More than Missionary

The Cost of Reproductive Freedom

The religious groups that help pay for abortions and the challenges they face

(Image source: Public Good News)

“We need to be concerned,” Reverend Howard Moody wrote in 1972, “with the economic structures that keep people poor as well as the medical system that makes ‘legal’ abortions outrageously expensive.” An early champion of abortion rights, Reverend Moody lamented that freedom of reproductive choice in America came with a hefty price tag. More than half-a-century later, economic scarcity still shackles abortion seekers. Indeed, the story of the ongoing war on abortion access is not just about challenging the legality of abortion. The story is also one of groups attempting to cut off Americans from financial resources that might help them access reproductive healthcare.

The efforts to make abortion expensive were well underway before Roe v Wade and only escalated in 1976 with the passage of the Hyde Amendment, which prohibited the use of public funds for “health benefits coverage that includes abortion.” Subsequent legislation targeted private insurers so that coverage for abortion ranges from non-existent to full coverage (minus deductibles and fees), depending on the state where the abortion takes place. A series of lawsuits have attacked private and public abortion funds that help women pay for abortions. The intent has been to intimidate abortion fund providers and to make the cost of reproductive freedom prohibitively expensive for most Americans. The effect has been to drive greater numbers of abortion seekers into medical debt.

Seen from a different angle, struggles for reproductive freedom have taken place against the backdrop of a for-profit healthcare system and sustained efforts to limit the number of abortion providers and to make their services unaffordable. What may come as a surprise to many is that since the 1960s, religious leaders and institutions have been part of this story of seeking and failing to ensure that the least among us have had the financial means to choose how to manage their pregnancies.

Stories of women scraping together funds abound from the pre-Roe era where access to abortion was prohibitively expensive for most Americans. Women would regularly beg for and borrow money to fund their abortions. Sometimes, groups of friends would pool resources together to help each other. Marion’s story was typical of this. In the fall of 1971, she was an 18-year-old freshman at the University of Florida and discovered she was pregnant. Despite abortion’s illegality in Florida, she was determined to terminate her pregnancy in New York where it was newly legal. The cost of an abortion in New York City was $150 at a clergy-affiliated clinic. The cost of a plane ticket was another $150. And that $300 ($2,400 in today’s dollars) was far beyond Marion’s means.

But Marion was determined. “I organized my girlfriends,” she remembered and “[we] went out to the college quad. And …I’d approach people, and say, ‘I’m pregnant, and I don’t want to be. I’ve got to get to New York to get an abortion. It should be legal. Will you…give me money to, so I can get up there?’” Her friends likewise approached other University of Florida students, told them about Marion’s situation, held out empty coffee cans, and asked for them to donate money. Soon, the coffee cans were filled. “And we raised the hundred and fifty dollars it cost for the abortion, and the hundred and fifty dollars it cost to fly up there, in three days,” Marion explained.

Such hardship cases haunted mainline Protestant and Jewish clergy who regularly helped women find abortion services. “We talk about ways to beg, borrow, and raise money,” Reverend Ross Nicholson reflected in 1971 about his role as an abortion counselor in Michigan. “When these ways are exhausted we sit and cry together in despair.” “After a while,” Reverend Nicholson lamented, “she goes away in silence.” In response, groups like the Clergy Consultation Service on Abortion, individual clergy, and even the Presbyterian Church USA, helped pay for the abortions and travel costs for women who couldn’t afford either.

In many cases, individual clergy would use their own discretionary funds to help women make these trips. Clergy from across the United States recalled that congregants contributed money to help poor women pay for abortions and abortion travel. Reverend Ralph Mero, a Unitarian Universalist, with a congregation outside of Seattle recalled:

“There was money to be used for people in distress, and it might be a winter coat for a kid, or a tank of fuel oil for a family in the wintertime, or emergency food. I interpreted my purview pretty liberally, and helped pay for an abortion. Most of the women were married. They were in their 20s or 30s. Typically, they already had a couple of kids.”

In Philadelphia, Rabbi Harvey Goldman remembered that, “We were finding ways of sending women to England [where abortion was legalized in 1968]… I had some very nice, well-to-do congregants in my congregation…who felt as I did; and, if a woman did not have the means to get over to England, we would find a way, financially, to get her over.” For Goldman, raising these funds for abortion access, “was an issue of human rights. It was an issue of women’s rights, and the fact that the woman owns her own body.” These forms of assistance were vital to individual women and made small dents in a system structured to choke off access to abortion information and resources.

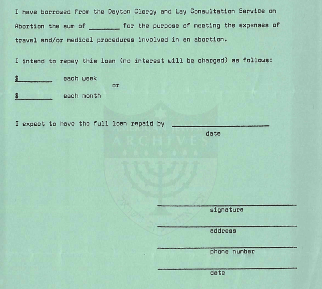

As individual clergy marshaled private funds to make abortion access possible for individual women, branches of the Clergy Consultation Service on Abortion in places like Illinois, Ohio, Nebraska, South Carolina, and Upstate New York, sought to organize their own loan programs that would allow women to borrow money, interest free, to pay for their abortions.

(Image provided by author)

These small efforts dovetailed with larger scale programs administered by the Presbyterian Church USA. In 1970, a prominent businessman and Ruling Elder in the Presbyterian Church gave $50,000 to its Board of National Ministries, in order to create a fund for abortion seekers. By 1971, this program, administered by the Committee on Therapeutic Abortion (COTA), had an operating budget of nearly $100,000. Through COTA, clergy across the South and Southwestern United States offered loans “to the hard-core poor/indigent, e.g. persons on public welfare with very limited income and financial/other resources” so that they could pay for abortions and abortion travel.

But the same program placed clergy from these states in the difficult position of having to pursue recipients for repayment. “We do not wish to pressure anyone,” wrote a loan administrator apologetically in 1971, “nor do we wish to be conned out of money.” The issue, he noted, was that “if loans are not repaid… other women will be denied this opportunity of help.” Still, one can imagine the pressure impoverished loan recipients felt with clergy asking for repayment. Many were barely surviving on paychecks from low paying jobs or miserly welfare funds. The unpleasantness chasing down money from those with very little bleeds through the correspondence from clergy to loan administrators. “I have checked with [name redacted] and get the routine promise that she’ll begin forwarding her $10 per week payments,” wrote Reverend H. Alan Elmore of South Carolina to the Coordinator-Treasurer of the Presbyterian loan program. “She has now obtained a job and is no longer on welfare, so she should be able to do this. I will stay on top of it as well as I can, but I can’t promise that the money will come rolling.”

Even as the prices of abortion dropped across the United States because of the efforts of advocates, demand for financial support continued from abortion seekers. Private efforts could not meet the needs of abortion seekers. “We shall be operating with less than one-half as much money and may expect four times as many requests,” projected administrators of the Presbyterian-run abortion loan program at the end of 1971. The story was no different in the Midwest and the Northeast where clergy reported that one third to one half of their clients were experiencing financial hardship or were indigent.

“It was hard not to become aware as the years passed,” recalled Arlene Carmen, who oversaw much of the national operations for the Clergy Consultations Service on Abortion in the 1960s and 1970s, that, “we were seeing thousands of women all with the same problem, all going through the same struggle, all having some difficulty, or most of them… many of them having difficulty raising the money.”

Nearly six decades after religious pioneers in the abortion rights movement marshaled funds to help abortion seekers, religious groups continue to fund abortions and still struggle to do so. The Red Tent Fund, The Jubilee Fund in Ohio, the Faith Roots Abortion Fund in New Mexico and The Fountain Street Church Choice Fund in Michigan are among the organizations carrying on this work. Part of a constellation of private abortion funds, they are struggling to do so as donations diminish and anti-abortion forces are further cutting public funds. The Supreme Court has enabled states to block Medicaid payments to Planned Parenthood, which has long been one of the largest abortion providers in the United States. State governments in places like Texas, meanwhile, are prohibiting municipal governments from administering their own abortion funds. These endeavors to make abortion criminal and costly are meant to overwhelm one’s pocketbook and one’s spirit.

Across the decades, women have been punished financially with unwanted pregnancies and with the costs of managing them. The community efforts by religious advocates to remediate these punishing costs, worthwhile and noble, have been and continue to be essential acts of triage. At a moment when a right to abortion is precarious at best, and economic pathways to financial support are increasingly tenuous, it is hard enough for community organizations to do more than maintain an impoverished status quo. And those efforts are already monumental. It is all the more essential then, to hang on to the fundamentally moral vision of a world in which universal reproductive healthcare is guaranteed to all.

Gillian Frank is an Assistant Professor in the History of the Modern United States at Trinity College Dublin. His book, A Sacred Choice: Liberal Religion and the Struggle for Abortion Before Roe v Wade, is forthcoming with University of North Carolina Press.