The Rise of Oilfield Evangelism

The commingling of conservative Christianity, corporations, and the fossil fuel industry's fragile workforce

(Image source: Cunningham & Mears)

When Brendan Marble leaves home each morning for work in the oil fields of West Virginia, he carries with him a stack of Bibles and a willingness to talk to anyone he meets about Jesus. As he drives between thousands of active oil and gas wells—their concrete drilling platforms cutting into the region’s rolling hills and thick forests—he meets technicians, engineers, and operators with varying degrees of spiritual conviction, from Christians who want to grow their faith to those who don’t consider themselves religious at all. Some are even openly hostile towards religion.

As the founder of Oilfield Evangelist Ministry, a nonprofit that provides Bible study resources and mentorship for oil and gas workers, Marble sees it as his calling to share his faith with others in his line of work. During free time at the sites, while others are talking about sports, he tries to “direct the conversation to the spiritual,” sharing books and videos when someone seems interested in learning more.

He knows that each interaction is fleeting. With the transient nature of the work and the high turnover rates, he will never meet most of the people he speaks with again. But Marble, who works as a traveling safety consultant, estimates that he’s had thousands of conversations with others in the industry, where the high-pressure environment and high risk of accidents and injuries can make even the most hardened ponder spiritual questions.

“We’ve always got to be thinking about what’s going to happen the moment we take our last breath,” Marble said. “I want to do everything I can to share the gospel with as many people as I can, so they have an opportunity to hear the truth and respond to that truth.”

Marble’s ministry is just one among a network of evangelical organizations that target Christians in the oil and gas industry, a notoriously volatile field that experienced even more instability during the COVID-19 pandemic because of fluctuations in oil prices. Though U.S. crude oil drilling is at a record high, the number of people employed in its extraction is shrinking each year, as new technology reduces the need for workers to operate machinery, and falling oil prices cause companies to cut back their production. And with the ongoing transition to renewable energy—which is expected to continue despite President Trump’s “drill, baby, drill” agenda—putting the long-term future of the industry in question, many workers fear for their job security.

These anxieties, along with concerns about workplace safety and low pay, make oilfields ripe for conversations about faith and spirituality, as evangelists like Marble have found. At the same time, the work of oilfield ministries builds on a long-standing relationship between religion and resource extraction in the United States, particularly in oil-rich southern and western states like Texas, Oklahoma, and North Dakota. Religious beliefs have helped encourage oil drilling from its earliest days. These beliefs are still widely held; Scott Pruitt, a former oil industry executive who served as director of the Environmental Protection Agency during Trump’s first term, has said that the Bible promotes drilling for coal, oil, and gas as part of humankind’s dominion over the Earth.

“The biblical world view is that we have a responsibility to manage and cultivate, harvest the natural resources that we’ve been blessed with to truly bless our fellow mankind,” Pruitt told the Christian Broadcasting Network in 2018.

In turn, U.S. evangelical Protestants have some of the lowest rates of belief in human-caused climate change among religious groups, in part due to fossil fuel industry support for religious organizations and think tanks that promote climate change denial. Oil and gas companies like Shell donate widely to churches and religious schools in oil-rich states like Texas, Louisiana, and Pennsylvania, according to reporting from The Guardian and DeSmog. Oil and gas workers are around 80 percent white and male, and both demographics tend to be more dismissive of climate change concerns. And although there are no clear-cut numbers on the religiosity or religious affiliation of workers in this industry compared to others, they tend to be receptive to groups like the Oilfield Christian Fellowship, the largest of the oilfield ministries in the U.S.

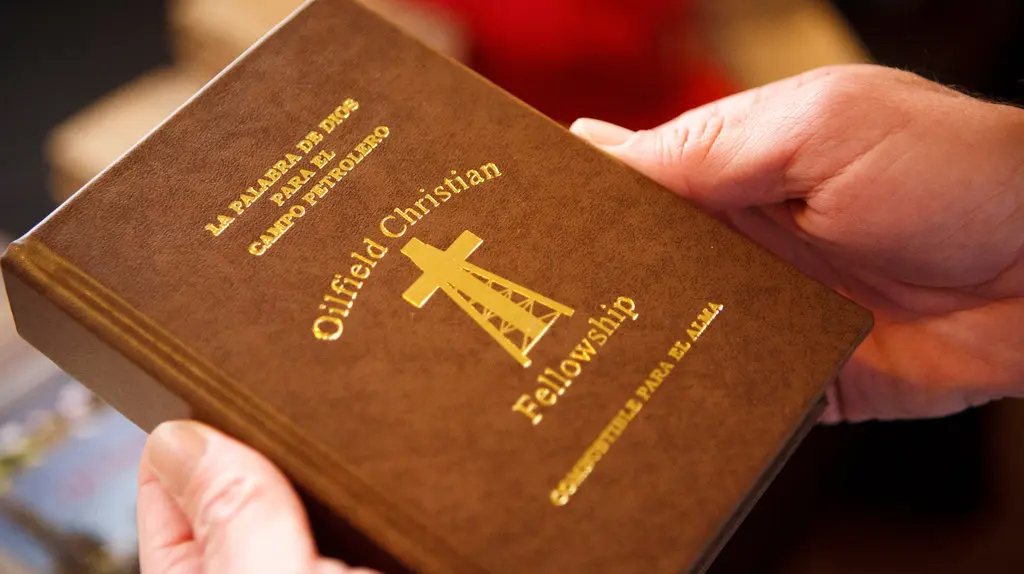

The group was founded in 1991 by a drilling engineer and a chemical salesman who wanted to create a space for Christians in the oil industry to meet. They started hosting monthly prayer breakfasts at a church in Houston and distributing Bibles to oil workers around the world. Although oil and gas companies don’t directly sponsor these events, their executives feature prominently as guest speakers. Last May, the Oilfield Christian Fellowship hosted its 25th annual prayer breakfast during the Offshore Technology Conference, a meeting for oil industry professionals in Houston. The keynote speaker was Alan Smith, the co-founder, president, and CEO of Rockcliff Energy; previous prayer breakfasts have featured executives from companies like Occidental Petroleum, one of the largest oil and gas producers in the United States.

(Image source: Michael Stravato for The New York Times)

This kind of close relationship between religion and oil goes back to the industry’s origins in the late nineteenth century, says Darren Dochuk, a history professor at the University of Notre Dame and author of Anointed with Oil: How Christianity and Crude Made Modern America. Figures like John D. Rockefeller and J. Howard Pew founded major oil companies and used the proceeds to promote Christian ideals, both in the U.S. and abroad. Rockefeller, a northern Baptist, followed what Dochuk termed the “civil religion of crude,” believing the wealth generated by his Standard Oil enterprise was gifted by God and should be applied “for the good of [his] fellow man,” such as for religious education.

In contrast, independent oilmen, who set out to make their fortunes in California, Oklahoma, and Texas, held a “fiercely individual” view of Christianity that prioritized a personal relationship with Christ, Dochuk told The Revealer, which mirrored their desire to extract oil on their own terms and without government intervention. Religious leaders began to fear that without their involvement, the oil patch would become a “violent, secular place,” and set out to create religious institutions in and around oilfields to anchor workers with faith, Dochuk added.

Over the years, oil wealth helped fund the construction of churches around the Southwest, while coal extraction supported the growth of similar institutions in Appalachia. Religious support has in turn helped keep the industry influential, even as calls for a transition to renewable energy to combat climate change have grown more urgent. Communities that depend on the extraction of oil to fund their schools, infrastructure, and religious organizations have leaned into theological support for the industry, even as other prominent Christians have urged the United States to move away from fossil fuels.

“This infrastructure has always rested on this fiercely evangelical worldview that accepts risk, that accepts speculative capitalism that brings with it boom and bust cycles,” Dochuk said. “It’s not fatalistic, but there’s just an acceptance of that as part of the bargain that we make as a society.”

The Oilfield Christian Fellowship doesn’t explicitly take a stance on the transition from fossil fuels. But it does seek to recognize the work that goes into producing energy and support workers through difficult times, said Mike Chaffin, a drilling engineer and the organization’s Bible ministry chairman. He said demand for their Bibles grew during the pandemic even as in-person activities faltered.

“Struggles and problems, faced properly, draw you closer to God,” Chaffin said. “And people knew that they needed something.”

At one point, the fellowship had over 20 chapters in cities around the country as well as Canada and Venezuela, Chaffin said, although the pandemic caused many to close or scale down their activities. One chapter that remained active is in Oklahoma City, where the organization has played a valuable role among the oil and gas workforce since its founding in 2004, said chapter president Jeff Hubbard.

Members keep a prayer request thread going over email, where workers and their families express their struggles to find a job or to care for a sick loved one. They also host events—like an annual tailgate party for oilfield workers—and raise funds for local charities, such as an Oklahoma City homeless shelter. A monthly luncheon regularly draws around 100 attendees who hear from speakers that describe the challenges of working in an industry that goes through constant boom and bust cycles.

Though many people across all fields still avoid talking about religion at work, some research has shown that religious beliefs can influence performance in the workplace. One study from 2023 found a connection between attendance at religious services and higher wages; another, which tracked people working in the banking, education, and tourism sectors in Turkey, found that more religious employees “have a high level of satisfaction with their work, are more committed to their institutions, and experience less burnout by coping with stress factors more easily.” Some companies have embraced religion, hiring chaplains to boost workplace productivity by providing spiritual services.

These practices extend to the fossil fuel industry; the United Kingdom has an official oil and gas chaplaincy, which offers spiritual care to workers and their dependents. Since 2004, many oil and gas companies in the U.S. and around the world have also allowed OCF to distribute a specialized Bible to their workers. Called “God’s Word for the Oil Patch,” the book includes 16 testimonies from oilfield workers around the world, who explain how their faith helped them through everything from marital struggles to battles with alcoholism. Chaffin estimates that the group has distributed about 375,000 Bibles—both the Oil Patch and standard versions—in 69 countries.

That work has made a difference, Chaffin says—though one that reflects a specific concern with what he called maintaining a “family-friendly” atmosphere. He used to see cursing and pornography abound in the oilfield, issues that draw particular concern and condemnation from evangelical Christians in the U.S. By encouraging a reduction in these practices, Chaffin said the Oilfield Christian Fellowship has helped promote what he believes to be a greater respect for Christian values.

Larger trends in the industry have posed both challenges and opportunities to OCF’s mission since its founding; in the past few decades, for example, safety improvements have lowered accident rates significantly, making spiritual support less necessary. At the same time, oilfield workers have had to adapt to whiplash from frequent job cuts as the advent of hydraulic fracturing downsized the oil and gas workforce, leaving many seeking fellowship with others. Only 110,700 people across the U.S. were employed in the oil and gas industry in 2021, less than half of the workforce’s peak thirty years prior.

For some, though, faith is more of a personal journey that’s largely unconnected to the nature of the work that they do, with the oilfield just a workplace like any other. Brendan Marble’s own path to founding the Oilfield Evangelist Ministry started with an inner transformation. A former professional firefighter, he battled addiction for over a decade, and in 2013 he was arrested on drug charges. He had to forfeit his EMT license and faced years in prison. “I got down on my knees,” Marble said. “I was crying like you’ve never seen a grown man cry in your life. And I just cried out to God, and he changed my life.”

Though he had gone to church a handful of times growing up, he started reading the Bible in earnest and resonated with its message of repentance and divine forgiveness. Two months later, Marble started working in the oil and gas industry as a safety consultant, which required him to move between different drilling sites all around West Virginia, conducting inspections and advising companies on how to run their operations. There, he felt compelled to share what he had learned with others working in his industry.

“He called me into the oil field, and I just started preaching,” Marble said. “I just started sharing the gospel, and as I started to mature in my faith, then God was maturing me, working on me, changing me.”

Though his desire to share his faith didn’t start by targeting the oil industry in particular, Marble noticed a particular need for such services in what he called a “spiritually dark industry.” Job insecurity and the dangerous nature of the work lead to ambivalent or even hostile attitudes toward religion, Marble said. He’s had people get angry with him and has feared for his safety at times, though he says he never forces a conversation upon someone who obviously doesn’t want to engage. Oil and gas companies are also willing to hire people with criminal backgrounds—himself included—which Marble said meant that many of the workers he talked to were grappling with inner demons.

“As I got into the industry, and I started talking to people about God, I realized that there are so many people that don’t know God, that hate God,” Marble said. “Of course, I was there at one point, too. But the wonderful thing is that with my past, I’m able to connect with a lot of people in the industry, because a lot of them that I’ve talked to have a very similar path.”

Though he doesn’t see most of the people he evangelizes to again, some have invited him to speak at their churches. Others have told him that his message helped them deal with difficult times, from personal tragedies to job losses and economic insecurity that characterize the work.

“I have had people make a profession of faith in Christ, as I speak with them,” Marble said. “There’s a lot of hurting people out there that need hope.”

That hope may be harder to find, though, as those very oil and gas workers stare down the barrel of a changing energy economy, one that is moving away from fossil fuels without offering alternative employment for the people who extract them. Some religious leaders have responded by calling for a “fair, just transition” to renewable energy—arguing that climate action will ultimately benefit humanity more than pure faith.

“Oil, coal and gas are indeed gifts from God,” Julius Mbatia of the ACT Alliance, a faith-based coalition urging a transition away from fossil fuels, said at the global climate change conference in Azerbaijan last year. “However, God has trusted humanity to care for the creation, not to exploit it.”

Diana Kruzman is a freelance journalist based in New York who writes about religion, climate change, and human rights in the U.S. and internationally. Her work has appeared in publications including the New York Times, Religion News Service, the Christian Science Monitor, and Grist.