Seeing Through Stained Glass: Gay, Catholic, and Conflicted

His father's funeral forced him to confront the Catholic community that once condemned him.

Walking into my hometown church for the first time in twenty years, a lump formed in my throat, my shoulders spasmed and my legs buckled under the weight of my sadness.

Walking into my hometown church for the first time in twenty years, a lump formed in my throat, my shoulders spasmed and my legs buckled under the weight of my sadness.

I hadn’t come back voluntarily; I was here for my father’s funeral. He’d been sick for ten years and I thought I’d be prepared for his death. Turns out I wasn’t ready to face it, especially in a place that once caused me so much pain.

My husband, Michael, clutched my arm. “O God, Our Help in Ages Past” blared on the organ. Louder still were the whispers playing in my head. Sinners. God will punish you with the plague. You will suffer. You will burn.

Moving toward our seat, my pent-up anxiety was subdued by the creaking sound of people shifting in their pews. Inexplicably, I’ve always loved hearing that noise.

Catching my breath, I opened a Bible and took in its aroma. Old and dusty, with a hint of pine, it smelled like my favorite bookstore. I was overcome with a sense of familiarity. But I also felt longing, regret, and trauma.

I looked at the stained glass windows for comfort, like I used to do when I felt uncomfortable at Sunday Mass. As a closeted gay teenager in a conservative Catholic family, that happened quite often. I stared at my favorite, an image of the Virgin Mary holding the Baby Jesus in what looked like a thousand shades of blue, and searched for answers. Like the window, my mind was a bit blurred.

I looked at the stained glass windows for comfort, like I used to do when I felt uncomfortable at Sunday Mass. As a closeted gay teenager in a conservative Catholic family, that happened quite often. I stared at my favorite, an image of the Virgin Mary holding the Baby Jesus in what looked like a thousand shades of blue, and searched for answers. Like the window, my mind was a bit blurred.

Before puberty, I loved going to church. As a kid growing up with leukemia, it was one of the few places I was allowed to visit outside of the hospital. And if you ask my Italian mother, it’s a toss-up as to which institution played a bigger role in saving my life.

When I was diagnosed with the illness at the age of four, it didn’t take long for the news to spread through our parish. People immediately started treating me differently. The seniors that loved pinching my cheeks now gave me a limp pat on the head. The nuns who scolded me for mixing up the words to the Our Father (I thought it was “Our Father who art in heaven, Halloween be your name”) now grinned at my mistakes.

I enjoyed being a part of a community, especially the prayer circles led by Father John, a soft-spoken priest in his mid-forties who always walked around barefoot. Yet hearing Father John say things like, “We pray, dear Lord, that you spare Mark’s life,” was unnerving. Though I was a young kid, his words made me understand the severity of my illness and the delicate balance between life and death. I was grateful to survive—until I became a teenager and found myself unexpectedly attracted to other boys.

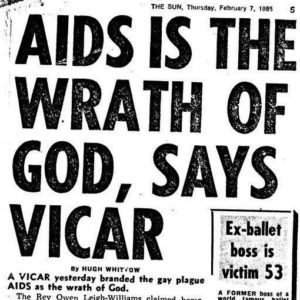

In our congregation, people talked about homosexuality like it was worse than adultery or murder. It was as if “Thou Shalt Not Be Gay” was the unwritten 11th commandment. The church ladies were the most outspokenly homophobic. I hated the way they gossiped about “men who acted like women” and wished they’d get the “gay cancer.” It was 1990 and the specter of AIDS was devastating. Nearly a million people were said to have the disease and I was terrified I’d get it too. At 13, I hadn’t even kissed anyone, but I was naïve and sheltered enough to believe I could contract AIDS just by thinking about having sex with other men.

I wanted to suppress my desires, but I struggled. Temptation was everywhere, from shirtless basketball players in gym class to the bronzed lifeguards in speedos at the beach. Desperate, I used my past illness as an excuse to get out of gym class and avoided the beach, pool parties, and other social activities that would spark impure thoughts. I mostly stayed home, praying to be “normal.”

Around the same time, my father had a near-death experience and decided to return to church. Since my siblings were older and had their own lives, I alone accompanied my parents to Mass. I was used to having this time with Mom, but I loved sharing it with my father. I’d always had trouble connecting with him. It didn’t help that he was a loud, stubborn, and sometimes scary construction worker, while I liked reading romance novels and couldn’t hit a baseball. Yet now we had something we could do together. When Father John asked me to do the weekly readings, Dad beamed. I’d never seen my father so proud.

As soon as I stood at the altar, though, I trembled with fear. I tried to keep my focus on the Gospel of Matthew or whatever Father John had chosen, but I envisioned everyone pointing at me, whispering at me. We know what you are. Your family should be ashamed. You will burn. Fumbling with my words, I turned to Mary and Jesus bathed in blue in the stained glass window and kept trying.

I got through the readings but, despite my best efforts, I couldn’t change my sexuality. At my Confirmation ceremony, I was more focused on what my male classmates looked like under their robes than accepting the Holy Spirit.

The next day, I went to confession and finally divulged what I was. I trusted Father John. This was a man who’d prayed to save my life, surely he’d want to help me save my soul.

“If you act on these feelings, you will get AIDS and suffer in Hell,” he said.

“If you act on these feelings, you will get AIDS and suffer in Hell,” he said.

I froze, speechless and even more frightened. Father John was someone I trusted, who’d prayed for my life, so I believed him. The threat of going to Hell for being gay felt even more real.

“Is there anything else?” he asked, dismissively. I wished I hadn’t said anything. Though it was supposed to be confidential, I worried Father John would tell my parents. The fear that they’d disown me was as panic-inducing as the thought of eternal suffering. I was so desperate to spend time with my father and didn’t want to lose that. I forged on, Father John and I both pretending as if I’d never confessed, but the façade could only last so long.

Just after my 16th birthday, I went on a church-sponsored retreat at a campsite in upstate New York. We broke off into smaller groups of four—and then it was just me and another boy. Alone, we talked, dared, and eventually touched.

Though his hand caressed my leg before I’d made a move, he called me a faggot, then told everyone what I’d done. The rumblings spread through the camp, over the Adirondacks and to the church. Father John called a meeting with my parents, and he didn’t arrive alone. Seven concerned parishioners filled the room. My Judas stood behind them, along with his mother and father. His mother led the charge, her smoker’s voice crackling at me with disgust. They all agreed I was no longer welcome at church.

I was heartbroken that a community I’d loved deeply would disown me like this. Too wounded to fight back, I absorbed their venom. All of the compassion and kindness I’d experienced as a child faded away. At that moment, I knew their love would always be conditional. I’d spent years sacrificing my happiness and self-worth, but I was tired of suppressing my sexuality. I needed to accept that I was gay, not be condemned for it.

To my surprise, my parents took my side. Mom pulled no punches, lashing out at a “group of hypocrites” who’d been divorced or engaged in extramarital affairs. At home, there was no epic coming out speech or further talk of acceptance. We wouldn’t speak about my sexuality again for years. My parents still went to church, which made me feel betrayed. Regrettably, I never had the strength to ask them why.

As much as these experiences traumatized me, I missed being a part of the community. I tried to fill the void by experimenting with Buddhism and Judaism, but both felt forced and not something I could be committed to.

As the years went by and social attitudes changed, Dad encouraged me to go back to church with him. Father John was gone, the church ladies had died. I could light a candle or say a prayer without anyone knowing my identity. I fought him on it and leaned toward becoming an atheist, which Dad took worse than when I officially came out as gay.

“You’ve got more Christian goodness in you than anyone I know,” he’d persist. “You can’t just give up.” When I refused to listen, Dad emailed me Bible passages. His favorite was Jeremiah 29:11. “For I know the plans I have for you,” declares the Lord, “plans to prosper you and not to harm you, plans to give you hope and a future.” I deleted it multiple times.

Now, at Dad’s funeral, he’d finally gotten his wish and brought me back to Sacred Heart. It made me laugh, if only for a second. The priest called me up to deliver Dad’s eulogy. “Keep it short,” he whispered. My instinct was to listen, to obey like always. But this time I wasn’t afraid to fight back and speak up for myself. I rambled about how my father and I learned to love each other for who we were. I spoke about how he openly celebrated my marriage to another man.

It was freeing to be so uncensored in a place where I’d spent so much time suppressing my identity. This moment was supposed to be about honoring my father, but it became his last gift to me. As I ended his eulogy, I looked toward my favorite stained glass window. For the first time, I saw beyond the blurred lines and found self-acceptance.

Mark Jason Williams is an award-winning playwright, essayist, and travel writer. His work has also appeared in the Washington Post, Salon, Out, Rachael Ray In Season, Good Housekeeping, Far & Wide, Denver Post and more. He has a BFA in Dramatic Writing from NYU’s Tisch School of the Arts and is currently working on a memoir about surviving cancer and achieving his lifelong dream of visiting all seven continents.