Son of Safam

What a musical nostalgia trip taught me about the roots of my Jewish identity

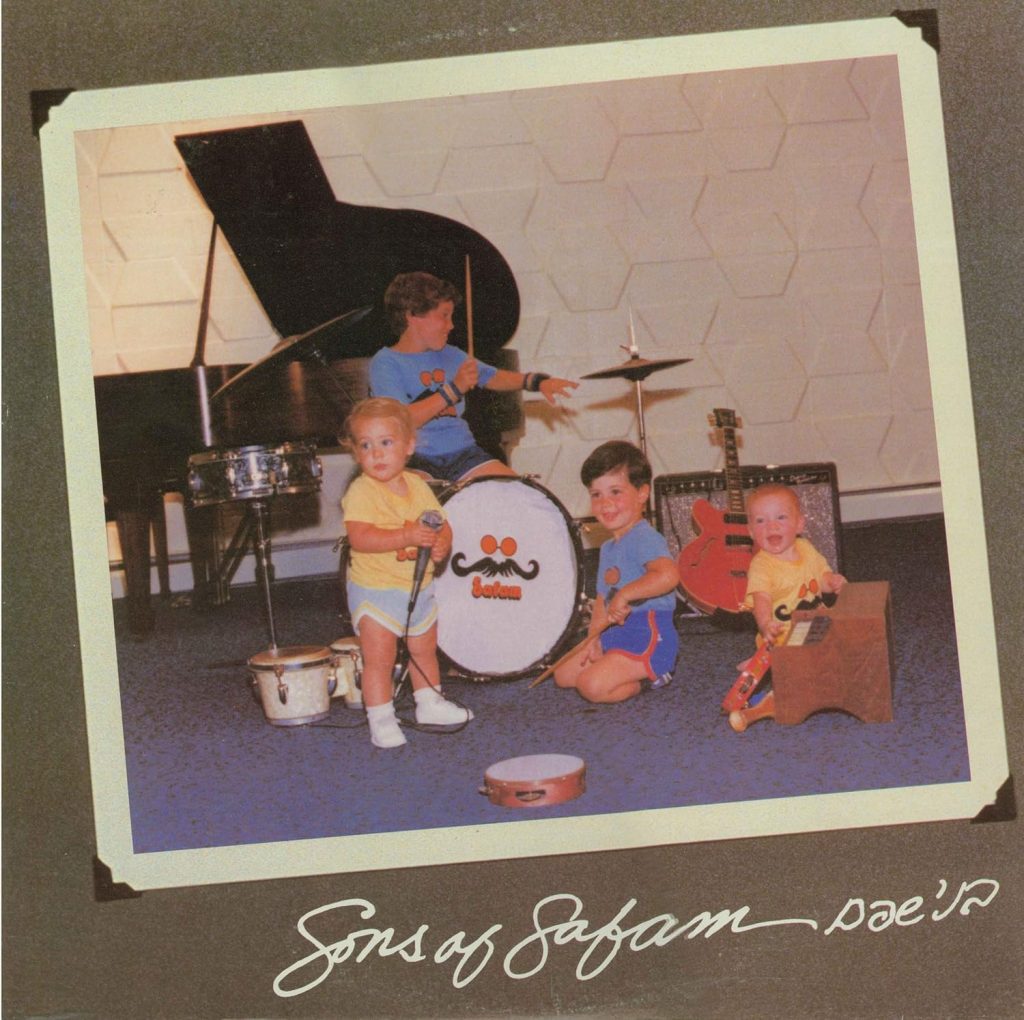

(Sons of Safam album cover)

My Bar Mitzvah tour had a theme song.

This was 1994, my first time in Israel. And I did all the things any good young American Jew ought to do on a whirlwind trip: I kissed the Wailing Wall; placed stones on the graves of war heroes; sobbed at Yad Vashem, the Holocaust memorial museum; recited Torah atop Masada; danced the hora while cruising Lake Kinneret; and developed a fast crush on one of the Bat Mitzvah girls.

By the end of the trip, our guide had the entire bus singing and swaying along to Israeli singer Chaim Moshe’s anthemic pop ballad “Todah,” even if most of us couldn’t understand the bittersweet lyrics:

Todah al ma sheli natata / Al yom shel osher / T’mimut v’yosher / Al yom atzuv she-ne’elam [Thank you for what You’ve given me / For a day of happiness / Innocence and honesty / For a sad bygone day that has vanished].

I hadn’t thought about “Todah” since I was a teenager. Until one frigid winter night, back in 2017, I fell into one of my listening rabbit holes. Beginning with some Israeli jazz and folk music, YouTube’s algorithm serendipitously led me to “Todah,” before alighting on another blast from the past: “World of Our Fathers,” by the Jewish-American group Safam.

Here it was, my musical madeleine. Suddenly I was transported to the back of our old family Toyota, my brother Andy sitting across from me. We were on one of our frequent Pittsburgh road-trips, and my parents were asking which Safam cassette we wanted to hear. It was usually Sons of Safam, though we would have insisted on starting with the B-side, so our favorite song “World of Our Fathers” would come faster.

Hearing Safam again for the first time in decades, I immediately broke down crying. Though it doesn’t take much for movies or music to make me weepy, this reconnection with Safam was something different, far more powerful: it felt like coming home. But what was I coming home to?

***

Safam (Hebrew for “mustache”) was founded in Boston in 1974 by Boomers Dan Funk, Alan Nelson, Robbie Solomon, and Joel Sussman—friends from the Zamir Chorale, Boston’s celebrated Jewish choir. Though a labor of love, the band was always a side project; only Solomon would pursue music professionally, as a cantor and composer.

Despite their disparate day jobs, what united Safam’s founders, beyond their mustaches, was a similarly observant and loving Jewish upbringing (Funk’s father was a rabbi, and Solomon was raised Orthodox). The music the group recorded and performed over the next quarter century translated their passion for Judaism into a comprehensive vision for Jewish-American life. It was a winning formula. In the early ‘80s, Safam enjoyed a meteoric rise into the rarefied orbit of Jewish-American pop culture, at least in the Northeast. Funk, in an interview on the band’s 40th anniversary, characterized Safam in its heyday as a “Jewish supergroup.”

(Safam “On Track.” Image source: Spotify)

What was it about Safam’s music that resonated so deeply with my family, especially considering that half their repertoire was in Hebrew, which we didn’t speak? Unlike, say, Shlock Rock—Safam’s contemporaries on the synagogue circuit, who delighted audiences with silly parodies of classic rock hits (like “Every Bite You Take,” in case you ever wondered how it would sound if The Police had sung about Jewish dietary law)—Safam was unique. Whether jazzing up mainstays of the Hebrew liturgy, or composing original torch songs like “Leaving Mother Russia,” Safam’s rousing “rallying cry for the Soviet Jewry movement” and their best-known song, the band had a recognizable sound all its own.

But this sound transcended the group’s diverse Jewish musical roots—Chasidic, klezmer, Israeli folk. It was, fundamentally, a Jewish-American sound (“The Jewish-American sound,” per Safam’s tagline). Drawing on a range of popular styles, Safam crafted a musical language that perfectly captured the experience of Jewish kids like me: a fourth-generation, middle-class suburbanite, thoroughly acculturated into mainstream American life while still eager to celebrate my Jewish heritage. Growing up, going regularly to synagogue, it was always the music—the rich, haunting minor-key melodies that unfurled each Shabbat morning—that helped me feel most tightly connected to Judaism. Safam delivered that very feeling, but sonically repackaged in the familiar musical vernacular of American folk and ‘70s and ‘80s pop rock.

***

In the weeks after rediscovering Safam, I became obsessed with the music’s sweet sentimentality, which conjured a bygone Jewish childhood: Chanukah candles, Purim carnivals, Hebrew School puppet shows, raucous family seders.

Andy happily accompanied me on this listening journey down memory lane. My family used to discuss Safam members like other music fans would argue over their favorite Beatle. My mother swooned over Solomon, with his lush cantorial tenor. Andy reminisced about meeting the band after one of their concerts: “I got them all to sign the back of a record album, and I told Robbie Solomon I was his biggest fan.”

We soon exhausted the limited selection of Safam’s music available online. But Andy surprised me by ordering the complete 10-CD set of Safam’s albums from the band’s antiquated website for my birthday. I was overjoyed. Handing me the gift, he declared: “Nostalgia, here we come!”

***

Safam released their debut album, Dreams of Safam, in 1976. Two years later came the more polished Encore, which showcases an ambitious synthesis of the band’s eclectic influences—from biblical stories to bossa nova and barbershop sounds.

Yet it is Sons of Safam (1980), their third album, that will always stand out to me as their quintessential work. While I suppose it was the jubilant music that moved me as a child—I distinctly remember dancing to the tight jazz-funk groove of “Judah Maccabee”—I was struck this time by the album’s thematic consistency.

Released after several band members had become fathers, Sons of Safam is, primarily, about blessings. But it is also about Jewish continuity: the blessings fathers recite to their sons, so they may pass them down to their own sons one day. These themes converge in the album’s lovely (if cloying) title track, as Safam’s vocalists take turns sanctifying the new generation. The chorus even concludes with a cheeky prophecy: “Ani ro’eh yavo hazman / Yitahadu kulam / V’kol echad yashir shirei Safam [I see the time will come / When everyone will unite / And everyone will sing the songs of Safam!].”

The flip side of the album’s earnest optimism is its deep concern over how easily Jewish life can slip away across the generations. Heard in this light, I now realized, “World of Our Fathers” is a cautionary tale—Safam’s moral plea to American Jews like me.

Set to a lilting acoustic guitar line reminiscent of Simon and Garfunkel’s “The Boxer,” the song—likely an homage to the eponymous Irving Howe book—relates a familiar Jewish immigrant story. Not unlike my own great-grandfather, the narrator arrives at Ellis Island from Russia and—peddling, scrimping, and saving—builds a life for himself in America.

Despite his best efforts to keep the flame of Jewish tradition alive, the “little citizens” he raised—bent on transforming themselves into “sophisticate Americans”—ultimately shun their first-generation father. “Just don’t forget where we came from, my children,” he sings out, if anyone is listening. “The world of our fathers is what made us strong.”

Redemption comes late. Now living with one of his grandchildren (a doctor!), the narrator observes a rekindling of Jewish spirit in the newest generation: “There were times, so many times, when I feared that all was lost / We had come so far, so fast, that I wondered what the cost / But now I see my father’s world begin to rise / In my great-grandchildren’s eyes!”

With four heart-shredding clarinet notes, the song erupts into a boisterous klezmer finale. It’s as if the song’s rollicking refrain (“Yai dai dai in America”) sardonically suggests that, in America, one must choose: cast aside Jewish life, or lovingly nurture its blessings and pass them along to future generations. Listening obsessively to “World of Our Fathers,” I heard Safam asking: Which side are you on?

***

I didn’t have a good answer to Safam’s question.

If my Bar Mitzvah in Israel marked the pinnacle of a robust Jewish identity that had been cultivated from my earliest Hebrew School days, it also unearthed some vexing questions. One memory in particular continues to haunt me.

On our first Shabbat in Jerusalem, our tour group headed to the Wailing Wall for an evening service. As our well-worn American-Ashkenazi melodies filled the air, the golden sun setting before us, I sang my heart out. Chanting Shabbat prayers at the holiest Jewish site on Earth, I felt as if it had never been more wonderful to be Jewish.

Before long, however, several Orthodox men started berating us. The problem was that our prayer group intermixed men and women; it didn’t matter that we were hundreds of feet from the Wall. The religious police eventually broke up our service but, ironically, allowed us to continue closer to the Wall, inside the gender-segregated enclosure, where we could hear but not see our fellow worshippers across the partition.

While the tour fulfilled the unstated purpose of many such Bar Mitzvah trips—I did fall in love with Israel over two short weeks—this episode left an indelible blemish on my relationship to the place. Why were my fellow Jews so intolerant at the very moment my religious pride was at its peak?

I drifted further from Judaism in college, no longer keeping kosher and rarely observing holidays. As a history major, now fashioning myself a cosmopolitan humanist (one of those “sophisticate Americans”?), I became suspicious of any particularistic identity. My college years also coincided with the Second Intifada, a large-scale Palestinian uprising that unleashed cycles of brutal violence and triggered a new phase of increasingly oppressive Israeli policies in the Occupied Territories. It was against this backdrop that I took my first Middle East history course, which challenged many of my assumptions about the Israel-Palestine conflict. With mainstream American Judaism doubling down on its staunch support for an increasingly rightwing Israel during these years, I grew doubtful I would ever feel at home again in my Jewish identity.

My alienation only intensified when I returned to Israel in 2005, eleven years after my Bar Mitzvah. Now living in Egypt as a graduate student, I took a short flight to visit my Orthodox cousin, who had immigrated to Israel. Although I had a wonderful time with her family, it was impossible, on the heels of the Intifada, to ignore the pernicious political climate. On two separate occasions people asked if I was a suicide bomber—ostensibly because I was a bearded man of a certain age entering a bar or restaurant alone.

My last morning, strolling along the Tayelet Haas Promenade overlooking Jerusalem’s Old City, I met a kindly old man named Israel, who lived nearby. He pointed out the military’s security wall snaking along in the distance and lamented the havoc it would wreak on his Palestinian friends living in the adjacent villages. Seeing Israel through Israel’s eyes made the Occupation real for me, catalyzing a more pointed political education that for too long I had been reluctant to receive. And with a third Israel trip five years later—capped off by a vicious fight with my cousin’s family over the Israeli blockade of Gaza—my relationship with Zionism felt unsalvageable.

At that time, I simply didn’t know how to sustain a Jewish identity without Israel at the center of it. Jewishness and Zionism had always been so thoroughly imbricated for me that jettisoning the latter seemed to necessitate severing my connection with the former.

Once I settled in New York in my thirties, however, I found myself yearning for Jewish life once more. Aware I had lost some essential part of myself, I met with a rabbi and explored different Jewish communities. I began to hope I might find a little home within the Jewish universe, though the American Jewish community’s unwavering institutional support for Israel still left me doubting whether I truly belonged.

***

Safam’s music—with its sweet but solemn message about Jewish continuity—came back into my life during this period of soul searching and hit me especially hard.

As Andy had predicted, the music aroused powerful nostalgia—for the peppy, earnest ‘80s and tight-knit family togetherness of my childhood. But it also made me long for a time when my Jewishness felt safe and pure. Behind the happy memories that Safam’s music evoked was a sort of prelapsarian wholeness that I had lost and now suspected I would never recover.

Anthropologist Jonathan Boyarin has documented how “the ‘loss’ of one’s children to a different cultural world, common as it may be, remains in large measure an unalleviated source of pain” for Jewish diaspora communities. But what has typically been overlooked in such discussions is the pain of the children—those who carry the guilt of endangering Jewish continuity by opting for different cultural (or, indeed, political) worlds—which is precisely what I felt so intensely listening to “World of Our Fathers.”

The unbridgeable gap between the memories of my own warm, uncomplicated Jewish past, symbolized by Safam’s music, and my estrangement from American Jewish life in the present seemed like an unforgivable breach of responsibility. I couldn’t help feeling like I had let my family down, and Safam, too.

***

So I kept going back to their music, desperately clinging to the spark of Jewish connection it rekindled in me.

With Safam’s fourth album, Bittersweet (1983), the band moved in a new direction. As the title suggests, the mood started to feel a shade darker—a trend that continued through their next releases, Peace by Piece (1984) and A Brighter Day (1986). While the hopefulness of their earlier work was still present, the group waded into some knotty thematic terrain, from the elusiveness of Middle East peace to the guilt and despair of a Holocaust survivor. Hearing Safam urge us to “use the bitter with the sweet,” it seemed like their vision of Jewish life had grown more complex.

While I could get down with Safam’s unique brand of Holocaust pop/rock, I had a much harder time with their overtly Zionist material. One night, getting deeper into Bittersweet, I was grooving along to “Yamit”—a propulsive, vaguely Middle Eastern rock number that features one of Safam’s most hummable melodies. My musical ear tends to tune out song lyrics, but when I started paying attention to the storyline, I was horrified.

Yamit was a short-lived Israeli settlement established in the Sinai Peninsula after the 1967 War. In 1982, in fulfillment of the Egyptian-Israeli peace treaty, Israel’s military forcibly evacuated some 3,000 Israeli settlers from Yamit and bulldozed it to the ground.

“Yamit” was Safam’s bittersweet lamentation for the lost Israeli enclave. While the song conveys hope that the withdrawal will help deliver lasting peace, the tone is undeniably melancholic. The wistfulness of the reluctant evacuees is voiced most plaintively by a young girl, “too young to understand” what is happening, much like the “simple child” of the Passover seder: “Can we ever go back again?” she asks.

While “World of Our Fathers” had me imagining Safam’s disappointment over my faltering commitment to Jewishness, now I found myself disappointed in Safam. As a Middle East historian with strong objections to Israel’s settlement movement, I struggled to reconcile myself to a Safam that would memorialize Yamit like this.

Zionism was not a feature of Safam’s music I had consciously registered growing up, but now there was no denying it was a key ingredient in the potent Jewish-American alchemy embodied in their work. If listening to their music initially felt like a homecoming, I now realized, this was because it transported me to a more innocent time when Zionism did not yet appear to me as a political belief, but rather as an implicit cultural identity. I had been reflexively shaped by Safam to believe there was but one overarching Jewish story we all shared—one that necessarily leads, as another of their catchiest songs has it, “home to Jerusalem.”

***

At the height of my Safam binging, in 2017, I sensed there was still unfinished business for me in the Holy Land. If nothing else, I felt a moral and professional obligation to visit the West Bank; my teaching about Israel/Palestine seemed woefully inadequate without having a more granular understanding of realities on the ground in the Occupied Territories.

My first night in Israel, wandering jetlagged around Jerusalem, I followed the distant sound of drums and horns in Nachla’ot, the colorful neighborhood where I was staying. It was the second night of Chanukah, and I found myself in the middle of an exuberant street party. The revelers accepted me instantly; before I knew it a shot of whiskey had been placed in my hand. I stayed for over an hour, intoxicated by the community spirit, the gorgeous improvisational music, and the festive singing and dancing.

How wonderful it would be to claim this, I thought—to feel truly at home in this transcendent, all-embracing Jewish-Israeli space. One of the party’s organizers, the sort of Orthodox hipster who was ubiquitous in Nachla’ot, seemed to read my mind: “There is a prophecy,” he said, gesturing first towards me, then the crowd. “One day all the Jews of the world will come together and dance in the streets of Jerusalem.” I soaked it all in, sublimating my misgivings and opening myself one last time to Zionism’s seductive siren song.

Several days later I went to the West Bank. I toured the unspeakably depressing old city of Hebron, which the Israeli military had ruined under the pretext of protecting a tiny coterie of Jewish settlers (several of whom hounded us and threatened our guide, a volunteer with the Israeli NGO Breaking the Silence). I spent a wonderful day in Ramallah with my Palestinian friend Sa’ed, who introduced me to the beauty and vibrancy of his hometown, while also pointing out the fortress-like Israeli settlements flanking it on all sides—an unrelenting reminder of the Occupation.

The education that had begun when I met Israel on the Jerusalem promenade, twelve years earlier, now felt complete.

***

As alluring as I found the Nachla’ot prophecy that magical Chanukah night, I recognized its twinned ideals of Jewish unity and Zionist belonging to be at best a comforting illusion, at worst a dangerous trap. It may be true that all nationalisms pretend “we are one” (the refrain of another Safam earworm). But Judaism, unlike Zionism, is not a nationalism. Judaism is a rich and complex ancient faith tradition that contains multitudes; Zionism, a distinctly modern political ideology, is but one current in the vast ocean of Jewish history. Even if Jewish tradition is animated by a notion of common peoplehood, the fact remains that Jews have never been unified in religiosity, culture, or politics.

Nor would it be healthy or desirable if we were. As the philosopher Kwame Anthony Appiah writes, “The unities we create fare better when we face the convoluted reality of our differences.” Seen in this light, the question “Can we ever go back again?”—the nostalgic lament in “Yamit,” and the sentiment at the heart of so much rightwing nationalism—leads to a dead end, given its fixation on only one legitimate Jewish pathway, towards one authentic homeland. Regrettably, clamor for such narrow, rigid nationalist loyalty tends to increase dramatically in times of collective trauma and fear—as we’ve witnessed across the Jewish world since the horrors of October 7, 2023.

I don’t believe in nationalism, but I do believe in music as a kind of borderless homeland. All nationalisms, including Zionism, trade in reductive myths of past wholeness and unity, partitioning the past and holding us apart from one another in the present. Music, by contrast, has the uncanny power to bring us closer together, bridging cultural difference by conveying universal feelings of longing, loss, and hope. I hear this quality in Safam’s music, with all its joyful eclecticism and earnest melancholia, even if it is often overshadowed by the Jewish and Zionist particularism of the lyrics.

Reconnecting with Safam put me back in touch with parts of my past I didn’t know I could still access—a nostalgia trip that at once enticed and repelled me in equal measure. At the same time, it sparked a more honest reckoning with my Jewish journey by illuminating those elements of my upbringing that had once made it seem impossible to claim a Jewish identity bereft of Zionism. For this, to borrow Chaim Moshe’s words, I say to Safam: Thank you—for what you’ve given me; for a day of happiness, innocence, and honesty; for a sad bygone day that has vanished. After all these years, in spite of it all, to be wrestling again with my Jewish identity finally feels like home—and exactly what is required of me at this agonizing moment in history. This is a blessing.

Matthew H. Ellis is a historian specializing in the modern Middle East and North Africa. He currently holds the Christian A. Johnson Endeavor Foundation Chair in International Affairs and Middle East Studies at Sarah Lawrence College.