The First Brick at Stonewall

The power of a myth to inspire generations of LGBTQ people

(The Stonewall Inn. Image source: National Park Service)

It’s Pride month, when we commemorate the historic Stonewall Uprising by taking over our local streets in festivals, marches, and parades. Like salmon returning to a natal spawning ground, LGBTQ folks in New York City complete the annual pilgrimage to the iconic site of the 1969 riots, which took place in front of the Stonewall Inn, a queer bar in Greenwich Village. Most of the mile and a half route is an interminable traffic jam on foot, but in the last few blocks the meaning of the march becomes visceral. The barge-like floats peel off and marchers enter a chute of rainbows that extend to the sky, with cheering onlookers waving from apartment windows, fire escapes, and rooftops. Our bodies encrusted in sunscreen and glitter, with sore knees and now-urgent bladders, we tread through the same narrow streets where pride was born.

Along with the rainbows and glitter, there’s also a reliable role in this annual ritual for the killjoy historian. Our role is to comment on the incident being commemorated, the June 28, 1969 protests, when queens, dykes, and fairies resisted what was customary harassment by the New York Police Department. A riot, and a movement, followed. Inevitably, historians responding to the Pride prompt recite a litany of corrections, which establish that all the “firsts” attributed to Stonewall happened earlier and somewhere else: this event was not the first gay riot; not the first resistance to a police raid on a gay bar; not the debut of radical activism; not the moment when the LGBTQ movement burst into public view, and not even close to the wholesale beginning of queer political action.

This airing of historical grievances is more than an annual social ritual; it is the foundation to an entire field of study. According to historian Terence Kissack, “almost the entire corpus of gay and lesbian history can be read as an attempt to deconstruct the Stonewall narrative.” And yet, the intellectual ferment to correct the popular narrative’s inaccuracies have made little dent. Indeed, the appetite for incorrect history seems only to grow more voracious with the conglomerate multinational expansion of Pride. It is in response to this conundrum that queer cultural critic Jasmin Nair counters the rush to remember and commemorate Stonewall with a simple refusal: the energy to remember this one event, she argues, has created a “juggernaut” that has crushed other significant events—from the Compton’s Cafeteria Riot of 1966 and the raid on Chicago’s Trip bar in 1968, to the more than six hundred other queer protests that took place in the United States around the time of Stonewall. To make space for other memories, Nair argues, we should “forget Stonewall.”

As if we could. The pleasure of bad history is hardly limited to Stonewall. Indeed, historical inaccuracy is arguably a qualification for public recognition as a significant holiday. Commemorative status increases in proportion to historical overstatement.

Take, for instance, the most well-known plot point in the popular narrativization of the Stonewall riots: the notorious brick. A key theme in these stories addresses the question of who started it all, distilled into the query, “Who threw the first brick?” The symbolic importance of Stonewall as the place “Where Pride was Born” (as put by the heavily criticized 2015 film Stonewall) means that the instigator of the riots is at the same time a symbolic progenitor of the whole LGBTQ movement: our queer spiritual parent.

Empirically speaking, this quest is at best futile. Riots are by definition chaotic, driven by a collective fury. “Who threw the first brick?” narrows that chaos to the pitching velocity of a single bicep; as if with one well-aimed toss we could, in Dr. King’s phrasing, bend the moral arc of the universe toward justice.

The absurdity of the question serves up history as parody. Social media users have turned it into a comic riff with a fill-in Mad Lib formula: “Name verbed the first noun at Stonewall.” “Jamie Lee Curtis threw the first Activia at Stonewall.” “Lil Nas X threw the first butt plug.” And so on.

No amount of mocking the nonsense of this question, however, will cease its emphatic answers. The names put forward as historic first brick-throwers make an ethical and political point, by spotlighting activists whose identities represent those in the margins of the movement, most frequently key leaders like Marsha P. Johnson and Sylvia Rivera. Each was historically significant for reasons independent from the riots: Johnson and Rivera, both participants in gay liberation and gay activist organizations founded after the riots, co-founded the Street Transvestite Action Revolutionaries and persisted in the political struggle for and by trans people, people of color, and sex workers.

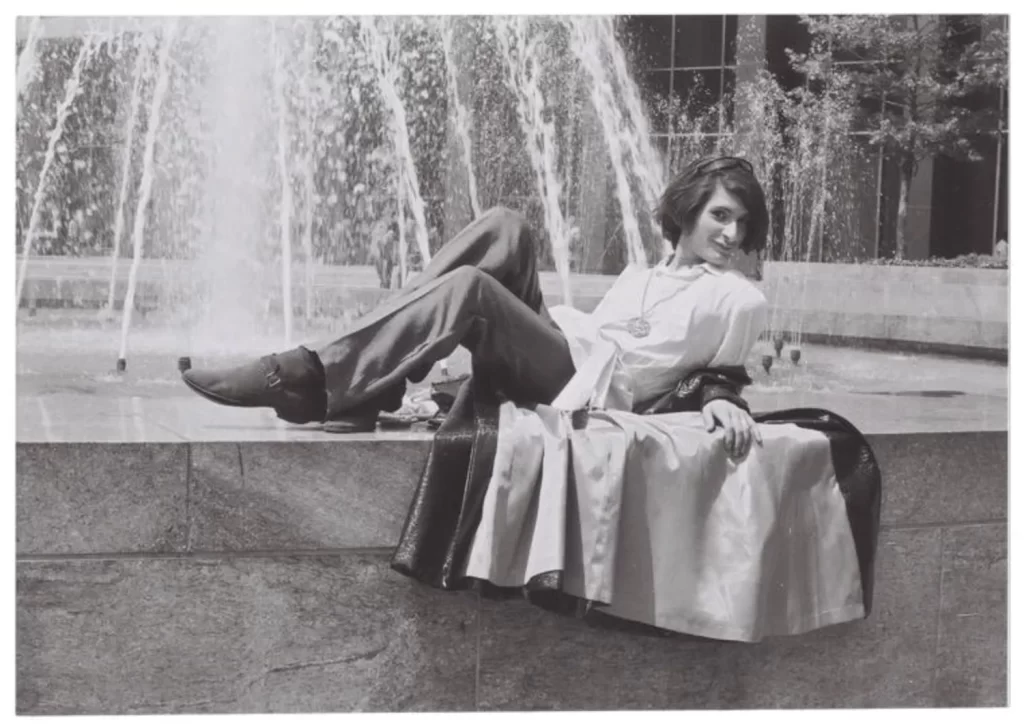

(Marsha P. Johnson. Image source: USA Today)

Neither of them threw the first brick. Indeed, neither credibly claimed this role for themselves. (Rivera, perhaps jokingly, at one point said she threw the second Molotov cocktail; Johnson persistently reminded her friend that neither of them was actually at the scene when the riot began.)

Why are these activists, as transgender people of color, so persistently conscripted into this fictive role of brick-thrower? Addressing this puzzle takes up a different question than what happened at Stonewall: why have queer communities become so passionately invested in fictional answers to a counterfactual question? Perhaps an investigation into how this question came to be asked will illuminate what is so fiercely at stake in its answer.

Among the puzzles of Stonewall’s popular narrativization is how a brick came to replace the historically documented projectiles. Documenting “firsts” in a riot is difficult under any circumstances, but this riot was better documented than many others. Two Village Voice reporters, Lucian Truscott and Howard Smith, witnessed the unrest in real time and published side-by side accounts the following week. Truscott reported from the streets outside the bar. Smith, whose beat that night was to follow the officers of the First Division, retreated for safety into the bar along with the cops. Both accounts are riddled with homophobic slurs. In the eyes of the reporters, as well as the police, the scene was full of ordinarily dismissible “limp wristed faeries” suddenly turned implausibly terrifying. Despite their failure to recognize the humanity of the protestors, the two authors quite convincingly document the objects being thrown at them.

It began with small coins: pennies and dimes, which then escalated to nickels and quarters. The question never asked about Stonewall is “who threw the first penny?” A penny is an unimpressive weapon on its own, but imagine fistfuls of spare change spewed from an angry crowd. Like buckshot, it forced the arresting officers to retreat into the bar for cover.

Reporter Smith, barricaded in the bar, could not see what was being lobbed at the windows and door. Truscott, perched on a trashcan outside, kept a close log. Coins spent, the rioters scrabbled for heavier objects: beer cans, bottles, and cobblestones. Eventually, Truscott’s trashcan was commandeered, as was an uprooted parking meter, which became a battering ram against the door—the cause of the frightening sounds heard from inside the bar. No bricks. Also, no Molotov cocktails. Smith witnessed how the bar caught fire. An arm reached through the shattered front window to squirt a stream of lighter fluid into the room, followed by a lit match.

Truscott and Smith’s accounts of the riot were, in the early 1970s, a routine part of gay newspapers’ June special editions for what was then called Christopher Street Liberation Day. Nobody asked in those days who threw the first brick, but the accounts were often framed with an acknowledgement that “drag queens” and “street kids”—always nameless—were the vanguard in that night of struggle.

The first named projectile thrower at Stonewall came not from memory but from fiction. Patricia Nell Warren’s novel Front Runner, published in 1974, scripts in this role a hunky white athlete: Harlan, a former college athletic director who was fired after being outed as gay, is now a high-end hustler in the Village. Warren narrates the importance of the riots through Harlan’s eyes: “An amazing thing happened. I had a rock in my hand and I threw it […] Something cracked in my head that night, and in the heads of the gays. That night saw the coming of the militant gay.”

Warren’s book was surely not the only source for the unanswerable question about the first projectile. But when asked, in the decade following, it was usually in the form of “who threw the first rock?” The typical response to the question was to insist on its impossibility while also insisting that “youth and drag queens” led the way—not the Harlans of the world. And yet, it was often the Harlans of the world, in the form of prominent white cisgender gay men, whose reminiscences most formatively shaped narratives about Stonewall. Vito Russo, film writer and gay activist from New York, echoed a familiar refrain in his reminiscences about Stonewall in Army of Lovers: “Drag queens,” he insisted, started the Stonewall riots “because they really had nothing to lose. They threw the first rock.”

By the 1990s, a brick had come to replace the rock in the stories about Stonewall. Gay academic Martin Duberman’s book on Stonewall helped to cement in place the existence of a brick-thrower (even if that person remained unknown and unnamed). Duberman’s interview with Sylvia Rivera also lifted her up as a participant in the riots, who recalled throwing “bricks and rocks and things” after the riot was already in full swing.

(Sylvia Rivera. Image source: Kay Lahusen)

What should be clear in this account is what today’s social media users already know: the question about the first rock-cum-brick is part of a formula. The answer follows an established pattern. Calling out the formulaic nature of this exchange might seem derogatory in ways similar to naming parts of Stonewall a “myth.” This is what the historical corrections miss: it is precisely as a myth, and one that is ritually enacted, that the Stonewall narrative holds power. Its mythical quality is a problem only if accuracy is the only test for truth.

To distinguish between truth and accuracy is to acknowledge that a story’s power to move can be separated from the factual information it conveys. Myths ground us in a glorious past with brave forbearers who we can call upon when we are beleaguered. They offer more than historical information; they envelop the listener into the frame as participants in the action.

Stonewall has continued to hold power for LGBTQ communities facing violence and marginalization, with the first brick-thrower standing in as a symbol of a movement against injustice led by those who were most stigmatized and rejected. American national mythology has many such figures—from Tisquantum (known as Squanto) to Rosa Parks—whose roles are narrated through a combination of social marginalization and heroic exceptionalism. Taken as history, these stories offer discrete points of information that erase the collective struggles and continuing oppression of the communities these figures represent.

Correcting the facts of these histories may be a futile effort. But perhaps we can refocus and expand the way these narratives work as mythology. If our myths invite symbolic identification with the most marginalized, they should compel all of us into the struggle with these communities.

Factually speaking, “who threw the first brick” has one answer. Myth has no such constraints: the truth of this question is not to inform you. The truth of this question is to recruit you to the fight for all trans and queer lives.

Heather White is the author of Reforming Sodom: Protestants and the Rise of Gay Rights.