Sex Workers and Spirituality in the Catholic Church

Sex workers, from prostitutes to OnlyFans stars, have much to offer the Catholic Church if the Church would welcome them without judgment

(Image source/credit: Brian Wong for Getty Images/Xtra)

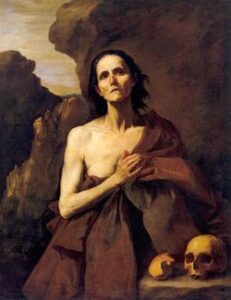

Mary of Egypt, a fourth-century woman venerated as a saint in the Catholic Church, once stowed away on a boat bound for Jerusalem and proceeded to have sex with every man on the ship. Or so the legend goes—details about this oft-forgotten figure are transmitted with less-than-perfect consistency across scattered manuscripts. She is often identified as a prostitute, and like other reformed “holy harlots” and “loose women” of traditional hagiography her sanctity comes at the expense of precisely that which led her so deeply into sin, namely, her sexuality. Many artists present her bare chest flat like a man’s, underlining the extent to which Church authorities deemed it necessary to unsex her before she could be revered as a saint.

(Mary of Egypt by Jusepe de Ribera)

And yet, the legends make clear that Mary never fully took leave of her sexuality. When Zosima, an old ascetic monk in search of new feats to test his faith, searches for her in the desert, the first thing she arouses in him is desire. In such stories, her bodily vigor amplifies, rather than detracts from, her spiritual authority. Commenting on the legend as it appears in a definitive twelfth-century text, the medievalist Irina Dumitrescu observes that “there’s a sense [in the legend] that sexual love is a stepping-stone to love itself [i.e., to love of God], not its opposition.” What Mary learned in the desert, then, was a way to direct the voraciousness she once had for the sailors towards God instead.

In Mary of Egypt, the early Church held up for veneration a woman who knew sexual desire, shame, and grace – knew these things well – and whose past exploits provided the fertile soil out of which genuine spiritual wisdom was able to grow.

***

Prostitutes and sex workers are not likely to find the same kind of understanding from the Catholic Church today. The Church tends to think of sex workers chiefly in terms of their supposed sexual sin (in this they are similar to non-celibate queer people or to some extent the divorced and remarried). Their identity, often reduced to an act, obscures the full scope of their personhood and prevents their complete participation in the ecclesial community.

For this article, I spoke to a number of current or former sex workers as well as Catholic priests, nuns, and activists who are or have been involved in outreach to sex workers. Nearly all spoke to the feelings of shame and neglect that sex workers feel in typical church settings.

And yet, I also discovered that many sex workers have managed to make their own space in the Church, or at least to find their own way into some kind of spiritual practice. Unsurprisingly, plenty of sex workers have no interest in religion; indeed, many have good reason to be suspicious of or hostile towards organized religion. The Church should therefore rethink its language about and approach to sex workers, not only for the sake of better recognizing their inherent dignity, but also to absorb the lessons they can teach about the resilience of faith.

***

The inhospitality that many sex workers experience in Catholic communities comes about as a result of a twofold invisibility that is simultaneously theological and pastoral. According to standard Catholic theology, sex work contradicts the ideal moral order where sex is only permitted within procreative, marital unions. Pastorally, the Church only sees sex work as a form of exploitation, not as a legitimate type of labor one might willingly choose. This latter point presents an obstacle to Catholic support for basic worker safety guarantees, such as unionization, despite the Church’s avowed support for worker solidarity in other realms.

Sex workers therefore find themselves in a double bind: neither their “sex” nor their “work” is allowed the dignity these categories otherwise hold within Christian ethical thinking, since if they engaged in it willingly, then they are morally culpable, and otherwise they are seen only as victims. Hille Haker, a leading Catholic ethicist, notes in a recent study that within Christian approaches to sex work, “prostitutes are predominantly viewed as passive victims who are involuntarily engaged in sex work.” This view is summed up in a Vatican document that describes sex workers as “dead [both] psychologically and spiritually.”

There should be no doubt, of course, that a great many sex workers come to the job unwillingly. Large percentages of the women in prison for prostitution are also dealing with drug problems, mental health issues, or a history of sexual abuse (typically at the hands of fathers or husbands). A vicious cycle can develop in which sex work becomes a means to support a drug addiction, or drugs become a means of tolerating the demands of sex work. Edwina Gateley, a Christian theologian who worked with sex workers for decades in Chicago, told me that none of the women she met grew up “dream[ing] of being a prostitute.” And yet to describe these women as “spiritually dead,” as the Church does, only adds insult to injury. In fact, Gateley said these women often displayed a deep and “profound” awareness of God’s presence within them. “[They were] more spiritual than most Catholics I knew!” Gateley said. She recalls accompanying police on a raid of a busy Chicago brothel where she noticed small icons on some of the women’s bedside tables. “I ain’t got nothing,” one of the women told her, “but I got God and God’s going nowhere.”

(Image source: Aidan Jones)

For these sex workers, God is not an object out in the world—indeed it is “the world” that very often brings threats of violence, scorn, and judgment. Rather, God is an immediate and immanent reality, one that they place themselves in and in whom they find the peace of consolation, even a kind of acceptance. They’re drawn less to the formal rites and rituals of organized religion than to unselfconscious dialogue with God in prayer, although many did find the trappings of traditional religion helpful. An old rosary or a prayer card kept in a pocket helped center some women while they walked the street or waited for their next client. Faith sharing groups and prayer circles – whether these were self-organized or operated out of shelters like the one Gateley ran in Chicago – provided a chance for sex workers to share burdens and build solidarity. These women didn’t want to talk to a priest in a stuffy parish office, much less in a dark and lonely confessional, but they were comfortable talking to one another. Many sex workers also incorporated non-Western meditation and alternative rituals into their spiritual practices, especially those that offered to integrate body and spirit since their work often requires compartmentalizing these two aspects of one’s personality.

Most of the sex workers I met cared more about finding community and acceptance than participating in mass and the sacraments. The pomp and ceremony, some said, felt too much like an effort to impress or intimidate. When you spend all day dealing with clients who lie to you, pimps who manipulate and abuse you, and cops who threaten to arrest you, regulated worship can seem like one more performance you’re expected to give. Several of the Christian activists and pastors I spoke with explained that their emphasis when dealing with sex workers was one of accompaniment and advocacy, rather than proselytizing or attempting to “rescue” them (although the language of emancipation and rehabilitation remains the default within Christian ministries aimed at sex workers).

The sex workers with whom I spoke who describe themselves as Christian see God as love, but rarely find that love reflected in the Church, which they largely view as a place of judgement. It’s not that these individuals have no concept of sin—quite the contrary. But to their minds the stronger, more compelling message is grace. Reflecting on the women she’s worked with over the years, Gateley commented that, “They’ve got beyond the [message of] condemnation to the [message of] love.” In their persistent, even insistent, faith they challenge the Church to consider how it ostracizes the people it is trying to reach.

***

Of course, to speak of sex work in general terms always risks over-simplification. “Prostitution is not a single thing,” as the philosopher Martha Nussbaum has argued in a classic article about the ethics of sex work. At some level, Nussbaum points out, every worker is engaged in the act of selling their body, whether on a factory floor, at a university lectern, or in a bordello bedroom. Moreover, there is a vast difference between the woman who has been the victim of human trafficking and forced into prostitution, the high-end escort who is hired out through an agency, and the middle-class college student who earns cash as a “cam-girl,” despite the fact that all of these could be described as sex workers (the latter category in particular exploded during the Covid-19 pandemic, with the subscription service website OnlyFans growing 553% in 2020). Nussbaum’s point is that the stigma attached to prostitution obscures the real economic and social pressures (and incentives) that lead people into such work. Along with several other feminists, Nussbaum has argued for greater legal and social acceptance of prostitution. On the other side of such debates are so-called “radical feminists” – most famously Andrea Dworkin and Catharine MacKinnon – who characterize all sex work as equivalent to rape and see no plausible degree of agency in such transactions.

It is ironic, to say the least, that the Catholic Church’s official thinking mirrors the radical feminist position, even while the Vatican elsewhere denounces the dangers of “radical feminism” and “gender theory” with a vengeance. In any event, both radical feminists and Vatican critics of sex work fail to distinguish between the diverse experiences of sex work, the different forms it can take, and the various economic factors involved.

When Covid-19 lockdowns all but eliminated in-person sex work during the early months of 2020, sex workers in New York quickly organized housing relief and emergency funds for one another, carrying on a long tradition of mutual aid in the sex work community that goes back to Marsha P. Johnson and Silvia Rivera, two transgender women of color. Many also pivoted to online platforms, which proved safer than meeting clients in person and in some cases allowed workers to earn more money than they had pre-pandemic. “I know 10 or 15 trans people making over $10,000 a month on OnlyFans,” one organizer from the Sex Workers Outreach Project told the New York Times last May, “and I’ve never known more than one trans person making that much a month in full-service [sex work] or porn or anything.” These are aspects of the industry that the Catholic Church fails to engage with in its condemnations of sex work.

When Covid-19 lockdowns all but eliminated in-person sex work during the early months of 2020, sex workers in New York quickly organized housing relief and emergency funds for one another, carrying on a long tradition of mutual aid in the sex work community that goes back to Marsha P. Johnson and Silvia Rivera, two transgender women of color. Many also pivoted to online platforms, which proved safer than meeting clients in person and in some cases allowed workers to earn more money than they had pre-pandemic. “I know 10 or 15 trans people making over $10,000 a month on OnlyFans,” one organizer from the Sex Workers Outreach Project told the New York Times last May, “and I’ve never known more than one trans person making that much a month in full-service [sex work] or porn or anything.” These are aspects of the industry that the Catholic Church fails to engage with in its condemnations of sex work.

One thing is clear: To the extent that Catholic attitudes towards sex work – including the idea that sex workers are spiritually “dead” – reinforce prevailing stigmas, they put the Church in a position of contributing to, rather than alleviating, the pressures sex workers face.

Another generalization haunting Christian approaches to sex work is the idea that it is only a women’s issue. The Gospels speak frequently of Jesus’ ministry to female prostitutes, so ecclesial outreach to “fallen women” can claim a scriptural basis; but no similar template exists for male prostitutes. Recent estimates put the number of male sex workers worldwide just north of eight million, accounting for some 20% of the global sex worker population.

The male sources I spoke to for this article highlighted different concerns than their female counterparts. In Latin America and parts of Europe, for instance, men may engage in sex work as a way of supporting their families, who are often in a different country. On the other hand, prostitution is sometimes one of the only means for young men in more repressive social settings to act on their same-sex attraction. Pimps are far less frequently found among male sex workers, as are friendships with other sex workers. The threat of physical violence (at least from clients) is less acute than it is for women, and male sex workers tend to age out of the business more quickly than women.

These and other factors can give male sex workers a greater sense of independence, but also intensify feelings of isolation and internalized shame. One priest I spoke to who ministered to sex workers in the global south observed that while brothel women tended to operate more like a unionized workforce and – at best – a kind of sisterhood, the men were akin to independent contractors. These facts are sometimes reflected in the spiritual practices of male sex workers, which could involve near-total disaffiliation from institutional religion, or a turn to nontheistic, individualized spirituality.

For his much-discussed study of homosexuality at the Vatican, the French author Frédéric Martel spoke to many of the young male escorts and street prostitutes of Rome. Martel told me that of those he asked about their faith, most were Muslim but “none” of them seemed to have a strong religious practice, or they were at least able to compartmentalize their sex work from their religious identities (especially as long as they refused to bottom, a refusal which allowed them to excuse themselves, in their minds, from the supposed sin of homosexuality). He recalled one particularly devout young man – a Romanian Orthodox Christian – who seemed to have “two lives:” one with his wife and daughter back home and another on the streets of Rome. Whatever else one might say about the approaches these men took to their sex work, they belie something other than the purely passive state of victimization that typical Church narratives of sex work promote.

***

As long as Catholic approaches to sex work amount to a uniform “shame and rescue” model, they fail to speak to the full range of humans who engage in this work. More to the point, such an approach fails to give sex workers what they often need, regardless of their particular experience: namely, a measure of acceptance and recognition of their dignity that they are unlikely to find in the wider society.

The Church could be a natural stage for this kind of recognition, but this would require that it commit itself to integrating such people more fully into its common life of worship, prayer, and witness. It would require finding creative ways to reflect on their experiences while meeting their spiritual and material needs. Most of all it would require recognizing the hard-won spiritual wisdom that such individuals can bring with them.

***

It is telling that one of the iconographic details usually associated with Mary of Egypt is a meagre ration of bread, which she was said to have brought with her into the wilderness and lived off of for many years. Prostitutes and sex workers today are likewise forced to live off scraps for their spiritual sustenance. But like Mary, the individuals I spoke with did not starve—and like her, their example provokes questions about where we expect to find signs of grace today.

Travis LaCouter is a Visiting Assistant Professor at the College of the Holy Cross. His first book, Balthasar and Prayer, is out now with T&T Clark (Bloomsbury).