Political Feelings

Suffer the Children

Why the charge of child sacrifice thrives in our contemporary discourse.

The Fall of the Titans by Cornelius van Haarlem in (1588–1590)

In 310 BCE, Agathocles, the tyrant of Syracuse, invaded North Africa. Burning his ships behind him, Agathocles and his army marched along the coast to Carthage, where they set up for a long siege.

According to the Greek historian Diodorus Siculus (who wrote two and half centuries later), when the Phoenicians within Carthage saw the Sicilian Greeks encircling them, they took it as a sign of divine punishment, and sought to make religious amends.

Offerings were sent to Tyre, the city whence the Carthaginians had come as colonists, and sacrifices were made to its pantheon. But when these produced little result, the Carthaginians decided the arrival of their enemies was actually chastisement from one of their own gods, one of the oldest, whose cult they had of late been neglecting. Diodorus Siculus calls this god ‘Cronus’ — seeing him apparently as a kind of avatar of the god the Greek’s worshipped as the father of Zeus — but the Semitic-speaking Phoenicians themselves doubtless called him something else.

In any event, in the eyes of the Phoenicians, “Cronus had turned against them inasmuch as in former times they had been accustomed to sacrifice to this god the noblest of their sons, but more recently, secretly buying and nurturing children, they had sent these to the sacrifice; and when an investigation was made, some of those who had been sacrificed were discovered to have been supposititious.” Cronus, in other words, demanded the sacrifice of children of noble blood; certain impious Carthaginian shirkers, however, had been passing off slave children as sacrifices instead. Two hundred noble children were thus seized and sacrificed; another three hundred supposedly volunteered and were killed as well. In Diodorus Siculus’ telling, the sacrifices were public, and performed in a striking fashion. “There was in their city a bronze image of Cronus, extending its hands, palms up and sloping towards the ground, so that each of the children when placed thereon rolled down and fell into a sort of gaping pit filled with fire.”

The very idea of mass child sacrifice is appalling, and this particular image of the practice has, understandably, proven remarkably durable. The question of whether and to what extent Phoenician religious practice actually involved such child sacrifices, meanwhile, has long been an object of debate.

Like Agathocles — who lost two of his own sons in the process — other Greek and Roman figures regularly waged war on Carthage; the numerous references to Phoenician child sacrifice among classical Greek and Roman authors must thus be viewed with some skepticism, even as possible propaganda.

So too with other sources. The Phoenicians were a cosmopolitan people, with entrepots around the Mediterranean, and as the Canaanites they play a role in the Hebrew Bible. The Tanakh condemns them for sacrificing their children to Moloch (likely the god whom Diodorus Siculus mistook as Cronus), and repeatedly forbids the practice among Israelites. In Deuteronomy and Leviticus, the rejection of child sacrifice is presented as fundamental to Israelite self-definition, bound up (as the binding of Isaac in Genesis 22 illustrates) in its divine covenant and territorial patrimony. As with Greek and Latin sources, a modern skeptic can thus be suspicious of ancient propaganda — or at least exaggeration — in Biblical descriptions of child sacrifice as well.

Debates rage among archaeologists too, with furor centering around the interpretation of abundant child remains found at special cemeteries known as tophets (a term with roots in the Biblical description of the practice, and often deployed as a synonym for “hell”). Some researchers have insisted that these remains are of miscarriages or children who had died from illness; more recent analysis suggests that they were indeed ritually sacrificed, in bids for divine favor or to fulfill past vows.

The Sacrifice of Isaac by Caravaggio (1590-1610)

No matter the latest findings or interpretations, the debates over bones and texts will likely rage on endlessly. Which in itself demonstrates the potent horror of the image of child sacrifice: it is an explosive thing to conjure, an ultimate image of depravity one can invoke. It defines and condemns the cultures and beliefs with which it is associated as backward, perverse, and barbaric. The image of child sacrifice correlatively functions to support narratives of how some superior societies supposedly have progress away from ancient depravity. By the same token, it also taps images of the most horrifying and comparative recent episodes of genocide and political violence. Thus, for example, Elie Wiesel, not long before his death, in a full-page open letter that appeared in numerous American and British newspapers in 2014, wrote in defense of IDF operations in Gaza: “In my own lifetime, I have seen Jewish children thrown into the fire. And now I have seen Muslim children used as human shields, in both cases, by worshippers of death cults indistinguishable from that of the Molochites.”

Scholars like Seth Sanders (writing in Religion Dispatches) have elegantly addressed Wiesel’s claim in both its theological and political context. The brilliant satirist Eli Valley has skewered its moral politics as well. For our purposes, what matters here is the simple fact of Wiesel’s making the argument in the first place, its immediate legibility in terms of the moral outrage it brings to bear on those it condemns, and the justification it correlatively furnishes on those it vindicates. After the immediate revulsion, the shock, that, These People kill their own children — the takeaway is simple. No matter the ultimate body count, or the technical question of whose weapons or tactical decisions do the actual killing, any group that could be said to willingly sacrifice its young must, like Carthage, be destroyed. They are an abomination; they must not be suffered to exist.

In this mode — as a synecdoche for depravity-that-must-be-stamped-out — the charge of child sacrifice thrives, with varying degrees of subtlety and transformation, in our contemporary discourse. First and foremost, the Blood Libel specifically — that longstanding Western tradition of accusing Jews of secret ritual killing of Christian babies — persists to this day, whether voiced as such by unreconstructed anti-Semites, or packaged, suitably tweaked and memefied, by alt-right activists and celebrities. This hoary conspiracy theory coexists with, and bleeds into, other narratives about elite corruption, a lexicon in which horrific violence against children regularly functions as a kind of Ultimate Horror and Primal Sin — the symbol and material correlative of unspeakable transgression, Satanic pacts, and The Evil That Goes On Behind Closed Doors.

From tales of Democratic National Committee members supposedly torturing children beneath Comet Ping Pong Pizza in Washington to the feverish predictions QAnon, the American right has proven a particularly welcome market for such thinking. Meanwhile, anti-abortion rhetoric painting Democrats as the party of “infanticide” has been renewed across the Republican mainstream.

In some instances, a fixation with child-murdering Death Cults can seem not just a primary feature of right-wing political expression, but its sole preoccupation, a frame for understanding everything else. Thus, for example, both the Green New Deal and pro-choice stances of politicians like Alexandra Ocasio-Cortez can be exposed, one columnist at (erstwhile Tea Party clearing house) TownHall.Com argues, as expressing a single underlying evil: “When Democrats argue that abortion should be used as a means to improve modern weather, they are no different than the Aztecs, Mayans, and Incas who called for the sacrifice of young children to improve the climate. Both have the same unrealistic intent — change bad weather; and, both have no comprehension of the brutality of murder and maiming of human children.”

What is less remarkable than the fact that such polemics about child sacrifice should continue to exist (how could they not, since they’re at least as old and as ingrained in Western culture as the Bible?) is that, in a truly gobsmacking way, they are entirely gratuitous compared with the actual, unvarnished truth.

One need not confabulate tales of cabals of authority figures secretly engaged in outlandish and heinous abuse; one need simply read the headlines. Consider the latest developments in the case of Jeffrey Epstein, a story which might strike those previously unaware of it as too grandiosely horrifying to be real, like a hideous mashup of the Marquis de Sade and feverish 4Chan speculation, playing out in the highest corridors of American power. Yet as documented in a devastating series in The Miami Herald, it is all too real. A hedge-fund manager worth $2 billion, Jeffrey Epstein is a convicted sex offender whom investigators — including the FBI — credibly contend has assaulted and/or raped hundreds of middle and high school age girls over the course of decades. A prominent socialite and political donor, Epstein apparently did all this while rubbing shoulders with friends including Bill Clinton, Donald Trump, Alan Dershowitz, the Duke of York, Kevin Spacey and other famous names, many of whom variously vacationed or travelled with Epstein on the jet he used to circulate between residences in Florida, New York, New Mexico, and a private island.

Through the efforts of a top-notch legal team (including both Dershowitz and Ken Starr), Epstein managed to avoid state charges for child prostitution. He even apparently helped draft his own federal indictment, securing a plea deal that immunized him and multiple accomplices from federal charges and resulted in a minimal sentence whereby he was allowed to spend up to twelve hours a day, six days a week, in his Malibu office, receiving visitors including young women. Now a free man, he continues to jet-set more or less at will.

Epstein’s deal was brokered by then-US Attorney for the Southern District of Florida, Alexander Acosta, who lied to Epstein’s victims about the deal’s existence while concluding it. Acosta is currently serving in Donald Trump’s cabinet as Secretary of Labor. He continues to hold this position despite the ruling of a Federal judge that Epstein’s deal broke the law.

Meanwhile, some of Epstein’s victims have alleged that he gave them to friends to abuse as well. “And then a pat on the back, You’ve done a really good job, thank you very much and here’s $200 dollars,” one victim, Virginia Roberts, told the Herald. “And before you know it I’m being lent out to politicians and to academics, to people that — to royalty! — people that you’d never think, like, How did you get into that position of power in the first place if you’re this disgusting, evil, decrepit person on the inside?”

Saturn Devouring His Son by Francisco Goya

There’s a reflexive temptation to take Virginia Roberts’ rhetorical question literally, and answer, That’s exactly how and why they get and keep their power to begin with. But this temptation is actually a bid to hide behind cynicism. Because Roberts, more than anyone, knows what’s she talking about. The full of force of her question lies in that she knows precisely how cruel and perverse abusive elites can be and she is still and even more shocked by the gap between their mainstream public respectability and their personal evil. Part of what shocks her, in other words, is not just the depravity of the powerful, or how much impunity wealth and influence can buy, but the way in which collective memory and public institutions seem incapable of integrating elite depravity and impunity into long-term consciousness or serious action.

Even for those with no reason to be shocked by anything, the dissonance still stupefies.

In June 2016, a California woman filed a lawsuit alleging that, in 1994, when she was 13 years old, Donald Trump raped her at a party at Jeffrey Epstein’s mansion in Manhattan. Trump and Epstein are longtime associates. “I’ve known Jeff for fifteen years,” Trump told New York Magazine in 2002. “Terrific guy. He’s a lot of fun to be with. It is even said that he likes beautiful women as much as I do, and many of them are on the younger side. No doubt about it — Jeffrey enjoys his social life.” The woman remained nameless, but announced she was coming forward for a press conference on November 2, the day before the election. She then cancelled her appearance and withdrew her lawsuit, citing threats to her life. Trump (and Epstein) have denied her story.

Some twenty women have accused President Trump of sexual misconduct. Several women who participated in a Miss Teen USA pageant Trump owned have also told stories of his walking in to inspect them as they changed in their dressing rooms backstage. “Don’t worry, ladies,” one recalled him saying during an episode in 1997, three years after the alleged child rape at Epstein’s, “I’ve seen it all before.” The girls present in this episode included one as young as fifteen.

The dissonance is stupefying. There is no need for tinfoil-hat messageboard speculation or Lovecraftian True-Detective-style secret conspiracies. The exploitation and abuse of minors is right there, as cruel and ghoulish as you could imagine, out in the open. They are everywhere, overwhelming. Any given allegation will be debated endlessly and then forgotten, such that, while all of them may seem entirely plausible, no single one ever seems to rise to the level of being the one that will push opinion (or prosecution) over the edge. No one story seems like it can ever make a difference, precisely because there are so many of them. Meanwhile, institutional inertia and blatant corruption continue to insulate the powerful from serious accountability. In other words, the very scale, horror, and obviousness of the abuse is so great, and the accountability so obviously lacking, that a profusion of allegations paradoxically inoculates the accused through sheer repetition.

Trump is not alone in enjoying this dynamic. Other individuals and institutions enjoy — and weaponize it — too. Speaking before an episcopal conference this February, Pope Francis spoke in broad terms of “the scourge of the sexual abuse of minors.” Drawing heated criticism from victims’ advocates, Francis resolutely spoke of sexual abuse in remarkably broad terms.

Finally pivoting to the question of abuse in the Church twelve paragraphs in, Pope Francis stated: “We are thus facing a universal problem, tragically present almost everywhere and affecting everyone. Yet we need to be clear, that while gravely affecting our societies as a whole, this evil is in no way less monstrous when it takes place within the Church.”

Diluting any specificity of clerical sexual abuse into the strange question of who might want to see abuse as less monstrous when it occurs within the Church, Francis gestured at the relation between power and abuse before promptly eliding any consideration of sexual abuse in the context of power dynamics within the Church in favor of talking about “abuse” writ large:

It is difficult to grasp the phenomenon of the sexual abuse of minors without considering power, since it is always the result of an abuse of power, an exploitation of the inferiority and vulnerability of the abused, which makes possible the manipulation of their conscience and of their psychological and physical weakness. The abuse of power is likewise present in the other forms of abuse affecting almost 85,000,000 children, forgotten by everyone: child soldiers, child prostitutes, starving children, children kidnapped and often victimized by the horrid commerce of human organs or enslaved, child victims of war, refugee children, aborted children and so many others.

Francis thus presented sexual abuse in terms of a kind of both transhistorical universality and eternal evil.

[This] is, and historically has been, a widespread phenomenon in all cultures and societies. Only in relatively recent times has it become the subject of systematic research, thanks to changes in public opinion regarding a problem that was previously considered taboo; everyone knew of its presence yet no one spoke of it. I am reminded too of the cruel religious practice, once widespread in certain cultures, of sacrificing human beings – frequently children – in pagan rites. … Before all this cruelty, all this idolatrous sacrifice of children to the god of power, money, pride and arrogance, empirical explanations alone are not sufficient….So what would be the existential “meaning” of this criminal phenomenon? In the light of its human breadth and depth, it is none other than the present-day manifestation of the spirit of evil. If we fail to take account of this dimension, we will remain far from the truth and lack real solutions.

Moloch reemerges here, as does the idea of atavistic, demonic evil, operating across human history through secrecy and depravity, surrounded by taboos. Yet, truth be told, there seems to have been little “taboo” about what the worshippers of Moloch did. They left frank inscriptions about what they did and why, the deals they hoped to secure, the promises they killed to fulfill. They may not have had a bronze statue of Cronus, but the sacrifices were public enough, not hidden. Indeed, as some interpreters have suggested, this public awareness may have been the whole point. Phoenician practices of child sacrifice, they suggest, functioned as a mechanism for ensuring social cohesion. Since each elite family would have to make a sacrifice, and thus be equally bound in the enterprise of state. The problem, as Diodorus Siculus himself hints, arose when some Carthaginians weren’t sacrificing their own kids, but disposable substitute ones, the kids of others, who came cheap. In other words, they committed the impiety not of duping the gods, but their own elite confederates. Certain pacts must be kept above all.

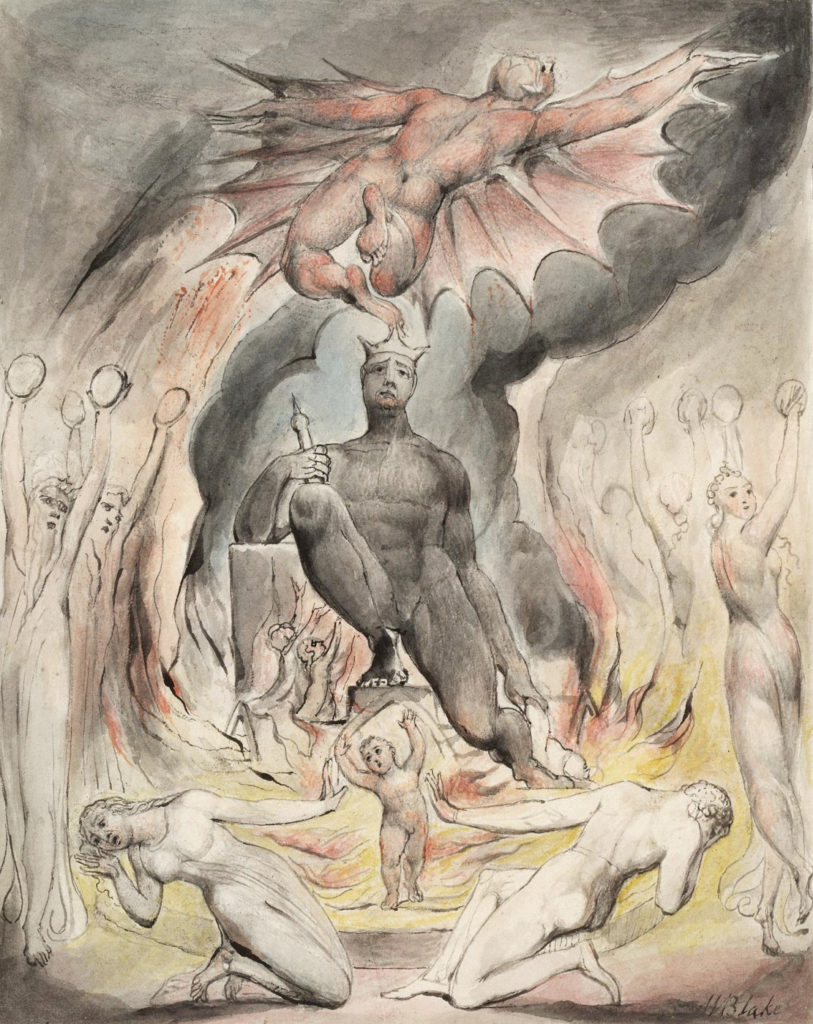

The Flight of Moloch by William Blake (1809)

Today, what is perhaps more amazing than the ubiquity of revelations of abuse around us that they are frequently not even revelations at all. From the Church to Trump to Epstein to Michael Jackson to R. Kelly, the stories seem to have been going on forever, and even the newest allegations are marked with a kind of already-anticipated, horrifying familiarity. Vindication, if any is to come, seems like it will only ever arrive too little, too late, in a different kind of fuzzy temporality altogether.

After so much impunity, horror behind closed doors can be easier to imagine, and to be seen as inevitable, than public justice. Which is all to say that, at least as far as the immiseration and abuse of children is concerned, the idea of “revelation” has lost its apocalyptic charge. Everything is shown – but what is revealed entails no prompt consequences, let alone justice. Meanwhile, written even more prominently than tales of abuse and conspiracies of exploitation, signs of another kind of apocalypse proceed apace. The climate assessments are clear. Even if we undertake massive efforts at social and economic reorganization, today’s children will inherit a world of unprecedented social dislocation, resource warfare, and mass die-offs. This future is already here, distributed disproportionately among the most globe’s vulnerable, and poised to steadily threaten even the most privileged – who are scrambling to insulate themselves as best and for as long as they can. As we marvel, stupefied, over the barbarity of ancient civilizations, or debate the supposed barbarity of present groups, our horrified, fixated cries of These people kill their own children, they deserve to be destroyed! carry an unspoken admission and correlative fear: As do we, and so do us.

***

Patrick Blanchfield is an Associate Faculty Member at the Brooklyn Institute Social Research. He is on Twitter as @patblanchfield.

***

“Political Feelings” is a column by Patrick Blanchfield about stories, scenes, and studies of religion in American culture published with support from the Henry R. Luce Initiative on Religion in International Affairs.