Rethinking Religious Violence

Kali Handelman interviews Darryl Li about his book The Universal Enemy: Jihad, Empire, and the Challenge of Solidarity

What is religious violence? What is jihad? Is jihad a useful way of understanding either religion or violence?

What is religious violence? What is jihad? Is jihad a useful way of understanding either religion or violence?

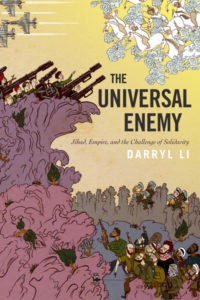

As both an anthropologist and a lawyer, Darryl Li is able to offer rare insights into — and critiques of — these questions by focusing on the lives of real people. Published after more than a decade of research in a half-dozen countries and multiple languages, Li’s new book, The Universal Enemy: Jihad, Empire, and the Challenge of Solidarity (Stanford University Press, 2020), is an account of two competing forms of universalism — Islamist jihad and American empire — in the Balkans during the years following the Cold War. Asking questions about religion, violence, and politics, The Universal Enemy is a model of the best kind of anthropology of religion — work that is ethically and theoretically rigorous, innovative, and uncompromising. Li’s study is not just a sensitive and sharp portrayal of his subjects, it is an urgently useful example of how future anthropological work ought to be undertaken. I was honored that he was able to take time over the last few months to discuss the book with me and that I can share our conversation with you here.

Kali Handelman: I’d like to start out by asking you to tell us a bit about how you came to write this book. But I thought I might ask you to focus particularly on the role of religion in this work. You are not a scholar of religious studies, per se, so I wonder what questions you had taking on a project that necessarily entails thinking about religion? What did you want to avoid? What did you especially want to accomplish?

Darryl Li: When I first embarked on this research 15 years ago, I was frustrated at debates that either treated religion — or, let’s be real, Islam — as the problem, or which tried to tell us that jihad was really a manifestation of some other problem like globalization. In other words, there was this unappealing choice between reductionism or dismissal when it came to religion. As someone who grew up neither embracing nor rebelling against religious traditions, I felt liberated from a lot of the anxieties that marked these discussions. The whole “how does religion explain violence?” question never interested me since both violence and religion are themselves incredibly broad concepts.

Darryl Li: When I first embarked on this research 15 years ago, I was frustrated at debates that either treated religion — or, let’s be real, Islam — as the problem, or which tried to tell us that jihad was really a manifestation of some other problem like globalization. In other words, there was this unappealing choice between reductionism or dismissal when it came to religion. As someone who grew up neither embracing nor rebelling against religious traditions, I felt liberated from a lot of the anxieties that marked these discussions. The whole “how does religion explain violence?” question never interested me since both violence and religion are themselves incredibly broad concepts.

Looking at contemporary jihad practices and the people engaged in them (mujahids), the ones that were most interesting to me — and which have attracted the most notoriety — have been those mobilizing volunteers from many different countries, so-called foreign fighters. These included mujahids who traveled to Afghanistan to confront the Soviet Union or outfits like al-Qa‘ida that lack a specific territorial locus but instead sought to attack the United States wherever they could. These jihads are striking precisely because of how they bring together violence, piety, and transnational mobility, thus upending the widely-held assumption that the only legitimate warfare is that waged by nation-states.

KH: Right, exactly. In the book you argue that texts cannot, in and of themselves, make people violent. In religious studies, we’re pretty used to making this point — that religious ideas and texts do not make people do things — religious texts do not, in and of themselves, produce something called religious violence. And yet, we recognize the need for serious conversations about the relationship between politics, religion, and violence. And that’s the kind of conversation about jihad that you bring your readers into. Crucially, you refuse to define “jihad,” and instead insist that the focus ought to be on how the concept of jihad is used to organize and justify political violence so that we can “ground concepts of Islam and violence in relation to one another without reductively shackling them together.”

DL: The framing I mentioned above — jihad qua transnational non-state armed campaigns — brackets out a lot of other things that get called jihad. It excludes violence by states (perhaps the most important yet understudied form of contemporary jihad), non-state groups seeking to overthrow ruling regimes or repel foreign occupiers, as well as unaffiliated individuals who “self-radicalize.” It excludes all the usages of the word “jihad” for non-violent or inner spiritual struggles. In fact, this sheer diversity is why speaking of jihadism doesn’t make sense to me, since it inevitably involves elevating some believers’ uses of the term “jihad” into a paradigm while marginalizing others, without articulating a convincing rationale.

The way I’ve just categorized my focus on certain types of jihad doesn’t correspond neatly to any particular category within Islamic law. But Islamic discourses and practices are still very important for the analysis. At the same time, mujahids live and operate in a world structured by the category of sovereignty, and their debates over doctrine are also shaped by it. I’m interested in how a doctrinal category (jihad) developed by and for believers confronts a political logic (sovereignty) that is shared by believers and non-believers alike. And this raises issues that have largely gone undertheorized in the voluminous commentary on jihad: how do we reconcile pan-Islamic commitments with doctrinal, racial, cultural, and other forms of difference in concrete settings of organized violence? The fourth chapter of the book highlights how the mujahids invoked a variety of Islamic notions of virtue, kinship, and community to process these differences and ground different forms of dispute and debate while enacting a project of armed solidarity. This gave me a way to take “religion” seriously without situating it as the cause or locus of violence.

KH: Similarly, I wonder what you think of efforts to expand, rather than minimize or eliminate, the use of “terrorism” to define acts of political violence? It’s a two-pronged project, right? First, to expose the way that “terrorism” is used to differentiate legitimate versus illegitimate violence in ways that are undeniably anti-Muslim and racist. And second, to apply the label to violence committed, for instance, by white supremacists. I understand the motivation, but I’m unconvinced that making “terrorism” apply more broadly solves the problem. Are there changes you would like to see in conversations about “terrorism”? And are there important differences between how this conversation plays out in the legal field versus in anthropology?

DL: I share your skepticism about the need or even possibility of using “terrorism” — at least in any of its recognized institutional forms — as a framework to combat white supremacy, especially when we are talking about the United States. Remember the 1995 Oklahoma City bombing? The deadliest act of terrorism on U.S. soil up until that point was carried out by white militia members. Yet the bipartisan governmental response was to pass a raft of laws significantly amplifying state violence against non-white populations: streamlining the death penalty, expanding the immigration detention and deportation regime, criminalizing broad swaths of charitable activity and political activism.

I think of “terrorism” as a political misnomer — it’s a refusal to name certain forms of violence as political, but the very act of non-naming is itself political and an implicit recognition that the violence in question is political as well. “Terrorism” is also a misnomer in the sense that it often marks certain groups but only in a coded way. So in the U.S. context, the need to qualify terrorism as “domestic,” “right wing,” or “white supremacist” reinforces the unstated assumption that the default terrorist is Muslim.

I think of “terrorism” as a political misnomer — it’s a refusal to name certain forms of violence as political, but the very act of non-naming is itself political and an implicit recognition that the violence in question is political as well. “Terrorism” is also a misnomer in the sense that it often marks certain groups but only in a coded way. So in the U.S. context, the need to qualify terrorism as “domestic,” “right wing,” or “white supremacist” reinforces the unstated assumption that the default terrorist is Muslim.

Most importantly, the terrorism framework is about reinforcing the state’s right to choose enemies while at the same time letting it off the hook for naming the politics of those alleged enemies. Sometimes this distorts or erases political claims that may otherwise be worthy of more serious consideration, as when al-Qa’ida’s critique of U.S. imperialism was dismissed as hating “freedom” (prompting Osama bin Laden to ask rhetorically why he didn’t attack Sweden). Other times, the terrorism label conceals what the state and those groups have in common. In that regard, demanding that a state regime founded in white supremacy deploy violence against parastatal white supremacist violence strikes me as asking an arsonist to be a firefighter.

KH: You are trained as both a lawyer and an anthropologist. In the book, you offer the reader insight into what occupying that double, hybrid orientation meant for you during your fieldwork. I was particularly struck by the way that friendship — construed legally and interpersonally — is at the core of this integrated research methodology. Can you tell us how and why friendship figured into your methodology of “ethnographic lawyering”?

DL: The research for this book was informed by my experiences working as part of a clinical legal team representing Ahmed Zuhair, a Saudi national held captive at Guantánamo Bay, Cuba, who was on a long-term hunger strike. Through visiting our client at the base, participating in federal court hearings, and many hours reviewing classified evidence in a government facility near the Pentagon, I developed some sense of how the kinds of transnational Muslim mobility that I research are understood by the national security bureaucracy. Mr. Zuhair was transferred to a rehabilitation facility in Saudi Arabia in 2009 and released several years later.

Ahmed Zuhair (Photo: Associated Press)

Working on the case also put me into a relationship of formally recognized (and elaborately structured) antagonism with the U.S. government as opposing counsel. In my anthropological research, this antagonism was important for signaling that I had different commitments from other researchers and journalists and could be trusted (which is not to say that they were always convinced!).

More broadly, I am invested in finding productive tensions between the distinct professional logics of anthropology and lawyering, recognizing that they can never fully align. I don’t think you can have an ethnographic relationship with someone you are representing as a lawyer that is both ethical and critical, or at least I don’t know how to reconcile this. Similarly, I can’t approach a private person as an ethnographic interlocutor if I’m going to be opposed to them in some kind of legal proceeding. But lawyering in relation to parties I wasn’t writing about could nevertheless ground the work — for me, ethnographic lawyering entails using everyday categories and artifacts of legal practice as conceptual and methodological scaffolding.

This gets to your question about friendship. Early in my research, one of the people who features prominently in the book, a Syrian mujahid called Abu Hamza, asked me for a “token of friendship” to assure him of my bona fides. After some time, I ended up participating in two amicus curiae (“friend of the court”) briefs on his behalf. In those situations, Abu Hamza was not my client; my clients, formally speaking, were NGOs that were intervening in his case to weigh in on the general legal framework under which his cases were being considered and did not seek to defend him on the facts. A friend of the court isn’t necessarily neutral, but is in theory trying to advise the court at some remove from the parties. In this instance, the professional ethical model of friendship with the court provided a capacious framing that allowed me to be useful to Abu Hamza — a concern in any ethnographic encounter — in a way that used law but did not entail us entering into an attorney-client relationship.

KH: So much of my thinking about the relationship between religion and political violence was shaped by reading scholars like Edward Said and Talal Asad, progenitors of scholarship that is critically attentive to the particularities and contingencies of discourse, culture, and history. So, I was really struck by your critique of their, well, critiques. You write that, “for all their merit”, their methods have left us “few tools to make sense of the acts of sacrifice that do occasionally take place in the name of Islam between people who lack any other tie of commonality”, and that we still need a way to “move beyond this problem of alterity — either Muslims are radically Other or Muslims are basically the same as Us — to instead treat the regulation of difference itself as the object of study.” Can you tell us more about what it would look like to shift our focus from making claims about alterity to thinking instead about the regulation of difference?

DL: My argument is directed at the milieu in which I was trained: “critical” strands of U.S. and U.K.-based Middle East studies that took certain tools for exposing logics of empire and secularism from people like Said and Asad, but did not know how to squarely address the one topic that basically everyone outside the field looked to us for insight on in the years after 9/11. There is a lacuna here when it comes to jihad practices, bounded on one side by Said’s difficulty in thinking with religion and, on the other, by the obliqueness of Asad’s engagement with the political. But the book is intended less as a critique of Said and Asad than of the rest of us for not expanding the horizon far enough beyond their pathbreaking contributions.

KH: Your book is deeply engaged with the work of Carl Schmitt, a fraught but canonical figure, known both for his membership in the Nazi party, and because his work has fundamentally shaped a century of (conservative and liberal) thinking about political theology. You focus on two tethered concepts from Schmitt: the enemy and sovereignty. About the enemy, you write, “If Carl Schmitt argued that politics was about the ability to distinguish between one’s friend and enemy, then speaking in the name of the universal is about making that decision on behalf of others.” You also write that, “the Jihad fighter — especially one who travels across national boundaries — is a universal enemy.” This really clarifies a way of seeing the world in terms of competing universalisms — jihad is both the subject and object of universalisms. That is, jihads make universalist claims and universalist claims are made about jihads. Is this — these competing universalisms — what you mean when you write that “jihads can help us see the broader world differently than we may have otherwise”?

DL: Yes! That’s a helpful reformulation of the book’s argument, and the choice of title as well. I would add a third concept of Schmitt’s that the book thinks with, namely that of the partisan. Unlike most other “canonical” (i.e. racist) thinkers, Schmitt at least took the antagonistic dimension of politics seriously and also theorized war knowing full well that nation-states were not the only parties to wage it. For Schmitt, the partisan was such a figure of fascination, of potential legitimacy and even nobility, but who ultimately sought to capture state power and was defending home and hearth. In contrast, in transnational jihads, the Arabic term “ansar” (often translated as “partisan”) is used for those who travel to other lands in order to fight for Islam. Schmitt — and on this point he largely agrees with his liberal counterparts — would dismiss these partisans as unmoored and unregulated bearers of violence. But The Universal Enemy sketches the transnational social and cultural worlds that would make the ansar legible and ground their activities as potentially legitimate in the eyes of at least some of the people they sought to help in places like Bosnia. The ansar teach us that not every outsider is a stranger. The concept gives some historical depth and conceptual suppleness to think through questions like: were these mujahids in Bosnia “fellow Muslims” or “foreign Arabs”? Were U.N. peacekeepers emissaries of the International Community or instruments of Western meddling? And, as Schmitt would remind us, who gets to make that choice is the crucial question.

KH: You also point out that, despite the abundance of re-engagement with Schmitt, we (being, I guess, Western political philosophy) lack a theory of political theology that crosses state borders, as you argue that jihad does. Our political theology, centered on the authority of sovereignty, can only ever see the world in terms of the state, while jihad is based on a conception of authority rooted in solidarity that can cross national borders. Can you explain this differentiation between sovereignty and solidarity in more depth? What kind of world order does each claim as its aspiration?

DL: In the scholarly literature that I’m familiar with, it’s not difficult to find people who are analytically or normatively dissatisfied with treating the nation-state as the primary site of politics. But the alternatives presented are nevertheless often wedded to the logic of sovereignty. Most “non-state actors” that engage in warfare are fighting to become states; many of the locally rooted and authentic forms of community posited as alternatives to sovereignty are often themselves just re-imagined as sovereignties on a smaller scale. Now there is one significant alternative model, which is that of transnational diasporas as sites of political work. But even here, diasporas are usually either unarmed and essentially at the mercy of states, or they are armed but use violence to achieve statehood. I am interested in how violence can be organized without accepting sovereignty as an ultimate goal.

This is why I see the jihad in Bosnia as an instance of armed solidarity involving travel to fight alongside fellow Muslims in the face of mass atrocities, even if they committed atrocities of their own in the process. Much of the literature on jihad focuses on goals like implementing Islamic law or creating an Islamic state; while many mujahids individually supported such ideas, it was not the official agenda of the jihad and indeed their leaders made public statements to that effect. Instead of having a narrow debate over the extent to which those positions were genuine or not, I want to draw attention to overlooked issues, like how the mujahids tried to balance respect for the authority of the Bosnian government while also asserting the right to act regardless of whether the government welcomed them or not, and how they coordinated with an army whose commanders were either secular Muslims or not Muslim at all.

KH: To close, I’d love to pick up your argument about practices of solidarity and ask something a bit broad. How have you been thinking about solidarity in this year which has, one could argue, been defined by the isolation of lockdown and the collectivity of uprising. What does — or can — solidarity look like right now?

DL: As you suggest, in this year we have seen two major challenges in thinking through solidarity: on the one hand, there is the glaring failure — indeed, refusal — of solidarity at the national level in terms of elite decisions to place capital over people, yet again. And, on the other hand, we have seen the flourishing forms of mutual aid and care that the insurrections against white supremacy have made more manifest. My worry, however, concerns the question of violence. When asked whether the antagonists in The Universal Enemy are engaged in regressive projects, my answer has been: sure, but if even a formation as problematic as this one has at least tried to organize violence transnationally in the face of American global hegemony, where does that leave the rest of us? To be honest, I don’t think the left — broadly construed — is talking enough about how violence can be organized and made accountable to our politics. There are recurring questions about building capacities for self-defense without devolving into vanguardism, masculinism, and performativity and about the relationship between self-defense and solidarity with others. And until this happens, I don’t see how we will be truly ready to confront what is to come.

Kali Handelman is an academic editor based in London. She is also the Manager of Program Development and London Regional Director at the Brooklyn Institute for Social Research and a Contributing Editor at the Revealer.

Darryl Li is an assistant professor of anthropology and an associate member of the law school at the University of Chicago. He is also an attorney licensed in New York and Illinois.