From the Margins

The False Gods That Changed My Mind

Christianity’s attempt to silence the voices within its texts mirrors the way some Christians have tried to silence the voices of real people throughout history

(Image source: Illustration by Rick Szuecs for Christianity Today)

Many years ago, I was wandering around the Oriental Institute at the University of Chicago when a pair of idols caught the corner of my eye. Passing the Lamassu, the immense Neo-Assyrian winged bull with a man’s head carved into limestone, I walked over and stood in front of a display, towering over two little men.

A gold man on the left was sitting, staring back at me with two empty eye sockets. One hand was chopped off. The other looked like it was holding a ping pong paddle. He was wearing a tall, funny hat, but had a superbly lined goatee. His eyebrows and lips were resting in a look of disappointment or senile exhaustion. The legs formed a perfect 90 degrees, draped in a skirt, resting on what previously must have been a throne but was now a wooden block that was part of the museum’s display. His chest was crumpling like an autumn leaf.

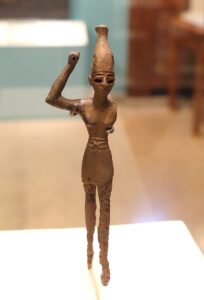

To the right of the gold man, there was a smaller, rusty figurine. He also had empty eye sockets, a missing hand, actually a missing arm, a slightly pointier hat, and a skirt. But this one looked like a younger man. He was shirtless, revealing ripped pectoral muscles. And he was standing—leaning forward with one leg in front of the other—raising his right fist in the air. The closed fist had a circular hole in the middle, the kind that my childhood action figures had for placing guns or lightsabers. Maybe this guy once carried a sword?

I looked down and read the descriptions at the bottom of the display.

21. Late Bronze Age II, ca. 1350-1200 B.C.

The conical hat on this seated figure identified it as El, the creator deity and supreme patriarch of the Canaanite pantheon. Cast in bronze and covered with gold leaf, this statuette is an idol of the type forbidden by the much later Hebrew prophets.

22. Late Bronze Age II, ca. 1550-1200 B.C.

This bronze figurine is believed to represent the Canaanite god Ba’al Hadad, son of the supreme deity El. Ba’al Hadad, identified as the god of fertility and storms, was among the most prominent of the Canaanite deities.

As a Christian, I had always been curious about these idols. I had read about them in the Bible where God’s people often cheated on him with idols like Ba’al. But this was the first time I had seen such false gods up close.

(Ba’al. Image source: Wikipedia Commons)

I was a freshman when these idols serendipitously entered my line of sight. During my first semester at Calvin College, I took a course that covered premodern history and art. I remember being happy when I learned that the course included a free field trip to a museum in Chicago. At the time, I was an evangelical Christian, wrestling with my faith as I became exposed to a more critical approach to understanding religion in the classroom.

Our class made the day trip from Grand Rapids to Chicago midway through the semester. Neo-Gothic towers protruded around the Oriental Institute, and red and yellow ivies devoured its somber stone walls as if it were a site of sacred skeletal remains, simultaneously dead and alive. The only thing I knew about the University of Chicago before this trip was that the fictional character of Indiana Jones was once an archeology professor and “obtainer of rare antiquities” there.

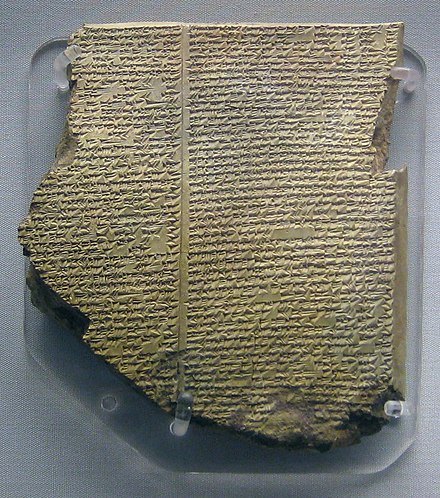

The Oriental Institute was founded in 1919 and its museum opened in 1931. This was after the upstart field of biblical archeology had become all the rage. In 1872, George Smith, a curator at the British Museum, made an announcement he believed would confirm the Bible’s history and shake the entire world. He had deciphered a recently discovered Assyrian tablet—a fragment from the Epic of Gilgamesh—that appeared to corroborate the historicity of the Genesis flood narrative. Smith allegedly went into a frenzy after he made his translation, jumping and stripping off his clothes in front of his colleagues.

Soon after, the British, the French, and eventually the Americans, entered an archeological race to excavate and acquire items in the Levant. At first, some archeologists thought they would prove and flesh out the historical narratives in the Bible. For example, the Bible talked about Jericho’s walls falling. And here were archeologists uncovering the ancient ruins of the city of Jericho. Over time, however, the mounting evidence created a more complicated picture of ancient Israelite religion, one that ran against traditional assumptions.

I wasn’t aware of this history when I stepped inside the sterile air of the Oriental Institute’s museum. Even the irony of its name—which enshrined a mistaken point of view, like Christopher Columbus discovering “Indians” in the Caribbean—didn’t register for me at the time. Instead, I burst into laughter and mocked the deities from behind the plexiglass. Shaking my head, I muttered to myself how silly it was that people could ever worship such things.

I thought about the story in 1 Kings where the prophet Elijah confronts the prophets of Jezebel, who was King Ahab’s pagan wife. Elijah preached that Yahweh, and Yahweh alone, was to be worshipped. The royal court sends Jezebel’s prophets, 450 devoted to the god Ba’al and 400 devoted to the goddess Asherah, to Mount Carmel where they engage in a prophetic duel with Elijah while a mob looks on. They kill two bulls, lay them side by side, and pray to see which God will miraculously burn their bull with fire. Ba’al’s prophets pray but nothing happens. Elijah prays and fire comes down from on high, consuming his bull. Elijah then orders the mob to seize the prophets of Ba’al and he slaughters all of them.

Although idolatry, technically, means the worship of idols, I had learned from Christian preachers to see idolatry in today’s world as existing beyond just physical deities. Idolatry could also mean pursuing the perfect body or securing one’s worth in wealth. But for me, nothing compared to the concreteness of coming face to face with idols that had been buried under thousands of years of dust.

We drove back to Grand Rapids in a crammed, 15-passanger van, and I remained transfixed on those two devilish figurines. They were testaments to humanity’s blindness. Like the Bible said, these idols had mouths but couldn’t speak, and eyes but couldn’t see.

***

I remember choosing Calvin over other Christian schools like Liberty University or Moody Bible Institute because I wanted a rigorous liberal arts education and not fundamentalist smoke and mirrors. I wanted to be Christian and cultured. At the time, Calvin’s faculty had a broad ideological range that included professors who were open to questioning the Bible. I didn’t mind the challenge. My faith still allowed me to absorb what I was learning. The Bible remained infallible in my view. I saw the evidence presented to me as validating it somehow.

As with any ambitious survey course, the premodern class felt like a sprint from cave paintings to the Renaissance. In the first weeks before the trip to Chicago, the art portion had me completely out of my element. I was drowning in slideshows of images I needed to memorize names and dates for, and every other woman or feminine statue was named something-something-Venus. The history portion on the “Ancient Near East” fascinated me. This is where humans invented the wheel, where the Sumerians created writing, where one of the earliest human civilizations blossomed, straddling the Tigris and Euphrates rivers, flourishing for three thousand years before Christ. Babylon, the ancient city-state located in this region, was also where Daniel, the Jewish prophet my mom named me after, came of age.

I took a special interest in this part of the class because the assignments directly related to the Bible. Professor Lim highlighted the parallels between the first chapters of Genesis and the much older Epic of Gilgamesh and Enuma Elish.

(Epic of Gilgamesh. Image source: Wikipedia Commons)

I asked questions about the bizarre giant beings that appear right before Noah begins to build an ark in Genesis 6.

“Who were the Nephilim and where did they come from? What happened to them during the flood?”

Professor Lim sighed, taking one step forward and bringing his fingertips together in front of his gut, hands rocking as if in some frustrated prayer.

“We can’t take Noah’s flood narrative in Genesis as providing reliable information about events in history.”

Another boy, turning slightly red, mustered: “Why can’t we trust what the Bible says about the flood?”

The conservative students in class were now taking risks, getting close to disrupting the elaborate dance we all did not to say or write anything that would step on our professors’ sensibilities in our march toward getting A’s.

Professor Lim was a charmer with slick black hair. He occasionally dressed down in a University of Michigan hoodie to remind others, or perhaps himself, that he had toiled away at a dissertation in Ann Arbor and survived to teach students like us. Sometimes he spoke to our class as if he were texting a friend. When the blond girl who sat in the front row would speak up, he’d say, “Ohhh, Meegaan,” in a Valley Girl accent. He entertained our thoughts and entertained us even when his questions drew blank faces. One day, he pointed at me while doing a slideshow on Late Antiquity. “Wow, Daniel. You have an eerie resemblance to Ambrose of Milan!”

But on that day in which we discussed Genesis, Professor Lim sounded stern. I wouldn’t blame him if he was annoyed. Many of us were accustomed to literal interpretations, but he wanted us to look at the Bible like any other book.

“The biblical writers didn’t simply record revelation that fell from the sky, but they wove narratives that had emerged from their surrounding culture.”

Back then, I quietly judged Professor Lim to be a liberal, the kind of academic who didn’t uphold the faith of Christian orthodoxy. He didn’t value the authority of Scripture as much as I did, but I thought he sounded smart and confident in his grasp of history. I figured I could still learn from him. I was open to conceding that the early parts of Genesis were metaphorical. The stories about Abraham and Moses were still historically accurate, right?

We soon learned the Babylonian tales of Gilgamesh and Enuma Elish, and I digested them as foils to the truth.

The Epic of Gilgamesh may have been a gripping story about queer love, grief, and the failed quest for immortality—with a minor flood-related subplot. But I latched onto the diluvian character of Utnapishtim and saw any similarities he shared with Noah as proving a) the biblical narrative’s grounding in some real event, and b) the superiority of Noah’s story.

The Babylonian creation myth, Enuma Elish, may have shown that the first chapters of Genesis were written in polemical dialogue with other creation myths. But, in my eyes, Genesis was still the true myth. If the biblical writers’ narrative reflected their surrounding culture, then God must have helped them shape the right narrative. Humans weren’t an afterthought for gods who fought and slept with each other like these other stories claimed. We were the pinnacle of creation, made in God’s image.

***

In 2019, a decade after my field trip to Chicago, I read disturbing reports about a Christian zealot who stole carved statues of Pachamama and threw them into the Tiber River. The statues, representing the goddess mother earth in Latin America, were a gift that Indigenous people presented to Pope Francis during the Amazon Synod at the Vatican. At another point in my life, I might have applauded this young man’s act. He later uploaded a confession on YouTube and claimed to be rooting out idolatry and protecting Christianity’s purity. When I saw the news, my heart sank in the way it does for people who hurt themselves, for those who destroy the very planet that gives them breath. Then, I remembered how I had taunted El and Ba’al at the Oriental Institute. They had been haunting me ever since.

(Pachamama. Image source: Paul Haring for Catholic News Service)

I used to see Christianity as bestowing an identity that trumped all cultural allegiances. But as I got older, I started to wonder why Christianity became so good at perpetrating racism. I began to explore my own identity and to imagine who my non-European ancestors may have worshipped before converting—or being forced to convert—to the Christian faith. From this vantage point, the Canaanite idols eventually took on a different appearance.

In those intervening years, my questions changed. I went into college wanting to become a popular Christian apologist like Tim Keller. My goal was to prove Christianity’s superiority. I had no interest in issues of “racism” or “diversity.” In fact, during my first year in college, I decided to live in a residence hall community for those pursuing academic honors. Out of the 40 students, almost everyone was white except for me. I didn’t want to be known for playing race cards but wanted to blow people away with my brilliance. My objective was to transcend identity, storm the heights of philosophy and theology, and earn the simple honorific of “Theologian” just as Aristotle earned the nickname “The Philosopher” in the eyes of Thomas Aquinas. My post-racial pretensions, however, quickly came crashing down. Even if I wasn’t interested in racism, I learned, over and over again, that racism was interested in me.

Someone drew Nazi swastikas in my dorm during my freshman year. The community’s common space had a table wrapped in white poster paper where people would doodle, leave notes, and write immature jokes. When I was coming back from class one day, the table was bare, and the floor was abuzz with whispers that someone had drawn swastikas. The RA had quickly taken down the poster, but it wasn’t clear who had drawn the symbols. I became the most vocal community member to call for further investigation and consequences. Some people around me openly defended it as “freedom of speech” and accused me of overreacting. I felt abandoned by the silences of my peers.

I intimately sensed a chasm. No matter how Christian I was or how much my theology resembled theirs, I wasn’t white. These sorts of incidents shifted something deep within me. I became less interested in proving Christianity’s sound doctrine to others than in asking how Christianity can be used as a weapon to justify oppression. Before college, it was easy for me to exoticize white people. The Long Island neighborhood, public schools, and churches I grew up in were heavily Black, Latinx, and immigrant. During my late teens, I emulated my favorite Christian rappers, from Cross Movement to Flame to Lecrae, ferociously consuming and referencing the work of white Calvinists from a segregated distance. But when I saw the social and political fruits of that ideology at close range, I was horrified.

Those feelings stayed with me and then boiled over when the vandal desecrated the Pachamama statues. It held a mirror to my confusions. In my early 20s, I still wanted to rescue a pure and pristine Christianity from the clutches of white supremacist malpractice. As a person of color, my initial protestations against racist Christians were about being included in Christian supremacy, not about fundamentally altering it. I wanted to believe that the problem with the fruits had never infected the roots. I wanted to redeem the master’s untainted tools.

The more that I read, the more I grew frustrated. It’s hard to protect Christianity’s purity because such purity is an illusion. What would this religion be without the influence of Jews, Babylonians, Egyptians, Persians, Greeks, and Romans? If you want peace, there are verses for that. “They shall beat their swords into plowshares and their spears into pruning hooks.” If you want war, there are verses for that. “Beat your plowshares into swords, and your pruning hooks into spears.”

The charge of idolatry that I relished using against others like the worshippers of Ba’al, I later realized, is one that can easily be turned against me and against people of color. Historically, white Christians have demonized the spiritualities of people around the world as idolatrous. You want to smuggle in some Platonism, thinly veiled white barbarian solar holiday, or the Easter Bunny? No problem. Something revered by a non-European or melanin-endowed ancestor? Heretic!

My questions about Christianity, racism, and colonial violence kept growing as I progressed through undergrad, then divinity school, then a life of independent research and writing. It was this problem that drove me to revisit the biblical story of the ancient Israelite conquest of the Canaanites. I wanted to understand how Exodus’s God of liberation could turn around and become the God of genocide. In the process of writing on that, I learned that the story about the Canaanites was close to the hearts of modern Spanish and British colonizers who warmly cited it as they shed human blood in the Americas; for them, Native Americans were like Canaanites. Years ago, I reduced the Canaanites to one-dimensional villains who bowed before idols; I took the violence enacted against them in the Bible to be just. Now, I wanted to learn more about these El, Ba’al, and Asherah worshippers.

***

When I sifted through the prevailing critical scholarship on the Canaanite conquest story, it overturned everything I thought I knew. The ancient Israelites never carried out a genocidal campaign against the Canaanites like the book of Joshua says. According to the archeological, genetic, and even textual evidence within the Bible itself, the Canaanites were not wiped out. In fact, the Israelites were essentially a subset group of Canaanites, and shared their culture and religion. The fight between the Israelite one true God, Yahweh, and the Canaanite idols El and Ba’al, was more like an ongoing family dispute.

Why would the Bible include a conquest narrative that presented Canaanites as foreign idolaters who were slaughtered by the Israelites? This narrative was likely invented by polemical writers to provide a founding myth about the settling of the “promised land.” Once a militant, Yahweh-only group of Israelites became more powerful, they wanted to prevent others from returning to older Canaanite customs. Monotheism, the belief that only one God exists, was a later development. Most of the Hebrew Bible promotes monolatry, the worship of one God among many. For example, Psalm 82 says: “God has taken his place in the divine council; in the midst of the gods he holds judgment.”

The Israelites denounced by the prophets for worshipping idols weren’t pursuing foreign gods as much as returning to old ones. But the old gods indelibly shaped the new god. Before God reveals his name as “Yahweh” to Moses, he is called “El.” El is often combined with another title such as El-Elyon, or God Most High. In the development of the biblical canon, the two names—Yahweh and El, which reflected two local deities within the region—eventually became interchangeable. They came to be identified as the same deity. The language and imagery of the Canaanite gods was absorbed. Yahweh is an “ancient of days” sitting on the throne just like the aged chief god of the Canaanite pantheon, El. Yahweh is a warrior and rides the clouds just like Ba’al. It’s “syncretism” all the way down.

The Canaanite legacy also extends beyond male gods. While Yahweh occasionally adopts the feminine imagery of motherhood, fertility, and breasts in the Hebrew Bible, traces of the goddess Asherah, the consort to El and sometimes Ba’al, are wiped out in the text. She is only mentioned when the prophets condemn Israelites who still worship her. Yet, an excavation in the Sinai desert that started in 1975 found evidence that suggests ongoing local worship of Asherah as Yahweh’s consort. Archeologists discovered a pottery sherd bearing an inscription about the blessings of “Yahweh and his Asherah.”

I spent four years at a liberal arts Christian college, three years at a divinity school, and no one bothered to tell me that God had a wife.

Orientalism is often presented as a problem of sight. Through its gaze, Westerners construct an East that’s inseparable from their prejudices and the assumptions of their own superiority. My old Christianity was also a problem of sight. My Christianity depended on being superior to every other story. It was a matter of spiritual conquest, not dialogue or exchange. Breaking out of this mentality required me to wrestle with the Bible and to accept it for what it is, not for the idealized constructions people want it to be. Otherwise, I’d see only what I’d want to see, whether that’s the one true narrative or a social justice textbook.

The historical-critical method, like museums and the discipline of archeology, has its racist and colonial baggage. Astonishingly, the Oriental Institute is still named the Oriental Institute. But asking people to choose between faith and the historical contextualization of religion is a false dichotomy. I’ve found that critically studying religion has only expanded my spirituality and my openness to the mysterious workings of the universe.

Christianity’s attempt to silence the voices within its texts mirrors the way some Christians have tried to silence the voices of real people throughout history. But the bodies buried beneath the texts linger. They leave traces of cultures that have stubbornly refused to be completely erased. And people continue to find meaning and inspiration for resistance even in the most problematic of sources. This messy history doesn’t disprove God, or something larger and sacred about this universe, as much as it disproves a rigid faith that’s ill-equipped to encounter surprises.

El. It’s a word I run into all the time. Pedestrian. In Spanish, it’s the definite article: the. El. I hear it and think back to the little gold man I mocked in Chicago. One of the easiest ways to see his legacy at work in the Bible is through its use of theophorics, or God-bearing names. Israel means “El wrestles.” Samuel means “El has heard.” In Hebrew, Daniel means “My judge is El.” I guess I know who’s having the last laugh.

Daniel José Camacho is working on a book about Christianity and the colonization of the Americas with Avid Reader Press. He has previously been a contributing opinion writer at The Guardian and an associate editor at Sojourners.