Searching for God, One Bestseller at a Time

A conversation with Stephen Prothero about his book “God the Bestseller” and the pioneering editor behind some of the 20th century’s biggest books about religion

(Photo by Renee Fisher for Unsplash)

Eugene Exman did things before they became the thing to do. He traveled to Alabama to watch a young Reverend Martin Luther King, Jr. catalyze the civil rights movement. He founded a California commune with Aldous Huxley and searched for a guru in India long before The Beatles met the Maharishi. His experiments with LSD preceded Timothy Leary’s acid evangelism by several years.

For all of this, Exman might be mistaken for a trend-spotting but insignificant Zelig, an indistinct figure in the background, photobombing the spiritual elite. But he wasn’t just collecting experiences; he was recruiting authors for a religious mission: to redeem a world reeling from war and surrendering to the seductions of materialism.

The Ohio-born editor led the religious books department at Harper & Brothers, now known as HarperOne, from 1928-1965, where he published a who’s who of mid-twentieth century religion: King, Dorothy Day, Huxley, Howard Thurman, Albert Schweitzer, AA founder Bill Wilson, Zen Buddhist scholar D.T. Suzuki, and Jiddu Krishnamurti, among many others. His line of religious paperbacks introduced Americans to the works of Friedrich Schleiermacher, Abraham Joshua Heschel, Mircea Eliade, and Swami Prabhavanada.

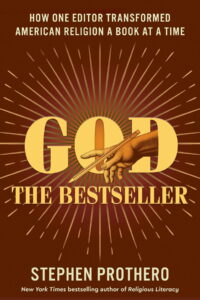

Exman was “the undisputed standard-bearer for religion publishing in the United States,” writes Stephen Prothero, author of a new biography and cultural history called God the Bestseller: How One Editor Transformed American Religion a Book at a Time.

Though the topics and traditions explored in Exman’s books varied, they were bound by a common idea: the personal search for divine connection, wherever it may be found, is the most essential element of religion. By publishing the autobiographies of seekers, mystics, and would-be saints, he offered paths of holy living that circumvented congregations and creeds. In doing so, Prothero argues, Exman cleared a way for the “spiritual, but not religious” contingent, an identity now claimed by more than a quarter of American adults.

Though the topics and traditions explored in Exman’s books varied, they were bound by a common idea: the personal search for divine connection, wherever it may be found, is the most essential element of religion. By publishing the autobiographies of seekers, mystics, and would-be saints, he offered paths of holy living that circumvented congregations and creeds. In doing so, Prothero argues, Exman cleared a way for the “spiritual, but not religious” contingent, an identity now claimed by more than a quarter of American adults.

I spoke to Prothero, a professor of American religion at Boston University and author of a dozen books, about why Exman placed “stepping stones across the stream of American consciousness from Protestantism to pluralism, from dogma to experience, and from institutional religion to personal spirituality.”

This interview has been edited and condensed.

Daniel Burke: What kinds of religious books were typically published before Exman came on the scene at Harper & Brothers in 1928?

Steven Prothero: It was mainly Protestant and denominational: a Methodist minister, writing a book of sermons that would be titled “Methodist” in some way and sold to Methodists. Exman’s idea was that clerics have interesting things to say to wider audiences. It was a broadening out to talking about faith and experience and what we would now call spirituality. That was the key shift. Over the course of his life, it keeps getting broader. He started to publish Buddhists, Hindus, Jews, and Catholics.

DB: What was he trying to accomplish through this broadening?

SP: His mission was to defend religion against its secular critics and to bring general audiences the best thinkers and actors on religion of the mid-twentieth century in order to save the world. He lived through World War I, the Great Depression, and then World War II. It was a tumultuous period when the belief in progress and in God were challenged by these horrific events – not least, the Holocaust. And it led many people to a search for meaning. Exman was very much a part of that, but he was convinced that meaning was to be found in God. He wanted to discover the best techniques for encountering God. He believed that if he discovered those techniques and published them, people would encounter God and stop fighting with one another.

Exman wanted to make the world more peaceful and just, and he believed you could do that by publishing books. And he’s publishing them at a time when books have huge cultural influence. They weren’t competing with the Internet, podcasts, or even television for much of his career.

DB: You describe a mystical experience Exman had as a teenager. How much of his view of religion as essentially experiential comes out of that episode?

SP: Almost all of it. Exman, who grew up in a fundamentalist church, tried to be converted at revivals when he was a kid, but he didn’t have any kind of conversion experience. But one day, as a teenager, he was riding his horse to a Bible study when suddenly his horse rears up and Exman looks up and sees and feels God, and he never doubted God’s existence again.

There are, of course, antecedents to this idea of religion as experiential. Schleiermacher, the German theologian, writes about religion as experience. There were the First and Second Great Awakenings in the United States. Transcendentalists, who thought that religion is not about sitting in church, but about getting out in nature and finding God there.

DB: And Exman spends the rest of his life trying to recapture his teenage experience, studying ways to connect with the divine and publishing books about people who have done so?

SP: Exactly. He just wants to see God again. It’s like, if the first time you went to a Red Sox game, you caught a foul ball, and then you keep going to baseball games, hoping that will happen again. And it never does for him.

DB: It sounds like the opposite of Alan Watt’s adage about psychedelics that “if you get the message, hang up the phone.”

SP: Exactly. He never hangs up the phone. He just keeps calling. And he’s also calling his friends and asking, “What number did you use when you were able to dial into God? Can you share it with me?”

DB: You make the argument that Exman helped spread the “religion of experience,” which you suggest is the most popular religion in contemporary America. How do you define it?

SP: It’s best understood through the eyes of William James, who was a huge influence on Exman. For James, religion is not fundamentally about ritual, it’s not fundamentally about doctrine. It’s about feeling and experience, and the highest experience is the encounter with God. So it’s personal, rather than collective. Institutions just get in the way. What Exman does is spread that idea in ways that make sense to people who aren’t Harvard philosophers and psychologists. I see him as a middlebrow popularizer of the “religion of experience,” and through the books he puts out into the world, it becomes very popular. And this is not just an idea of the left. I would suspect that the religion of experience is largely the religion of most white evangelicals in the United States, maybe even the white Christian nationalist insurrectionists of January 6.

DB: I’ve been thinking about the “religion of experience,” as you call it in the book, and how common it is. For instance, experience is primary in Zen Buddhism. You see it in Hinduism and Islam as well, with darshan and the Hajj. So I wonder whether the rise of the “religion of experience” is just a reversion to the norm?

SP: That’s a good question. I do think the perceived wrong guys for people like Exman are the “doctrine of religion” people who believe that what makes you Christian is believing A, B, and C. As you say, that’s weird in world religion terms, right? But as you mentioned darshan and the Hajj, I was thinking: Do those count as “the religion of experience”? I think darshan would, but I’m not sure about the Hajj, which might be too corporate – too big and busy. Exman would say that you could find moments of contemplation in the Hajj, and that would be the religion of experience. A lot of the other parts of the Hajj would be the religion of busyness. The religion of experience has a whiff of contemplative practice, of Jewish theologian Martin Buber’s I and Thou: the encounter of the self with the mysterious divine, and cultivating the techniques that help you have that experience.

But Exman’s interest in mysticism and religious experience wasn’t escapism. He believed that to encounter God is to be compelled to act compassionately in the world. He wasn’t spending all of his time contemplating the reality of the universe.

DB: Exman had a pluralistic view of religion, but he also had areas of ignorance on religion and race, as you note. A co-editor tried to get Dorothy Day to write less about St. Therese of Lisieux and Exman encouraged Martin Luther King, Jr. to end his first book on an optimistic note about racial assimilation.

SP: Exman and the people in his religious books department at Harper & Brothers were overwhelmingly white, liberal Protestants. They were trying to be political progressives and religious pluralists. They thought there was truth in all religions, but at the same time they were not always aware of their own biases.

When it comes to race, Ibram X. Kendi, my colleague at Boston University, is helpful in making a distinction between well-meaning white liberal assimilationists and anti-racists. Exman certainly wasn’t an anti-racist. As King was writing his books, Exman was telling him, “let’s bring the races together. Let’s make it all happy.” And King was trying to bring the races together, but he was also keenly aware of white supremacy and the power of racism. He was getting death threats daily.

And so when Exman encouraged King to write a happy ending to his account of the Montgomery Bus Boycott in “Stride Toward Freedom,” King did almost exactly the opposite. He ends with this beautiful, prophetic biblical blast, warning that the world might come to an end if we don’t do something about violence and racial injustice.

Daniel Burke is director of communications at Georgetown University’s Center on Faith and Justice. Formerly CNN’s religion editor, he is writing a book about religion, revelations, and mental health.

Stephen Prothero is a Professor of Religion at Boston University specializing in American religions. Prothero has written six books. His two most recent projects are The New York Times bestseller Religious Literacy: What Every American Needs to Know–and Doesn’t and God is Not One: The Eight Rival Religions that Run the World and Why Their Differences Matter.