The Sikh State Built on Migration Abroad Now Wrestles with Migration Within

The rising anti-migrant hostilities in India’s state of Punjab

(Image source: Asia Times/Wikimedia Commons)

“No one cares about ‘bhaiya’ [a Hindi slang word for poor migrants] like us,” says Suman (30), adjusting the kettle on the flickering stove at her roadside tea stall. Originally from Hardoi, a town in the northern Indian state of Uttar Pradesh, Suman has been living in Punjab—India’s Sikh state—for almost 14 years with her husband and two children. Now settled in a migrant-dominated village, she has seen how quickly tempers can flare—and how easily her family’s concerns are ignored.

Almost a year ago, a fight broke out between a few men at her tea stall. When she intervened, she too was dragged into the chaos. Suman called the police, but no one came. “Not the police, not even the local leaders—they don’t listen to us,” she says, her voice carrying the weight of resignation that many like her have come to accept.

Suman’s experience is far from isolated. Over the past year, Punjab has witnessed a rising wave of hostility toward migrant workers from other Indian states, with communities not only treating them as outsiders but actively pushing them out.

This is in stark contrast to Punjab’s long-standing legacy of mobility. For decades, the state has proudly worn its reputation as India’s migration capital, sending waves of its own people to countries like Canada, the United Kingdom, and Australia in pursuit of opportunity and prestige. Remittances from this diaspora have helped build not only homes and gurdwaras (Sikh places of worship), but a shared cultural imagination of opportunity and aspiration.

Yet, as working-class migrants from poorer Indian states like Uttar Pradesh and Bihar arrive in Punjab to fill its labor shortages, they find themselves unwelcome. The Sikh state, built on migration abroad, is now grappling with migration within, revealing a deep discomfort with internal mobility that mirrors the very exclusions its own emigrants once faced overseas.

This rising hostility also jars with Sikhism, Punjab’s dominant faith, which upholds values of equality, hospitality (seva), and care for the vulnerable. These ideals, embodied in the principle of sarbat da bhala—the wellbeing of all—stand in contrast to the exclusion migrants often face. Yet in everyday politics and public discourse, such ethical commitments are often overshadowed by growing concerns over land, jobs, and identity.

A Village Resolution Against Migrants

In August 2024, the village council of Mundho Sangtian, a village in Punjab’s Mohali district, passed a controversial resolution ordering migrant workers to vacate the area. The resolution bans local residents from renting homes to migrants and blocks them from obtaining official identity documents within the village.

The crackdown is especially jarring given the demographics: out of the village’s population of 1,500 people, only about 50 are migrants, mostly from the Indian states of Uttar Pradesh, Bihar, and Rajasthan. At least 30 have lived there for over a decade and have voter ID cards registered at their current addresses—proof of their integration into the village.

Local villagers justify the move by citing rising crime and “anti-social activities,” which they claim threaten the safety and well-being of the community. “The decision was unanimous,” says Manjit Singh, a village council member. “There was an incident involving a migrant woman’s misconduct, and there have been thefts where migrant children were involved.”

The narrative of crime linked to migrants is a familiar one, but it is often fueled by long-standing prejudices rather than verified data. In this case, at least 300 residents of Mundho Sangtian signed the resolution, effectively barring migrants from staying in the village. Fearing further backlash, most migrant families moved out in the following months.

The hostility toward migrants isn’t confined to Mundho Sangtian. In Jandpur, a village in Kharar, Punjab, similar anti-migrant sentiment took a more visible form. Banners have been put up across the village, displaying a set of 11 strict rules targeting migrant residents.

One particularly alarming rule prohibits migrants from being outside after 9:00 PM, effectively imposing a curfew on them. Other restrictions include mandatory background checks of migrants by the police, and a ban on smoking cigarettes, chewing tobacco (gutka), and chewing betel leaf (paan)—the latter two framed as efforts to prevent spitting on village roads. Landlords are also required to provide dustbins for tenants, a directive that originally applied only to migrants but has since been extended to all renters.

The initial backlash from migrant workers led to minor revisions. After protests by migrant laborers, the wording of the banners was changed to replace “migrants” with “tenants,” making the curfew and other restrictions ostensibly applicable to everyone. However, the underlying intent remains clear.

“We had a meeting with the police and the administration, and thus we got the boards changed,” says Govinder Singh Cheema, the area councilor. “The same rules will apply to everyone.”

Kharar Deputy Superintendent of Police (DSP) Karan Sandhu maintains that the situation is under control. But for many migrant workers, the message is loud and clear: they are not welcome.

The resolution by the village council was soon challenged in the Punjab and Haryana High Court in late August. Migrant rights advocates and legal experts argued that the move violated constitutional protections of equality and freedom of movement. The High Court issued notices to the state government, seeking a response. As of now, the case remains pending, but the court’s intervention has stalled the immediate enforcement of the resolution. The outcome will likely set a precedent for how far local bodies can go in regulating migrant residency in rural India.

But as villages tighten their grip on who belongs and who doesn’t, the exodus of migrants from Punjab’s rural pockets may just be beginning.

Punjab and its Notorious Migration

Punjab, the Sikh state of India, has long been an agriculture-dominated state. Often referred to as India’s “food bowl,” the Green Revolution of the 1960s brought a transformative shift to its economy and rural landscape, introducing high-yielding varieties of crops, mechanized farming, and increased irrigation. This period of agricultural boom not only ensured national food security but also elevated Punjab to one of the most prosperous states in the country. However, this prosperity came with a growing demand for labor—one that the local workforce alone could not sustain.

Simultaneously, Punjab has also emerged as one of India’s leading regions for international migration.

Historically, Punjab’s high migration stems from colonial-era recruitment of Punjabi men—especially Sikhs—into the British army and as laborers in countries like Canada, the United Kingdom, and East Africa. Post-independence, factors like land fragmentation, limited local opportunities, and well-established diaspora networks further reinforced migration as a viable and aspirational route abroad.

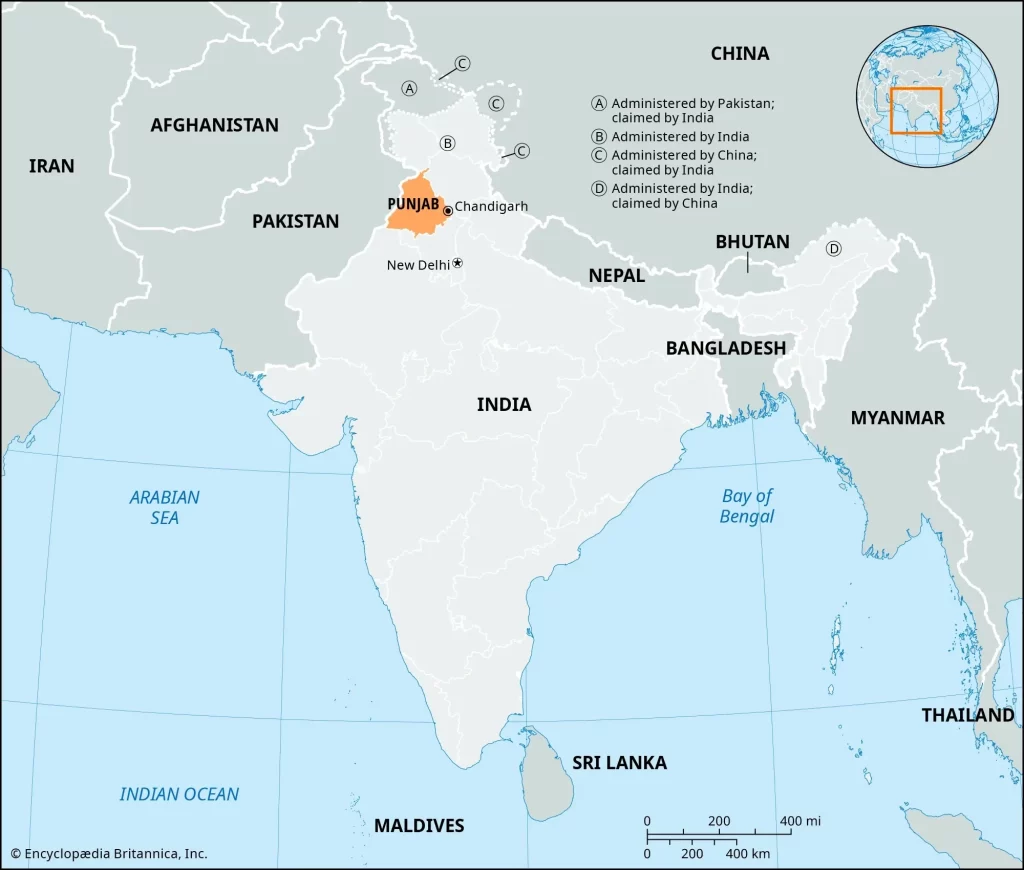

(Image source: Encyclopedia Britannica)

The Punjabi diaspora is well-documented, with nearly one million people emigrating from Punjab and Chandigarh between 2016 and February 2021. A 2023 study reveals that Punjab has the second highest proportion of households involved in international migration, after Kerala. In Punjab, 13.34% of rural households have at least one family member living abroad, primarily concentrated in Britain, Canada, the United States, Western Europe, Southeast Asia, the Middle East, Australia, and New Zealand.

While several Indian states such as Kerala and Uttar Pradesh have also witnessed large-scale international migration, what sets Punjab apart is the sheer concentration of its diaspora in Western nations and the resulting per capita impact. Remittances from abroad have significantly contributed to the state’s economy, while also fostering strong transnational family networks and cultural exchanges. But this large-scale emigration has also created a paradox: as Punjabis move abroad in large numbers, a vacuum has emerged in the local labor market.

This shortage of labor, particularly in agriculture and construction, has over time been filled by migrant workers from other Indian states—primarily Bihar and Uttar Pradesh. Scholars and policymakers alike have noted this shift. According to Manjit Singh, a professor of sociology at Panjab University, the influx of migrant labor into Punjab began with the Green Revolution, when the agricultural boom dramatically increased the demand for labor. “The dependency on migrant laborers has been so critical,” he notes, “that Punjab’s agricultural economy would struggle to function without them.” Over the decades, this dependency has only deepened. As the cropping pattern in Punjab shifted toward monoculture—particularly of wheat and rice—the demand for intensive manual labor grew, especially during sowing and harvesting seasons.

Sikal Yadav’s journey from Bihar to Punjab is emblematic of how migration—both inward and outward—continues to reshape the state’s agrarian landscape. He arrived in Diwala village, Ludhiana, in 2004, initially taking up a series of menial jobs: loading tractors, working on construction sites, and assisting local farmers. Over the years, as he became familiar with the rhythms of agricultural life, Sikal transitioned into farming—but not on land he owned. He now cultivates vegetables, corn, and cumin on a sublet plot of land, a rare opportunity that emerged only when the local landowner’s children moved abroad.

“The sardar’s [a term commonly used in Punjab to refer to a Sikh man] two sons had no interest in farming,” Sikal explains. “They always wanted to settle overseas, and once they did—one to Canada, the other to Australia—he managed the land himself for a while. But with age catching up and no one in the family willing to take over, he eventually sublet the farmland to me.”

For Sikal, it was a turning point. What had begun as seasonal, precarious labor slowly transformed into a stable livelihood.

Sikal Yadav’s story is far from unique. In both villages and urban centers of Punjab, the presence of migrant workers is unmistakable. Whether in industrial belts, sprawling farmlands, or behind the counter of the nearest paan shop, these workers—often accompanied by their families or members of their extended village networks—form an essential part of the state’s labor force. Locally, they’re commonly referred to as “bhaiya”, a term that, while seemingly benign, carries with it subtle undertones of class-based disdain.

According to 2016 data from the Shiromani Akali Dal, Punjab is home to approximately 3.9 million migrants. Over the years, this number has continued to rise. Among the millions are individuals like Sikal Yadav, who left Bihar in search of better opportunities.

The influx of migrant workers from states like Bihar and Uttar Pradesh has also been driven by a combination of factors. Chronic poverty, limited employment opportunities, and underdeveloped rural economies in their home states push many workers to look elsewhere. Punjab, with its relatively higher wages for agricultural labor, presents an attractive alternative. Migrant workers in the state often earn more than they would back home, particularly during peak harvesting seasons.

A 2008 study published in the Agricultural Economics Research Review found that before migrating, 64% of surveyed laborers earned less than ₹20,000 annually ($230 USD) in their home states, and 60% struggled to secure even 200 days of work in a year. Nearly a quarter of them were completely unemployed, but migration dramatically altered their economic trajectories. In Punjab, 63% of those same workers reported annual earnings between ₹20,000 and ₹50,000, while 34% earned more than ₹50,000. The impact ripples far beyond the individuals themselves—an estimated 60% of their income was sent back as remittances, helping to support families and communities in some of India’s poorest regions.

At the same time, many Punjabi farmers reportedly prefer hiring migrant labor due to the growing shortage of local workers and the seasonal tendency among local laborers to demand higher wages. Migrant workers, in contrast, are seen as more consistent, available, and cost-effective during the most labor-intensive times of the agricultural calendar.

A Migrant Takeover?

This interdependence, however, is not without its tensions. The growing reliance on migrant workers in Punjab—both seasonal and permanent—has also triggered a range of socio-economic challenges. Issues of identity, exclusion, and labor rights frequently arise, especially as the state continues to grapple with demographic changes driven by both outbound and inbound migration.

While the Sikh community in Punjab has long upheld the values of community and sarbat da bhala (welfare of all), tensions surrounding the influx of migrant workers have occasionally surfaced in the political arena. A notable instance occurred in February 2022, when then-Chief Minister Charanjit Singh Channi, during an election rally in Rupnagar town, urged Punjabis to prevent outsiders from ruling the state. In April 2024, during his campaign as an Independent candidate for the Bathinda Lok Sabha seat, Lakha Sidhana publicly criticized the influx of migrant workers from Bihar and Uttar Pradesh. He accused them of “stealing jobs” meant for Punjabi youths and altering the state’s demographic composition. Sidhana urged local villagers to prevent these migrants from being enrolled as voters, arguing that their participation in the electoral process could further marginalize native Punjabis in employment opportunities.

But on the ground, labor organizers say the issue is less about identity and more about economics. According to Dharmveer Jaura of the Asangathit Mazdoor Union, the confrontation between locals and migrant workers stems from job insecurity and wage disparity. “When we think of Biharis in Punjab, the dominant image is still that of a poor laborer,” he says. “But that image is fast changing.” Jaura notes that in several areas, migrants from Bihar and eastern Uttar Pradesh are no longer confined to low-paying, menial jobs. “Migrants are everywhere. Some are running their own businesses, setting up small shops, and in certain cases, even earning more than locals. That is where friction begins.”

He attributes this tension to the perception that migrant workers—particularly in sectors like agriculture, brick kilns, and construction—are often willing to work for lower wages than locals. “When labor is readily available at cheaper rates, employers naturally prefer it. This leaves many local workers struggling to find consistent employment,” Jaura explains. “The result is a sense of displacement among the local population, which sometimes expresses itself in resentment or even aggression toward the migrants.” He warns that unless addressed through better labor rights and policy safeguards, these underlying tensions could deepen in the years to come.

In recent years, demographic shifts brought about by large-scale in-migration have become increasingly visible in Punjab’s social and political fabric. Migrants have not only established deep roots in the state but have also begun contesting local elections—marking a growing assertion of their political presence. However, this participation has also sparked tensions in some quarters, where the growing influence of migrant communities is viewed with apprehension, occasionally leading to socio-political friction.

Who Belongs, and Who Decides?

India’s Constitution guarantees every citizen the right to move freely and reside in any part of the country under Article 19(1)(d) and 19(1)(e). These provisions protect the freedom to migrate, seek work, and live without fear of discrimination. Hence attempts to restrict these rights—based on region, language, or identity—are unlawful.

In that light, the rising tensions against migrant workers in Punjab raise troubling questions. The rhetoric of “outsiders stealing jobs” or altering demographics echoes a sentiment that is legally unfounded and socially corrosive. Efforts to prevent migrants from voting, deny them tenancy, or restrict their access to employment are not just discriminatory—they are illegal.

These anxieties are also not new. As far back as 2004, the Punjab government’s Human Development Report devoted an entire chapter to the issue, titled “Migrant Labour: Problems of the Invisible.” The report acknowledged how migrants are often seen as the problem, rather than as people facing problems. “Since the migrant labourer is considered an ‘outsider’ in a cultural, linguistic and class sense,” it stated, “the focus is always on ‘the migrant as a problem’, rather than the ‘problems of the migrant’.” The irony wasn’t lost on the report’s authors, who noted that in a state famed for its global diaspora, domestic migrants deserve far better treatment.

The report laid bare a system in which migrant workers were routinely denied rights. Many were not registered as voters, had no role in local governance, and remained invisible in the planning process. “Harassment and extortion by police, other departments such as railways, post office and antisocial elements at the workplace, in workers’ residential colonies and during the journey,” were listed among the chronic challenges migrants faced. Though trade unions attempted to advocate for them, their efforts were limited by weak organizing and the complete dependency of workers on their employers.

Two decades later, little has changed. Migrant workers still remain easy scapegoats in times of economic distress, underpaid and undervalued even as they power the economy’s most crucial sectors. They are talked about in terms of burden and threat, but rarely in terms of rights, dignity, or justice.

As Dharmveer Jaura puts it, the hostility migrants face today in Punjab is not just unjust—it is deeply ironic. “This is a state where most of its own youth is desperately pushing themselves to go abroad,” he says. “Yet we deny dignity to those who come here chasing the same dream.”

Anuj Behal is an independent journalist and researcher focusing on issues of urban justice, gender, and migration in India.