The Name: A History of the Dual-Gendered Hebrew Name for God

A book excerpt with an introduction by the author

The following excerpt comes from The Name: A History of the Dual-Gendered Hebrew Name for God, by Mark Sameth, published in May 2020 by Wipf & Stock (and reprinted here with their permission). The author claims to have uncovered the “lost” name of God, YHWH. Rather than the previously conjectured “Jehovah” or “Yahweh,” Sameth argues THE NAME was pronounced Hu-Hi, Hebrew for “He-She.”

The excerpt comes from the book’s preface and introduction.

***

There are almost eight billion people on the planet now. More than half of them are followers of one of the so-called Abrahamic faiths: Judaism, Christianity, and Islam. That’s a lot of people.

And so the claim at the heart of this book is no small claim. It is positively audacious, even in an interpretative tradition like Judaism. My claim is that the God of the ancient Israelites—the God of Abraham, universally referred to in the masculine today—was originally understood to be a dual-gendered, male-female God. Half a lifetime of research and my own spiritual intuition have led me to this belief. My hope is that you will take this journey with me and judge for yourself.

And so the claim at the heart of this book is no small claim. It is positively audacious, even in an interpretative tradition like Judaism. My claim is that the God of the ancient Israelites—the God of Abraham, universally referred to in the masculine today—was originally understood to be a dual-gendered, male-female God. Half a lifetime of research and my own spiritual intuition have led me to this belief. My hope is that you will take this journey with me and judge for yourself.

The ancient four-letter personal name of God, YHWH, which many Jews refer to in Hebrew as HaShem, meaning THE NAME, or as Bible scholars refer to it, the tetragrammaton, has not with official warrant been pronounced in public for over two thousand years. Along the way, some have guessed that THE NAME might have been pronounced Jehovah or Yahweh. Many more assumed that the pronunciation of THE NAME had been lost forever. But I believe that I have found it and it was hiding in plain sight all these years.

***

How is it even possible that the holy name of God, the four Hebrew-letter tetragrammaton YHWH, whatever it meant and however it was pronounced, became lost? Let me say up front that I do not believe that THE NAME was ever lost, but more likely hidden by a small circle of priestly elites who kept the secret to themselves. We’ll get to the how and why in chapter 2. But first, the official story.

The official story of how and when THE NAME became unpronounceable is found in the Talmud, a compendium of laws, tales, and discussions written down by the rabbis (a class of scholars that arose in the late Second Temple period) over the course of some four hundred years. According to the rabbis of the Talmud, in the early days of Israel, common people pronounced THE NAME in their everyday greetings—certainly until 586 BCE, when the First Temple in Jerusalem was destroyed. Upon the Jews’ return from exile in Babylonia, increasingly restrictive prohibitions were said to have been instituted to guard against THE NAME’s frivolous or profanatory utterance. A new ruling prohibited the explicit pronunciation of THE NAME by commoners, restricting public expressions to the priests, who were said to have stood before the people, proclaiming THE NAME in a loud voice as they blessed them. In time, the priests began to lower their voices, mumbling THE NAME, allowing it to be drowned out by the Levitical choir so as to conceal it from those unworthy of hearing it. Then, with the death of the High Priest Simon the Just (Shimon ha-Tzaddik, ca. 200 BCE), THE NAME was no longer uttered by his brother priests. When the high priest pronounced it on Yom Kippur, he did so inaudibly.

Painting by David Roberts (1796-1849) depicting the destruction of the 2nd Temple in 70 CE

So how did the Israelites refer to God? Outside the Temple, everyone—priests and commoners alike—would, instead of saying THE NAME, employ the respectful substitute name Adonai (Lord). The secret expression of THE NAME was passed on by the Israelite sages to their disciples in Hebrew only once (some say twice) every seven years and was never divulged in commonly spoken Greek. Upon the destruction of the Second Temple in 70 CE, the rabbis no longer permitted THE NAME to be pronounced, other than when being transmitted from master to disciple, by anyone anywhere. Even the substitute Adonai had, by that time, become considered by many Jews too holy to be uttered, other than when one was praying or reading scripture aloud in a public gathering. The substitute HaShem, meaning THE NAME, became a way for Jews to refer to God in their everyday discourse.

Jehovah

But what about THE NAME Jehovah? How and when did that name arise? Why do some people say that was the way the unpronounceable name of God was pronounced?

The Torah was translated into Greek in Egypt in the third century BCE (the first-ever translation of the Torah, a work known as the Septuagint). In time, if perhaps not at first, the word Kurios (Greek for “Lord”) was employed by the rabbi-translators as a substitute for THE NAME.

By the fourth century, the Roman Catholic Church was in need of a Latin translation of scripture. In the year 382, Pope Damasus I commissioned Jerome (later Saint Jerome) to create a standard official Latin Bible. This work—which came to be known as the common translation, versio vulgate, or Vulgate—continued the by-then time-honored practice of employing the term Lord as a substitute for THE NAME. Just as the Greek Bible had used the term Kurios (Kýrios), the new Latin Bible used the term Dominus. Meanwhile, in their public reading of scripture the Jews continued their custom of pronouncing Adonai whenever they came to THE NAME. No one was pronouncing—or attempting to pronounce—THE NAME. Kurios in Greek, Dominus in Latin, and Adonai in Hebrew all mean “Lord.” It seems that the actual pronunciation of THE NAME had been lost.

Sometime between 600 and 800 CE, academies of Jewish scholars known as Masoretes or “Masters of the Tradition” (Ba’alei Masorah in Hebrew) turned their attention to fixing for posterity the pronunciation of the Hebrew text of the Bible as it had come down to them. Hebrew was essentially a consonantal language, and so the Masoretes had to invent symbols—diacritic marks—to indicate the vowels. Those symbols were most often placed underneath the consonants, though sometimes above, to the side, or inside them.

The Masoretes had to decide what to do when they came to THE NAME. Should they, or should they not, write out the four letters of the unpronounceable name? Should they write them out but leave them without vowels? They made an interesting choice: they placed an approximation of the diacritic marks for the word Adonai below the consonants of the four letters YHWH as a mnemonic device intended to remind the reader not to attempt to pronounce the ineffable name but rather to say—in accord with the tradition, which by that time was already of very long standing—Adonai.

In time (we don’t know precisely when), non-Jewish clerics would attempt new translations of the Bible, not from the Greek Septuagint nor from the Latin Vulgate but directly from a Masoretic text. And when one non-Jewish cleric working with the Hebrew text encountered the four letters of THE NAME, he made an understandable mistake: he read the four consonants in combination with the vowels placed beneath them by the Masoretes as a mnemonic for Adonai. And so this cleric believed—quite mistakenly—that he had discovered the original pronunciation of THE NAME: Jehovah.

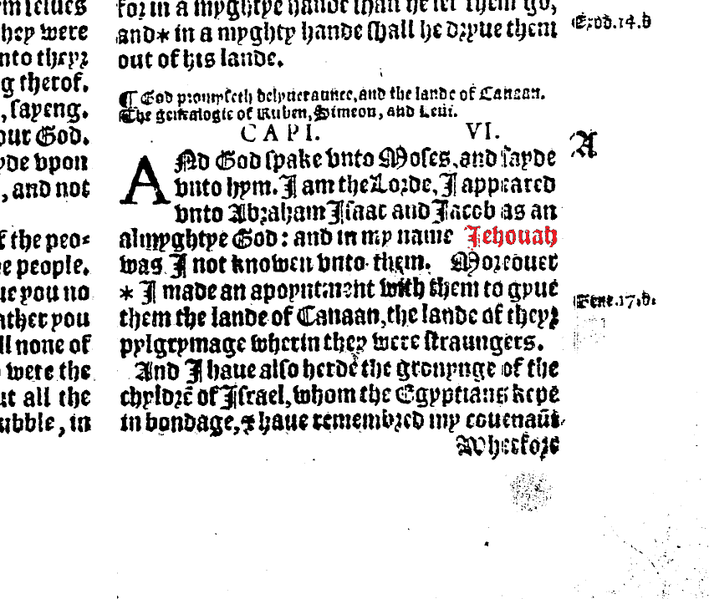

A page from The Great Bible (1540) with “Jehovah” in red

Bible scholars of an earlier generation believed Galatinus (the Franciscan Pietro Galatino) to have been the cleric who introduced the error in his 1516 work Concerning Secrets of the Universal Truth (De arcanis catholicae veritatis). But the error appeared much earlier than that in Porchetus de Salvaticis’s Victory against the Jews (Victoria contra Judaeos, 1303), as well as in some editions of the Catalan Dominican friar Raymund Martin’s work Dagger of Faith against the Moors and the Jews (Pugio fidei adversus Mauros et Judaeos, 1278). Whoever was responsible for the error first, it was, as Robert J. Wilkinson has observed, “hardly an error that needed to be invented, rather an inevitable mistake lying in wait.”

Martin Luther perpetuated the error in his 1526 German translation of the Bible, and William Tyndale did the same in his first-ever direct translation of the Bible from Hebrew into English in 1530. Tyndale’s translation became the basis for the appearance of Jehovah in the influential English King James Bible in the early 1600s. And that’s how the pronunciation Jehovah took hold.

Yahweh

Among Christians, few questioned the rendering of THE NAME as Jehovah until the nineteenth century, when the German Bible critic Heinrich Friedrich Wilhelm Gesenius popularized the hypothesized pronunciation Yahweh in his Hebrew and Aramaic Manual on the Old Testament (Hebräisches und Chaldäisches Handwörterbuch über das Alte Testament). A consensus was never reached in the scholarly community to support this. But Yahweh joined Jehovah as a second conjectured pronunciation.

Mark Sameth, named “one of America’s most inspiring rabbis” by The Forward (inaugural list, 2013), is featured in Jennifer Berne and R. O. Blechman’s God: 48 Famous and Fascinating Minds Talk about God. His published essays include “Is God Transgender?” in the New York Times. His book, “The Name: A History of the Dual-Gendered Hebrew Name for God” was published by Wipf & Stock in 2020.