The CIA’s Religious Approach to Espionage

An excerpt from the book Errand into the Wilderness of Mirrors: Religion and the History of the CIA

(CIA headquarters. Photo credit: Larry Downing for Reuters)

The following excerpt comes from Michael Graziano’s book Errand into the Wilderness of Mirrors: Religion and the History of the CIA. (© 2021 by The University of Chicago Press. All rights reserved.) The book explores how the CIA sought to understand religion throughout the world, while often missing the mark in ways that led to disaster. This excerpt from the Introduction explores what the book, borrowing a term from World War II American spies, calls the “religious approach” to intelligence. The religious approach was shorthand for a wide-ranging set of assumptions about what religion was, how it functioned, and how its presumably universal appeal could be used to advance U.S. goals.

***

More than half a century ago, Perry Miller’s Errand into the Wilderness (1956) described the plight of the New England Puritans, strangers on a strange shore, seeking to revive anew the mission to which they were sure their group was called. The Puritans felt a sense of disquiet and unease in a new wilderness as they began to understand themselves as a people apart from the England from which they came. In their own estimation, they had succeeded in their “errand” but, thanks to the English Civil War, no one back home was watching their city on a hill. It was a hollow victory. “There was nobody left at headquarters to whom reports could be sent,” Miller wrote in his book that would come to reshape the study of religion in America for the remainder of the century.

The idea for Miller’s book, according to the author’s preface in Errand, came to him while he stood on the banks of the Congo River. Much has been made of this moment, and its role in shaping American studies and US intellectual history. It is all the more telling, then, that the Congo story was at least partly fabricated. “Yes, there is a kind of truth in Perry’s romantic reference in Errand,” wrote Elizabeth Miller about her husband’s scene, “but Perry, who was a writer, was in part creating, after the fact, an effective anecdote as well as an explanation of why his own errand had been undertaken.” While the Congo story may not have been entirely true, Miller did have opportunities to see and think about the American mind in a global context. Miller worked for the CIA’s predecessor, the Office of Strategic Services (OSS), during World War II in Germany where he specialized in psychological warfare, a domain that frequently applied the knowledge gained through the religious approach. The accuracy of Errand’s account was not nearly as important as how it was delivered and what it achieved. William Donovan, Miller’s boss and the director of the OSS, would have been proud.

The idea for Miller’s book, according to the author’s preface in Errand, came to him while he stood on the banks of the Congo River. Much has been made of this moment, and its role in shaping American studies and US intellectual history. It is all the more telling, then, that the Congo story was at least partly fabricated. “Yes, there is a kind of truth in Perry’s romantic reference in Errand,” wrote Elizabeth Miller about her husband’s scene, “but Perry, who was a writer, was in part creating, after the fact, an effective anecdote as well as an explanation of why his own errand had been undertaken.” While the Congo story may not have been entirely true, Miller did have opportunities to see and think about the American mind in a global context. Miller worked for the CIA’s predecessor, the Office of Strategic Services (OSS), during World War II in Germany where he specialized in psychological warfare, a domain that frequently applied the knowledge gained through the religious approach. The accuracy of Errand’s account was not nearly as important as how it was delivered and what it achieved. William Donovan, Miller’s boss and the director of the OSS, would have been proud.

Hundreds of miles to the south of Miller’s wartime operations, another OSS officer was hard at work in Rome. James Jesus Angleton would develop a reputation within OSS as an expert in counterintelligence—protecting against foreign espionage—in part through his policing of the religious approach’s limits at the Vatican. Like Miller, Angleton was a university man at heart, but unlike Miller—who, according to his OSS file, “wants to return to his position in the Harvard faculty as soon as possible”—Angleton stayed in intelligence work after the war. Angleton eventually became the CIA’s legendary counterintelligence chief. David Atlee Phillips, a career CIA officer, described Angleton as “CIA’s answer to the Delphic Oracle: seldom seen but with an awesome reputation nurtured over the years by word of mouth and intermediaries padding out of his office with pronouncements which we seldom professed to understand fully but accepted on faith anyway.” Both OSS officers, Miller and Angleton were tasked with understanding and manipulating the human mind. It was not easy. Angleton, quoting a verse from T.S. Eliot, described the business of espionage as a “wilderness of mirrors.” While their post-war careers led them to different institutions—the CIA for Angleton, Harvard for Miller—their work was not entirely dissimilar. They were experts at crafting a useful story to influence how others think about America in the world. They were both, in their own ways, masters of American studies.

Success in the war brought about different uncertainties, and the CIA was left alone with the world: a wilderness different in scale rather than kind. Empowered with considerable independence and little oversight, the CIA became the “headquarters” to which reports would be sent. While Miller never worked for the CIA, the strategies the Agency employed—like the religious approach to intelligence—were not all that different from the ones Miller used to understand the Puritans in 1956. Miller and the CIA took ideas seriously. Many of the intelligence officers in this book would likely have agreed with Miller’s confident pronouncement that “the mind of man is the most basic factor in human history.” If one could understand how humans thought, then one could understand how humans worked. Armed with this knowledge, one could influence people toward particular ends. The major question—and errand—of the religious approach to intelligence was to determine how the human mind could be used to shape the future of humanity, radiating from the United States outward into the world.

This confidence in America’s ability to understand and influence the world is at the core of the religious approach to intelligence. It was also sometimes wrapped up with a disregard for the consequences of these efforts to understand. “You have to understand the culture of the clandestine service,” former Director of Central Intelligence Robert Gates explained. “You haven’t been through what they’ve been through. They’ve put their families through hell at times…some may eventually end up in London or Paris. But they start out in Third World hellholes without even a Western doctor when their kids get sick. They have a strong sense that almost no one understands them or what they do. So they feel defensive and misunderstood.”

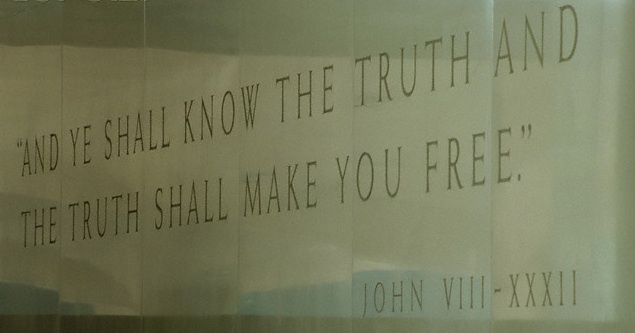

And yet, they felt compelled to understand everyone and everything. To work for the CIA was to be part of an institution that saw knowledge of the world as one way to secure freedom in it. Carved in marble at the CIA’s original headquarters is the Agency’s unofficial motto, from the Gospel of John: “And Ye Shall Know the Truth and the Truth Shall Make You Free.” The authors of the Gospel of John saw Jesus as the divine logos, revealing the divine order of the universe for all to see. The CIA had an errand in this new, postwar wilderness, bringing truth and freedom to other peoples beyond the borders of nation or religion. The Agency’s own accounting of the word made flesh sits across the lobby: 137 stars that make up the Memorial Wall, one for each CIA officer killed in the line of duty. This is one measure of the human costs of these efforts, but it is not the only one. As this book shows, the reality of intelligence operations was far more complicated, with profoundly troubling consequences for people around the globe.

(From the CIA’s original headquarters: A quote from from the Gospel of John carved into marble)

This book begins with the CIA’s predecessor, the OSS, and its influential wartime leader, William Donovan. Under Donovan, the intelligence agency became a unique place to study religion, combining considerable financial resources, spotty oversight, and a desire to know everything about everywhere. William Casey, who got his start in Donovan’s OSS and went on to lead the CIA under President Reagan, explained that “Donovan’s grasp of this elusive, multiple yet crucial nature of intelligence led to the CIA…becoming not merely a spy outfit but one of the world’s great centers of learning and scholarship and having more PhDs and advanced scientific degrees than you’re likely to find anywhere else.” Those who served with Donovan viewed him as the demiurge of American spy craft, imbuing the OSS with the certainty that the world could be understood and manipulated according to American aims. “We can know,” OSS officer Stanley Lovell explained, “Iron curtains and Bamboo curtains are only impenetrable to those who will not open their eyes.” This story begins by charting the efforts of American intelligence officers, alone in a new wilderness, as they learned to see.

Michael Graziano is assistant professor of religion at University of Northern Iowa.

***

Interested in more on this topic? Check out our fascinating conversation with Michael Graziano in episode 19 of the Revealer podcast: Religion and the CIA.