized secularization narrative.

***

The label “tribal” has a distinctly colonialist history as a pejorative term imperialists used to rule over the people whose land they colonized. The Trump-Era tribalism discourse keeps this legacy alive. Jonah Goldberg, a writer for the conservative National Review, explains in his 2018 book Suicide of the West, “When we fail to properly civilize people, human nature rushes in. Absent a higher alternative, human nature drives us to make sense of the world on its own instinctual terms: That’s tribalism.” By Goldberg’s account, it is natural to be tribal, so the liberating forces of modernity—liberalism and capitalism—are a “Miracle,” allowing fallible humans to transcend their instinctual natures and make something better. But who is the we in “When we fail to properly civilize people…”?

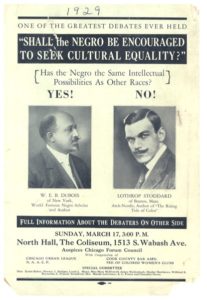

The current tribalism discourse is new, but its frameworks are not. One hundred years ago, in his landmark treatise The Rising Tide of Color Against White World-Supremacy, the famed white supremacist scholar Lothrop Stoddard wrote, “Wherever the white man goes he attempts to impose the bases of his ordered civilization. He puts down tribal war, he wages truceless combat against epidemic disease, and he so improves communications that augmented and better distributed food-supplies minimize the blight of famine…” Stoddard was articulating a theory of whiteness as property, as a justification for colonialism as enactment of rightful ownership, made rightful through the forces of technological civilization over the instincts of tribalism. That same year, 1920, famed Black scholar W.E.B. Du Bois defined whiteness as “the ownership of the earth forever and ever, Amen!” (Du Bois and Stoddard later had a much-publicized debate; Du Bois won.) Of course, not all critics of tribalism are white supremacists, but whiteness works by obscuring its particularity and pretending to universality, rationality, and the normal. And the secularist tribalism discourse works similarly, to separate the irrational tribalist from rational democratic citizen, marking the former as particular and the latter as universal.

The current tribalism discourse is new, but its frameworks are not. One hundred years ago, in his landmark treatise The Rising Tide of Color Against White World-Supremacy, the famed white supremacist scholar Lothrop Stoddard wrote, “Wherever the white man goes he attempts to impose the bases of his ordered civilization. He puts down tribal war, he wages truceless combat against epidemic disease, and he so improves communications that augmented and better distributed food-supplies minimize the blight of famine…” Stoddard was articulating a theory of whiteness as property, as a justification for colonialism as enactment of rightful ownership, made rightful through the forces of technological civilization over the instincts of tribalism. That same year, 1920, famed Black scholar W.E.B. Du Bois defined whiteness as “the ownership of the earth forever and ever, Amen!” (Du Bois and Stoddard later had a much-publicized debate; Du Bois won.) Of course, not all critics of tribalism are white supremacists, but whiteness works by obscuring its particularity and pretending to universality, rationality, and the normal. And the secularist tribalism discourse works similarly, to separate the irrational tribalist from rational democratic citizen, marking the former as particular and the latter as universal.

***

Journalists and politicians who participate in the tribalism discourse believe that tribalism is bad, and that it has reached a high point in the Trump Era, but they also often believe that tribalism is inescapable because it is universal. Human nature itself is tribal. Humans naturally divide into groups and make enemies. This idea is central to most writing on tribalism, and it structures an evolutionary secularization story. The Yale Law professor and popular author Amy Chua, in her 2018 book Political Tribes, argues that what makes America great is its unnatural and unusual supersession of our tribal nature. The book rests on the premise that the United States is a “super group,” made up of different cultures and organized by ideas and politics rather than ethnic or racial or religious factions. This super group is organized by “the great Enlightenment principles of modernity—liberalism, secularism, rationality, equality, free markets.” However, Chua cautions, these principles “do not provide the kind of tribal identity that human beings crave and have always craved.” Like Goldberg, Chua recognizes how tenuous being modern can be. Other countries haven’t achieved it, and Americans fail when we expect them to. “We tend to assume that other nations can handle diversity as we have, and that a strong national identity will overcome more primal group divisions.” This misguided optimism, according to Chua, has led to many geopolitical problems, including the fallout of the Iraq War as Americans failed to recognize the depths of Iraqis’ tribalism. At the heart of Chua’s narrative is a sort of evolutionary, perhaps even eugenic, American exceptionalism. The United States has achieved something special and unnatural, evolving out of our primitive natures and escaping the group instinct that pulls back other cultures and countries.

It is for this reason, our dangerously primal drives, that “America wasn’t built for humans,” according to writer Andrew Sullivan. To be tribal is so easy, so natural, so human. Journalist Sebastian Junger offers the following anecdote in his 2016 book Tribe: Benjamin Franklin noted that so many white people joined Native American communities but so few Native Americans, so far as he could tell, seemed interested in converting to Christianity and fully joining “civilization.” Goldberg borrows this story and elucidates the problem: “Why? Because there is something deeply seductive about tribal life. The Western way takes a lot of work.” Civilization, like modernity, must be maintained. Goldberg warns that the natives’ ways of life are seductive, and if we don’t civilize them, they’ll tribalize us, bringing out those base group instincts now suppressed but intrinsic to fallen humanity.

***

The tribalism discourse offers not so much an explanation as an ideological assertion. Chua’s book chapter on inequality and tribalism in the U.S.—which includes the topic sentence “America’s underclasses are intensely tribal”—shows the diminishing returns on this idea’s explanatory power. “Tribalism” applies so widely, so pervasively, that it isn’t clear what it illuminates. The American tribalists include gangs, NASCAR fans, WWE fans, and America’s “two white tribes” (Trump supporters and “coastal elites”). Bad religions, like the prosperity gospel and “narco-saints” (devotees of Santa Muerte), are tribal too. Tribalism is not just for the “underclasses,” though, and it can be found on both sides of the political aisle. Chua writes, “The Left believes that right-wing tribalism—bigotry, racism—is tearing the country apart. The Right believes that left-wing tribalism—identity politics, political correctness—is tearing the country apart. They are both right.” For Chua, it is natural and even good to be a little tribal, to root for your favorite sports team, make strategic alliances, or support your family members. But it’s easy to take it too far and be uncivil and unduly partisan, and that, she argues, is the problem with the U.S. today. And only robust pluralistic nationalism can overcome tribalism and make America a “super group” again.

Perhaps so many writers have been drawn to the tribalism discourse because it has the air of explanation without the rigor of research. In confusing times, tidy answers can offer comfort (and book deals). Indeed, the whole point of the tribalism discourse, it seems, is to assure readers that they are modern, not tribal, by identifying the credulous other. Permit me one more example from Chua’s book. In a dismissive passage on sovereign citizen movements (groups who believe they not subject to the laws of the United States because they are members of alternative polities and/or subject to higher laws), Chua assures, “As absurd as [their] beliefs sound, the psychological appeal of the movement is easy to understand.” The Washitaw Nation, for instance, which Chua describes with derision and sarcasm, is in fact not easy to understand. They have a complex history and complicated ideas. But tribalists exist outside of history, as stagnating pagans captive to timeless group psychology. Tribalism is supposed to be ever-present and, at the same time, relegated to the past.

Perhaps so many writers have been drawn to the tribalism discourse because it has the air of explanation without the rigor of research. In confusing times, tidy answers can offer comfort (and book deals). Indeed, the whole point of the tribalism discourse, it seems, is to assure readers that they are modern, not tribal, by identifying the credulous other. Permit me one more example from Chua’s book. In a dismissive passage on sovereign citizen movements (groups who believe they not subject to the laws of the United States because they are members of alternative polities and/or subject to higher laws), Chua assures, “As absurd as [their] beliefs sound, the psychological appeal of the movement is easy to understand.” The Washitaw Nation, for instance, which Chua describes with derision and sarcasm, is in fact not easy to understand. They have a complex history and complicated ideas. But tribalists exist outside of history, as stagnating pagans captive to timeless group psychology. Tribalism is supposed to be ever-present and, at the same time, relegated to the past.

The Trump Era is not the first time that “tribes” have featured in a secularization story. In his landmark 1965 book The Secular City, Harvey Cox theorized, “Tribal man is hardly a personal ‘self’ in our modern sense of the word. He does not so much live in a tribe; the tribe lives in him.” The modern subject is a self-possessed individual—“a sovereign, self-owning agent,” as Talal Asad put it. The tribal subject, conversely, is owned by the collective. In the modern world, that’s no way to do politics or religion. Secularism is a political ideology that defines the modern as nonsectarian, public, and above all rational.

And it’s that aspect of the tribalism discourse—the racialized project of liberal secularism—that terms like “polarization” or “fracture” don’t quite invoke. It’s one thing to say that politics these days has gotten divisive and nasty, or to worry about how closely people’s various identities are aligned with their political affiliations. But it’s another to blame these conditions on primitive human nature that some people have transcended, while others slip back into a less evolved stage of the race. That’s what made “tribalism” such a handy framework: a deep colonialist logic that gestures toward universal human nature while ever reassuring the reader who the real moderns are. After all, modernity was always about “us” and “them.”

Charles McCrary is a postdoctoral fellow at the John C. Danforth Center on Religion and Politics at Washington University in St. Louis. His book Sincerely Held: American Religion, Secularism, and Belief is under contract with the University of Chicago Press.