The Solution is Jesus: Christian Nationalism from Brazil to the United States

Democracy’s undoing and global Christian nationalisms in “Apocalypse in the Tropics”

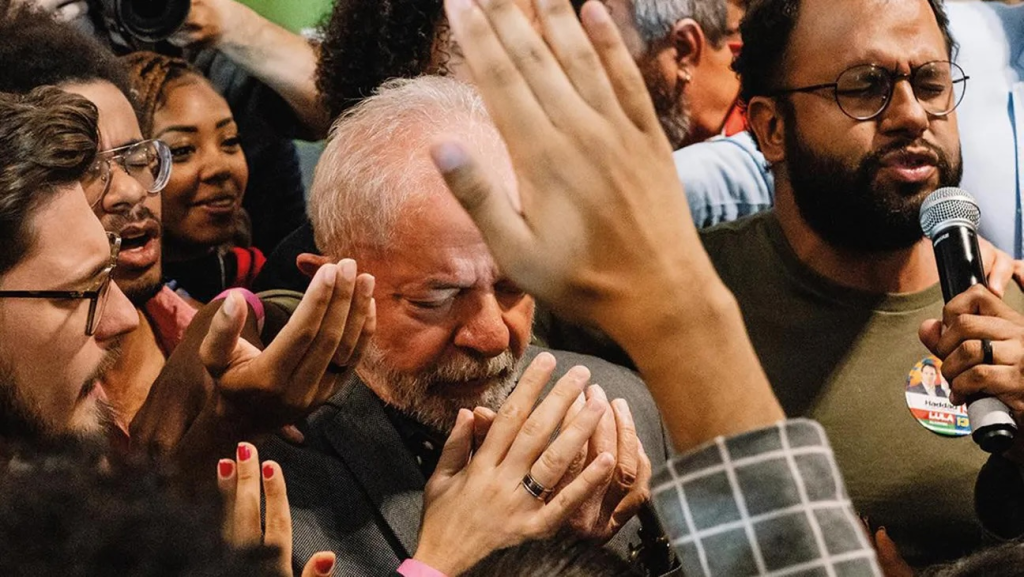

(A scene from the documentary Apocalypse in the Tropics. Source: The Hollywood Reporter)

Halfway through Brazilian filmmaker Petra Costa’s documentary Apocalypse in the Tropics, released on Netflix in July 2025, one of the most influential evangelical pastors in Brazil sketches his vision of democracy. The pastor, Silas Malafaia, says that for too long decisions have been made by powerful interest groups, which has left the majority behind. Democracy should be simple: “It’s the right to say what you want and the people to judge and say, ‘I don’t want this guy because I don’t support that.’”

Costa disagrees, and asserts that democracy also implies the protection of minority rights, not domination of the majority at all costs. Costa has been tracking the erosion of such rights—the protection of Indigenous Brazilians’ land against logging, the ability to protest against the government without retribution—since her previous film, The Edge of Democracy. For her, the goal of Brazil’s Constitution and federal structure is the protection against the majority from steamrolling racial, religious, political, and sexual minorities, as happened during Brazil’s military dictatorship from the 1960s to 1980s.

But Malafaia, who is a confidante of Jair Bolsonaro, the former president now under house arrest for staging a coup, is having none of it. “Democracy is the absolute majority’s will!” he shoots back.

This attitude, which Costa says is widely held by evangelicals in Brazil, is precisely why Costa sees Christian nationalism as a grave threat to Brazilian pluralism. Democracies emerged, Costa argues, with the overthrow of kings who claimed the divine right to rule. But now, she says, Brazil is heading in the “opposite direction,” with Christian nationalists attempting to install religious leaders at the levers of state power and use God as a cudgel, eschewing the duty of democracies to protect the vulnerable.

The documentary traces the emergence of Christian nationalism in Brazil as a political and religious force between the rule of former right-wing president Jair Bolsonaro and the 2023 re-election of leftist Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva (known simply as Lula). The context for this moment is the dramatic rise of evangelicalism in the country from 6.5% of the population in 1980 to over 25% in 2022. This rapid increase makes Brazil one of the countries with the highest growth of evangelicalism in the world, which observers trace to aggressive missionary work in remote places, evangelicals’ savvy use of media, and a multiracial coalition that has focused recruitment efforts on marginalized segments of Brazilian society.

The documentary traces the emergence of Christian nationalism in Brazil as a political and religious force between the rule of former right-wing president Jair Bolsonaro and the 2023 re-election of leftist Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva (known simply as Lula). The context for this moment is the dramatic rise of evangelicalism in the country from 6.5% of the population in 1980 to over 25% in 2022. This rapid increase makes Brazil one of the countries with the highest growth of evangelicalism in the world, which observers trace to aggressive missionary work in remote places, evangelicals’ savvy use of media, and a multiracial coalition that has focused recruitment efforts on marginalized segments of Brazilian society.

Behind evangelicalism’s popularity is a willingness among churches and religious leaders to involve themselves explicitly in politics, using blueprints for political action drawn up by U.S. pastors like Billy Graham and Jerry Falwell. For too long, Malafaia says, churches in Brazil—specifically the Catholic Church—emphasized that Christians were “only citizens of heaven.” But in a sermon to his flock, we see him encouraging his congregation to make a difference “in education, in entertainment, in culture, in science, in the arts, in business, in commerce, in the Executive, in the Legislative, in the Judiciary.” It is this comfort with eliding the distinctions between church, state, and civil society that Costa sees as a prime example of Christian nationalist thought.

With close access to many of the major players in Brazilian politics and evangelicalism, including the two major presidential candidates themselves, Costa navigates what she sees as a turning point in the role of religion in government as narrated by those at the front lines of the battle. Her work is both a warning to others and a eulogy for societal values that she felt were more widely shared and now sees being discarded—protections of minority rights, respect for governmental institutions, and the concept of a secular democracy. Costa strikes this elegiac tone while self-consciously showing how Brazil’s experience with Christian nationalism resonates strongly with that of the United States.

It’s in the U.S. context that I work as an anthropologist, researching Christianity, right-wing politics, and the specific amalgamation of the two that could be called Christian nationalism. Like Costa, I see parallels between the United States and Brazil. This past summer, I visited a church in Western Kentucky where congregants recited the Pledge of Allegiance before the sermon and the head pastor warned us that the service was for those who “love America.” He continued to say, “They decided that it’s legal to burn the flag, but I wouldn’t recommend doing that here.” There were more bald eagles and stars and stripes inside the church than crosses.

But that kind of outward alignment between Christianity and U.S. national symbols is more the exception than the rule. It is tricky to unpack the various strands of the global religious right across traditional churches, new charismatic movements, and those non-religious leaders such as President Trump who may serve as convenient allies for religious nationalist projects. At the recent public memorial service for conservative Christian podcaster Charlie Kirk, for instance, there were speakers who explicitly called on a Christian government in the United States, while others—such as Homeland Security Advisor and Deputy White House Chief of Staff Stephen Miller, who is Jewish—stood alongside these voices with an irreligious battle cry to defend civilization against forces of darkness. That lack of cohesion within the right makes understanding Christian nationalism as a separable or unified movement a difficult task.

A similar messiness exists in Brazil, but Costa’s film fails to distinguish between evangelicals as a whole, Christian nationalists, and populist right-wingers in a slippage that makes assigning blame for the backsliding of Brazilian democracy only to Christian nationalists too simplistic. The Brazilian right—as the film itself shows us—is just as internally incoherent, outlandish, and frightening as the U.S. one.

And that’s not a coincidence: many in the Brazilian right have modeled their movement on the United States and speak directly about and to it. At Bolsonaro rallies in the documentary, large signs read “We Support President Bolsonaro” in English; there has been an increased use of U.S. flags as symbols of the right; and the storming of the federal complex (known as the Praça dos Três Poderes, or Plaza of the Three Branches) on January 8, 2023, was inspired directly by the storming of the U.S. Capitol on January 6, 2021—there was even a green-and-yellow version of the infamous “QAnon Shaman” present.

One way we could understand this unity between such different groups is through what Costa calls “a real or imagined sense of embattlement.” Malafaia, the Brazilian pastor, preaches about how those who don’t support gay marriage or other socially progressive ideas are made to feel like outsiders. Others in the film echo this idea of feeling like the “real” majority has been silenced in favor of undeserving or scheming others. This feeling combines with Malafaia’s populist conception of democracy—wherein the majority has absolute power—to animate his insistence that Christians and the right are being persecuted and represent the authentic will of the Brazilian people.

This feeling of vulnerability as Christians has come up again and again in my own research. One pastor explained to me that he saw the United States as “anti-Christian.” Many others see the signs of their societal exclusion in culture war issues or mass media. The idea is so prevalent that conservative Christian writer Aaron Renn coined the term “negative world” to index the contemporary moment of hostility towards Christians. It was surprising to me the first time I heard this line of argument—how could Christians really think, under the aegis of the second Trump administration where Christian fundamentalists seem closer to effecting their vision within the halls of power than ever before, that they were the ones being persecuted?

Part of the answer resonates with how other powerful majorities have made similar claims. White supremacist ideology, for one, relies on a similar sense of victimhood that paints whites not as oppressors but subject to the efforts of racialized others to replace them or even commit “white genocide.” Religious, ethnic, and national majorities use the rhetoric of victimhood from India to Israel to England, so much so that some scholars have suggested the term victimhood nationalism to draw together these distinct movements. Only if these majorities wake up and fight, the advocates of this perspective suggest, will they secure a future against the efforts of minorities, often seen to be working in league with shadowy forces of evil—“globalists,” “cultural Marxism,” or “wokeness.” Across very different geographic contexts, these arguments hold sway and animate exclusionary political projects. It is often difficult to disaggregate exactly who these movements see as enemies—and just as difficult, sometimes, to identify who is being identified as being part of the authentic majority. But claims of victimhood have clear political appeal and power despite—or because of—this ambiguity.

Part of the sense of embattlement among Brazilian evangelicals that Costa tracks, then, is emotionally-driven and even conspiratorial. Nonetheless, Costa makes the excellent observation early in the film that many who are part of the new evangelical movement in Brazil have been ignored or left behind in various ways—through the poverty wrecked by neoliberal economic policies to a lack of infrastructure in rural areas. The popularity of the movement is not an organic “anti-woke” backlash on solely cultural terms, long awaited by parts of the right. Instead, Costa is attentive to how evangelicals in Brazil have spread their message by taking the material needs of their congregants seriously. This is another part of the answer to the puzzle of victimhood that we must consider.

The Catholic Church in Brazil, she argues, long ago abdicated its role to address the material conditions of the poor. In its place stepped evangelical missionaries, many of them at first from the United States and later Brazilian converts, who emphasized both spiritual and material remedies to sickness, depression, and hunger. “In any remote city of Brazil, where there is no hospital, no paved roads,” Costa narrates, “there is always an evangelical church.” In villages throughout the country where there are few government services, the gospel—and food, medicine, and other supplies—arrives by boat.

In rural Kentucky, where my research is based, churches have similarly stepped into roles vacated by the government. Churches are the central node of communal life, especially in rural areas. Congregants consistently mention how their churches have supported them in troubled times as reasons they feel welcomed, from donations for hospital stays to weekend barbecues to emotional support. Many churches run or support independent efforts to provide social services, including food banks and residential programs for adults with developmental disabilities.

Other efforts happen in tandem with federal, state, or local government ones, such as rapid response to the increasing number of natural disasters likely exacerbated by climate change. In 2021, western Kentucky experienced the deadliest tornado in the U.S. in ten years, with several small towns leveled and over fifty people killed. Just this past April, historic amounts of rainfall led the Ohio River to overflow its banks in the city of Paducah, and extreme heat during summers has led to multiple deaths. In addition, the everyday disasters of cuts to social services such as food stamps, public housing, and Medicare—approved by politicians supported by many in the communities in which I work—have made life increasingly precarious in terms of hunger, homelessness, and illness. In the aftermath of these crises, churches and religious organizations see their work as both addressing the material harms as well as proselytizing to “unchurched” people, who may otherwise be inaccessible to pastors keen on spreading God’s word. Disasters “open the door to the gospel,” Ron Crow, leader of Kentucky Baptist Convention Disaster Relief, told me during an interview this summer.

One need not buy into the corrosive rhetoric of some Christian nationalists such as Malafaia that Christians are the sole victims of modern democracies to recognize that the narrative of embattlement is not wrong so much as it is incomplete. I do not mean to reduce the spread of evangelicalism to only economic factors, suggesting simplistically that churches create themselves as pseudo-states in the absence of political governments. Belief, emotion, and belonging play a role as well. But those of us who believe in secular states and democratic politics ignore material conditions and the failures of democracy for the poor at our own risk. As with so many oppressed by our supposedly “free” democratic system on racial, gender, and class grounds, invocations to the higher ideals of democracy are not compelling if they just mean arguing for a continuation of the status quo.

Lula, Bolsonaro’s opponent, attempted to chart a path forward for the left in his 2023 campaign that took the power of religion seriously. He tells a story to Costa late in the documentary: a worker loses his job and goes first to the union. The union says he needs to organize and strike, and the worker emerges disappointed: “I lost my job and this guy wants me to start a revolution.” So he goes to the Catholic Church, where the priest tells him not to worry, that the Kingdom of God in heaven is for the poor. Finally, he goes to an evangelical church, which tells him simply: “The problem is the Devil and the solution is Jesus.” Finally, someone gives him a solution.

Lula managed a slim victory in the 2023 election, but Costa argues that the threat of Christian nationalism remains strong. The documentary ends in the aftermath of the attack on the federal compound in January 2023. Brazil is facing a crisis of apocalyptic proportions, Costa says—even as her ideas of apocalypse are different from those of many evangelicals from whose language she borrows.

As the camera tracks through the shattered windows of the Praça dos Três Poderes and damaged busts of past Brazilian leaders, Costa tells us that Brazil is at risk of losing its status as a secular democracy despite the respite of Lula’s victory. Perhaps, she implies, the backlash to the victory will be even more ferocious—like it was in the U.S., with conspiratorial thinking, Christian nationalism, and white supremacy taking center stage within Trump 2.0. She says via voiceover that perhaps a “future apocalypse can reveal” that the halls were “built to protect what is vulnerable.”

Costa is right that protecting the vulnerable is the core of our democratic prerogative. And we must be wary of how that sense of vulnerability can be co-opted by populist and majoritarian movements.

But we should not let this feeling begin and end with mourning and fear. Many citizens of supposedly democratic societies such as the U.S. and Brazil have long viewed democratic institutions and traditions—from elections to secularism to the symbols of power such as those in the U.S. Capitol or Praça dos Três Poderes—as window-dressing, obscuring the real mechanisms of power and corruption that play out behind the scenes. There are powerful, malicious actors who exploit this distrust—preachers, politicians, and populists—but the response ought not simply be to proclaim the value of such institutions in an automatic way, as if we are all in agreement about the value of democratic ideals that have served some of us better than others. Instead, we must consider what a politics that actually does protect and serve the vulnerable may look like.

The Christian right has found a way to attend to both the material and transcendent: feeding, healing, and crafting compelling narratives of the world. The left—and any who care about those ideals of democracy, of protecting the vulnerable that Costa and many others espouse—must attempt the same.

Liam Greenwell is a Ph.D. student in the Department of Anthropology at Cornell University. His research focuses on evangelicalism in the United States, whiteness and racial identity formation, and right-wing politics.