Sex, Scandals, and Buddhist Monks in Thailand

Numerous scandals are altering the lives of Thai Buddhist monks

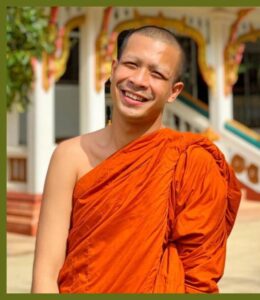

(Buddhist monks in Thailand. Image source: Getty Images)

In March 2022, Thailand was abuzz with the story of a leaked audio recording that revealed the clandestine love affair of a 23-year-old Buddhist monk and a 37-year-old model. Phra Ponsakorn Chankeo, or “Phra Kato” as he was known to his many devoted followers, was the young, charismatic acting abbot of Wat Pen Yat temple in southern Thailand. Phra Kato, who, like all monks, took a vow of celibacy, ended up being another source of disappointment for Thai Buddhists, whose religion has been rattled with scandals in recent decades.

Since his ordination in 2017, Phra Kato was considered a rising monastic star who could invigorate Buddhism through his skilled use of social media. His good looks and entertaining talks gained him a huge following on YouTube and Facebook. Many monks at the higher levels of Thailand’s monastic administration, concerned with the declined interest in and practice of Buddhism, thought they had found someone who could appeal to the younger generation and revitalize Buddhist practice.

But this all came crashing down with the release of the audio tape. Adding fuel to the fire, Phra Kato had embezzled 600,000 Thai baht (around $16,000 USD) from his temple, giving half to silence his lover and the other half to silence a reporter. The scandal played out on social media for weeks. Phra Kato and the infamous location of his multiple liaisons, in the backseat of his lover’s parked car on the crest of the Kathoon dam, became a tourist attraction and a popular meme. Phra Kato left monastic life in disgrace, returned the money to the temple, and was charged with embezzlement. He apologized to his fans and asked forgiveness through a video post on his YouTube and Facebook pages. Phra Kato, now Ponsakorn, parlayed his notoriety into becoming a social media influencer.

Phra Kato’s sex scandal rekindled memories of the father (pun intended) of all monastic scandals that engulfed Thailand in the 1990s: Phra Yantra Amaro. There is not a Thai who lived through the 1990s who does not know the story of the meteoric rise and fall of the charismatic Phra Yantra. Ordained in 1974, he was well-known as a disciplined monk who practiced asceticism and intense periods of meditation. He also had a reputation for possessing supernatural powers. In 1993, after returning from a world tour where he gave talks on Buddhist teachings, several women lodged accusations with the Thai monastic administration’s governing council saying that he had had sexual relations with them. One woman also claimed that he fathered her child. She demanded that Phra Yantra have a DNA test to prove he was the father, which he refused. In 1994, the Phra Yantra scandal was Thailand’s most widely reported news story, equivalent to America’s OJ Simpson trial. By 1995, there was incontrovertible evidence that Phra Yantra engaged in sexual relations. He had used a credit card to pay for his visits to brothels on trips to Australia and New Zealand. The governing council announced that he must disrobe for violating sangha (“Buddhist monastic community”) rules and for breaking his vow of celibacy.

These monks’ sexual affairs were so significant because violating the rule against sexual intercourse is one of the four most serious rules for Theravada monks. A monk who breaks one of these rules must disrobe and can never ordain again.

(Phra Kato. Image source: The Times)

Phra Kato’s and Phra Yantra’s scandals were far from the first or last to befall Buddhist monks in Thailand. On the evening of August 29, 2021, seven monks–four of them abbots–were caught drinking beer and feasting on roasted pork in the sacred chanting hall of Wat Phan Sao in Chiang Mai. Monks in Thailand are not allowed to eat after noon, and alcohol is strictly prohibited. The monks were arrested for breaking COVID-19 protocols and expelled from the sangha for breaking their sacred vows.

Newspapers in the 1990s were filled with stories of monastic scandals. There were countless reports of sexual misconduct, drinking, gambling, stealing from temple bank accounts, using and selling drugs, and even murder. Now, in the age of social media, these scandals are even more widely publicized. Each time another scandal goes public, Thai lay Buddhists question the role of monks in society as monks themselves consider their own relationship to the sangha.

Parallels to the mistrust of the Catholic priesthood in the United States are instructive. The widely reported pedophile priest scandal has resulted in fewer ordinations and more “priestless parishes.” The current birth rate in Thailand is 1.51 children per mother, even lower than China. Each year there will be fewer and fewer boys who will reach the age of ordination. Parents must decide if they want their son, and it is usually their only son, to pursue the monastic path. These scandals and their amplification through social media mean that having one’s son ordained as a monk is not as prestigious, or as safe, as it once was. Parents may hesitate to entrust the care of their sons to monks whose reputation may not be exemplary.

These scandals are a threat to the compact that binds laity and the sangha. The laity offer food, material goods, and money to temples and their monks. In turn, the laity receive “merit,” which in the Thai Buddhist view negates the effects of “bad karma” – or past unwholesome acts. Although merit can be gained by giving to charities, traditionally, the greatest amount of merit can be gained by giving to monks. The higher the receiving monk’s status, the more merit is generated. When monks are perceived to neglect their part in this reciprocal merit economy by disobeying their rules of renunciation, the merit system is compromised.

How, then, have these monastic scandals, especially the explosive Phra Kato one, affected the daily lives of ordinary young monks? We posed this question to monks living in Chiang Mai, a Buddhist academic center with several monastic high schools and two Buddhist universities.

One monk told us that when he left his temple one day to collect his morning alms, which is one of the signature daily morning rituals of Theravada Buddhism, a group of women pointed at him and yelled “Kato, Kato!” Laypeople, even friends, treated him as the butt of jokes. Friends on Facebook would comment or message him calling him ‘Kato.’ Another monk, while also collecting donations outside his temple, heard lay people jokingly inquiring about monastic activities, while referring to the location of Phra Kato’s affair: “Have you been to the dam today?” This kind of teasing suggests that people believe all monks have secret transgressions and are not following the rules of monastic discipline.

The scandals have created specific concerns about sexual misconduct and male monks interacting with women. According to the Vinaya, the rules that guide monastic behavior and appearance, monks should avoid close contact with women. Yet meditation teacher Phra Kyo told us that he often finds himself teaching in a room with only female students. Phra Kyo is concerned that some people might find it inappropriate for monks to be seen in a room with only women without understanding the context. Monastic life today is now more complicated because of the laity’s judgmental gaze.

Phra Kasem, who lives in a temple in a suburb of Chiang Mai, believes that scandals did not impact his community’s support for him because of their close personal relationship. However, the scandals still affect his monastic life because people have less faith in monks they do not personally know. On the occasions when Phra Kasem is invited to chant at ceremonies away from his temple, his supporters warn him to be careful. They remind him that Phra Kato traveled to other temples, and will say, “look what happened to him!” They worry about the temptation and suspicions monks face outside of familiar surroundings.

Articles about misbehaving monks are not only read by laity, but by monks as well. Monks also read the myriad online comments decrying the decline of monastic purity. Student monks reported to us that they believe the authors of these comments must be lay people who have not studied Buddhist teachings. Because they read only bad news about monks, the student monks presume, such lay people are beginning to lose their faith in Buddhism. They also surmise that lay people who have studied Buddhism will maintain their faith, confident that Buddhism is not affected by a few bad monks. Although monastic misbehavior is a widespread issue, when trying to explain the proliferation of scandals, these monks focus on the “few bad apples” phenomenon. They see monastic training as important, though not always effective, and that some men simply are not ready for the monastic life, which makes the whole institution appear tainted.

The training monks receive is not consistent from temple to temple, which has contributed to ongoing monastic problems. Monks learn about monastic life and proper behavior as part of their training as novices, or for a short period before their ordination ceremonies. It is up to the individual temples and abbots to make sure each ordained male knows how to follow the rules. However, with over 33,000 active temples and approximately 300,000 monks, monastic regulation is uneven.

(Thai Buddhist monks. Image source: Giulio Di Sturco for the International Herald Tribune)

Because of frequent scandals and the reaction of the laity, monks are concerned about the future generation’s support for Buddhism and, indeed, the future of Thai Buddhist practice. Phra Panya shared with us that he has seen very few young people visit his temple, reasoning that the scandals have alienated them. And Phra Ananda told us he thinks the “new generation” believe they can be good people without guidance from monks or the Buddha’s teachings.

Monks who live and study in Chiang Mai agreed that as more of these scandals become known, fewer people go to temples. They report less participation in temple activities after the Phra Kato scandal broke, though they acknowledge that the COVID-19 pandemic is another factor. Monks typically receive many invitations for them to offer blessing rituals for new houses, cars, or businesses. Lay people would come to temples for their birthdays, anniversaries of funerals, or for ceremonies to increase one’s longevity. But many of these requests have stopped. Lay temple patrons who would typically host a funeral ceremony for several days have now been shortened to one. Chiang Mai monks report that they have received fewer invitations for ceremonies and lower attendance at major Buddhist holidays. Fewer ceremonies result in a decrease in donations. And with less financial support from the laity, student monks must find other means to pay for tuition and other necessary expenses.

Phra Ajarn Dr. Phaitoon, a professor at MahaChulalongkornrajavidyalaya Buddhist University in Wang Noi, outside of Bangkok, said that the Phra Kato scandal has resulted in rarer ordinations of novices and fewer monastic students coming through the “pipeline.” Wat Srisoda, a temple in Chiang Mai, usually has more than 600 novices joining their temple school each year, but those numbers have reduced sharply. Last year there were only 50 novices. This appears to be a trend all over Chiang Mai: Wat Pa Pao had more than 40 monastics a few years ago but now has only 10. Over the last five years the number of monastics at Wat Som Phao has reduced by two-thirds.

With the plethora of news about misbehaving monks, there is little room in social media for positive stories about good monks. The problem is that positive stories, such as monks helping to build schools, or providing food for poor families, have no “legs.” These positive articles, appearing in social media, are read by the general public once, but scandals such as Phra Kato’s play out for weeks. Phra Kato’s strong but local media presence was quickly outweighed by the deluge of posts concerning his transgressions.

In July 2022, the new abbot of Wat Phan Sao held a panel discussion to reestablish the relationship between the monks and lay community. One woman brought up the issue of monastic scandals. The panelists focused on looking forward. It is natural, they said, that some monks will not be able to maintain the entirety of the renunciant’s lifestyle necessary to keep the monastic rules. Instead of feeling concerned, one panelist explained, laity should feel relieved. When scandals occur, those who are unable to maintain the monastic life are revealed, and only those who are pure will stay.

While the scandals have had a negative effect on male monks, they have had a positive effect on the small number of female monks, known as bhikkhunis. Monks (bhikkhu) are required to be celibate, forswear intoxicants, and follow the 227 behavioral rules of the Vinaya—the rules that govern behavior and appearance. In contrast, female monks (bhikkhunis) have 311 behavioral rules, and nuns (mae chi) follow eight precepts. There have been, as yet, no reports of bhikkunis or mae chi involved in sexual scandals. However, there are less than 300 bhikkhunis and around 30,000 mae chi in comparison with 300,000 bhikkhus.

Bhikkhunis are not allowed to ordain in Thailand. Instead, candidates travel to Sri Lanka for their novice training and ordination. Although their status as bhikkhuni is not accepted by the Thai sangha administration, they receive much support from lay people throughout Thailand who are aware of their dedicated practice. At the same time, many senior male monastics disapprove of bhikkhuni, believing that the Theravada lineage of bhikkhuni died out in the 11th century in Sri Lanka, and cannot be revived. Since there are fewer bhikkhuni and it takes great effort for them to ordain, they are, in general, committed to the proper practice of monasticism. Luang Mae Dhammananda, the first bhikkhuni in Thailand, feels that Thai Buddhists might be tiring of male monks and their scandals. She has observed an increasing number of supporters who only give alms to female monks and believes this could be attributed to their loss of trust for male monks.

The accumulated impact of these scandals is making Buddhism’s role in Thai society far more complicated. When monks are known to be in breach of their 227 rules there is less trust, more suspicion, and an increasingly fragile monastic-lay relationship. On the other hand, there are clear and prominent examples of dedicated and disciplined bhikkunis, who, although not uniformly accepted because they are women, point a way towards restoring Buddhism’s reputation in Thailand.

Brooke Schedneck is Assistant Professor of Religious Studies at Rhodes College, Memphis, Tennessee. She is the author of Religious Tourism in Northern Thailand: Encounters with Buddhist Monks, published by the University of Washington Press in 2021.

Steve Epstein is a visiting lecturer at the Chiang Mai campus of Mahachulalongkornrajavidyalaya Buddhist University in Thailand. He is the author of Lao Folktales, published by Silkworm Books.