The Power and Privilege of Catholicism in France

Kali Handelman interviews Elayne Oliphant about her new book, The Privilege of Being Banal: Art, Secularism, and Catholicism in Paris

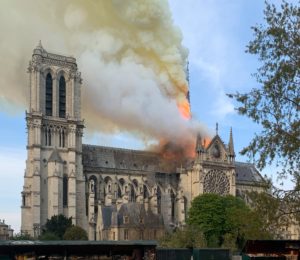

(Image credit: Luis Vazquez/Gulf New)

When you think about religion in France, what comes to mind?

If you’re a regular reader of the news (or the Revealer), your answer likely has something to do with Islam and Islamophobia. I have discussed these undeniably urgent issues with Elayne Oliphant quite recently, but I wanted to bring her back for another conversation now because her just released book, The Privilege of Being Banal: Art, Secularism, and Catholicism in Paris (University of Chicago, 2021), invites us into the subject of French religion and politics from another, crucial angle that warrants attention: Catholicism. In a nation where the dominant discourse has, for so long, been about the separation of church and state, how and why do French Catholics and Catholicism still have so much power — and how is that power evident in Parisian art and architecture?

The Privilege of Being Banal invites the reader into a close-up examination of a big question: Why does France still need Catholicism? Oliphant’s meticulous, sensitive, and incisive ethnographic perspective offers us a way to understand the political landscape in France — the debates that are explicitly about religion, and the ones that aren’t so explicit — in immensely valuable new ways. Oliphant spent two years working at a contemporary Catholic culture space with a lofty mission. Through her interactions with patrons and visitors, and analysis of the exhibitions and events they attended, we begin to see much more clearly how and why French Catholicism is able to move in and out of view in ways nothing — and no one — else can.

Kali Handelman: Could you give us a sense of what the book is about and, in particular, how you define and connect the core concepts of Catholic materiality, banality, and privilege? How do these ideas help us to answer the question, as you put it in the introduction: “Why does France still need Catholicism?”

Elayne Oliphant: I can’t thank you enough for these thought-provoking questions, and for investing so much thought and time in this book over the last few years. You were both a fabulous editor and an important collaborator. I miss walking down our short hallway to interrupt you in your office and share a thought or a quandary. Our conversations have been so vital in this process.

This is a book about how Catholic materiality — the objects, images, and spaces that mediate Catholic practice and fill French landscapes and museums — figures into the reproduction of inequality and of privilege. Initially, I was interested in how Catholicism did not appear to be a “problem” in France. Any writing, scholarly or otherwise, about the appropriate place of religion in France focuses disproportionately on Islam. And yet, so many symbols of France clearly have connections with a Catholic history that remains palpably present — just think of the attention Notre Dame received in 2019. Catholicism has not vanished, but it is taken for granted as self-evident and unproblematic.

This is a book about how Catholic materiality — the objects, images, and spaces that mediate Catholic practice and fill French landscapes and museums — figures into the reproduction of inequality and of privilege. Initially, I was interested in how Catholicism did not appear to be a “problem” in France. Any writing, scholarly or otherwise, about the appropriate place of religion in France focuses disproportionately on Islam. And yet, so many symbols of France clearly have connections with a Catholic history that remains palpably present — just think of the attention Notre Dame received in 2019. Catholicism has not vanished, but it is taken for granted as self-evident and unproblematic.

The common assumption among White, tacitly Catholic French citizens is that France is a truly secular country (unlike, many people explained to me, the United States). Islam continues to appear in French news and political debates because so many French people believe Muslims fail to appreciate and assimilate into France’s “secular” culture. But what these debates and common assumptions miss is how so of Catholicism shapes public life in France — from its national holidays and key national symbols, to the way schools close on Wednesdays in order to accommodate Catholic catechism classes. In order to explain this phenomenon I turned to the concept of banality as developed by Hannah Arendt. Arendt uses the concept of banality to explain, first, how people can come to participate in actions which they would otherwise find problematic, and second, how such actions can come to be accepted as self-evident, both individually and collectively. I use it as a means of explaining how so many in France can both argue for the necessity of Catholic materiality in landscapes, museums, and public life, while also insisting upon France’s unblemished secularity without feeling the weight of that paradox.

In earlier iterations of this book, I relied on the concept of the “unmarked” to describe how Catholicism seems to fade into the background of public life in France. And yet, over time I realized that this concept wasn’t quite right. There are many different theories to help us think through the relationship between partial visibility and oppression, from the invisibility of some minority groups to the hypervisibility of others. Ralph Ellison used the word “unvisibility” to describe the unrecognizablity of Black humanity in the United States. But the relationship between partial visibility and privilege is not as well studied. The privilege of Catholic materiality in France is seen most readily in its ability to move between the background and the foreground, the unmarked and the monumental without causing consternation.

This is the “how” question that the book addresses: “How does Catholic materiality move between the background and the foreground in France?” A brilliant mentor, however, encouraged me to ask and answer another question: why? Why does France still need Catholicism? I am not asking here why some people still “choose” to be religious in a secular age; we’ve long ago rejected the secularization thesis that underlies that query. What I am asking is why does ostensibly secular France still need to do so much to support, expand, and celebrate Catholicism’s privilege?

It is not only the state that participates in these processes — many of France’s richest families gave shocking sums to rebuild Notre-Dame, for example — but the state continues to make choices that elevate Catholic “affordances.” For example, when a commission was formed to address the “crisis” of secularism in France in 2003, it offered numerous recommendations that would have corrected Catholicism’s excessive privilege in French public life, such as including a few holidays of other religions into the national calendar. However, the government refused all of the commission’s recommendations with the exception of one: banning headscarves in schools.

It is not only the state that participates in these processes — many of France’s richest families gave shocking sums to rebuild Notre-Dame, for example — but the state continues to make choices that elevate Catholic “affordances.” For example, when a commission was formed to address the “crisis” of secularism in France in 2003, it offered numerous recommendations that would have corrected Catholicism’s excessive privilege in French public life, such as including a few holidays of other religions into the national calendar. However, the government refused all of the commission’s recommendations with the exception of one: banning headscarves in schools.

So, why does France still need Catholicism? The answer I came to is that Catholicism’s privilege helps to justify the fact that it has never achieved anything approaching the democratic equality imagined in its famed Revolution. France’s Catholic materiality — and, in particular, in medieval edifices — allow French residents to both celebrate the inequalities that were overturned and evade the need to dismantle others. It allows them to make space for some forms of inequality — between Muslims and Catholics, Black and White residents, as well as rich and poor — while celebrating the limited cessation of others.

Moreover, while Catholics are as diverse as any group, with various political persuasions and lifeways, the institutional Church — especially in Paris — has long been associated with elite groups. The privilege of these groups is maintained through this limited equality, which is aesthetically celebrated in part through the country’s Catholic medieval cathedrals like Notre-Dame and innumerable works of Catholic art that populate its museums, such as the Isenheim Altarpiece, and the medieval Catholic imagery that fills its literature, such as in the works of Victor Hugo.

My research focused primarily on how the institutional Church works to reproduce the banality of its materiality — encouraging people to view it as both the natural background of French life, and the marked spaces and objects that stand out and demand attention and support — because this banality secures Catholicism’s privilege. And I found a rather remarkable space in which it had powerfully committed both to amplifying the country’s medieval Catholic materiality and providing a space to celebrate its elite supporters. A few weeks before my research began in 2008, the archdiocese of Paris inaugurated the Collège des Bernardins. A former medieval monastery that had been expropriated by the state following the Revolution, the archdiocese bought the space back from the state in 2001 on the hunch that its very existence could make a powerful claim about the necessity of Catholicism in France in the present.

During its first two years of operation, this claim was made through a variety of elite, bourgeois practices, including contemporary art exhibitions, intellectual debates, and public theology classes. I ended up spending so much time in the space that when additional “mediators” for the contemporary art exhibits were needed, I seemed an obvious candidate.

These exhibits came to be central to my analysis of Catholic materiality because they showed the significant work required to maintain its banality and its privilege. In the inaugural exhibit, for example, an artist shattered row upon row of eight-foot-tall and one-inch-thick glass panels prior to the opening and glued them to the floor, leaving a mixture of jagged fragments and shattered pieces. Along one side of this glass maze, he also burned thousands of books through a technique that allowed the soot to settle in the shape of these books, creating a library of “shadows.” The responses to this exhibit were fierce, with most of the elite public despising it. And yet, they actually had far more in common with the artist than they would have imagined. They had come to this former medieval space looking for a glimpse of what I call “enlivened” medieval materiality — something of the presence of the original site transported into the present. The artist has long maintained a similar approach to medieval Catholic material forms. “If one were to make a hole in the wall of any medieval cathedral, blood would flow” he once declared, while “if one were to make a hole in the wall of a museum, nothing would come out.” Thus, while their goals were similar, the means of how to protect the enlivened value of Catholic medieval materiality was deeply contested precisely because the stakes — the reproduction of Catholic privilege — were so high.

KH: I’d love to hear more about how and why you approached this research ethnographically. In the book you argue that “ethnography does not allow the researcher to inhabit another’s point of view in any straightforward way” but that, instead, it is a way of “paying attention in a particular place and time, allowing the anthropologist to identify continuities, shifts, and contradictions in the social world they encounter.” You then go on to talk about Hannah Arendt’s “insistence that banality is that which lacks depth” and that “we might understand the exclusion that necessarily accompanies privilege as the refusal to imagine the experience of others and, therefore, to deny the diverse complexity of social worlds.” There seems to be a relationship there, something about empathy — about observing and imagining the complex social worlds of others. Do you see a connection between the work of ethnography and the task of critiquing banality?

EO: I’ve been thinking a lot about ethnography lately: about ethnography as a research method, about my own ethnography, about its potentials, and its limits. Ethnography can bring us powerfully into the minutiae of social life and, when applied to religious life, it is most often used to describe and analyze what David Graeber referred to as “density” — the rituals, images, and creative practices through which humans create other-than-human bonds. But Graeber worried that anthropologists’ penchant for density meant that we spent too little time addressing the less thrilling but equally important bureaucratic facets of our worlds. When applied to religious life, I find that this penchant encourages us to protect religious life from real scrutiny and critique. Another way of thinking about Graeber’s argument is to suggest that we need to pay more attention to the banality of religious life.

I realized pretty early on that — due to the elite status of those I was studying and my own lack of cultural capital in France (a problem that is the inverse of the more typical distinctions between anthropologists and their subjects) — I would not be able to access the density of their lives in ways that would allow for any kind of “thick” description. When I met them by attending church events, they tended to be more open to inviting me over for tea and an earnest conversation about the “oppression” of Catholicism in France. At the Collège, however, people rarely introduced themselves or offered any openings toward deeper relationships. My first extended conversation was with a woman who referred to me as “the foreigner.” As time passed and I developed connections with mediators and employees, I became even more invisible to the visiting public as I was clearly a low-level employee, and, even worse, one associated with the exhibits they despised.

At first, this was a source of a great deal of concern, but it did allow me to let go of certain fantasies I might have held about ethnographic research. Graeber has also argued that by paying too much attention to the density of privileged life ways, we may in fact exacerbate the disparities in empathy that have made White, Christian, Western social worlds appear far more human and worthy of celebration than the social worlds of other religious and racialized groups. Conducting ethnographic research among privileged groups, therefore, requires a particular approach. I found I needed to complement participant-observation with extensive study of secondary historical literature and archives in order to be able to push back on some of the assertions made by my interlocutors.

(Interior of Collège des Bernadins)

In something akin to the anthropologist John Jackson’s account of “thin description,” I found I had to turn to a variety of spaces in which claims about Catholicism’s necessity in France were being made, from museum exhibitions (and the history of the creation of museums in France following the Revolution) to works of fiction and political discourse. I tried to analyze the Collège from a variety of different perspectives: those of visitors, volunteers, low-level employees, artists, and managers. I examined Catholic materiality in a variety of different scales, as the basic building blocks of religious life, as a central theme in the European art canon, as objects of destruction during the Revolution, and as objects of transformative revival in French public life over the nineteenth century. I also looked at Catholic materiality through diverse registers, including how it can be experienced, variously, as sacred, enlivened, aesthetic, cultural, and fetishized. The fact that Catholic materiality can exist in so many registers without appearing contradictory is, in this case, an expression of its privilege. At the same time that Catholic materiality is being celebrated in such flexible ways, a variety of Muslim sites and spaces are surveilled and shuttered, taking for granted the singularity of Muslim life as only and excessively religious.

KH: Reading your book I was particularly struck by the tensions around “the medieval.” You write about how, on the one hand, Muslims are accused of being medieval in ways that make them “un-French” while, on the other — and at the same time — the Collège is able to leverage its ancientness to amplify its claims to Frenchness. I’m interested in how this double standard (to put it too mildly), pivots on relationships to materiality generally, and art specifically?

EO: I have continued to mull over this question since handing in the final manuscript. The conclusion I have come to in the months that have passed is that the medieval period is a particularly enticing one because it precedes 1492 and the beginning of Western Europe and the Catholic Church’s long-standing encounter with banality — of living with their most profound contradictions. And here I am not saying that Catholic materiality has become banal due to a process of secularization. Banalization is instead a process of living with and even celebrating practices that contradict how groups perceive themselves. How a place like France could both foreground its revolutionary call for equality and participate so actively in chattel slavery is a powerful contradiction. The medieval period in Europe had its fair share of violence, but a lot of scholars would point to the violence unleashed in 1492 as rather exceptional in human history. The materiality of the medieval period points to a time before European nations were also global empires that engaged in expansive and horrific systems of exploitation. It points to what appears to be a more coherent, innocent time in French history.

In the book, I emphasized how the desire for medieval Catholic materiality has been rather commonplace in France since at least the nineteenth century, and I have become increasingly interested in thinking through how that period coincides with the partial confrontation of the paradoxes of claiming equality while benefiting from slavery in the Caribbean. In light of the discomfort posed by these paradoxes, the attraction of the medieval as the true source of France’s genius — rather than the Enlightenment, Revolutionary, and modern periods in which the banality of these contradictions is written into so many texts, spaces, sculptures, and images — appears newly legible. Numerous paintings found in museums throughout the West, such as the frescos that adorn the rotunda of the old Paris grain exchange, take for granted the less than human status of Black slaves and depict their object status in ways that are deeply banal. In contrast, the material heritage of the medieval period offers a glimpse into a world prior to this history that few in France have shown any interest in confronting.

KH: For my last question, I want to ask something perhaps too broad, but that I imagine readers will really want to know. First, how do you hope your book will help us better understand current events in France right now and going forward? And second, how might we use the “banality of privilege” to think about inequality and justice work in the United States?

EO: I hope my book encourages readers to approach material heritage with a bit more caution. I have a friend who — after I described my book to her — felt the need to tell me that she really loves medieval Cistercian monasteries. I had to chuckle because she was basically saying, “I love visiting these places; please don’t take them away from me.” With apologies to this dear friend, I do hope that we visit those places that call out to us for a variety of complex reasons with a more critical eye. This is not to say that Catholic materiality is only political and serves no other purposes, including religious purposes. Throughout the book, I resist trying to separate out the religious from the political. But it is to say that human relations — productive ones and violent ones — are grounded in material forms, including those we inherit from the past. And I hope my book offers another means by which to ask what kinds of human relationships are being forged in the maintenance and reproduction of these spaces.

The protests in the United States in summer 2020 were largely successful in getting a larger White public to consider how they may have been participating in structures of inequality and engaging in microaggressions. In part, I think, activists were highlighting the banality of the White lived experience in the US: how is it that we are able to live with the incoherence of a country that claims freedom and equality while so powerfully maintaining White supremacy? And a great deal of the focus of these protests came to land on material heritage.

Many similar protests have also been seen in France. On May 22, 2020, in the Overseas Department of Martinique — two days before the re-initiation of Black Lives Matter protests following the murder of George Floyd — Black Martinican activists destroyed two statues of a White abolitionist, Victor Schoelcher. According to a Communiqué, the activists would no longer allow “plantations to erase the memory of our ancestors for the benefit of their torturers.”

In July 2020, an activist with the group “Brigade Anti-Négrophobie” spray-painted the words “state negrophobia” in broad daylight below the statue of Jean-Baptiste Colbert (1619-1683) that adorns the French National Assembly. Colbert was the architect of the “Code Noir” that laid out the laws governing French slavery. The activist’s bold gesture was captured on video, including the moment when two members of the national police rushed towards him, machine guns drawn. As the police jostled him, he managed to offer a remarkable two-minute speech in which he argued that the statue depicted someone who supported “the murder of Black people, the rape of Black people, and the torture of Black people (les noirs).” Instead of stopping this history, he declared, they came to stop him. “Instead of protecting me,” he said passionately, placing his hand expansively on his chest, “you protect these,” gesturing to the statue that rose above them. When one of the police officers began to explain that vandalism is forbidden, the activist argued that “no, it is racism that is forbidden,” and insisted that Colbert was an apologist for “negrophobia.” “Colbert industrialized and institutionalized negrophobia and the murder of Black people!”

In July 2020, an activist with the group “Brigade Anti-Négrophobie” spray-painted the words “state negrophobia” in broad daylight below the statue of Jean-Baptiste Colbert (1619-1683) that adorns the French National Assembly. Colbert was the architect of the “Code Noir” that laid out the laws governing French slavery. The activist’s bold gesture was captured on video, including the moment when two members of the national police rushed towards him, machine guns drawn. As the police jostled him, he managed to offer a remarkable two-minute speech in which he argued that the statue depicted someone who supported “the murder of Black people, the rape of Black people, and the torture of Black people (les noirs).” Instead of stopping this history, he declared, they came to stop him. “Instead of protecting me,” he said passionately, placing his hand expansively on his chest, “you protect these,” gesturing to the statue that rose above them. When one of the police officers began to explain that vandalism is forbidden, the activist argued that “no, it is racism that is forbidden,” and insisted that Colbert was an apologist for “negrophobia.” “Colbert industrialized and institutionalized negrophobia and the murder of Black people!”

I think there are a lot of questions to be asked about the banality of historical objects in French public life and in asking those questions, we can open ourselves up to much broader conversations about the ongoing limits of France’s Revolution, and the persistent myths of its equality. Religious life and material forms should not be exempt from these processes of critique. Just as religious life has always been deeply intermingled with political and economic forms, our attempts to strive toward futures that look very different from our pasts must also include religious actors, institutions, and objects. I hope my book participates in this process in some small way by highlighting how the Catholic materiality we take for granted as unproblematic may at times constrain our ability to imagine alternate futures.

Kali Handelman is an academic editor based in London. She is also the Manager of Program Development and London Regional Director at the Brooklyn Institute for Social Research and a Contributing Editor at the Revealer.

Elayne Oliphant is an Assistant Professor of Anthropology and Religious Studies at NYU. She is the author of the book, The Privilege of Being Banal: Art, Secularism, and Catholicism in Paris, from the University of Chicago Press.