The Cross and the Clinic

Religious leaders, like Reverend Elinor Yeo, and their work to provide safe abortion access to thousands

(Image source: Charles C. Peebles/Anadolu Agency for Getty Images)

What if we looked at faith as the cornerstone of the abortion clinic, rather than the rock hurled through its windows? This different angle of vision would bring into focus religious leaders and people of faith who helped make abortion possible by building clinics from the ground up in the years immediately after Roe v. Wade.

As sectarian abortion bans take effect across the United States today, I want to share one such story about the Reverend Elinor Yeo and the abortion clinic she ran in Milwaukee, Wisconsin in the 1970s and 1980s. Reverend Yeo’s decades-long service in support of reproductive rights reveals an important and often overlooked truth: in towns and cities across the United States, the history of abortion providers and their clinics is a story of devotion and faith.

Reverend Elinor Lockwood Yeo spent her life ministering to others. After graduating from Smith College (BA 1955), she pursued a Masters of Divinity at Union Theological Seminary (MDiv 1958), where she was one of four women in a class of 100. The following year, she became an ecumenical scholar at the World Council of Churches (1959). Yeo did not seek ordination as a minister. Instead, she began working as a chaplain at Boston University, where she offered spiritual and emotional support to students. There, she met the Reverend Richard Yeo, whom she married in 1960. In 1968, with their three children in tow, the Yeos moved to Milwaukee to serve in campus ministry together. “A good counselor,” she once stated, “is able and willing to take a person where he or she is without a lot of presupposition where they ought to be.” This same attitude shaped Yeo’s abortion ministry.

When Reverend Yeo arrived in Wisconsin, abortion was prohibited except to save the life of the mother. As a result, many women with unwanted pregnancies had to seek out assistance from illegal, and often dangerous providers. Yeo remembered speaking with these women and learning about the perils they faced. “What impressed me the most was, first of all, how shameful people made women who had abortions to feel,” she declared. “Secondly, how very scary it was to go off on your own, and in many cases, they had to go alone to another city in secrecy… in order to have an abortion. It just did not seem right.” Recalling these facts in an interview half-a-century later, Yeo’s sense of upset was still tangible. “It just seemed to me to be so incredibly unfair for these women to have to sneak around, be driven, blindfolded, in taxis to an upper floor somewhere where they weren’t sure whether the person doing the abortion was a doctor or not,” she told me. “It was a terrifying experience.”

Reverend Yeo was not the only person-of-faith troubled by the injustice of abortion laws and the harms they caused. By the late-1960s, as Jewish and mainline Protestant denominations called for the repeal of restrictive abortion laws, some clergy engaged in direct action through groups like the Clergy Consultation Service on Abortion (CCS). Founded in 1967, the CCS openly defied abortion prohibitions and helped tens of thousands of women with “problem pregnancies” obtain legal and illegal abortions.

(Image source: The Pluralism Project at Harvard University)

Yeo wanted to join a CCS branch in Wisconsin but could not do so unless she was ordained. In Yeo’s words, “all of us had to have ordination status because we could protect our clients by saying that [if] they came to us…we could not reveal what they had said to us.” At a time when elective abortion was illegal in most states, and when prosecutors could treat abortion counseling as aiding and abetting a crime, being a minister offered a legally protected form of speech—what was called “clergy-penitent privilege.” Reverend Yeo’s desire to help abortion seekers through the CCS prompted her to seek ordination in the United Church of Christ in 1970.

Becoming a minister plunged Yeo into the activities of the newly founded Milwaukee branch of the CCS and into the world of reproductive rights activism. Through the Milwaukee CCS she joined a group of Protestant ministers, Jewish rabbis, and one dissident Catholic nun, in helping women obtain safe and affordable abortions. “I will never forget the time that the telephone rang first thing in the morning,” she told me. “My name was on the on-call list for the Clergy Service, and the person said, ‘Hello, is this Reverend Yeo?’…This was like a week after the ordination, and I thought…’This is really important’.”

As local newspapers covered the Milwaukee CCS, Yeo stepped into the spotlight and attached her name to notices in the University of Wisconsin, Milwaukee’s newspaper that read: “Problem Pregnancy? For abortion counseling & referral call Elinor Yeo.” Word quickly spread about the Milwaukee CCS and the group received approximately 3,000 phone calls and assisted 1,200 women in its first year alone. Yeo recalled helping girls as young as 13 and women well into their 50s. She marveled at the fact that so many Catholics sought the CCS’s aid—one year saw Catholics comprise upward of 70% of Milwaukee CCS clients—despite the fact that the Catholic Church officially opposed abortion and described it as murder.

In contrast, Yeo’s theological beliefs about abortion, which viewed the fetus as potential life but not as a person, were in lockstep with mainline Protestant and Jewish thought. “As a Christian minister, the most compelling reason why I regard abortion as a morally acceptable medical procedure is that I believe the Judeo-Christian tradition affirms the primacy of the human spirit over the biological processes of nature,” she told a reporter at the Milwaukee Sentinel in 1971. Her experience as a mother who planned her own pregnancies— “I knew the responsibilities and the challenges of young children” —strengthened her feelings about reproductive freedom and responsibility. Reverend Yeo was emphatic that, “The only person who can decide about this pregnancy is the potential mother.”

(Photograph of the Reverend Elinor Yeo, courtesy of the Yeo family)

For the next three years, Yeo assumed a leadership role within the Milwaukee CCS as its secretary. She organized the activities of her fellow clergy while helping abortion seekers avoid predatory backstreet butchers, the exploitative for-profit referral services in Wisconsin, and the fly-by-night abortion mills in New York State that emerged after abortion laws were repealed there in 1970. After two court decisions made it possible for physicians to provide abortions in Wisconsin after 1972, Yeo also helped abortion seekers to navigate the bureaucracies of abortion clinics and hospitals in Milwaukee and Madison. And she saw first-hand the pitfalls and potential of non-profit clinics that were being established alongside of these other enterprises. All the while, she continually spoke at public forums and debates about the urgent need for abortion rights.

In January of 1973, when the Supreme Court decided Roe v. Wade, religious leaders supportive of reproductive rights in Wisconsin hailed the decision even as they imagined new possibilities for reproductive healthcare services. Looking to the future, the Wisconsin CCS issued a press release stressing the need for “high-quality, low-cost medical care” and “effective compassionate, supportive counseling” that would allow for careful decision making “without coercion.” And it was to these causes—providing low-cost and compassionate abortion care—that Yeo would devote herself for the next decade-and-a-half.

Roe allowed for the expansion of abortion services within hospitals and also enabled the creation of freestanding abortion clinics. In 1975, The Ladies Center (later renamed the Milwaukee Women’s Health Organization), a newly formed abortion clinic in Milwaukee, hired Yeo as an administrator. Reverend Yeo quickly became the director of this out-patient abortion clinic, which offered free pregnancy testing, abortion counseling, and referrals. And she applied her faith-based commitments and ethos of pastoral care to this enterprise. “Abortion should be a matter of conscience,” she explained to the Milwaukee Sentinel in 1975. “I feel a very strong pastoral concern for the people who come here.”

Reverend Yeo’s pastoral concern was apparent in the day-to-day operations of the Milwaukee Women’s Health Organization (MWHO). This clinic served a patient population of teenagers (50%), Catholics (50%) and African-Americans (20%). Many of these clients were poor. Yeo once explained that the clinic was “busiest when welfare checks come in.” Yeo and her counselors aimed to guard against coercion and to make sure patients came to the clinic voluntarily. In that spirit, Yeo and other counselors informed patients about alternatives to abortion. And to ensure informed consent, the clinic counselors asked patients to review and sign forms stating, “I have been informed of agencies and services available to assist me to carry my pregnancy to term should I desire… The nature and purposes of an abortion, the alternatives to pregnancy termination, the risks involved and the possibility of complications have been fully explained to me.”

By centering her patients’ lives and experiences, Yeo further demonstrated her ethos of pastoral care. “Each woman who comes to us has her own story, her own reasons,” Yeo wrote in the magazine Christianity and Crisis in 1986. She wanted her readers to grasp the concrete situations that underpinned women’s choices to terminate a pregnancy:

“We frequently see young women like Anita, the 19-year-old mother of a four-year-old who has enrolled in the local technical college to learn data processing so that she can leave the welfare rolls; or Mary Jo, so abused by her father that she has been in and out of four different foster homes since she was 12. Or Kim, just 12 years old and pregnant after she was raped by her mother’s boyfriend…

In recent weeks we have seen Jill, who has been hospitalized for five months for severe post-partum depression; Anne, a 47-year-old grandmother who had undergone a tubal ligation 14 years ago; Jackie, undergoing radiation treatment for breast cancer.”

The protests outside of Yeo’s clinic began within six months of its opening. Protesters showed up every day bearing signs decrying abortion as murder. Sometimes protesters would bang their signs, emblazoned with graphic images and religious slogans, on patients’ car windows. These early protests were tame compared to what followed.

As segments of the anti-abortion movement became frustrated by their inability to re-criminalize abortion, they became increasingly radicalized. From their perspective, abortion was an ongoing mass murder that called for direct intervention. Abortion services, as a result, became more precarious. An article in the American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology recorded the “epidemic” of anti-abortion violence in the United States between 1977 and 1988. There were reports of “110 cases of arson, firebombing, or bombing…. 222 clinic invasions, 220 acts of clinic vandalism, 216 bomb threats, 65 death threats, 46 assault and batteries, 20 burglaries, and 2 kidnappings.” Violent protests, clinic invasions, bomb threats, and constant death threats shaped Reverend Yeo’s life and caused her clinic to become more like a fortress. “We had so many bomb threats that we had our own ATF agent,” Yeo told me. Daniel Maguire, a Catholic theologian supportive of abortion rights documented the signs of the ongoing siege in 1984:

The clinic door still had traces of red paint from a recent attack. The door was buzzed open only after I was identified…. A sign inside the front door said, “Please Help Our Guard. We May Need Witnesses if the Pickets Get Out of Control. You Can Help by Observing and Letting Him/Her Know if You See Trouble.”

The persistent protests and harassment were not confined to MWHO. Anti-abortion activists called Reverend Yeo’s home every night around 2:00 AM to harass her. But Yeo was not cowed, nor was she alone when facing this adversity. When abortion opponents announced their plans to picket Yeo’s home and leaflet her neighborhood, members of her church, as well as her neighbors rallied around her. Yeo recalled:

“When the protesters arrived, of course they didn’t like the fact that there were church people sitting up on the steps watching them…Before long, the neighbors started arriving, waving these leaflets, and they were furious. They never came back to our house again. Only one time did they come. It wasn’t working very well for them. I just didn’t want them to dig up our flowerbeds. We had some tulips out there, that’s where they were, marching around in the flowers.”

Such intrusions into her home life and her clinic were stressful and took a toll on her health. But publicly, Yeo put on a brave face, telling the Milwaukee Sentinel, “We sat out on our front porch and watched them. They strengthen my resolve.”

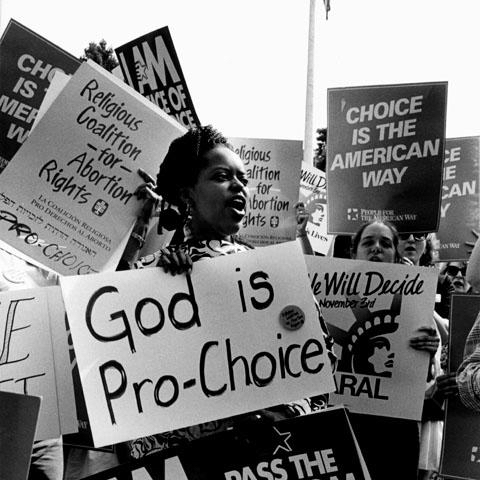

Though quieter than the bullhorns that magnified the hostile chants outside her clinic, Yeo’s faith and her devotion to reproductive rights remained steadfast. She continued to work with other religious leaders and laity to defend Roe and to protect clinics, all the while emphasizing that reproductive freedom is religious freedom. In that spirit, she collaborated with the Wisconsin Council of Churches and the Wisconsin chapter of the National Religious Coalition for Abortion Rights, which had formed to safeguard “the legal option of abortion” and ensure “the right of individuals to make decisions in accordance with their consciences.” She also served on NARAL’s Board of Directors, eventually becoming chair of its board. Locally, she continued to speak about reproductive rights in churches and at synagogues, sometimes to friendly audiences, and sometimes in debate with religious leaders opposed to abortion.

Protesters continued to target MWHO, their actions becoming ever more aggressive. Two violent incidents in May of 1986 permanently scarred Reverend Yeo and her family. In early May of that year, anti-abortion protesters attempted to invade her clinic again. This time, one of the protesters punched Yeo and caused a minor injury. That same month, a protester attacked Reverend Elinor Yeo and her husband. The protester knocked Yeo into the street and pushed Reverend Richard Yeo to the ground, badly breaking his arm. His injury was so severe that he had to be hospitalized and have a permanent steel plate installed. Reports at the time stated that anti-abortion demonstrators rooted for the attack. In the wake of the violence, Reverend Yeo recalled feeling “very fearful for our patients and staff.”

Local mainline Protestant pastors rallied around the Yeos and even met with the Archbishop of Milwaukee, Remberg G. Weakland, demanding that he denounce the protesters and deescalate the violence. The Archbishop, though opposed to abortion, condemned the violence of anti-abortion activists. He published a statement in the Catholic Herald, the official organ of the Milwaukee Archdiocese, instructing that, “In defending the importance of life, we cannot run the risk of making it look cheap by gestures that are offensive or violent to the lives of others.” The Yeos appreciated the Archbishop’s efforts but noted that he had limited control over Catholic anti-abortion activists and less influence over a movement that was increasingly radical and Evangelical. For even as Archbishop Weakland called for nonviolent protest, Evangelical ministers in Wisconsin, like Jerry Horn, openly declared: “If you live by the sword, you die by the sword. What we’re saying is the abortionists are simply getting a taste of their own medicine… What we are seeing is a counter-offensive against the slaughter of unborn children. I think it has catapulted into a holy war over abortion-on-demand.”

The Yeos left Milwaukee in 1987, a year after that clinic invasion. Reverend Richard Yeo received a job offer that Elinor described as “too great an opportunity to miss” and she longed to be closer to her three sons, who had moved back east. At that point, Elinor had directed an abortion clinic for 12 years and by her own estimate, had counseled approximately 30,000 women. When I spoke with her years later, she explained the move in this way:

“It was a hard decision, but I’ll never forget the feeling of relief when we came to Boston and we were living at Charles River Park, which is an apartment complex. They had a concierge at the front desk, and I just remember going up to the twelfth floor where our apartment was, and I felt safe for the first time in I don’t know how long… I don’t think it was a coincidence that two years after we moved to Boston, I had a heart attack. You can just take so much of this nonsense, when it really gets to you.”

Until her retirement, Reverend Yeo worked as director of social work and public policy with the City Mission Society, a United Church of Christ-founded organization that had been pioneering social justice causes in New England since 1816. She continued to worship at the historic Old South Church in Boston.

***

For decades, it has been easier to see how abortion clinics have been besieged by religious forces. Less visible are the ways faith has fortified clinics. Reverend Elinor Lockwood Yeo was born on Valentine’s Day in 1934. She passed away on January 10, 2023 at the age of 88 after her heart failed. For decades, she made reproductive healthcare accessible to Milwaukee women. Her story speaks to a broader pattern of religious life that saw faith leaders—whether in Iowa, Florida, Massachusetts, New York, Rhode Island, Texas and so on—pioneer reproductive healthcare services in order to serve those who wanted nothing more than the ability to control their bodies and their futures.

Reflecting on her life’s work helping women access reproductive healthcare, Reverend Yeo told me the following: “I really believe that women can be moral agents… I always thought that it was our job, among other things, to give our patients hope…that they didn’t have to go through this again…that they were still good people. That they were not criminals, or monsters, or whatever, that they were still good people. I might not have said this to them but I always believed that God still loved them, that their lives were in the hands of a loving God, not a punishing one.” In 2022, she co-authored a statement on “fighting for abortion access” to her congregation: “Each of us needs to find large or small ways through political campaigns and action groups to be more involved in protecting the right to privacy. In this way, we affirm by our actions the strong and inclusive message of our faith.”

Gillian Frank is a historian of religion and sexuality who co-hosts the podcast Sexing History. His book, Making Choice Sacred: Liberal Religion and the Struggle for Abortion Before Roe, is forthcoming with University of North Carolina Press.