The Makeup Reformation

Race, representation, and Rihanna in the church of makeup.

People often ask why I choose to write about makeup. Do I really think it’s that important? Makeup is superficial – literally. It is applied with brushes and sponges to sit on the surface of the skin, removed at the end of the day to leave a clean canvas for the next. Yet, the applications of makeup reach far beyond the outlines of the face and body.

I care about makeup because it is yet another institution where, because of the color of their skin, racial minorities are often excluded. The majority of cosmetic companies do not produce complexion products – such as foundation and concealer – in a range of pigments wide enough to work for people of color; most makeup is still made for light-skinned customers. It’s a perhaps subtle, but still insidious, way to perpetuate and uphold standards of beauty that exclude black and brown people.

Makeup matters, then, because representation matters. If commercial standards of beauty can evolve to include spokeswomen of color (Lupita Nyong’o for Lancôme) and men (Manny MUA for Maybelline), why is it still so hard for these companies to produce and market complexion makeup (foundations, concealers, etc.) for its black and brown skinned customers?

I would argue that we can answer these questions by looking at the twin forces of capitalism and religion as they have acted through American history and into the present moment. Here, religion becomes not so much belief and practice, as a way of understanding the ways in which our capitalist society is organized. It is a useful metaphorical lens for understanding how makeup brands can both perpetuate and combat racism.

***

In her new book, Consuming Religion (University of Chicago Press, 2017), Yale University historian of religion Kathryn Lofton explores how we can use religion to understand social life in a capitalist society. She argues that our society is based on producers’ and consumers’ desires and values. Producers of goods and services desire profits and determine the value of their products based on potential profit margins. Consumers can be a little more complex in that they express a desire to acquire those products, but can also express desires to influence certain industries through their purchasing habits: buying more products to support a brand, or boycotting their products when they do something objectionable. In other words, our feelings and political ideals not only shape our consumerist desires and values, but are a source of our power within our capitalist society.

“Corporations inscribe practices and promote worldviews beyond the applied scope of their product,” Lofton writes. These worldviews are the ways in which people conceptualize themselves in a society, a foundation for how they perceive and interact with the world. A worldview can be based on presumptions constructed through our experiences and can guide our ethical (and thus, consumer) judgments. Company employees, are indoctrinated with a perspective that they can then pass on to consumers. For instance, Apple’s corporate culture values simplicity. They instill in their employees the idea that even very advanced technology can be simple. Then, Apple workers create advertisements and work in retail stores, inspiring the same values in their customers. The values and desires of a corporation are meant to impact not only workers, but also the buying habits and beliefs of consumers. But those values are often much more complicated and insidious than just “simplicity.”

Rihanna at the launch for Fenty Beauty

The makeup industry has been shaped by the same white supremacist politics and histories as everything else in America. The lack of complexion products available to suit dark skin is the result of the makeup industry’s worldview. In this worldview white skin is beautiful, makeup is for women and thus, products are made for and marketed to a consumer base of white women. Makeup companies have a very long history of using their influence to further racist logics by which beauty belongs to those who are rich and pale.

For example, one might think of the ways in which paleness has been thought of as synonymous with beauty, and such pale beauty as indicative of purity. In the Victorian era, makeup was mostly worn by noble women. Upper class white women whitened their faces with lead-based powders to further distinguish themselves from lower-class (and enslaved) tanned, black, and brown people who labored outside in the sun. Their whitening complexion makeup also served to distinguish them from actresses and prostitutes whose more obvious makeup, rouge and lipstick, marked them as “impure” and lower-class.

Even as makeup became mass-produced and more affordable in the 1920s, black and brown people were still not given access to the cosmetic tools of white, upper-class beauty. In the early 20th century, the justification was that black women did not have the money to buy makeup. Today, their exclusion has been justified on the grounds that black women, statistically, do not invest in makeup the same way they do in hair.[1]

But the logic here is circular: How can darker complexioned women buy foundations that are not produced in shades that match their skin? Of course they aren’t spending money on makeup if it doesn’t work for them.

Using Lofton’s argument to develop a deeper understanding of why makeup matters, I argue that makeup companies are projecting worldviews which consumers, particularly women of color, are empowered to either literally buy into, or reject. Moreover, as consumers become better able to engage with brands directly through social media and YouTube, new brands are constructing new worldviews.

In other words, there is a schism in the church of makeup and a reformation is well underway.

But let’s expand this religious analogy even further. Where is this church you may ask? The most well-known is Sephora, a cosmetic store chain that sells over 100 mid-tier and high-end makeup brands and has proselytized its way to 2,300 stores in 33 countries. The Catholics: mainstream cosmetic companies like Tarte (more on them in a moment). And Luther reemerges in Rihanna, the popstar from Barbados, and her revolutionary new cosmetics company, Fenty Beauty. Just as Luther used his printing press to spread his message, Rihanna has used a comparably revolutionary new medium, social media — particularly, YouTube — to share hers.

YouTube, as a video-based social media platform, provides a unique online community where subscribers can identify with others on a visual level and companies can literally hear feedback from consumers. The site has become a marketplace of its own, with endless opportunities for advertising and the potential for beauty gurus to become YouTube stars who even make it onto a Forbes list of top beauty influencers.

YouTube is now one of the main ways consumers engage with companies especially through review videos, a popular genre of beauty vlogging that has earned some channels as many as 5 million subscribers. Among these channels is one run by black beauty vlogger Nyma Tang. A Sudanese-American woman with a deep skin tone, Tang is part of a growing YouTube community that has highlighted the demand for makeup suitable for dark and deep skin. On her YouTube series “The Darkest Shade,” Tang tests out the darkest shade available in various makeup products to see if it will match her skin but, like many of her subscribers, she has struggled to find products that work for her. Though the problem is longstanding and persistent, opposition is growing and so is the worldview of this sect of consumers.

In response to their persistent economic and aesthetic marginalization, YouTube has facilitated the construction of an opposing worldview in which women of color can also be considered beautiful people who deserve to have options when it comes to makeup. In Lofton’s terms, makeup YouTubers have clearly stated their desire for an industry that values inclusivity.

There have been attempts to change the industry before. For example, Fashion Fair Cosmetics sold dark complexion products in the 1970s and 80s, proving for the first time that there was a market for them. Brands like Iman and Black Opal have since helped to develop a cosmetics counter-worldview in which black is indeed beautiful. But what YouTube (and the Internet generally) has done is allow consumers to hold mainstream cosmetics companies accountable, pushing them to change their exclusionary practices.

The result is not simply an alternative sect, but a more organized means of critiquing the mainstream. For example, in early 2018, Tarte Cosmetics released their Shape Tape Foundation, a highly anticipated companion to their best-selling concealer. Foundation needs to match skin much more precisely than concealer does, but when Tarte released their new foundation in a range of 15 colors, only three of them were potential matches for medium tan and dark skin tones.

The backlash against Tarte was immediate and the controversy surrounding the product compelled popular beauty influencers to express their opinions, thereby enunciating their desires and values as the makeup industry’s consumers. Even beauty vloggers who could find their shade in the line refused to review the product. Those who were not able to find their shade pointedly promoted other companies. They not only reviewed better foundations, but other makeup products that could replace previously recommended Tarte lines, essentially calling for a full boycott of the company.

Their criticism and activism were evidence of the emerging makeup reformation. Tarte’s whitewashed beliefs and practices served as a modern example for the white-supremacist and exclusionary doctrine of the old makeup world order. And they were resoundingly rejected. It was evidence of a new worldview, and with that worldview, opening up a space for a new kind of brand. A brand like Fenty Beauty.

In her introduction to Consuming Religion, Lofton concisely explains how any product can have profound implications. She writes, “Access to consumer options creates contexts for education, empowerment, and progress.” The creation of Fenty Beauty is just such a new context for educating and empowering marginalized consumers and is a sign of political and social progress for black and brown people.

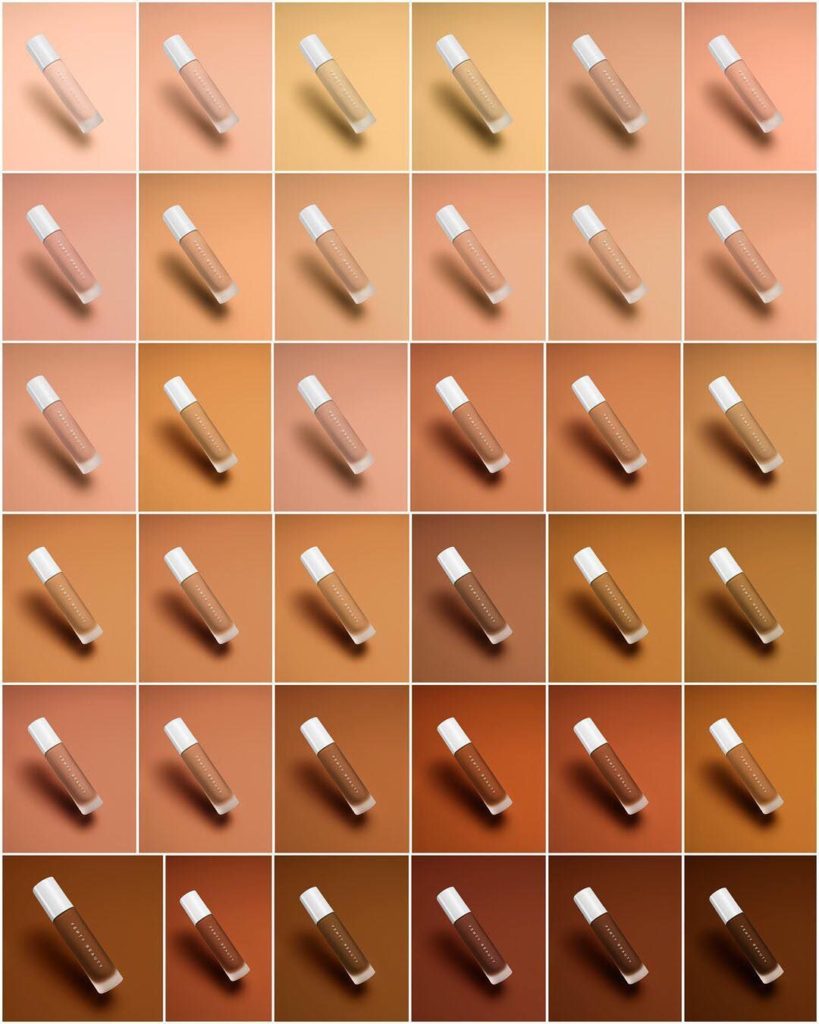

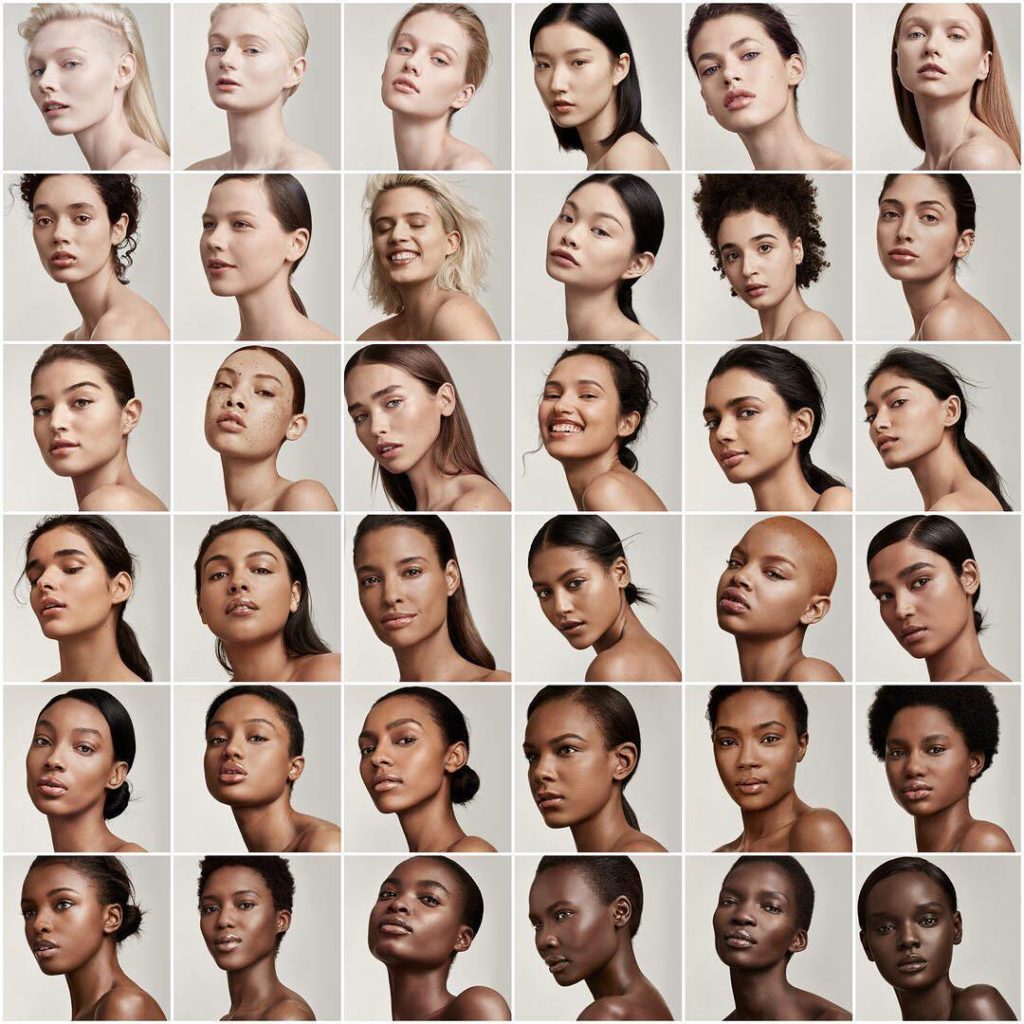

Debuting in September of 2017, the brand catalyzed a major paradigm shift. In its first product release, Fenty Beauty launched 40 foundation shades ranging from very fair to very deep. Compare that to Tarte’s measly 15? The line was instantly iconic. The brand has been at the forefront of defining a new standard of inclusivity in makeup where everyone is accounted for from the very beginning.

In her review, Nyma Tang recounts the excitement she felt when buying her shade at Sephora and seeing so many other people that looked like her find their shade as well. “That’s something I really appreciate. I love the fact that this product was available to so many people so fast.”

Fenty Beauty has been a huge success with a recorded $72 million in earned media value (non-paid advertising) in its first month. It has become an established leader of a new sect and made way for a new future for makeup. The brand has demonstrated that it values the inclusion of men and a plethora of skin tones through its promotional photos and reposts of people wearing their products on Instagram.

Image from Fenty Beauty Instagram

Its popularity has inspired a phenomenon dubbed “the Fenty effect” wherein other brands seek to emulate the same outstanding shade range, but are often still operating without the same desires and values that Fenty Beauty and its consumers both share. Companies such as Kylie Cosmetics and Huda Beauty have been seen by black beauty influencers as not showing a legitimate change in their worldview and rather, as transparently wishing to capitalize on good press solely to generate more profit. They are acting in bad faith, and the consumers have largely rejected them.

Considering makeup through the lens of religion can help makeup consumers understand the changes that are taking place and the power that they hold in affecting those changes. Though makeup is just a small part of the progress that needs to take place regarding race in our society, even the smallest changes can have a large impact. Those who had not previously given the makeup shade predicament much thought may see the industry as a more tangible example of institutional racism that they can literally see in stores; it does not merely exist in the depths of our government or our penal and educational systems. In capitalists societies today today, the power to affect change may not just lie in moral arguments, but also in consumers’ wallets.

***

[1] Nielsen’s 2013 African-American Consumer Report lists ethnic hair products as the demographics’ most purchased category, and points to cosmetics as an area of untapped potential.