Sacrificing Healthcare Workers: War Rhetoric and the Coronavirus Pandemic

Why do we expect healthcare workers to sacrifice themselves for the sake of the nation?

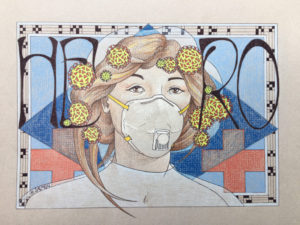

In San Jose, a local artist recently designed a picket fence mural to honor healthcare workers. The mural features doctors in lab coats with stethoscopes draped across their shoulders. Personal protective equipment covers the lower halves of their faces. In bold white lettering the famous Winston Churchill quote, “never was so much owed by so many to so few,” gleams next to traditional symbols of healthcare. The mural juxtaposes medicine and the rhetoric of a wartime speech, reflecting the shape of a national conversation about health during the coronavirus pandemic in the United States.

In San Jose, a local artist recently designed a picket fence mural to honor healthcare workers. The mural features doctors in lab coats with stethoscopes draped across their shoulders. Personal protective equipment covers the lower halves of their faces. In bold white lettering the famous Winston Churchill quote, “never was so much owed by so many to so few,” gleams next to traditional symbols of healthcare. The mural juxtaposes medicine and the rhetoric of a wartime speech, reflecting the shape of a national conversation about health during the coronavirus pandemic in the United States.

Public demonstrations of gratitude toward healthcare workers are especially visible now. Rituals of giving thanks, largely organized on social media, are spreading across the globe. In France, Italy, and Spain, nonessential workers and people outside of the labor force, asked by their governments to remain indoors, stand on balconies cheering and applauding healthcare workers. Businesses ranging from local catering companies in the United States to international petroleum corporations offer discounts, free products, and services to healthcare workers and first responders battling on the “front lines.” On March 29, Google posted a video noting trending searches for how to help healthcare workers, advising people to do their part by staying home, and thanking healthcare workers: “to everyone sacrificing so much to save so many, thank you.”

As March blended into April, military metaphors became the primary way we imagined healthcare workers. Commentators in the media, government agencies, and the general public insist that doctors, nurses, and other hospital staff are soldiers stationed at the front lines. They wage war against the coronavirus. They are our first and perhaps only line of defense.

Wartime metaphors have also been used to emphasize the dire situation in hospitals. Medical doctor Laura Kolbe reports “from the frontlines” that corporate and political responses seem less worried than hospital staff are with “the situation on the ground,” remarking: “If you have enough infantry, you can countenance a good deal of loss. Operations can continue even if many are out sick.” The imagery and her insights are chilling. In the war against the novel coronavirus, we are throwing as many bodies of healthcare workers as we can marshal against this pandemic.

Equating healthcare workers with soldiers through the metaphorical language of war obscures the complexity of our current moment, suggesting that a particularly virtuous group of heroic individuals can save us from destruction—and that many may have to sacrifice themselves to keep the rest of us alive. But demanding that healthcare workers embody an ideal form of courage, determination, and self-sacrifice reduces the complicated choices healthcare workers face to a simple story of suffering, sacrifice, and national salvation.

***

Jonathan Ebel, a scholar of religion and a U.S. Navy veteran, persuasively traced the interconnectedness between religion and the images (and actual lives) of soldiers in his book G.I. Messiahs: Soldiering, War, and American Civil Religion. In this book, Ebel studies soldiering as a civil religious practice, the “things soldiers do, are asked to do, expected to do, and are portrayed doing to embody devotion to the nation.” Ebel argues that American civil religion—a network of symbols, ceremonies, political speech, and national myths—is shaped by Christian incarnation theology, particularly evident when the bodies of American soldiers become “the word of the nation made flesh” through suffering and self-sacrifice. Christianity provides the nation with the symbols, stories, and language to acknowledge the service of soldiers, celebrate their lives, and mourn their deaths. The soldier-savior trope is persuasive and emotionally forceful because soldiers have literally served the nation, suffered profoundly, and often sacrificed their lives. Yet, Ebel continually reminds his reader that soldiers are people who often struggle with the “burdens of civil religious incarnation” because of “what the nation has asked them to do and because of the ideal that they and others imagine themselves to embody.” He points out that “symbolizing processes” have “no interest in tensions or complexity within the symbolized.” This means that the U.S. soldier, as a symbol, represents for us the virtues of courage, strength, and devotion to the country, while erasing the particularities and personalities of real people.

Medical professionals, not unlike soldiers, are also called upon to embody an ideal. My wife works in healthcare, which means I have personally observed and admired the commitment it requires to wake up early in the morning and work long, arduous hours in a high-stress, life and death environment. She and her colleagues, our friends, often spend their holidays away from loved ones. They have their sleep interrupted by pager alerts and phone calls. They restart stopped hearts. They show whatever kindness they can to grieving families who have lost a parent, sibling, or child. It is little wonder that medicine is often described as a “vocation,” an originally religious term that implies one has been “called,” indeed created, for a particular task.

Medical professionals, not unlike soldiers, are also called upon to embody an ideal. My wife works in healthcare, which means I have personally observed and admired the commitment it requires to wake up early in the morning and work long, arduous hours in a high-stress, life and death environment. She and her colleagues, our friends, often spend their holidays away from loved ones. They have their sleep interrupted by pager alerts and phone calls. They restart stopped hearts. They show whatever kindness they can to grieving families who have lost a parent, sibling, or child. It is little wonder that medicine is often described as a “vocation,” an originally religious term that implies one has been “called,” indeed created, for a particular task.

Healthcare workers, like soldiers, are a complicated and diverse group of people. Soldiers enlist for many reasons—a sense of duty, a path to college, a steady job. Soldiers’ experiences in the military vary greatly. Some feel that their service was meaningful, others deal with post-traumatic stress or feelings of betrayal. Similarly, healthcare workers do not all become doctors or nurses or techs because they want to work in critical, life or death cases, to practice emergency medicine. Some nurses see caring for those in need as a higher purpose where others see a career with reasonable healthcare and retirement benefits.

While people all over the world thank medical professionals for their necessary work during this pandemic, it is crucial to remember that many providers feel ambivalent about putting their own lives and the lives of their patients at risk by working without adequate protection. Some hospital staff are angry that administrators are not doing enough to support them. Administrators at Detroit Mercy Center Sinai-Grace asked a group of emergency care workers to leave the hospital after they protested working conditions. Staff at Sinai-Grace are caring for up to twenty patients at a time and expected to wear the same personal protective equipment for twenty-four hours. Under normal conditions, intensive care workers provide one-to-one care for seriously ill patients, not twenty-to-one. Under normal conditions, protective equipment is disposed of after each interaction to prevent cross-contamination between patients and to protect healthcare workers.

The hospital’s response is telling: “We are disappointed that last night a very small number of nurses at Sinai-Grace Hospital staged a work stoppage in the hospital refusing to care for patients. Despite this, our patients continued to receive the care they needed as other dedicated nurses stepped in to provide care.” Rather than acknowledging the hazardous working conditions and shortages that nurses and other hospital staff face, the hospital administration singles out this group of care workers as disappointing and contrasts them to the more dedicated and devoted staff. One group embodies the ideal, demonstrating their devotion through suffering and sacrifice. Outspoken employees do not.

It is safe to assume that many healthcare workers around the country are wrestling with concerns resembling those expressed by the Sinai-Grace staff. In a time when hospitals are actively silencing their staff and terminating physicians and nurses who post on social media or give interviews to news networks about conditions at hospitals, those people who continue to provide care despite inadequate resources or relief must be asking themselves: do I speak out and risk losing my job? What if I get sick and bring the virus home to my family? Is this all worth dying for? If I am gone, or ill, who will care for my children or elderly parents? Can I care for my patients and my family?

It is safe to assume that many healthcare workers around the country are wrestling with concerns resembling those expressed by the Sinai-Grace staff. In a time when hospitals are actively silencing their staff and terminating physicians and nurses who post on social media or give interviews to news networks about conditions at hospitals, those people who continue to provide care despite inadequate resources or relief must be asking themselves: do I speak out and risk losing my job? What if I get sick and bring the virus home to my family? Is this all worth dying for? If I am gone, or ill, who will care for my children or elderly parents? Can I care for my patients and my family?

Not everyone can live up to the heroic ideals of service, suffering, and self-sacrifice that our nation demands. Jonathan Ebel reminds us how the public reacts when a soldier does not adhere to the savior model by recounting the military career of Francis Gary Powers. Powers was a U.S. pilot taken prisoner by the Soviet Union in 1960 during a spying mission on behalf of the CIA. In the aftermath of Powers’ trial in Russia, an editorial ran in the Los Angeles Times condemning Powers for failing to put his nation before his own life: “He was at no time a man to choose death before dishonor.” Critics of Powers targeted his conduct—getting shot down, failing to destroy the spy plane and equipment, failing to destroy himself—and argued that these demonstrated the “flaws in his true nature and confusion in his true loyalties.” We’ve already seen an example of this same logic in healthcare, where the loyalty of nurses and doctors to their vocation, their hospitals, or those under their care is called into question. “Dedicated” or “devoted” staff are distinguished from those who presumably have questionable character because they fail to perform their duties no matter the conditions, demonstrate concern for their own well-being, or refuse to look past the breakdowns in hospital administration and national healthcare infrastructures.

***

Military metaphors have long been a part of healthcare in the United States, especially prominent after American battlefield victories in World War II. We draw associations between illness and war. Patients fight off viral infections. People and their physicians battle cancer. HIV assaults our bodies’ defenses. HIV researchers even borrowed George Bush’s famous phrase “shock and awe” to frame HIV cure strategies as “shock and kill.” Metaphors are an important feature of language because they shape how we understand our world and ourselves.

Returning to the mural in San Jose, its quote, and its tribute to healthcare workers might demonstrate the kind of comfort that war metaphors can bring to the people that use and encounter them. Wars can be won, and treaties can be negotiated. We would do well to remember that Churchill’s speech, delivered to the House of Commons on August 20th, 1940, addressed a nation gripped in the existential threat of total war. The expanded lines from his speech read: “The gratitude of every home in our Island, in our Empire, and indeed throughout the world, except in the abodes of the guilty, goes out to the British airmen, who undaunted by odds, unwearied in their constant challenge and mortal danger, are turning the tide of the world war by their prowess and by their devotion. Never in the field of human conflict was so much owed by so many to so few.” The abridged version of the quote on the mural omits the field of human conflict, the battlefield, the warzone, the nation mobilized for war. Churchill identifies heroic characteristics of the British airmen, suggesting that their devotion, skill, and courage are “turning the tide” of the war.

How might we expect healthcare workers caring for patients with coronavirus to “turn this tide”? What victory can hospital staff achieve? Will individual heroism save us? Is there any alternative to thinking about working during the pandemic other than fighting, suffering, and sacrificing? What do we risk by making heroes out of healthcare workers? Benjamin Morrison, a resident physician in New York, wrote in a letter to the editor of the New York Times that “medical staff are being forced to work in extremely unsafe conditions.” He reminds us that the “burden of care often falls on the lowest ranked workers,” and reflects, “We will be called ‘heroes’ to hide the truth: we were killed on dangerous job sites.” By resisting the urge to frame work in a hospital as battle on the front lines, Morrison redirects our attention to the precarity so many American workers face even in the best of times. This framing reminds us that risk is never shared evenly by all citizens. The grave situation facing healthcare workers is difficult to quantify at present, but estimates suggest up to 20% of Covid-19 infections in the U.S. are among hospital staff. Some of us are always more vulnerable than others, whether by choice or circumstance. Imagining a hospital as a dangerous workplace also makes it possible to imagine that it could be less dangerous if staff received the proper protective equipment, training, support, and life-saving supplies. Wartime rhetoric makes the cause of injury or death for workers a foreign enemy on a distant battlefield, rather than an indication of the failures of management, markets, or government policies.

How might we expect healthcare workers caring for patients with coronavirus to “turn this tide”? What victory can hospital staff achieve? Will individual heroism save us? Is there any alternative to thinking about working during the pandemic other than fighting, suffering, and sacrificing? What do we risk by making heroes out of healthcare workers? Benjamin Morrison, a resident physician in New York, wrote in a letter to the editor of the New York Times that “medical staff are being forced to work in extremely unsafe conditions.” He reminds us that the “burden of care often falls on the lowest ranked workers,” and reflects, “We will be called ‘heroes’ to hide the truth: we were killed on dangerous job sites.” By resisting the urge to frame work in a hospital as battle on the front lines, Morrison redirects our attention to the precarity so many American workers face even in the best of times. This framing reminds us that risk is never shared evenly by all citizens. The grave situation facing healthcare workers is difficult to quantify at present, but estimates suggest up to 20% of Covid-19 infections in the U.S. are among hospital staff. Some of us are always more vulnerable than others, whether by choice or circumstance. Imagining a hospital as a dangerous workplace also makes it possible to imagine that it could be less dangerous if staff received the proper protective equipment, training, support, and life-saving supplies. Wartime rhetoric makes the cause of injury or death for workers a foreign enemy on a distant battlefield, rather than an indication of the failures of management, markets, or government policies.

It is impossible to predict what Covid-19 will cost the United States. It is highly likely that those costs will be steep and that the sacrificial emphasis we place on the heroism of individuals who are doing remarkable work will inevitably obscure our view of the full costs of this crisis. Military metaphors fail to capture the gravity of the choices facing essential workers, not just healthcare professionals, because we conceive of our soldiers as volunteers. We have a voluntary, professional military. This is why, when a soldier dies abroad, we often say “they signed up for it.” Equating essential workers with soldiers carries over this “voluntary” attitude toward soldiering in the United States. Healthcare workers, post office workers, and grocery clerks all “signed up” for their jobs. As those of us fortunate enough to work from home adjust to new schedules and choreographies in our daily lives, many are facing tough choices. The tough choices are epitomized by the words of a 63-year-old fitting-room attendant at Walmart: “How can I afford to live?” She is high-risk. Her family has begged her to quit her job for her own health. She cannot. For so many in the United States, the only answer to that question is to continue working in dangerous conditions. As our nation turns to wartime rhetoric, our focus should shift from sacrifice to the social infrastructures, government policies, and business decision-making that leave so many in such a precarious position that the question “how can I afford to live” is even conceivable.

Dale Spicer is a Ph.D. Candidate in the Department of Religious Studies at Indiana University. His current research and writing explore interconnections between religion, law, and medicine.