Not So Sorry

The Colonizing Catholic Church, Indigenous Americans, and Problems with Forgiveness

The church contributed to the abuse and death of countless Indigenous peoples. Could refusing the church's request for forgiveness prevent future abuse?

(Image source: Getty Images)

In recent years, people at the university where I teach in California tried to address the fact that we work on land stolen from indigenous people by appending land acknowledgements to their email signatures. But the Ohlone people who had lived on the land where the university constructed its buildings had already been decimated and scattered. The emails may be sent from Ohlone land, but there are few Ohlone left to claim it.

Land acknowledgements are a kind of apology. But for white people, like sticking a Black Lives Matter sticker on their car, they are another performative gesture at trying to make amends for the sins of our ancestors. Whether your white ancestors arrived in America with the pilgrims or more recently like most white Californians, you have benefited from the conquering of lands that belonged to others. Native American activists have become increasingly vocal about this, and, gradually, white Americans have tried to offer apologies. But do these gestures really mean that Native Americans owe white people forgiveness? And after years of being told to “forgive and forget,” can the genocide of Native American people, or any people conquered by others, really ever be forgiven?

A 2015 study by psychologists on forgiveness found that most people forgive in two ways. The first, decisional forgiveness, is a conscious decision to let go of hurt feelings and move forward “free of the effects those feelings can bring.” The second, emotional forgiveness, involves replacing negative emotions toward someone who has wronged you with positive ones, like compassion or empathy. But while most psychologists argue that forgiving can help a person move past trauma, another study in 2011 found that being forgiving can perpetuate and excuse abusive behavior. The fact of the matter is that while forgiveness should theoretically prevent people from reoffending, in many cases, it actually gives them permission to do so—on both personal and communal levels. Indigenous Americans have suffered because of this.

***

California’s oldest standing buildings are the Missions, which were overseen by an ambitious Spanish Franciscan friar named Junipero Serra. Serra, who arrived in Baja California in the late 1760s, had a singular goal: to convert as many of the seemingly recalcitrant Native Californian people as humanly possible. Considering how many Native people ran away from missionaries, they weren’t so much recalcitrant as terrified. One indigenous family seeking help for their sick infant once brought the baby to Serra, who assumed they wanted it baptized, and then fled when it looked like Serra was about to drown their child.

As Serra slowly made his way up California, building missions as he went, more and more Native Californians converted to Christianity. But once they converted, rather than finding salvation, life often became desperate and unpleasant. Not allowed to leave the missions, they were separated from family members, stripped of their languages, rituals, and cultures, and forced to labor for the church. Disease and hunger were rampant. Missionaries beat, whipped, and treated Native Californians with a condescending, infantilizing attitude.

(Mission Santa Clara in California)

By the time I was born, California’s population had been reshaped many times over. Oakland, where I grew up, had gone from a city of Italian and Irish immigrants in the early 20th century to a city with more than 50% Black population during the Great Migration. Immigrants from Mexico and Central America began to pour into California in the 1970s and 80s alongside people from Asia, Southeast Asia, and Africa. But there were always Native Californians, too. It’s just that, thanks to Serra, not many of them remained.

Our teachers, with a mind toward building a more diverse story of California, took us on field trips to see the Miwok Village at Point Reyes National Seashore alongside tours of missions. But for people who grew up in the 1980s and later, instead of hearing stories praising Serra, we began to hear other stories: of disease and death, of cultures wiped out, of people who had once been rich in land now homeless. We learned that some things are unforgivable.

Among those stories, one has stuck with me for fifty years as an example of what it means to decimate a group of people so utterly that there is no possibility of forgiveness. It has also defined both what it means to commit an unforgivable act, and how that act can have repercussions for generations.

On August 29, 1911, a starving Native man wandered into Oroville, California, where he was sent to the town jail. He was Yahi, a tribe that had been deliberately and violently massacred by white settlers. In the 1840s, there were approximately 400 Yahi living in Northern California. By 1911, there was one.

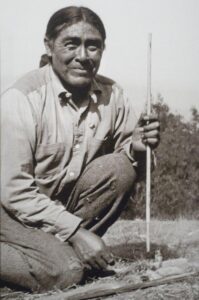

Desperate to get rid of this unwanted man, the town reached out to the University of California Museum of Anthropology, which was at that time located in San Francisco, seeking help for the visitor whose name was unknown. Alfred Kroeber, who ran the museum, proposed that the man be moved into the museum to live rather than repatriated to a reservation in Oklahoma. Because it was a Yahi custom not to speak his name to outsiders, Kroeber began calling him Ishi, meaning “man.” Ishi suffered from numerous health problems in the museum, where he lived for four and a half years. In one of the first photographs taken of Ishi, he is thin, covered in what looks like a loaned coat, and barefoot. The anthropologist James Clifford writes that this image, widely circulated when Ishi was “discovered,” was the beginning of Ishi’s story being stolen from him. “Stripped of any context, he is pure artifact, available for collection; pure victim, ready to be rescued.”

Kroeber considered Ishi a friend, and he and other UC anthropologists tried to learn Ishi’s language and customs, hoping to preserve them. But their methodology was, by today’s standards, dehumanizing. Ishi was advertised as “the last wild Indian in California,” and essentially put on display in the museum, where he would carve obsidian arrowheads and sing Yahi songs for crowds of tourists. Against his will, Ishi traveled with Kroeber to the site where his family was massacred to help Kroeber document Yahi life. Ishi’s narrative became Kroeber’s narrative, and Kroeber’s growing fame became dependent on Ishi.

(A photo of Ishi. Source: California Museum)

Ishi struggled in the museum, partly because he was surrounded by the remains of other Native Californians, and partly because he was not accustomed to living indoors or wearing Western clothing. He would sometimes be sighted hunting on nearby Mount Parnassus, but for the most part, he was confined indoors and forced to be a living exhibit. By many accounts, he was friendly, but one can only imagine what he went through psychologically spending nights surrounded by the bones of massacred relatives.

When tuberculosis swept through San Francisco in 1916, Ishi contracted it, probably from a curious museum visitor eager to see a live “wild Indian.” When he died, Kroeber initially opposed letting Ishi’s body be autopsied, but later agreed to have Ishi’s brain sent to the Smithsonian, where it remained until 2020.

By then, narratives about Ishi’s life had changed. Kroeber’s wife Theodora, also an anthropologist who studied Native Americans, wrote what was for many years considered the definitive book about Ishi’s life, Ishi in Two Worlds. But it was an imperfect book in many ways.

As a child, like many Californians, I was assigned a young reader’s version of Theodora Kroeber’s book in school, so the Ishi I knew was the Kroeber’s Ishi, not the Ishi who belongs to the Native Californians who would later spend decades fighting to reclaim his brain so they could lay it to rest with his ashes. Among the mythological stories the Kroebers created is that Ishi was the “last” Indian living wild in California, which is clearly not true: while Ishi’s tribe was wiped out, the descendants of many of the Indians who ran from Serra still live there today.

Even while it acknowledged the genocide of Native Americans and grappled with the trauma Ishi experienced when his family was massacred, Theodora Kroeber’s book also contributed to the mythology of the “healed” Native American. She created a narrative of a person who has been tortured but still manages to be able to move past pain and into forgiveness. Kroeber divides her book into two sections, “The Terror” for Ishi’s life before he arrived at the museum, and “The Healing” once he got there.

But the truth is much more complicated. Ishi will never be able to tell us if he forgave the people who slaughtered his family, if he forgave the seemingly well-meaning white anthropologists who placed him in a museum and exploited his story, or if he forgave Serra and gold prospectors and everyone else who has tried to reinvent California in their own image. Ishi will not even be able to tell us his real name, because it could only be spoken by another Yahi, and they are gone. The remains of Native people that so bothered Ishi when he lived at the Museum of Anthropology were moved along with the rest of the museum to the UC Berkeley campus soon after Ishi died. Thousands of students, faculty, and staff sit in classrooms and offices built over containers of those remains.

In 2015, despite protests from Native Americans, Pope Francis canonized Junipero Serra in Washington, D.C. The pope described Serra as “excited” to learn Native customs and ways of life. But Native Americans disagreed. Five years later, as statues of Confederate generals, Christopher Columbus, and other disgraced historical figures were being toppled across the country in the wake of the Black Lives Matter movement, Native activists knocked down a thirty-foot-tall statue of Serra in San Francisco’s Golden Gate Park. Statues of Serra soon fell in Sacramento and Los Angeles as well. California governor Gavin Newsom had delivered a formal apology to California Native people in 2019, recognizing the history of genocide in the state. But for Native activist Morning Star Gali, “an apology is nothing without action,” and for her and other California Native people, statues of Serra were a reminder of a painful past and needed to go.

(Statue of Serra. Image source: Jaime Reina for Getty Images)

The Catholic Church disagreed. San Francisco archbishop Salvatore Cordileone did not apologize to Native activists for the damage the church had done to them throughout history. Instead, he called the activists a “mob,” accused them of “an act of sacrilege,” and called toppling the statue blasphemy. Cordileone performed an exorcism at the site of the statue, with his own film crew on hand, documenting the ceremony on YouTube, saying “evil has been done here” and calling Serra a hero. The statue, depicting Serra thrusting a cross forward with his arms spread wide, now dented and splattered with red paint, has been put in storage. The California legislature voted to replace it with a statue honoring Native Californians. To this day, such a statue does not exist.

***

In July of 2022, Pope Francis made what the Vatican described as a “penitential pilgrimage” to Canada. The history of Canadian residential schools became an international scandal as reports went public of thousands of unmarked graves of First Nations people on the sites of former schools. Led by missionaries from Catholic and Protestant denominations on the premise that they would educate First Nations children, Canadian residential schools instead performed what many Native people consider cultural genocide.

Effectively stealing, in most cases, First Nations children from their parents, missionaries who ran residential schools sexually, physically, and psychologically abused generations of Native Canadian children. And they learned how to do this from their American neighbors. Nicholas Flood Davin, a Canadian politician sent to the U.S. to study “industrial schools” for Native Americans, wrote in 1897 that “if anything is to be done with the Indian, we must catch him young.” To achieve the “aggressive civilization” desired by these politicians, missionaries separated siblings in the schools, weakening family ties, and stuck needles into the tongues of children caught speaking their indigenous languages.

First Nations religions, languages, and cultures were annihilated, and untold numbers of children died in residential schools. One report from 1907 estimated a quarter of previously healthy children died in the schools. And anywhere between half and three quarters of those sent to residential schools later died from suicide, addiction, or violence.

Residential schools still existed as recently as 1996, and the first apology for the Canadian government’s part in them occurred in 2008, when Stephen Harper, then the Prime Minister, offered a public apology before an audience of First Nations people. “The Government of Canada,” Harper said, “sincerely apologizes and asks the forgiveness of the Aboriginal peoples of this country for failing them so profoundly.” Loraine Yuzicapi, who had been sent to a residential school in the 1950s and sat in the audience as Harper apologized, had a succinct response to a journalist’s question about Harper’s apology. “It wasn’t good enough,” she said.

(A Canadian residential school. Photo taken in 1940. Image source: Library and Archives Canada)

For people who were colonized or enslaved, as well as for their descendants, our growing understanding of trauma theory backs up what they have long said: apologies are not always enough to earn forgiveness, because violence, whether mental, physical or spiritual, can do damage that lasts generations. Residential schools may have been formed for what their founders saw as a meaningful purpose, the assimilation of indigenous people into white society and the salvation of their souls through forced conversions to Christianity, but anyone with even a cursory knowledge of missionary history is aware that violent white supremacy shaped those missions.

By the time Pope Francis arrived in Canada, First Nations people were understandingly skeptical. Calling the residential schools a “disastrous error” and “catastrophic,” the pope said he humbly begged forgiveness “for the evil committed against the Indigenous peoples.” But the pope also said missionaries were acting on behalf of the government, what he described as the “colonizing mentality.” Pope Francis did not ask forgiveness for the Catholic Church itself, but for its members who abused children. In doing so, the pope perpetuated the same patterns that made the sex abuse crisis possible.

By pointing the finger at individuals rather than the institution that enabled and even encouraged them, churches and governments alike involved in the residential schools have used the same “bad apples” excuse for generations. The problem is that this effectively allows the institution to call itself blameless. And that in turn increases the potential for the same abuses to happen again.

Murray Sinclair, an Ojibwe Canadian senator and the former head of Canada’s Truth and Reconciliation commission, said that this deflection made the pope’s apology feel hollow. According to Sinclair, the pope’s words “left a deep hole in the acknowledgement of the full role of the church in the residential school system, by placing blame on individual members of the church.” For Sinclair and many other First Nations people, the pope’s apology was too little, too late. They would not be granting forgiveness.

***

In his book The Body Keeps the Score, psychiatrist Bessel Van Der Kolk writes that for the traumatized person, “the past is alive in the form of gnawing interior discomfort.” Physical aftereffects of trauma become “visceral warning signs,” and survivors of trauma “become expert at ignoring their gut feelings and in numbing awareness of what is played out inside.” Van Der Kolk’s hypothesis is that this is another form of the fight or flight instinct experienced by people with anxiety and panic disorders. Because they’ve experienced trauma, they never feel safe, and as Van Der Kolk writes, “Being able to feel safe with other people is probably the single most important aspect of mental health.”

Many Americans have looked to Canada as a country with more exemplary social equity, and knowledge of the residential schools shattered that. Since we know America is not a safe country for women, people of color, queer people or, increasingly, children at risk of being shot at school, the question remains whether or not the United States, as a nation that has inflicted trauma on generations of people, is worthy of forgiveness.

In an article in Indian Country magazine, Dina Gilio-Whitaker, a member of the Colville tribe, writes about attending a production of a play by a Native American writer. The play posed the question of whether or not Native Americans can forgive what was done to them by the United States, and at the end of the play, a non-Native audience member turned to Gilio-Whitaker and said “you have to forgive if you want to heal.” Gilio-Witaker, who says that she experienced domestic abuse, writes that granting forgiveness was not what she personally needed to overcome trauma. She needed to get away from the abuser. She adds that being taught that forgiveness was the only way to move past the abuse perpetuates a victim mentality for abuse survivors because they can be stuck in a perpetual experience of trauma while the abuser moves on.

On a collective level, after war or genocide or colonization, communities “face the extremely challenging prospects of having to rebuild,” while also coping with the psychological impact of violence. After a violent conflict, people on both sides have to find a way to exist alongside one another. Instead of asking people stuck together in the aftermath of violence whether they can forgive, Gilio-Whitaker suggests a better question: what will it take to heal historical wounds, and “heal the relationships between indigenous communities and settler governments and societies?” If we can move past an expectation of forgiveness, she writes, the oppressed are no longer “held to an impossible standard,” and we can also recognize that healing is a shared responsibility, and not an individual one.

Perhaps if we can let go of the idea that forgiveness might be possible after something as unfathomable as a genocide or war, or incest, domestic abuse, rape or a million other traumatizing acts, we might also be able to let victims and their descendants experience a sense of freedom since they no longer “owe” anyone. The Rev. Eric Atcheson, an Armenian-American whose ancestors survived the Armenian genocide, told me that he does not see it as his or any other Armenian person’s responsibility to be forgiving, because the people who could have offered forgiveness are now dead.

“If God wants to forgive culprits of a genocide,” he says, “that’s God’s affair. I don’t get to forgive them in my ancestors’ stead.” Rev. Atcheson adds that those who accuse the descendants of genocide or war to be “clinging to the past” by refusing to forgive are incorrect. In refusing to forgive or forget the Armenian genocide, Atcheson believes he is “setting [himself] free while the deniers remain burdened.” In many ways, this makes perfect sense. We are taught that forgiveness is an unburdening and a letting go, but what if realizing you cannot forgive someone or something is the actual unburdening? As Atcheson says, if it is God’s decision whether someone is forgiven, that can free us from the guilt of feeling like we are bad people when we cannot do the same.

And to reduce any group of people to their experience of suffering is also a form of dehumanization. It’s amazing to read that Ishi laughed, told jokes, and enjoyed walking around San Francisco and meeting people considering his entire family was massacred while he hid and watched. That doesn’t necessarily mean he was forgiving, but that like every other human being, he felt a range of emotions that extended beyond trauma and its impact on him. But he also continued to speak Yahi, to practice his tribal rituals, to hunt and carve arrowheads. Living in the museum may have felt like a trap, but when Kroeber wanted to take Ishi back to his home territory, Ishi did not want to go. To return meant returning to the site of the trauma. He was trapped in a liminal space, and that is where he died.

To imagine Ishi or any person who survived a mass slaughter laughing or smiling may tempt us to think they have “let go,” forgiven, or moved on. But anyone who’s been to a funeral knows that sometimes you laugh hard at funerals because this, too, is a release. That’s not the same as moving on or moving past something, but a momentary opportunity to feel something other than anxiety or grief. The person being asked for forgiveness, as Gilio-Whitaker writes, is also being “held to an impossible standard.” That, too, is turning human suffering into caricature, the “noble savage,” or the rape victim so holy she is willing to forgive the man who violated her, or the former slave who somehow forgives the person who owned and abused their body.

If we are called to be forgiving no matter what, many people who have been through hell will fail. Perhaps what needs to be forgiven is, instead, the inability to forgive.

Kaya Oakes is the author of five books, most recently including The Defiant Middle: How Women Claim Life’s In Betweens to Remake the World. She teaches writing at the University of California, Berkeley.