Problems with How Journalists Write about Hindu Death Rituals

Legacies of colonial stereotypes about people in India persist in today’s journalism

(Image source: Sanjay Kanojia/AFP)

American pop culture rarely showcases Hindu death and funeral rituals. One notable exception is the 2006 film The Namesake, based on Jhumpa Lahiri’s Pulitzer Prize-winning novel of the same name. When the main character, Gogol, learns of his father’s death, he immediately shaves his head, as is customary for upper-caste Hindu males. He then visits his family home in New York where relatives and friends have gathered to pray and perform funerary rites. Gogol’s white girlfriend, Maxine, joins him and stumbles in her efforts to console Gogol, first by wearing an all-black outfit when everyone else is dressed in white, a color for mourning in Hindu traditions, and second by inviting herself to scatter his father’s ashes in India, a rite usually performed by the immediate family. Through Maxine, viewers witness a stereotypical white American who knows almost nothing about Hindu customs related to death and mourning. Sadly, American journalists writing about pandemic-related deaths in India have demonstrated similarly inadequate knowledge about Hindu death rituals.

In April 2021, at the height of the pandemic in India, news articles such as “Complacency and Missteps Deepen a Virus Disaster in India,” and “How Did the Covid-19 Outbreak in India get so bad?” published in The New York Times and The Washington Post cited large public gatherings, population density, government missteps, and developing-world healthcare infrastructure as reasons for India’s Covid-19 problems. Writing for the New York Times, foreign correspondent Jeffrey Gettleman worried for the safety of himself, his family, and his neighbors, as hundreds of thousands contracted Covid-19 and overwhelmed India’s healthcare system. He writes, “As a foreign correspondent for nearly 20 years, I’ve covered combat zones, been kidnapped in Iraq, and been thrown in jail in more than a few places. This is unsettling in a different way. There’s no way of knowing if my two kids, wife, or I will be among those who get a mild case and bounce back to good health, or if we will get really sick. And if we do get really sick, where will we go? ICUs are full. Gates to so many hospitals are closed.” His stories offer readers in the United States a glimpse of the pain and anguish that he experienced in India at the height of Covid-19, fears shared by many Indians throughout the country. Reporters Shefali Anand and Suryatapa Bhattacharya, writing for The Wall Street Journal, explain how young adults, such as Anisha Saigal, 29, “stood in line for 3 ½ hours at Holy Family Hospital in New Delhi to get a consultation” before being admitted to the pediatric ward since beds were not available. Others, like Priyanka Kumari, 25, who live in small towns where healthcare facilities are far more limited often died before reaching hospitals with ventilators and medicine.

Alongside these accounts, some news media outlets furthered, albeit tacitly, colonial stereotypes of the region, mostly through a poor understanding of India’s religious traditions. Too often, journalists failed to provide their primarily white, Christian, American audiences with information to understand why Hindus engage in particular death rituals and why others within India have different customs.

Over the past several months, I reviewed 103 articles in American newspapers about Covid-19 in India. Only a few explained the significance of religious rites, and they did so briefly. Most, including the examples below, focused instead on descriptions of mass death and mass cremations.

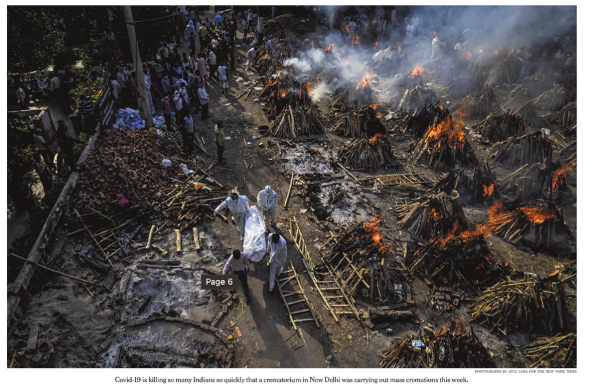

Writing for the New York Times, Jeffrey Gettleman describes cremation grounds vividly: “Crematories are so full of bodies it’s as if a war just happened. Fires burn around the clock. Many places are holding mass cremations, dozens at a time, and at night, in certain areas of New Delhi, the sky glows.” He compares cremation grounds to war zones, often characterized by uncertainty, fear, and disorder, while commenting on the jarring sight of mass cremations occurring throughout the night. The images accompanying these articles depict bodies being prepared for, or undergoing, cremation rites.

(Image source: Atul Loke for the New York Times)

A predominantly white Christian audience that recognizes burial as the most appropriate means of handling the deceased may perceive these open-air mass cremations as undignified if they are unaware why Hindus cremate. Without such an explanation of the history, readers are likely to perceive the practice as foreign and mysterious, especially since open-air cremations are illegal in most places in the United States.

Of the few articles that did explain cremation rites in India, most provided only a cursory overview of the Hindu custom. One New York Times article declares, “Cremations are an important part of Hindu burial rituals, seen as a way to free the soul from the body. Those working at the burning ground said that they were utterly exhausted and could never remember so many people dying in such a short span of time.” The article features visuals of cremations and describes Hindu funerary rites as burials. This claim conflates burial and cremation, elides the region’s religious diversity and reasons for cremation, and echoes colonial sentiments and misunderstandings.

White colonists in India have long depicted Hindu cremation as a barbaric practice. Alexander Duff (1806-1878), the first missionary in India from the Church of Scotland, described Hindu cremation as a disgusting spectacle. In one of his most popular books, India and Its Missions: Including Sketches of the Gigantic System of Hinduism in Theory and Practice (1839), he writes, “In the sacred books [for Hindus] it is required that the body be burnt to ashes on the funeral pile [pyre] – the process being accompanied by various religious ceremonies. The consecrated places for burning the dead are usually at the ghats, or flights of steps at the landing places on the margin of a river. These ghats at all times present spectacles the most disgusting to every feeling mind.” For Duff and his contemporaries, public cremation was an uncivilized religious ritual that did not offer the same dignity as that of the Christian burial.

Duff was not alone in portraying Hindu cremation as primitive. In Burning the Dead: Hindu Nationhood and the Global Construction of Indian Tradition, scholar David Arnold highlights how European colonial officials abhorred cremations, seeing them as repugnant rituals. They denounced cremation and other Hindu traditions to justify British rule for the supposedly uncivilized masses and to present conversion to Christianity as Hindus’ only hope for redemption.

Most Hindus are cremated when they die. Exceptions include babies under the age of two, renunciants (sannyāsīs), and some members of lower social groups such as Dalits, who are buried. Cremation occurs soon after death, often within 24 to 48 hours, and severs any remaining ties or lingering sense of attachment that the self (ātman) may have to the body. The body is prepared for cremation rites by the deceased’s relatives, who ceremonially bathe and clothe the body, anoint the forehead with vermilion marks, and offer flowers, often while reciting devotional verses and songs. Relatives pay their respects to the deceased by garlanding, bowing down to, and circumambulating the body, which are ways of showing reverence in Hindu traditions. The deceased’s eldest son or a close relative ignites the funeral pyre at the cremation grounds. The ashes of the body are collected and ritually dispersed in a body of water. In the United States, Hindus have had to modify these customs because of laws that prohibit public cremations. Instead, Hindus in America conduct their funerary rites in a closed chamber at a local funeral home before the body is taken to a crematorium.

(Image source: Getty Images)

These rituals stem from Hindu beliefs that the immortal and imperishable self (ātman) takes on a body and undergoes a process of reincarnation (punarjanma) until attaining liberation (moksa). The cremation rituals and dispersal of ashes symbolize the body’s return to the natural elements and represent the cyclicality of life.

Many other religious groups in India, including Jains, Buddhists, and Sikhs also cremate the deceased. By labeling all cremation rites as “Hindu,” reporters erase the country’s religious diversity and fail to respect the dead. This erasure echoes eighteenth-century British colonialists, who often used the term “Hindoo” to refer to everyone on the Indian subcontinent who identified as neither Muslim nor Christian.

***

While readers in the United States would find reports of cardboard coffins in Ecuador or mass graves at Hart Island, NY, shocking, they still have the cultural and religious literacy to understand burials. When the same readers were presented with raw footage of open-air cremations in India where bodies were burned around the clock in 2021, they may have concluded, as the colonialists did in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, that Hindus treat the deceased in an inhumane way. The repeated references to and images of cremation in news media exoticize funeral practices and cement differences between the “East” and the “West.” These differences tacitly perpetuate colonial legacies that characterize the “East” as mysterious and backward and the “West” as its opposite – civilized and progressive. Part of mitigating this distance – cultivating understanding and mutual respect for people of different cultures, traditions, backgrounds, and races – requires greater religious literacy.

A Pew Research Study on “What Americans Know About Religion” conducted in 2019 reveals that most residents of the United States have background knowledge on Christianity and the Bible, and some understanding of the meaning of key terms in Islam, such as Ramadan and Mecca. Far fewer Americans, however, could answer basic questions on Jewish, Buddhist, and Hindu traditions. The absence of general literacy on religious minorities in the United States gives journalists the added responsibility of coupling reporting on the what with the why, that is, describing current events as they unfold while also providing readers with the tools to understand those events.

The cultivation and communication of religious literacy – that is, the histories, beliefs, and practices of religious traditions – ought to be paired with an examination of colonial legacies and how they shape contemporary attitudes towards race and religion in the United States. As scholars like Tomoko Masuzawa and Kathryn Gin Lum have shown, classifications of religion, including the labeling of some as “primitive” and others as “ethical,” emerged during the age of European colonialism and continued through the expansion of the United States’ empire. Such taxonomies were political acts that hierarchized religions purportedly rooted in rationality like Protestant Christianity and deemed others that included the worship of objects as primitive. By understanding this history and its legacies in the United States, journalists and readers will become aware of the unchecked and often subtle ways that colonial thought patterns pervade one’s conception of the self and other.

Bhakti Mamtora is Assistant Professor of Religious Studies at the College of Wooster and a Sacred Writes/Revealer writing fellow. Her research examines orality, textuality, and canonization in South Asian and diasporic Hindu traditions.

***

This article was made possible in part with support from Sacred Writes, a Henry Luce Foundation-funded project hosted by Northeastern University that promotes public scholarship on religion.