The Death and Life of Ivan Illich

A pilgrimage to the renegade Catholic priest’s grave to find inspiration on how to resist fascists today

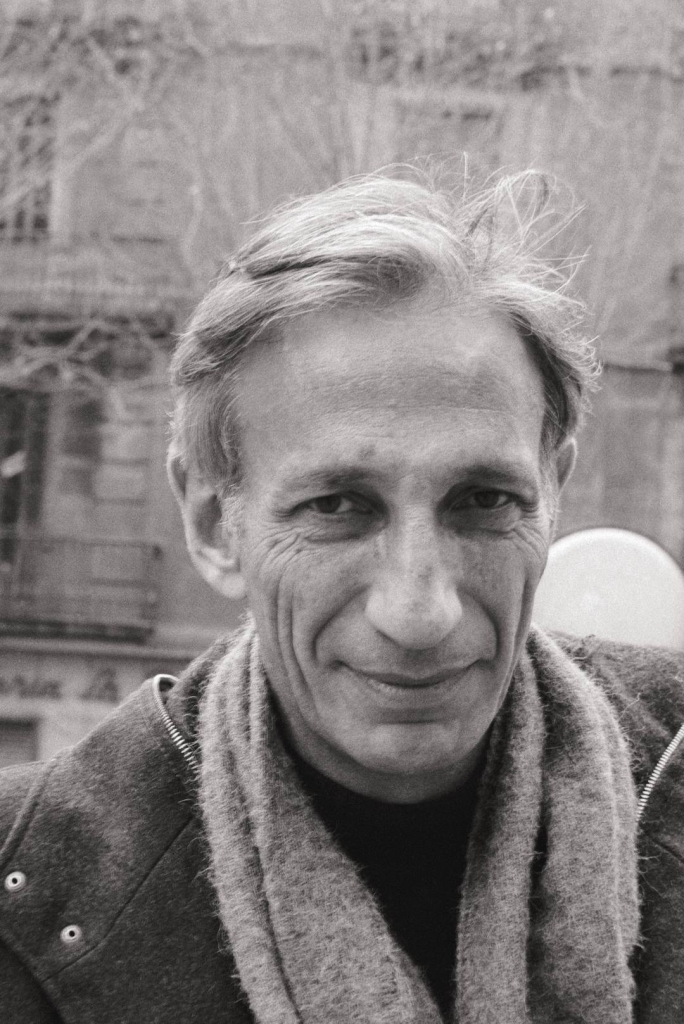

(Ivan Illich. Image source: Manhattan Institute)

Was it an angel or demon who had possessed me to leave home on a pilgrimage in search of Ivan Illich’s grave? Many people know Illich as the author of clever books that asked hard questions about the true meaning of education, transportation, and medicine. Today, Illich has become an important figure for a surprising range of people—libertarians, conservatives, and queer anarchists like me. Personally, I think of Illich as a folk saint and hero. He was a renegade Catholic priest, who fought the Nazis as a boy, and who went on to challenge the Church. He stands as a model of how to resist authoritarianism, and how to live in genuine intellectual and spiritual friendship in the midst of oppression.

Illich often eschewed modern conveniences. Fittingly, the internet provided me with no photos of his grave (and mysteriously, some rumors suggest that the grave is empty, and that perhaps Illich was actually buried in Germany). As I looked around the graveyard, I felt like I had died and gone to some kitschy, Mexican heaven. North of Cuernavaca, the panteón is like a mini pueblo of pocket-sized casas and micro-churches. Fuchsia, lime, mustard.

I didn’t find Illich’s tomb under an altar with other dead priests, because, in 1976, Church inquisitors grilled Illich on trumped-up charges. They didn’t have the nerve to defrock him, but Illich gave up his sacerdotal duties. Soon he boarded up the research center that he had run for a decade in Cuerna. These stories drew me to Illich as an exemplar of someone with integrity and grit, someone who had stood his ground in the face of repression.

After his inquisition, Illich turned to writing books. About how cars sometimes trap us in traffic. About how hospitals sometimes spread infection. About how degrees sometimes make us dumb. His most controversial argument: how the Catholic Church, during the late Middle Ages, had corrupted the teachings of Christ by trying to institutionalize morality by codifying love through monastic rules, government laws, and formal hospitals, imposing charity through institutional disciplines—and how this corruption led directly to modernity’s horrors.

This argument has been turning in my mind lately, and compelled me to find his grave. Recently, I had begun to re-read my favorite books by Illich because I hoped he could help me make sense of the current political turmoil. And beyond the political, Illich had also believed strongly in intellectual friendship, and I prayed his wisdom could help me understand a great personal pain. Sadly, a close friend—a fellow gay man, and fellow convert to Catholicism—turned into a right-wing propagandist (similar to many others on the Catholic right who have become enablers of fascism). I wondered if a pilgrimage to find Illich could help me come to terms with this heartbreak and offer me a guide on how to face fascism today.

***

Illich’s life is like a parable: the king, who became a servant. Born in 1926 to an aristocratic Catholic family—with Jewish ancestry—Illich grew up in a Viennese palace. Fleeing Nazi persecution at 16, Illich used forged documents to hide out in Italy. Illich joined the resistance, wheedling secrets from German officers. After the war, Illich pursued a doctorate in medieval history at the University of Salzburg. He was ordained in 1951 as a priest and served his first Mass in the Roman catacombs.

When I converted to Catholicism in 2017, Illich’s example showed me that I could conscionably join the Church as a gay person. Illich, a scholar of medieval theology, had argued emphatically against the Church’s reactionary sexual-politics. He wrote that the Church’s shrill opposition to abortion, and its repressive stances on sex, had only taken hold late in history, in the modern period.

Later, Illich successfully undermined the misguided policies of three popes. I saw in Illich a model of someone who loved God so much that he devoutly risked disobeying the Church. Illich proposed that such tensions fully expressed Christ’s call to love. I took Illich as a license to believe I could join the Church without becoming, like the cliché, a zealous convert.

But now, I was having zero luck, looking for Illich’s sepulcher among the thousands of purple houses, orange-sherbet chapels, and pink Barbie Dream-Homes for the dead. I crossed myself before a statue of Nuestra Señora. But the winding, two-hour bus ride from Mexico City to Cuerna had given me a belly ache. Before I developed a method for my investigation, I needed to find a baño.

Sometimes the Lord afflicts his favorites with mysterious ailments. Illich refused to treat the tumor that engulfed his cheek so he could learn from his suffering. Maybe my sick stomach corroborated Illich’s arguments against automobiles. But what really made me feel nauseous was my increasingly conflicted relationship with the Church. Because ever since I had found out how my friend Stephen betrayed me—by becoming an anti-gay propagandist—my guts retched.

***

I met Stephen ten years ago across the street from the Empire State Building, shortly before I converted. We were eating breakfast with other graduate students, after going to Mass in Midtown. In those days, the hip, Catholic youths in New York were reading Illich, and trying to practice his teachings on conviviality. Stephen and I recognized one another as two peas in a queer-Catholic pod. Both of us were gay writers in our early 30s. But we approached our sexuality very differently. Stephen believed strongly in the Church’s opposition to gay sex. I believed, like Illich, that these teachings were impracticable and reflected distortions that emerged late in Christian history.

At the time, I was in the midst of writing a dissertation about Saint Paul’s theology of circumcision, and I was drawn to Catholicism through my research, and through my overall disaffection with WASP society. As Joseph Bottum has written, in the U.S., Catholicism is the fastest growing religion among the college educated, partly because it is countercultural and has such a robust intellectual tradition.

Stephen had also only recently joined the Church. We bonded over interest in Illich, and our favorite movies by Pasolini and Coppola. I never took our political disagreements seriously, because I saw Stephen—who is younger than me—as a little brother. In his op-eds, as in his conversation, he often talked about race and ethnicity in weirdly exoticizing ways (insisting, for example, that all Greeks are inherently dramatic like Sophocles, and that all Black people know how to dance because of their DNA). I guess I hoped that he’d grow out of these bizarre opinions, which, of course, all sensible people understand as racist pseudo-science.

Stephen became my godfather, partly out of convenience (because he was my only male Catholic friend) and partly as a camp joke (because it seemed kind of funny to us). At my First Communion, we giggled in the pews. It wasn’t so cute, though, when Stephen tried to shame me. One morning at breakfast, I told Stephen about my first confession. The priest had instructed me not to fret about being gay (“If you have sex with love,” the priest said, “it’s not a sin.”) Stephen pronounced the priest a fraud. Defensively, I countered that Stephen’s own celibacy was a lie.

I knew that Stephen’s therapist had encouraged him to try masturbating. “He suggested,” Stephen told me, “that I should put a carrot in my anus.”

What young homosexual, I wondered, has not put a vegetable in his butt?

Stephen, it seemed, hated his therapist, and hated my confessor—hated anyone who encouraged pleasure—and ultimately, he came to hate all of liberal democracy.

None of this gossip would be relevant to the questions of the day—or to Illich’s philosophy—except, of course, for the horrifying fact that so many sexually uptight, recent converts to Catholicism are enabling the global rise of fascism.

As the Times has reported in multiple articles, in New York City, right-wing Catholicism is a growing movement among the city’s well-educated young professionals. Many chic yuppies were attending Latin Mass. It’s now fashionable for white guys to convert to Catholicism (like me and Stephen, along with Rod Dreher, Sohrab Ahmari, and J.D. Vance).

Catholicism seems to draw new converts from the well-educated because it has a strong intellectual and philosophical tradition. For the bros of the alt-right, some versions of Catholicism also offer a cover for their own reactionary and patriarchal political beliefs and outsized need for order and control.

Curiously, the new Catholic right habitually cites medieval theology to promote fascistic forms of government. They argue that society should return to a medieval-style feudal order, in which everyone is subordinated in a pyramid structure (the king under God, and the people under the king). This is not an accurate understanding of medieval society, which was actually very anarchist with many overlapping legal systems that did not cohere into anything like the unity the right now imagines. But it has not stopped Vance, for instance, from insisting that sympathy for immigrants is a moral perversion, because—in his facile reading of Augustine—true freedom, he says, means obedience to an idealized hierarchy. At the time Vance made these remarks, then-Pope Francis rebuked him. But Vance’s right-wing appropriation of the medieval Augustine belongs to a much larger movement that idealizes feudal hierarchy.

Rod Dreher is perhaps the most well-known figure in this movement. His best-selling book The Benedict Option argues that Christians should retreat from the modern world—especially because of its tolerance for homosexuality—and bunker down in all-Christian communities. Dreher says he modeled his plan after the medieval monasticism of Saint Benedict. But historians have pointed out that Dreher, like other right-wingers who appropriate the Middle Ages, know very little about medieval realities. In Dreher’s historically inaccurate fantasy, he suggested that a return to the medieval feudal order—of kings, monks, and serfs—would enable humans to experience true freedom. Because, as he claims, “freedom” actually means “servitude” to God and freedom from modern liberal society’s “slavery” of sexual vice.

Illich arrived at different conclusions about freedom, modernity, and love. Illich argued that love is not conformity to order, but a free choice of the will to follow its desires. Whereas today’s right-wing Catholics fetishize medieval monasticism and serfdom, Illich argued that these structures had erred because they tried to codify love as a rigid set of rules; in other words, governments and institutions that try to enforce morality are too impersonal to express the passion and personality that are the cornerstones of Christian ethics. Illich further insisted that modern people had amplified this corruption by using the state to enforce morality and order. But Christ, he said, calls us to love in a way that is spontaneous and passionate. Trying to enforce this love, whether through bureaucracy or the market, harms the freedom that is necessary for real ethics.

***

As Stephen’s pundit career took off, I congratulated him. But I rarely read his articles. He seemed to repeat half-baked ideas he borrowed from Camille Paglia about how gender is an unchanging metaphysical truth, and how race and class are intractable problems of the human condition.

Maybe I was in denial, but I wanted to believe Stephen was being taken advantage of—another example (along with Paglia, Andrew Sullivan, and Milo Yiannopoulos) of how gay people can become famous if they carry water for the right. I tried not to take it personally when Stephen published an essay about why divorce is evil. I tried to tell him about how my mother and I—like many women and children—had suffered horrific violence from my father, who on a couple of occasions had nearly killed me. It hurt me that Stephen perpetuated stigma around divorce, instead of defending the rights of women and children to separate from abusive men.

But for a time, I gave Stephen the benefit of the doubt. I knew his essays were a defense against his own shame. Stephen often told me that he resented his own father for being weak and ineffectual, and that he had experienced his parents’ divorce as horribly painful. If he colluded with a right-wing party that wants to put strict limits on divorce—as Project 2025 has outlined—this was Stephen’s way of seeking out a strong father figure to reassert the order and discipline that his own life had lacked. And if he wrote articles undermining trans civil rights, or smearing the legacy of AIDS activists, then I suspected he was covering up his own complexes, and hiding behind Catholic doctrine like a fig-leaf. He inveighed in print against queer and trans people, but he had turned into a whore—prostituting his pen. Insisting on a fundamentalist reading of Original Sin, he viewed human beings as vile—and he set out to prove it by betraying his friends.

Still, it was easy to overlook Stephen’s nasty publications because he described them as ironic poses. His articles, he said, were insincere affections. Really, who could take seriously anyone who praises Donald Trump as a “prophet who has celebrated lies in order to shed light on truth?”

But then, the full force of Stephen’s cynicism finally hit me in the stomach when I discovered that he had printed an essay suggesting that HIV/AIDS is nature’s punishment against sodomites. I almost threw up.

Most of my closest loved ones live with HIV. Due to noxious slander, they suffer intense discrimination. Stephen had picked a fight, and he had forced me to pick a side. I could not speak to him again until he had first issued a lengthy retraction.

As Bertrand Russell pointed out, decent people cannot dialogue with fascists, because fascists do not operate in good faith but undermine the very basis of dialogue. Stephen, like many on the right, smears his opponents with lies and mocks civility as liberal affect. He abuses queer and trans people by insisting that basic decency is “moral decadence.” He sneers at reason, and denounces the Enlightenment, while defending his own illogic as “metaphysics” and “mysticism.” In effect, he resorts to an old bag of cynical tricks that makes it impossible to communicate.

With similar tactics, the inquisitors tried to tear down Illich. But Illich—through years of resistance—had become “wise as a serpent.” And he provides a model for all of us trying to resist authoritarianism.

***

After his doctorate, Illich trained to become a Vatican diplomat. But in 1951, a visit to a Puerto Rican barrio in Manhattan converted him to another mission altogether. The archdiocese mistreated Puerto Ricans, Illich believed, and he dedicated himself to ministering to them.

In that same Manhattan neighborhood, Stephen and I used to pray at the shrine of St. Francis Xavier Cabrini. In the chapel, Mother Cabrini’s body rests in a glass casket. We would kneel there, shoulders touching. Later, when Stephen launched a hipster Catholic website, he commissioned me to write a piece about Cabrini. He has since deleted it from his website.

After Illich’s successes among the Puerto Ricans in New York, he was appointed in 1956 as vice-rector of the Catholic University of Puerto Rico. On the island, however, Illich again confronted the Catholic hierarchy—this time, more controversially.

In Puerto Rico, the Church had formed a political party in order to quash reproductive rights. Illich spoke out against the Church’s intention to use party politics to enforce restrictive sex laws. He was canned from his position.

Around this time, the Church hatched a plan to train tens of thousands of gringo missionaries and to send them to Latin America to combat communism. Privately, Illich lambasted the plan (a “crusade” that “had to be stopped”). He also criticized USAID (launched by JFK in 1961 and currently under attack by the Trump administration). Illich believed that both projects were imperialist.

Surprisingly, as the Church set into motion its missionary plans, Illich arranged to become director of the same missionary-training program he opposed. In 1961, Illich opened up his center in Cuernavaca. Ostensibly, the center would teach Spanish to would-be missionaries. “I did my best,” Illich later acknowledged, “to keep development-obsessed do-gooders out of Latin America.” At the center, Illich subjected his charges to an anti-colonialist pedagogy. He challenged his students so intensely that many dropped out in despair. Despite complaints to the Vatican, the center operated for ten years.

Illich sometimes asked his students if they could love an indigenous Mexican “for what he is, or do you love God in him?” As Illich insisted, “If you love him because you love God in him, you are wrong. There is no worse offense!” Illich contended that love is not some kind of abstract moral code that one must obey, but a free expression of desire—passionate and specific—for the particular individual, and not for “God in him.”

In Cuerna, Illich brought together the left-wing Catholics who developed Liberation Theology, a form of Catholicism associated with Latin America that argues Christians must address social and economic injustice. In 1984, the Church declared this movement heretical (in a ruling authored by the future Pope Benedict).

Illich himself had never exactly subscribed to this school of thought, but he did agree that Latin America needed its own particular theology, especially to counter the U.S.-sponsored development that was causing vast inequalities. On one side, he said, development in Mexico had robbed many peasants of their basic capacity for subsistence and forced them into the capitalist economy. On the other side, he said, consumerism had destroyed old life ways and made the landscape tacky and vacuous.

As my bus trudged through the center of Cuerna, I could see why Illich had picked the city for his center. Cuerna is overrun with chain stores and highways—like a U.S. suburb—and Illich, an opponent of colonization and gentrification, believed that, here, his center couldn’t do much damage.

***

Google Maps shows the location of Cuerna’s gay sex clubs. There’s one in the center of town: an outlet of the Erotika franchise, which has locations all around Mexico. In Erotika, I knew there would be mazes of booths, lined up like confessionals, with small holes between the booths. Maybe I would visit the Erotika after the graveyard.

A taxi driver ushered me into his cab and asked if I liked books. As we cruised along one of Cuerna’s interminable freeways, the driver told me that his aunt had done housecleaning for Erich Fromm, the author of many books.

Fromm had also escaped the Holocaust, wound up in Mexico, and sometimes taught at Illich’s center. In his book Escape from Freedom, Fromm suggests that the historical shift from the Middle Ages to modernity had produced personalities prone to authoritarianism. In Fromm’s analysis, middle-class right-wingers feel afraid of modern liberty because their own economic status depends upon a combination of social and sexual oppression. The bourgeoisie, Fromm said, acquired power by keeping its subordinates in place and by maintaining strict individual discipline (repressing sexual pleasure in favor of a rigid work ethic). Fromm suggests that authoritarians are constituted by repression; they therefore experience liberty as threatening. Fromm theorized that cases like Stephen—along with Dreher, Vance, and Ahmari—are so scared of actualizing their own desires that they need a dictator to dominate them.

Right-wing Catholics often justify their political theology by arguing that, due to Original Sin, we need to be brought to heal by a strong government. Of course, this demonstrates a lack of faith. Free Will comes prior to Original Sin, and, as Illich explained, love is a free choice.

Practically, Catholics who flirt with authoritarianism are making the same error as Christians of the 1930s, like Pope Pius XI, who made a Faustian bargain with Mussolini. The pope assumed Mussolini would promote a more Catholic culture by imposing moral hygiene. He realized too late that the Duce had played him for a fool.

Illich pointed out that, sometimes, people with good intentions actually act as “pawns in a world ideological struggle” and serve as the “lackeys” of wicked empires. “Self-deceived,” Illich called it.

Suddenly the taxi driver pulled over and wished me good luck, dropping me off in front of the graveyard’s gate. I ran through traffic across a double-blind curve. Wafting in the wind was the savory smoke of carne enchilada, grilling at a road-side taco stand. But I felt no appetite. Stephen’s bilious words kept churning back up.

***

I am walking aimlessly in the graveyard. I check again, under that altar with the dead priests, and I meander along the pathway, to the end, where I stand face to face with a cinder-block wall. Beyond is an alley. Banana trees and cramped houses. Heaped up in a pile is a graveyard of another kind. The spiny bones of dried roses. The husks of old marigolds. The glass shards of broken votives, whose candles had long since burnt out. Many visitors to the graveyard have tended the graves of their loved ones.

Please, may the Virgin help me to turn back to Illich, and to find his grave, because that is why I wanted to go on this journey—to write an essay for Illich—and not to write a polemic against Stephen.

My “godfather”: I remember that scene in The Godfather, Part II when Michael tells his younger brother Fredo: “You’re nothing to me now. You’re not a brother, you’re not a friend. I don’t want to know you or what you do.”

I turn away from the wall. And then, there it is. Hand-written black letters say: IVAN ILLICH. The cross is simple, wooden, and conspicuously unlike the extravagant tombs. Covered in weeds, the only adornment on Illich’s grave is one of those little plastic sleeves from an icee-pop.

(Ivan Illich’s grave. Photo by A.W. Strouse.)

There is no beatific vision. No miracle to fling me into the seventh heaven. On the contrary, the sight of garbage on Illich’s grave hardens my heart. An angry epiphany, I realize: I am a childless, gay gringo, alone in Mexico, and when I die, no one will tend my grave either. Certainly, no one will place my corpse inside of a reliquary casket in a gilded chapel and say I was a saint. The pain in my stomach is no divine gift, but a festering, venomous hatred for an enemy whom—despite the Lord’s teaching—I cannot bring myself to love.

Illich’s life and teachings show that it is inhumane to love people by “seeing God in someone.” Love means recognizing each person as they really are—even if who they really are is a sorry Judas, who takes 30 pieces of silver to publish vicious lies.

As Illich has taught me, my calling is not to forgive those who collaborate with authoritarians. My calling is to sweep away this garbage on his grave, and to walk along the highway, past the abandoned gas station, in search of flowers for him. And when my stomach feels better, I will go and eat some of those tacos of carne enchilada, and I will take the bus home to Mexico City. But not before, by the grace of God, I stop at the Erotika.

A.W. Strouse, Ph.D. is the author of Form and Foreskin (Fordham University Press) and The Gentrified City of God (punctum).