Spiritual Wellness as a Tool to Combat Racism

An excerpt from “Black Panther Woman: The Political and Spiritual Life of Ericka Huggins”

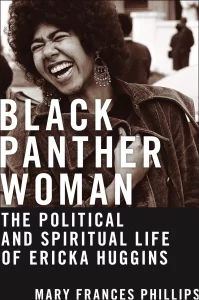

(Photo of Ericka Huggins. Image source: San Francisco Chronicle/Hearst Newspapers/Getty Images)

The following excerpt comes from the book Black Panther Woman: The Political and Spiritual Life of Ericka Huggins (NYU Press, 2025). The book explores the political and spiritual biography of a prominent female member of the Black Panther Party.

This excerpt comes from the book’s introduction.

***

In quick succession, I was barraged with questions. “Where are you located? Why are you choosing this topic? I’m assuming you’re an African American woman?” One after the other, the questions derailed me. I came to this experience as the interviewer, and yet, during my first conversation with Black Panther Party veteran, educator, poet, human rights activist, and former political prisoner Ericka Cozette (Jenkins) Huggins in 2010, I quickly learned that I was the interviewee. I soon discovered that this was not a typical researcher-subject relationship (if one exists). In our interview process, Ericka would interview me as much as I interviewed her; but in the moment, I was taken aback. I was the scholar. She was the subject. And yet, here I was explaining that I was a Black woman and daughter of Detroit, Michigan, passionate about centering Black Panther Party (BPP) women as frontline revolutionaries who intellectually contributed to Black Power theory. From this first interview, I knew that my place of origin, interest in BPP women, and racial background mattered in ways I had not considered. Neither one of us could relinquish for the sake of objectivity or scholarship our race, womanhood, or values. I had met my research subject, but more importantly, I met who would become my revolutionary teacher. Ericka offered historical context for our conversations, rooting our engagements in the racial system of US slavery and the history of civil rights women. She recommended books on the BPP for me to read and sometimes invited me to events on BPP women. As it turns out, she was not a research subject but a guide. What I had conceived of as interviews became conversations. Together, we weaved our dialogue, one that preserved our identities while simultaneously being open to critique and hard questions. These conversations revealed the convergence of Ericka’s social justice and spirituality, prompting me as the scholar-interlocutor to reconsider my preconceived notions of scholarship. To effectively capture the richness of Ericka’s story, this book required an entirely different scholarly approach—one that called for my active engagement and self-reflection alongside Ericka as I focused on what I call spiritual wellness.

Spiritual wellness encompasses a comprehensive framework that intertwines self-care and community care, operating on a scale from the local to the global, from everyday practices to revolutionary change. This book’s primary intervention lies in an examination of Ericka’s profound practice of spiritual wellness. I define spiritual wellness as Black feminist practice that interweaves community and self-affirming acts of care. Ericka engaged in spiritual wellness by practicing yoga and meditation, composing letters, writing poetry, and making community connections during her two-year imprisonment in the late 1960s. These spirit-based acts of service were forged to ward off the visceral and psychological impacts of racial oppression. While Ericka’s experience with state and federal violence, particularly her 1969 Connecticut arrest, catalyzed this lifelong spiritual wellness journey, seeds of this journey were sown early on in her childhood.

Spiritual wellness encompasses a comprehensive framework that intertwines self-care and community care, operating on a scale from the local to the global, from everyday practices to revolutionary change. This book’s primary intervention lies in an examination of Ericka’s profound practice of spiritual wellness. I define spiritual wellness as Black feminist practice that interweaves community and self-affirming acts of care. Ericka engaged in spiritual wellness by practicing yoga and meditation, composing letters, writing poetry, and making community connections during her two-year imprisonment in the late 1960s. These spirit-based acts of service were forged to ward off the visceral and psychological impacts of racial oppression. While Ericka’s experience with state and federal violence, particularly her 1969 Connecticut arrest, catalyzed this lifelong spiritual wellness journey, seeds of this journey were sown early on in her childhood.

Ericka began raising her political consciousness at an early age. She was born on January 5, 1948, in Washington, DC, in a working-class family. When she attended the March on Washington on August 28, 1963, as a fifteen-year-old girl, against her parents’ wishes, Ericka reached a turning point in her young life and vowed that she would serve humanity. Later, while attending college at Lincoln University, a historic Black university, she read a Ramparts magazine article on criminal charges levied against Huey P. Newton, BPP co-founder and minister of defense. Upon reading the story, Ericka and her partner, John, decided to leave college in the fall of 1967, move to California, and join the BPP. The BPP was one of the best-known and most misunderstood organizations during the Black Power movement. Founded in Oakland, California, in 1966, the BPP functioned as a grassroots political coalition-building organization and served as a political home for Ericka from 1967 to 1981.

Ericka’s Arrest

“I thought we were going to be killed,” Ericka recalled, when on the evening of January 17, 1969, FBI Counterintelligence Program (COINTELPRO) agents murdered her husband, John Huggins, and her comrade Alprentice “Bunchy” Carter on the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA) campus.8 Ericka was only twenty-one years old and postnatal when the state murdered her husband. Home alone the day of the shooting, Ericka noticed the police stationed outside the Black Panthers’ two-level apartment. Despite having just learned of the shootings of her husband and friend in cold blood, her concern instinctively shifted to her three-week-old daughter, Mai. Due to heavy police surveillance, Ericka feared for Mai’s life. After the rest of the Black Panthers returned to the apartment without John and Bunchy, Ericka recalled, “I rolled her [Mai] up in a big winter coat and gently placed her under a bed and said goodbye to her.” Loud noise and chaos filled the apartment. The police shouted demands, ordering Ericka and her fellow Black Panthers to come down the stairs. Cautiously, she removed Mai from under the bed. With a coat wrapped around Mai, Ericka descended the porch steps.

“Hold her up so I can see her,” one of the police officers demanded. He then pointed his gun directly at Mai.

“This is a baby! Put the gun away,” she pleaded.

“The baby might have a gun,” the officer retorted, scoffing at her concern.

Ericka lifted the coat to prove that she was holding a baby, leaving Mai’s two small feet to dangle. The police took Ericka with her baby and the rest of the Black Panthers into custody. Trusted friends picked up Mai, and the police transferred Ericka from the Los Angeles Seventy-Seventh Street police precinct to the Sybil Brand Institute for Women. She was released eight hours later. The police officers’ inhumanity resulted in state violence that spared no age or gender.

A Spiritual Childhood

“Who lives in me?” Ericka said aloud to herself at the tender age of nine as she looked in the mirror while diligently brushing her teeth. The morning sun beamed through the bathroom window. Her younger siblings, Kyra and Gervaze Jr., were still sleeping. Ericka was an early riser. The smell of her mother’s homemade biscuits, sunny side eggs, bacon, and grits wafted from the kitchen. She could also hear music from the small AM radio in the kitchen that played on until the end of each day. As she gazed at herself in the mirror, Ericka fell into her own eyes. It did not feel scary or creepy. Instead, she was curious. She felt that she was more than the tween looking back at her. There was more to her. Ericka needed answers. She dropped her toothbrush in the sink and ran downstairs to the kitchen, toothpaste still all over her mouth.

“Momma, momma, who lives inside my eyes?”

“Oh, Ericka, you having one of your questions again? I don’t know, Suga. Maybe it’s God.”

“Okay, Momma.”

When recalling this moment in her young life, Ericka released a full belly laugh. Ericka always asked lots of questions. Her mother often taught her that God lived in heaven and was not a figure that you could literally hold; God was infinitely complex and multitudinal. Even young Ericka knew that her mother was telling her in the best way she knew how, “God lives inside you.”1 While her mother did not fully answer the question, Ericka remembers how the query satisfied her curiosity that day and left a lasting mark. Her mother always had something helpful and healing to say. Even so, for years, Ericka continued to ponder the question.

When she was twelve years old, Ericka woke up in the bedroom she shared with her younger sister, Kyra. A deep question weighed on her mind: “Who am I?” She wrote the question everywhere—on a poster in large capital letters, on a poster that she and her sister used to draw on and decorate in their bedroom, and on the bathroom mirror. Then, she turned to Kyra.

“Don’t you already know? You’re Ericka,” replied Kyra, who was now nine years old.

“But, Kyra, there’s so much more to me and there’s so much more to you. Who am I?”

“You’re Ericka. Son of Gervaze and Cozette. You live on Fifty-Fifth Street in Southeast Washington, DC. You’re a Black girl and you’re tall.”

Kyra innocently and matter-of-factly pointed out the obvious, external aspects, but Ericka’s questions hinted at something deeper, something not so easily named or described. At twelve years old, Ericka’s soul was stirring, longing to identify her life’s purpose.

These youthful moments marked the beginnings of Ericka’s journey toward spiritual discovery. She came to understand the presence of a timeless, ageless, infinite power inside every human being, and that this power lived within her.

Mary Frances Phillips is a scholar-activist, public intellectual, and Associate Professor of African American Studies at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign. Her scholarly interests include the Modern Black Freedom Struggle, Black Feminism, and Black Power Studies.

***

Interested in more on this topic? Check out episode 58 of the Revealer podcast: “A Black Panther Woman, Spirituality, and Today’s Activism.”