The “Slave Bible” is Not What You Think

The Museum of the Bible presented misleading information to attract people of color to the museum

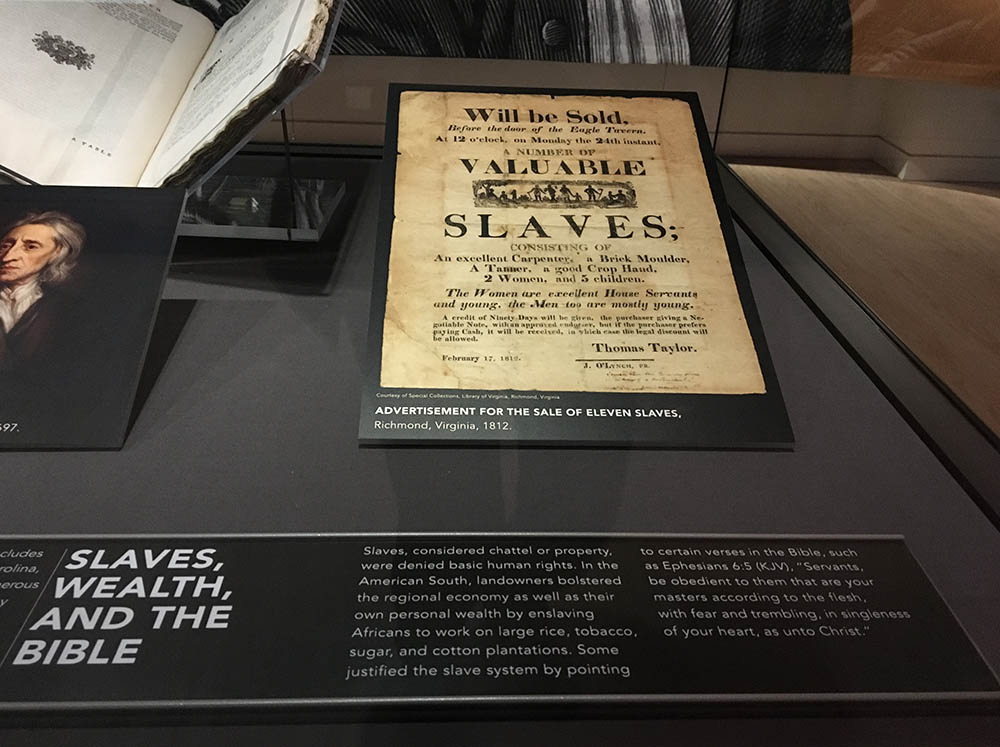

“Slave Bible” exhibit at the Museum of the Bible

We need to have a hard conversation. The “Slave Bible” is not a Bible—even if the Museum of the Bible tells me so.

In the first couple years of its tenure near the national mall, the privately-funded Museum of the Bible (MOTB) has worked its public relations team in overdrive, navigating between setback and scandal, satisfying some but not all of its critics. But on one issue the museum has successfully courted laudatory media coverage: its outreach to African Americans. “We need to include more people of color,” then-curator Seth Pollinger commented to BuzzFeed News in late 2018. In an attempt to garner broad appeal and enhance its brand, the museum has expanded beyond the evangelical Christianity of its white donors, the Oklahoma-based Greens of Hobby Lobby fame, now self-fashioned as the MOTB’s “founding family.” Performances by gospel choirs and lectures by black pastors and academics soon graced the museum stage.

The main endeavor to attract a racially diverse audience was a special “artifact in focus” exhibit entitled “The Slave Bible: Let the Story be Told.” On display from November 2018 through September 2019, the museum heavily promoted the exhibit on its website. According to a press release, MOTB partnered with Fisk University, from whom the artifact was on loan, and the Center for the Study of African American Religious Life at the Museum of African American History and Culture. Steve Green, original visionary and current chair of the MOTB board, praised the exhibit, commenting on its consistency with his family’s affection for the Bible and its strategic value for reaching a more diverse crowd.

Media outlets from The Root to CBN News to NPR to The Times of Israel covered the story of “The Slave Bible” by echoing the MOTB’s own description of the artifact at the exhibit’s center: a 19th-century Bible edited by white colonial Christians to oppress enslaved Africans in the British West Indies. Many praised MOTB for choosing to cast a light on the dark history of racism and slavery in the United States.

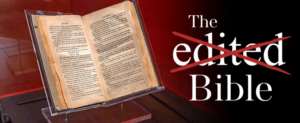

A promotional email from August 2018 summarized MOTB’s interpretation of the artifact. Bearing the subject line “A Bible that was manipulated to emphasize themes of submission and subservience,” the message featured a photograph of the book against a dark background. Superimposed in large white letters was the phrase “The edited Bible.” A bright red “X” went through the word “edited,” resulting in a sleek visual—“The edited Bible”—with an obvious message: this is the Good Book gone bad. The body of the email read:

A promotional email from August 2018 summarized MOTB’s interpretation of the artifact. Bearing the subject line “A Bible that was manipulated to emphasize themes of submission and subservience,” the message featured a photograph of the book against a dark background. Superimposed in large white letters was the phrase “The edited Bible.” A bright red “X” went through the word “edited,” resulting in a sleek visual—“The edited Bible”—with an obvious message: this is the Good Book gone bad. The body of the email read:

There is neither Jew nor Greek, there is neither slave nor free, there is no male and female, for you are all one in Christ Jesus. (Galatians 3:28, ESV)

Imagine a Bible that starts with creation but then jumps right to Joseph being sold into slavery and makes a point of how imprisonment benefited him! An edited Bible, where the Exodus story of God rescuing his people from slavery in Egypt is removed, together with every reference to freedom, such as the above passage from Galatians. A Bible that is manipulated to emphasize themes of submission and subservience. Does this sound like the Bible you know?

In the early 1800s, Rev. Beilby Porteus, bishop of London, instructed a group of missionaries to create such a book.

“Prepare a short form of public prayers . . . together with the select portions of Scripture . . . particularly those which relate to the duties of slaves towards their masters.”

It is a morality tale that most are likely to support in this day and age. But, unfortunately, it’s not a true story.

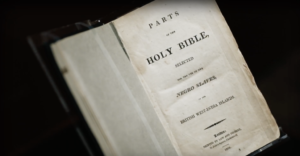

It seems that no one actually gave the “Slave Bible” a closer look. It’s not a Bible. Not really. Published in London in 1807 (and again in 1808) on behalf of the Society for the Conversion of Negro Slaves, the book bears the title Select Parts of the Holy Bible for the Use of the Negro Slaves in the British West-India Islands. Its producers were candid about its contents as partial. One might wonder, then, what rhetorical work is being done by interpreters and curators who have deemed the book a Bible—the “Slave Bible.” If it is not actually a Bible, why call it so?

The answer, the evidence suggests, is that such a move exculpates the Bible from complicity in slavery, placing blame squarely on the human manipulators who tampered with the Bible as they enslaved other humans. The Bible, then, joins enslaved Africans as a victim of white European enslavers and their allies. Ken McKenzie, then-CEO of MOTB, articulated such a perspective in an on-screen interview in April 2019 in response to NBC Nightly News’s Geoff Bennett, who asked the museum official: “When people encounter this exhibit, what lasting impression do you want them to leave with?” McKenzie replied, “Well, we want to pass the message on that ‘may this never happen again.’” While one might expect his “this” to refer to the enslavement of human beings, he instead continued, “The Bible itself is a, is a whole book; it’s not one that you get to carve up and use this piece or that piece.”

McKenzie’s language about this artifact’s production process mirrors the picture we get in the museum exhibit and promotional materials: the book’s producers are represented as starting with a “complete” Bible and calculatedly suppressing its liberative content through excision of freedom-related passages. As one placard in the exhibit read, “Its publishers deliberately removed portions of the biblical text, such as the Exodus story, that could inspire hope for liberation.” The image we end up with is a wounded Bible—one that has been cut and left in pieces. It bears lacerations, unhealed scars, missing members. It limps— afflicted, constrained, hacked to pieces. If the Bible is a (co)victim, it can’t be a (co)perpetrator.

But the museum has exaggerated the supposed scars. In fact, the museum’s claims about the contents of this artifact do not line up with its actual content. If the publishers were, as MOTB suggests, weaponizing the Bible in the cause of slavery, they didn’t do a very good job. Several texts that support slavery as an institution (Exodus 21:2-11; Deuteronomy 15:12-18) and a long discussion of how the enslavement of non-Israelites was acceptable to Israel’s god (Leviticus 25:39-46) were not included. Passages from the Pauline corpus supportive of slavery do not make an appearance either (1 Corinthians 7:21-24; Colossians 3:22-4:1; Philemon).

Most significantly, the museum’s oft-repeated claim that the Exodus is absent is only partially true. God’s redemption of the Israelites from slavery in Egypt is recalled over and over again. Consider this series of verses that were included in the so-called “Slave Bible”:

I am the Lord your God, who brought you out of the land of Egypt, out of the house of slavery (Deut 5:6, NRSV).

Remember that you were a slave in the land of Egypt, and the Lord your God brought you out from there… (Deut 5:15, NRSV).

. . . take care that you do not forget the Lord, who brought you out of the land of Egypt, out of the house of slavery (Deut 6:12, NRSV).

. . . you shall say to your children, “We were Pharaoh’s slaves in Egypt, but the Lord brought us out of Egypt with a mighty hand” (Deut 6:20-21, NRSV).

. . . do not exalt yourself, forgetting the Lord your God, who brought you out of the land of Egypt, out of the house of slavery… (Deut 8:14, NRSV).

Neither is eschatological hope absent from the “Slave Bible.” While the artifact does not include the book of Revelation, it does include both 1 Corinthians 15 and 1 Thessalonians 4-5, two important New Testament passages with expectations for a redemptive future.

MOTB’s interpretive mistakes compound in its framing of the artifact’s historical context. In exhibit signage and promotional messages, the museum has truncated a 19th-century quotation to make it appear compatible with the exhibit’s storytelling. On one exhibit wall appeared an 1808 quotation attributed to Rev. Beilby Porteus, identified as Bishop of London and Founder of the Society for the Conversion and Religious Instruction and Education of the Negro Slaves. It read: “Prepare a short form of public prayers for them . . . together with select portions of Scripture . . . particularly those which relate to the duties of slaves towards their masters” (bold original).

The quotation is excerpted from a letter to “the Governors, Legislatures, and Proprietors of Plantations, in The British West-India Islands.” Rev. Porteus’s aim is to convince these readers to allow enslaved Africans time and resources to receive Christian religious instruction. Porteus envisions a labor-free Sunday so that the enslaved can gather and be formed into Christian slaves. He speculates that local clergy would be willing to prepare “a short form of public prayers for them [the enslaved], consisting of a number of the best Collects of the Liturgy, the Creed, the Lord’s Prayer, and the Ten Commandments, together with select portions of Scripture, taken principally from the Psalms and Proverbs, the Gospels, and the plainest and most practical parts of the Epistles, particularly those which relate to the duties of slaves towards their masters.”

The museum has taken Porteus’s quotation out of its context and edited it to make it say something it does not say. When we read the unabridged statement, we find that he was not issuing a command, and specifically that he was not issuing a command to produce a Bible. Porteus envisioned a collection that expanded beyond biblical texts and included liturgy for public worship. Such an anthology would have been similar to other compilations of biblical and religious texts intended for liturgical or devotional use, examples of which can be found displayed with appreciative tone at the museum.

Notice too that Porteus’s proposed production process is one of building from the ground up. He wants the clergy to curate biblical passages deemed most relevant and situate them among other kinds of religiously useful texts. Since Select Parts of the Holy Bible includes only biblical texts, this artifact does not precisely embody what Porteus was commending. But if we think with the Porteus quotation as a lens to understand how Select Parts of the Holy Bible came to exist, as the museum invites us to do, it turns out that we must shift our thinking from cutting to curating—not a Bible carved to pieces but a blank canvas ready to be filled.

Notice too that Porteus’s proposed production process is one of building from the ground up. He wants the clergy to curate biblical passages deemed most relevant and situate them among other kinds of religiously useful texts. Since Select Parts of the Holy Bible includes only biblical texts, this artifact does not precisely embody what Porteus was commending. But if we think with the Porteus quotation as a lens to understand how Select Parts of the Holy Bible came to exist, as the museum invites us to do, it turns out that we must shift our thinking from cutting to curating—not a Bible carved to pieces but a blank canvas ready to be filled.

The full context of Porteus’s statement gives us a clue as to what his criteria for inclusion of material would have been. Museum curators have excised a significant segment of Porteus’s statement that makes the phrase “particularly those which relate to the duties of slaves towards their masters” appear to refer to all of scripture, when it actually refers to “the plainest and most practical parts of the Epistles”—a phrase which shows that Porteus was motivated principally by a desire to offer enslaved readers texts deemed easily digestible and relevant to their experiences. He was not playing seek and hide with freedom-themed Bible verses.

The book he imagines is not very different from other compilations of biblical passages aimed at making the Bible accessible or relevant for a particular population of people with similar circumstances. MOTB has published examples of such tailored books of Bible content, available for purchase in the museum store. It also holds historical analogues in its collection, such as this abridged Bible from 1786 or the “Souldier’s Pocket Bible.” The latter, said to be originally issued for Oliver Cromwell’s army and then reissued for American soldiers during WWI, bears a longer title that explains the reason for its abridgement down to about 100 verses that all deal with how to behave during war: this pocket-sized book was intended to “supply the want of the whole Bible, which a souldier cannot conveniently carry about him.” Something is better than nothing, the logic goes. And the something is envisioned as particularly helpful for the intended population of readers. The producers’ motivations were more mercenary than monstrous.

Partial Bibles are not uniformly condemned by the museum. The difference between what’s acceptable and what’s not is not based on the act of curation itself. Tailoring is not inherently evil. Abridgement is not necessarily manipulative. Why, then, is such activity represented as the main problem in the “Slave Bible” exhibit? Why present tailoring and abridgement in this case as a stark moral issue? And while we’re posing questions: what led MOTB to distort the facts around this artifact so significantly?

The answer has to do with saving the Bible: slavery is nearly universally condemned in our 21st-century collective American conscience, and MOTB protects “the whole Bible” (and thus the Bible) from blame for such a moral evil by falsely aligning the partial Bible with devious manipulation. By representing the act of cutting up the Bible into Select Parts of the Holy Bible as an evil act, the museum effectively situates the alternative—the whole Bible—on the other side of a moral binary that successfully (if illogically) exculpates the Bible from complicity in slavery.

Indeed, all of the museum’s mistakes are explicable when we identify the ideological commitment underlying the exhibit: the notion that the Bible is inherently good. The claim that the Bible, properly whole, properly applied, is universally beneficial and even benevolent cannot be historically sustained but nevertheless animates the Impact of the Bible floor at MOTB and repeats an apologetic refrain promoted on occasion after occasion after occasion by members of the Green family.

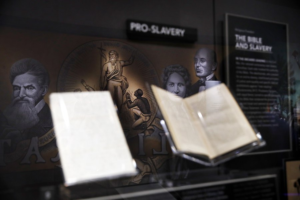

The “Slave Bible” exhibit implies further problematic ideas, including that enslaved Africans depended on literacy to discover and use the Bible (they didn’t), that cutting up a Bible couldn’t be faithful and freeing (it could), and that the Bible’s stance on slavery always determined white Christian colonists’ own stance (it didn’t). Moreover, the museum’s portrayal of the missionaries who produced Select Parts of the Holy Bible as deceitful schemers and the “whole” Bible as self-evidently liberative falsely communicates that the Bible would have to be tampered with in order for it to support slavery. A casual flip through this artifact would provide all the counter-evidence one needs to see that this claim cannot be sustained. So would a casual flip through any Bible. In the struggle over slavery through scripture, antislavery and abolitionist writers had to do far more hermeneutical work than did proslavery readers to make the Bible work in their favor.

The “Slave Bible” exhibit implies further problematic ideas, including that enslaved Africans depended on literacy to discover and use the Bible (they didn’t), that cutting up a Bible couldn’t be faithful and freeing (it could), and that the Bible’s stance on slavery always determined white Christian colonists’ own stance (it didn’t). Moreover, the museum’s portrayal of the missionaries who produced Select Parts of the Holy Bible as deceitful schemers and the “whole” Bible as self-evidently liberative falsely communicates that the Bible would have to be tampered with in order for it to support slavery. A casual flip through this artifact would provide all the counter-evidence one needs to see that this claim cannot be sustained. So would a casual flip through any Bible. In the struggle over slavery through scripture, antislavery and abolitionist writers had to do far more hermeneutical work than did proslavery readers to make the Bible work in their favor.

Plenty of people with “whole” Bibles have read their Bibles and concluded that they supported slavery. Even though the missionaries who produced Select Parts of the Holy Bible were not manipulating a Bible with malintent, they were engaged in other activities that we are likely to find abhorrent today. Lest Reverend Porteus be exculpated, we must note that racism and paternalism fueled his commendation of Christian education for the enslaved. In his letter, Porteus portrays converted slaves as feathers in the caps of their owners, calling them a “pleasing and interesting spectacle, of a new and most numerous race of Christians ‘plucked as a brand out of the fire,’ rescued from the horrors and superstitions of Paganism.” Yet if conversion was intended to rescue enslaved Africans from horrors, it was not horrors in the here-and-now. Porteus reasons that Christian slaves work harder and are more compliant than those who do not convert. He argues that plantation owners should allow their slaves to receive Christian religious education so that their sexual activity can be controlled with the hope of producing more offspring. More enslaved babies, more slaves, more labor, more profit.

An opening placard in the exhibit attempted to acknowledge the relationship between the “Slave Bible” and missionary efforts to convert the enslaved. Interestingly, though, conversion and education efforts were not lumped together with the missionaries’ perceived Bible blunder: “These missionaries aimed to do more with the Slave Bible than convert and educate enslaved Africans. They edited the Slave Bible in a way that would instill obedience and preserve the system of slavery in the colonies.” This framing implies that conversion and education are not activities that deserve interrogation. The curators suggest that these activities are innocent. A line is crossed, it seems, when the missionaries went further: when they messed with the Bible in order to oppress enslaved Africans into peaceful servitude to white plantation owners.

The logic is made explicit in the text overlaying the virtual tour of the exhibit on the museum’s YouTube channel: “A British missionary organization created the Slave Bible. They hoped to convert enslaved Africans but also reinforce the colonial slave system.” The adversative but invites the viewer to weigh these activities in opposition to one another. Converting, good. Reinforcing slavery, bad. As New Testament scholar Allen Dwight Callahan has observed in his analysis of a similar historical train of thought, “Slavery backhandedly facilitated the conversion of Africans, dragging them bound and shackled into the light of the Christian Gospel.”

Converting and educating slaves were not innocuous activities occurring in an ideological vacuum. The exhibit’s sole focus on the use of the Bible in missionary efforts encourages visitors merely to question what was happening with the Bible rather than inviting them to question the larger framework in which the Bible was implicated in the African slave trade. (This move repeats an analogous problem from the MOTB’s precursor traveling exhibit called Passages, which minimized Christian complicity in the Holocaust.) The “Slave Bible” exhibit leaves no room for visitors to question how biblical texts shaped Christians who supported the racialized system of enslavement. Their Christianity, informed by the “whole” Bible, allowed for racism, paternalism, oppression, and acceptance of the enslavement of other human beings. Rather than asking what these missionaries did to the Bible, perhaps we should be asking what the Bible did to them.

In one noteworthy quotation on display in the “Slave Bible” exhibit, Brad Braxton, the director of the Center for the Study of African American Religious Life at the National Museum of African American History and Culture, pushed past the false equivalencies animating MOTB’s overall presentation with this challenge: “In our interpretations of the Bible, is the end result domination or liberation?” The moral compass here is distinct from the rest of the exhibit in an important way: Braxton’s question subjects the use of the Bible to a moral imperative that he does not claim, circularly, to be the right, true, self-evident message in the Bible. It opens up an intriguing possibility so far unimagined in the exhibit: that the Bible isn’t good by itself. It’s what readers do with the Bible that is good or bad.

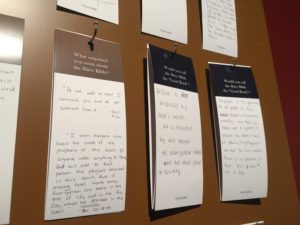

But as soon as such a possibility opened, the museum forcefully shut it down. At the exhibit’s exit, visitors were invited to respond to what they had seen in an interactive crowd-sourced reflection. Visitors were to write answers to prompts and then add them to the previous responses on the wall. “Would you,” one of the questions asked, “call the Slave Bible the ‘Good Book’?” Guests divided over whether the answer was “yes” or “no.” Yes, some said, because it still contained some of God’s Word. No, others replied, because it didn’t contain all of God’s Word. But they all accepted the fundamental premise: that the Bible is supposed to be the Good Book. It is difficult, perhaps even impossible, to resist the premise of this question.

But as soon as such a possibility opened, the museum forcefully shut it down. At the exhibit’s exit, visitors were invited to respond to what they had seen in an interactive crowd-sourced reflection. Visitors were to write answers to prompts and then add them to the previous responses on the wall. “Would you,” one of the questions asked, “call the Slave Bible the ‘Good Book’?” Guests divided over whether the answer was “yes” or “no.” Yes, some said, because it still contained some of God’s Word. No, others replied, because it didn’t contain all of God’s Word. But they all accepted the fundamental premise: that the Bible is supposed to be the Good Book. It is difficult, perhaps even impossible, to resist the premise of this question.

MOTB severely limited the choices for how people today can make meaning out of the existence of this historical artifact. The exhibit’s ideological commitment to the inherent goodness of the Bible distracts us from the suffering of enslaved Africans and also invites us to ignore harrowing present-day stories narrated by those who have endured abuse from (often well-meaning) Bible-believing folk and who have experienced firsthand that the Bible is not good for them.

The special exhibit has now run its course and the artifact is back at Fisk University. But the museum’s framing persists in the widespread media coverage that replicated MOTB’s narrative, which is actually more of a fable. The moral of the story for this museum that celebrates the Bible and commends its central place in American public life is that the Bible is good for us. The moral of this story is that we can’t believe everything the Museum of the Bible tells us.

Jill Hicks-Keeton is Assistant Professor of Religious Studies at the University of Oklahoma. She is author of Arguing with Aseneth: Gentile Access to Israel’s Living God in Jewish Antiquity (Oxford University Press, 2018) and the co-editor of The Museum of the Bible: A Critical Introduction (Lexington/Fortress Academic Press, 2019).