Political Feelings

Soul Murder

“Political Feelings” is a bi-monthly column by Patrick Blanchfield about stories, scenes, and studies of religion in American culture.

On Tuesday, a Grand Jury in Pennsylvania released a report about seven decades of sexual abuse by Catholic clergy and systematic cover-ups by Church authorities. The report is the product of two years of investigation, encompassing dozens of witness interviews and the review of half a million pages of documents. Carried out in the face of opposition from two dioceses (Harrisburg and Greensburg, which sought to quash the investigation prematurely), it is the single largest such investigation in American history, naming three hundred priests as perpetrators, and establishing a tally of at least one thousand identifiable victims, many of whom were continually abused over the course of years.

The Pennsylvania report is being covered intensively by practically every major news outlet, with each publication’s reportage including multiple brief vignettes of abuse. The reason the cases summarized in each outlet are different is because there are hundreds upon hundreds of different episodes to choose from. Their horror beggars imagination. A priest rapes a young boy so violently he damages the child’s spine, consigning him to years of painkiller dependency, and ultimately to overdose and death. A priest rapes a girl while she is in a hospital bed recovering from having her tonsils out. A group of priests whip boys with belts and force them to pose for photographs, naked, as though crucified. A priest rapes a girl and then arranges for her to receive an abortion — with the subsequent blessing and sympathy of his superiors. The sadism and perversion the report documents is so heinous that readers with a Christian upbringing may find themselves reaching for the vocabulary of demons and the demonic. So too did one priest, who, in warning his superiors about a sexual predator colleague, described him as an “incubus.”

Despite that warning, that predator’s superiors effectively did nothing about it. And this is the other half of the report’s story: the revelation of sophisticated and elaborate mechanisms for shielding predators, avoiding public scrutiny, escaping legal accountability, and even punishing victims and families. Time and again, whistle-blowing clerics and parishioners (including some who worked in law enforcement) approached their pastors and bishops to report abuse, confident the Church would act decisively. And time and again, the reports were ignored or rejected, and abusive priests were transferred to other parishes, not infrequently being promoted and given even greater access to vulnerable children. These stories, too, beggar belief. When a father shows up to a rectory in Pittsburgh with a shotgun to confront his daughter’s abuser in the 1960s, the Church responds by sending the priest to a Church-run mental health facility for “evaluation” — and then assigns him to teach middle school in San Diego for the next two decades. When another priest dogged by child sex allegations eventually resigns, his superiors write him a letter of reference — for a job at Walt Disney World.

For seven decades, priests who were known, and self-admitted, abusers were laundered within the system. “The bishops weren’t just aware of what was going on; they were immersed in it,” observes the report. “And they went to great lengths to keep it secret.” Those lengths included “continuing to fund abusive priests, providing them with housing, transportation, benefits, and stipends— and leaving abusers with the resources to locate, groom and assault more children.” Indeed, in numerous cases, as the report makes clear, the Church lavished money on dubious “treatments” for abusers, and paid large sums to abusers in order ease their departure from the clergy, all while running out the statute of limitations clock on legal actions by victims and fighting over pennies necessary for their medical and mental health treatment. The report refers to this edifice of cover-ups and wrongdoing as “The Circle of Secrecy” — noting this phrase is not its own devising, but rather the coinage of former Bishop of Pittsburgh, Donald Wuerl.

For his part, Wuerl is no longer in Pittsburgh — he’s now Archbishop of Washington, D.C. But the Church in Pennsylvania’s response to the report is stunning in its own right. “Sadly, abuse still is part of the society in which we live,” writes Alfred A. Schlert, Bishop of Allentown. “We acknowledge our past failures, and we are determined to do what is necessary to protect the innocent, now and in the future.”

Perhaps Bishop Schlert is sincere in his concerns about “society,” though one might suspect that he and other apologists want to have things both ways — to keep the City of God at once hygienically apart from Earthly “society,” while also strategically shifting any blame for clerical misconduct onto contagion from it. But, in any event, let’s consider the abstraction of blaming “society” alongside the concrete details of the following episode, included in the Grand Jury materials, which occurred near Pittsburgh in the 1960s.

In his message, the victim revealed that while living in West Newton when he was around seven years old, he was told by a Sunday school teacher that missing mass could make you die. Concerned for his mother who was missing mass, the victim went down to the church to plead the case of his mother. The victim related that “Father Gooth” [Guth] took the victim into the rectory office where Guth sat in a chair as the victim stood before him, sobbing and pleading for his mother’s soul. Guth asked the victim whether he believed that Jesus suffered and died for our sins, in response to which the victim said “of course” as that is what he was taught. Guth talked about penance and having crosses to bear and asked the victim if he would do anything to save his mother. Guth then spoke of secret confessions and penance before reaching over and unbuckling the victim’s pants, pulling them down, fondling him, and sticking his finger up the victim’s anus. The victim believed Guth then spoke in Latin. The victim stated he was frozen stiff when the abuse was occurring and that when Guth was done, he was instructed to pull up his pants and that if he told anyone about the secret penance, not only would his mother go to hell, but he [the victim] would burn with her. Guth then gave the victim a nickel and warned him again not to say anything to anyone or his whole family would burn in hell.

Or consider this episode, which occurred in the very diocese of Allentown itself — Schlert’s current bishopric — back in the early 1980s.

The victim said that his first memory of abuse happened while he attended CCD [Confraternity of Christian Doctrine, AKA “Sunday School”] class at St. Bernard’s, where [Monsignor J.] Benestad was assigned. The victim was taken out of class by a nun and delivered to Benestad in his office. The victim had worn shorts to CCD, which was against the rules. The victim was told that shorts were not proper attire and that not wearing proper attire was sinful. The victim was told to get on his knees and start praying. Benestad unzipped his pants and told the victim to perform oral sex on him. The victim did as he was told. Benestad also performed oral sex on the victim. The victim recalls that, after the abuse, Benestad would produce a clear bottle of holy water and squirt it into the victim’s mouth to purify him.

Whatever the problems of “society” more broadly, it is impossible not to see in these horrors very particularly Catholic features: tropes, however twisted, of sin, penance, mortification, and punishment, concepts and ritual items wielded as tools of abuse. These priests, in other words, did not just rape children using their hands, mouths, and genitals. They also raped them using their faith.

***

I grew up around priests, and in the Church. I served as an altar boy, first in my local parish church and then in a cathedral, for almost ten years. I received an impeccable education from Jesuits, for free, a gift for which I am still grateful. To this day, I count priests among my friends. Liturgical music can still transport me, and the slightest whiff of incense — Jerusalem brand — opens up Proustian vistas of memory.

But I left the Church for good in the Summer of 2002. I was in Massachusetts, right as the first, explosive investigations of clerical sexual abuse were being made public by The Boston Globe. During the Sunday homily at my then-parish in Cambridge, the pastor read us a letter, sent by the Archbishop of Boston, Bernard Law. The topic was a legislative effort to add a so-called “Protection of Marriage Amendment” to the state constitution, which would have pre-emptively denied efforts to legalize same-sex marriage. Unsurprisingly, Law urged support for the amendment, in the most strenuous terms; it was our duty as Catholics, a decent people with family values, to pressure our legislators accordingly.

Our pastor read the letter, and then, to his credit, spoke briefly for himself. In so many words, he admitted that he only read it because he had to, and that he felt uncomfortable with it. He expressed particular hesitation with the linchpin of Law’s argument: that same-sex marriage would be “damaging to children.” In light of breaking news about the Diocese’s history of covering up sexual abuse, and particularly given our parish’s thriving youth choir program, he felt it was not his place, let alone Law’s, to make any such pronouncements.

I forget the exact words the priest used, but I suddenly felt moved to tears by his candor and even bravery. I also found myself realizing, with almost crystalline clarity, that I was crying about something else, too: that this was it for me, that there was nothing there for me, that I wanted no part in an institution that could produce such a scene. The contortions of loyalty and pain, the suffering it generated and the empathy it at once made possible and denied — I couldn’t bear it. I don’t remember if I left while everyone else shuffled around for communion. But I do remember walking out and telling myself not to look back.

To be sure, I was never, in retrospect, or even as I saw it at the time, a “Good Catholic.” In fact, to be perfectly frank about it, the phrase and idea of being a “Good Catholic” always struck me, if not as an oxymoron, than at least a kind of provocative irony. The very core of Catholicism as I was raised in it hinged on a self-critical, precarious relationship to the idea of goodness. Your Goodness as a Catholic was always ever only provisional, contingent upon a logic of confession and atonement in this life, and of final judgment in the next. At one point, in a theology class, a priest asked us what our favorite words in the liturgy were. I knew the whole thing by heart, and my response was immediate: “Lord, I am not worthy to receive you, but only say the word and I shall be healed.” These words are said right before Communion — or at least they were (a recent update to the English liturgy brings the expression closer to its origin in Matthew 8:8). They paint a poignant picture: the finite human, mortal and frail, begging only a single, transformative gesture of healing from the infinite divine.

Reading the Grand Jury report today, those words keep coming back to me. Their power still speaks to me, but now I detect something else in them. On the one hand, they express a posture of beseeching receptivity towards the Divine; on the other, they signal profound vulnerability to all-too-human abuse. The episode in West Newton, with the child begging for intercession on behalf of his mother, looms. How vulnerable is a seven year old, burdened with the ontological guilt of Original Sin, and navigating an austere calculus of punishment according to which his mother can go to hell for missing Mass? If you carry within you some basic fault, some constant taint of dirtiness and shame, does it not follow that further debasement is somehow inevitable? That you can never be entirely sure if you’re getting what you deserve — or what you want? Or that, in the muck and sinfulness of your humanity, if goodness and healing were to come you, you might mistake them for exploitation and filth — or vice-versa?And if the whole enterprise of sin and forgiveness is so over-coded by themes of concealment and privileged divulgement — the very logic of confession — does that flow seamlessly into relationships of being groomed and then keeping silent — of understanding that You Keep The Secret, or You go to Hell?

I should say: I was never abused. The closest I came was a strange encounter with a layperson CCD instructor, a stockbroker in his thirties, in what was supposed to be some sort of Sex-Ed/theology class, yelling at me and some other pubescent boys, veins popping in his neck, about how “JESUS DIDN’T GET NAILED TO A TELEPHONE POLE SO YOU COULD DROP YOUR SHORTS.” My friends and I just looked at each other, completely uncertain what the guy was talking about. The priests my friends and I knew, as altar servers and teachers in our all-boys school, were nowhere near as florid or erratic. And besides, you made allowances for priests — didn’t you have to be a little weird, a little “queer” (in the old sense), to become one in the first place? Their frequent oddity was part-and-parcel, a necessary evil, so to speak.

Of course, some were weirder than others. The priest who was a little too enthusiastic about hugs; The priest who was always hanging around groups of athletes, who was always ready with pats on the back after a game, who had clear favorites on the team, who would sometimes massage a boy’s shoulders. The priests we made snickering jokes about in locker rooms; jokes that served, not coincidentally, to defuse and redirect pervasive homosocial tension.

To be clear, I do not think these men ever crossed certain lines — or at least, I do not know if they did. For what it’s worth, they never seemed predatory. The affect they broadcast instead was more a kind of sadness. You could see it when they didn’t think we were watching. Glimpses in their eyes and faces of deep loneliness and frustration, the tells of bodies and souls too-long macerated in yearning and lack. The sadness they’d struggle to disguise when talking of former colleagues and seminarian friends who had left the cloth behind to marry women, and, in at least one case I knew, to marry a man. The same tonalities of sadness you might sometimes perceive learning of the priests who, having given up possession of significant worldly assets, spent their meager funds overindulging on liquor and tobacco and fatty food.

I leave it to others to address the delicate questions of how celibacy or the oppression of the closet are implicated in clerical abuse. Likewise, I cannot stress enough there is to be no question of excusing such behavior in the guise of “explaining” it — if anything, as the Grand Jury Report documents, this bait-and-switch has been an integral part of the Church hierarchy’s own cynical publicity M.O. for years. By the same token, we must always reject as obscene any attempt to equate sexual abuse to non-heterosexual orientation (another classic misdirection). After all, as the report makes painfully clear, the targets of abuse in Pennsylvania included not just boys but girls too, both women and men. And the psychology research on sexual predators is unequivocal: abuse is first and foremost about availability and vulnerability — it is about power, and about being able to get away with it.

But, again, there is something in the episodes the report contains, something that resonates with the core of my experience of Catholicism — and I suspect I am not alone. A particular configuration of innocence and guilt, of expiation and profanation, that suggest some deeply flawed, corrosive worldview, a sadistic-erotic matrix of pleasure, suffering, secrecy, and guilt. This suspicion is underscored every time some Bishop or professional apologist circles the wagons and takes every discussion of abuse or abusers as an assault on Catholicism itself. What if, you start to wonder, in some way — they’re right? What if, in a basic way, these outrages are not incidentally Catholic, but essentially so? And what are we supposed to do, then?

Reading the report, I feel many things at once. Part of me wants to smash altars with a sledgehammer. Part of me wants RICO investigations into every archdiocese and diocese in the country. And part of me wants a priest to put a hand on my shoulder while I cry, to tell me that everything will be all right, that these were not real priests, that all this, somehow, can made understandable and redeemed in light of God’s love.

No matter what I do, there’s some part of me that wants nothing more than to feel the forgiveness of Grace, some feeling of total forgiveness, acceptance, and love that undoes the most basic of faults. I feel this even as I understand that, in large measure, that conviction of a fault in the first place is something that was put in me by the institution that I want to heal it. What the Church shaped in me was a conviction of fallen-ness, of broken-ness, of sinfulness, of a fundamental pain and tragedy and unworthiness written through all of human existence that cried out for the healing transformation of grace. And what the Church took from me was the belief that any such transfiguration was possible through it. Reading the Grand Jury report, I suspect that, in this too, I am not alone.

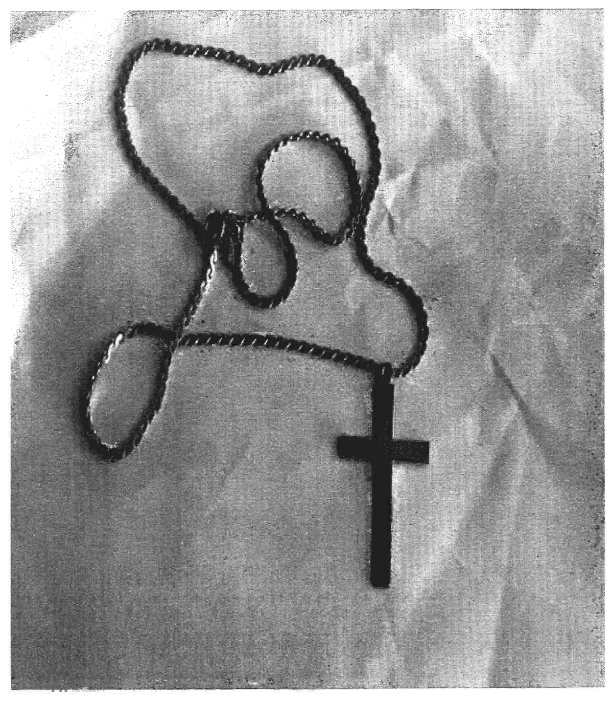

One of the gold crosses given by Father George Zirwas, member

of a clerical pedophile ring, gave to altar boys he abused.

***

Patrick Blanchfield is an Associate Faculty Member at the Brooklyn Institute Social Research. He is on Twitter as @patblanchfield.

***

Published with support from the Henry R. Luce Initiative on Religion in International Affairs.