The Problem with Spotlights: Rethinking Our Response to Clergy Sexual Abuse

Americans repeatedly ask new waves of Catholic survivors to come forward, only to abandon them.

When it comes to Catholic sexual abuse, Americans are stuck in a pattern of cultural amnesia. When the media spotlight shines on abuses in a new diocese or region, we express collective outrage and surprise. When the spotlight dims, we forget about the religious dimensions of child sexual abuse. In turn, Americans repeatedly ask new waves of Catholic survivors to come forward, only to abandon them as soon as our gaze shifts to another seemingly distant tragedy.

When it comes to Catholic sexual abuse, Americans are stuck in a pattern of cultural amnesia. When the media spotlight shines on abuses in a new diocese or region, we express collective outrage and surprise. When the spotlight dims, we forget about the religious dimensions of child sexual abuse. In turn, Americans repeatedly ask new waves of Catholic survivors to come forward, only to abandon them as soon as our gaze shifts to another seemingly distant tragedy.

We repeat this cycle every few years, most recently in the wake of the 2018 Pennsylvania grand jury report. In the opening sentences of the report, the grand jurors lamented the consequences of their own amnesia:

We, the members of this grand jury, need you to hear this. We know some of you have heard some of it before. There have been other reports about child sex abuse within the Catholic Church. But never on this scale. For many of us, those earlier stories happened someplace else, someplace away. Now we know the truth: it happened everywhere.

As the jurors recognized, we tend to imagine the sexual abuse of children as other people’s pain, as something that only happens in other parishes, other families, other communities. But child rape is exceedingly common. Pretending otherwise diminishes the visibility of survivors, while also rendering the specifically religious elements of Catholic abuse even more opaque.

Our willful ignorance about child sexual abuse also raises two problems for Catholic survivors in particular. The first problem is that, historically, clergy sex abuse is not a new phenomenon; it has plagued the Roman Catholic Church for centuries. What is relatively new is the widespread knowledge that the Church aggressively and systematically covered up rapes perpetrated by its own priests. I say “relatively new” because American Catholic survivors have been trying to bring attention to this problem for more than 35 years.

Survivor activist Barbara Blaine

The most intense periods of survivor activism have followed new revelations of abuse, especially in the wake of Jason Berry’s reporting on clergy abuse in Louisiana in 1985; early survivor-leader Jeanne Miller’s advocacy tour in 1988; survivor Frank Fitzpatrick’s emotional prime-time television appearances in 1992; the award-winning reporting of the Boston Globe’s “Spotlight” team in 2002; the separate criminal convictions, in 2012, of Missouri Bishop Robert Finn and Philadelphia’s Monsignor William Lynn; and the recent 2018 Pennsylvania grand jury report.

The second problem is less obvious but more important. By acting scandalized, again and again, at each new wave of clergy sex abuse revelations, we collectively re-harm survivors.

A Voyeurism That Re-Victimizes

In the interviews I have conducted with Catholic victims since 2011, I have seen firsthand how devastating this cycle can be, including in my most recent work with survivors from the Pittsburgh, Harrisburg, and Erie dioceses in Pennsylvania.

Last winter, some of these Pennsylvania survivors were flown to New York and Los Angeles to appear on morning- and afternoon-television talk shows. Media networks wooed them with promises of documentaries and exclusive interviews. Prominent Catholic groups also vowed their support – even sending one of these victims to Rome for Pope Francis’s February summit on clergy sexual abuse. And high-profile attorneys swooped in to recruit these survivors as new clients, reassuring them that their proven track record of suing other dioceses would pave a swift path to justice.

In short, winter 2019 was a season of hope for these survivors, replete with anticipation that not only the Catholic Church but the entire country might finally come to terms with child sexual assault. In this #MeToo era, it seemed we might at last remember that there are actually victims all around us — in all of our families, parishes, and neighborhoods — who need our support.

Survivors after the PA Grand Jury Report

But winter 2020 has been dire for the Pennsylvania survivors I’ve met. Eighteen months after the grand jury report, the journalists have moved on. Newspaper editors stopped taking survivors’ calls. Media producers haven’t followed through on the contracts they had promised. Even survivors’ new attorneys are less responsive, having shifted their focus away from Pennsylvania and towards New York and New Jersey, where recent judicial and legislative shifts meant to help Catholic survivors in those states have also, inadvertently, made their markets more profitable for victims’ lawyers.

Many Pennsylvania survivors will receive some financial compensation, but that is not the case for survivors who long ago reported their abuse to the state. Although today’s media coverage is saturated with reports of multi-million dollar lawsuits, survivors who settled out-of-court with Church attorneys in the 1980s and 1990s routinely received as little as $5,000 to $10,000. When these more seasoned survivors travel to support others who are coming forward for the first time, it is usually at their own expense.

In addition to these social and financial costs, the shift out of the spotlight has also taken an intense emotional toll on the Pennsylvania survivors with whom I’ve worked. They no longer smile and laugh, and several have been clinically diagnosed – for the first time in their lives – with anxiety and depression. Last year, they felt seen and heard. This year, they feel abandoned and silenced. When we turn our interest to a new scandal, we essentially discard the prior survivors who came forward, leaving them isolated and newly-vulnerable.

After the spotlight moves on, survivors face an unstable future. Their most painful and intimate secret is now public. Their family and friends cannot un-know what they have now learned. Frequently, lifelong friendships disintegrate after a survivor publicly reveals that a priest whom their neighbors loved and adored was actually, also, a pedophile.

Multiple survivors have told me that the last time they felt this forsaken and betrayed was in the immediate aftermath of their childhood sexual abuse. This is why survivors, when speaking to each other and their loved ones, often refer to the spotlight’s shift as a form of “re-victimization.”

This term, re-victimization, gives shape to the pain that survivors feel when we perpetually abandon them. The other context in which survivors talk about being re-victimized is when, after reporting their abuse to their local parish or diocese, the bishop failed to remove the abusive priest from contact with other children.

We should note the similarities between the patterns of our cultural amnesia, on the one hand, and the Catholic Church’s empty promises of reform, on the other. In both contexts, the survivors who come forward to share their intimate suffering are ultimately ignored.

The Church silences victims and denies the truth of their pain. But our cultural voyeurism is also harmful. Instead of permanently empowering survivors, our cycles of spotlight create temporary exhibitions of their pain. We leverage survivors’ suffering to fuel our self-righteous rage, and then we move on. These are stories and experiences that most of us don’t have to live, and we can forget about their horrors just as quickly as we can re-visit them.

In short, we have all reduced survivors into entertainment by selectively consuming their pain.

Rethinking Our Affection for Spotlight

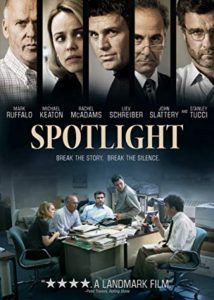

Americans were scandalized by the Pennsylvania report because we forgot, apparently, that there are real victims of clergy sexual abuse. To the extent that we have “remembered” prior waves of Catholic abuse at all, it is through the tropes of heroes and villains. This moral binary is what drives the plot of the 2015 blockbuster film Spotlight, which won the Academy Award for Best Picture.

Spotlight enshrines the heroism of the Boston Globe’s “Spotlight” special investigation team, which in 2002 published more than 600 news articles exposing how the Archdiocese of Boston, under the administration of Cardinal Bernard Law, systematically covered up thousands of abuse cases that were reported to the church.

From a historian’s viewpoint, Spotlight gets many things right. During the first half-hour of the movie, there are shout-outs to Richard Sipe, a Catholic psychiatrist-turned-whistleblower, and to one of the first survivor organizations, the Chicago-based Survivors Network of those Abused by Priests (SNAP). More importantly, the movie acknowledges the relentless courage of Phil Saviano, a survivor who had for years been sending the newspaper evidence of his abuse and its cover-up.

But as Spotlight unfolds, survivors quickly fade into the background.

Whether we assess the film’s priorities by the celebrity of its casting or by each character’s time on-screen, the result is clear: the heroes in Spotlight are the journalists and, to a lesser extent, the lawyers. The movie villainizes Church officials, Catholic donors, and Catholic parochial school leaders, yet their characters also receive significant screen time. Least visible of all are the survivors themselves.

By celebrating journalists, Spotlight leverages survivors’ suffering in order to create a much happier narrative – a heartwarming story, which, at its base, draws upon the myth that America is a land of virtue and hard work. From this perspective, the Church’s wealth and corruption were outdone by the dedication, honesty, and determination of middle-class journalists.

By celebrating journalists, Spotlight leverages survivors’ suffering in order to create a much happier narrative – a heartwarming story, which, at its base, draws upon the myth that America is a land of virtue and hard work. From this perspective, the Church’s wealth and corruption were outdone by the dedication, honesty, and determination of middle-class journalists.

Spotlight is emblematic of the broader challenge of how to make sense of sexual assault survivors, whose unifying trait is a profound tragedy that defies the predominant media tropes of triumph and failure. Survivors’ feat is that they are still here; unlike many clergy victims, they have persevered through the temptations of self-medication and suicide. Survivors don’t see themselves as heroic. Many Catholic victims don’t even see their abusers as evil, understanding them instead as fellow humans who were suffering from tragically common social and psychiatric disorders.

Nor are survivors, as our amnesia suggests, merely passive or infantile. Every survivor who I have met has thought through the broader religious and cultural dynamics of clergy sexual abuse. Most of them also have a rigorous, critical, and historical understanding of how and why they were targeted as victims. What survivors don’t have is our sustained attention.

Survivors’ actual experiences of clergy abuse are betwixt and between our dominant media tropes. By framing clergy sexual abuse as a battle between heroic journalists and villainous bishops, we are ignoring the much more conflicted and complex experiences of survivors themselves.

Our limited knowledge of clergy sexual abuse has been built on the backs of survivors’ suffering. It is time for us to transform our transient outrage into more sustained support of survivors and their families. This will mean moving away from happier, triumphalist narratives of change and reform, and instead asking survivors how we can help them after the spotlight has moved on.

Brian Clites is an expert in clergy sexual abuse and has spent the last nine years interviewing Catholic survivors in the United States. In his upcoming book, Surviving Soul Murder, Clites explains how American survivors have transformed their suffering into legal and political reforms. Clites teaches religious studies at Case Western Reserve University, where he is also the Associate Director of the Baker-Nord Center for the Humanities.

***

Published with support from the Henry R. Luce Initiative on Religion in International Affairs.