The Last Twentieth Century Book Club

Good Ol' Job

The first of an ongoing monthly column, The Last Twentieth Century Book Club, is an exploration of religious ephemera by Don Jolly.

By Don Jolly

*This is the first installment of a new monthly column, The Last Twentieth Century Book Club, exploring religious ephemera *

The religious world, like everything else in the American twentieth century, has produced a vast and unprecedented amount of stuff: pamphlets, comics, Chick Tracts, VHS tapes, videogames and vinyl records. This column, The Last Twentieth Century Book Club, is an exploration of this ephemera in the religious mode. Its aim is to unearth the obscure religious artifacts of my birth century, examine them critically, and open them up to new audiences.

*****

In the early 1970s, Steve Groce (pronounced “Gross”), now a sociologist at Western Kentucky University, was in his mid-teens and living in Greenville, South Carolina. One day, during his confirmation class at Trinity Lutheran Church, Groce first listened to Tim Rice and Andrew Lloyd Webber’s musical Jesus Christ Superstar. “[I was] totally blown away by the album,” he recalled, through our recent correspondence. “At that time, I had also finished 10 years of piano lessons, and had recently taught myself guitar. In addition, I was very ‘into’ the popular singer-songwriters of the day—Carole King, James Taylor, Dan Folgelberg, etc. So, at some point, I began to think some version of the old, ‘Hey, I can do that.’”

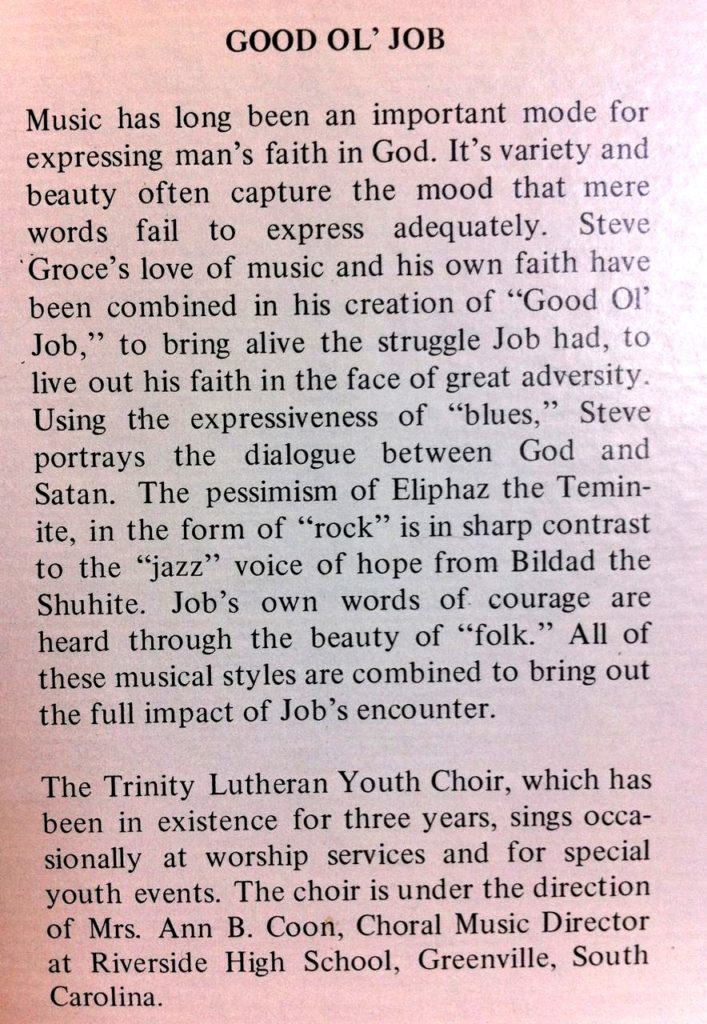

So, he did. Good Ol’ Job, a rock opera based on one of the most wrenching explorations of theodicy in the biblical text, was completed soon after, written by Groce and performed by the Trinity Lutheran Youth choir, under the direction of Ann B. Coon. They took the act on the road, touring Lutheran churches in North and South Carolina one summer, where it was met with rave reviews. An LP version was recorded at Mark IV Studios in Greenville. It was sold at out-of-town performances and through the church office at Trinity. “To my knowledge, [it] was the only record ever made and sold through the Church,” Groce recalled.

I came across a copy of Good Ol’ Job in 2011, in the “oddities” section of Breakaway Records in Austin. Its label, in hasty, confused letters, reads “xtian rock funk?” It cost me seven dollars, and the clerk gave me a look when he rang it up.

Good Ol’ Job is an impossible record. There’s no way it should have worked. Job, as source material for adaptation, is difficult at best. While framed by a relatively simple parable about a righteous man being tested in a game of bets between God and “the adversary,” Satan, the majority of the book is taken up by a symposium on theodicy between the afflicted Job and his friends Eliphaz the Temanite, Bildad the Shuhite, Zophar the Naamathite and (in a section whose provenance is controversial) Elihu the Buzite. Within this material there are two overlapping ideological (and perhaps compositional) strands: the first is the Book of Job the Patient, covering 1:1-2:13, 27-28 and 42:7-17, which contains a Job who refuses to blaspheme, even in the face of absolute despair. The second strand, the Book of Job the Impatient, covers chapters 1-31 and 38-42. In it, Job argues with increasing vehemence that suffering often arrives without moral precondition, that God “destroys the blameless and the guilty” alike (Job 9:22). God, ultimately, agrees — and Job’s doubting cohorts are made to apologize for their presumptions.

Hardly material for light afternoon listening. Groce’s approach, however, does an admirable job of capturing the flavor of the text. The key here is multivocality. As Ann Coon, writing on the back of Good Ol’ Job’s record sleeve puts it:

Faced with a Biblical book largely rendered through dramatic debate, Groce decided to use a variety of musical styles and approaches — from the creeping, bluesy bass line employed to represent the adversary in “God and Satan” and “God and Satan (reprise)” to the rattling, condemnatory rock n’ roll of Eliphaz the Teminite and the bouncy, Kinkesque sound used for Zophar the Naamathite. The highly poetical (and difficult to translate) language of the biblical book is elided, here, replaced by a folksy, unpretentious vernacular in which quotations from the original material are slyly inserted, alongside winking colloquialisms such as God’s offer to “go fly a kite,” if Job blasphemes under Satan’s torture. In both form and content, there’s a sense of play in evidence.

The ultimate effect is disarming and effective. Good Ol’ Job, by virtue of its playful side, treads into some of its source material’s most challenging philosophical waters without collapsing. The structure of the Book of Job is, somewhat, retained, although most of the first side is given over to the background material of chapters one and two. The symposium in the biblical text begins with a speech from Job and then rotates to statements from each of his friends, pairing them with Job’s response. This cycle is then repeated twice, with some alterations (and no Zophar) in the third go-around. In Groce’s version, Eliphaz, Bildad and Zophar are accorded one song a piece — each featuring some of the album’s wildest musical invention, broken up by downbeat, lamenting responses from Job. God, speaking in the fifth track of the record’s second side, “Stand Up Like A Man”, attempts to reconcile the two musical strands by capturing both the cold, desolate tone of Job’s responses and the bombastic explosion of his friends’ critiques. The album ends as it began, with a triumphant reprise of the first track, recounting Job’s return to prosperity.

The nuances of the biblical book’s argument are, of course, somewhat simplified in Good Ol’ Job. The distillation of Zophar, Bildad and Eliphaz’s long speeches into bite-size pop songs, for instance, is openly reductive. Still, the record’s embrace of multivocality through genre leaves its listeners without a clear sense of resolution, or at least, with the tools to resist the resolution provided. While Job does, ultimately, return to God in the album’s penultimate track, “Everything In Heaven is Mine,” the fact that the thorniest issues of the story are posed in musical language wholly distinct from this conclusion leaves the question of theodicy open in the mind of the listener. Groce’s sense of play keeps Good Ol’ Job from turning into a rote and didactic exercise, and his sense of musical invention keeps it from being pat. Ultimately, he turns out an entertaining pop record which also raises complex questions of theodicy without either brow-beating or talking down to his audience. Like I said, impossible.

While he was producing Good Ol’ Job, Groce was also in a series of garage bands. “They never amounted to anything,” he recalled. “It wasn’t until I went off to college that I started performing regularly in ‘play-for-pay’ rock ‘n’ roll bands — a trend that continues to this day.”

“I’m still recovering from the physical demands of playing a four hour bar gig on Saturday night,” Groce told me, in our recent exchange of e-mails. Immediately after the Saturday show, he jumped in the car, making the hour-long drive to Hendersonville, Tennessee “to play the music at my brother’s church at the crack of dawn Sunday morning!” Pop music, for Groce, has never been a problematic addition to his religious practice, although he recalls some mild strain at Trinity over the form of Good Ol’ Job. When it came to pop, young Lutherans in the 1970s “were much more accepting than, say, our Baptist counterparts,” Groce recalled:

“I recall that even in statewide Lutheran youth gatherings, we were playing Three Dog Night’s ‘Joy to the World’ as part of contemporary worship services. It’s probably worth noting that, at least in part because of the success of [Good Ol’ Job], that electric guitars and drums became much more normative during worship services at Trinity [in the 1970s].”

“The reaction to the album was unfailingly positive—much to my amazement,” Groce recalled, speaking of the album’s early days. The first performance, at Trinity, was a blow-out:

“When we finished, of course everybody applauded (the church was absolutely packed). We exited the church through a side door. I was putting my guitar into its case, when [choir director Ann B. Coon] grabbed me and told me I had to go back into the church. When I walked out there, I got a standing ovation—I guess for having written the thing. It was a feeling I’ll never forget.”

It’s not something we should forget, either.

- God and Satan

- If Only My Prayer Could Be Answered

- Zophar the Naamithite