Representing Migration: Two photographers creating new ways to see history and sanctuary

Images that challenge us to see migration differently

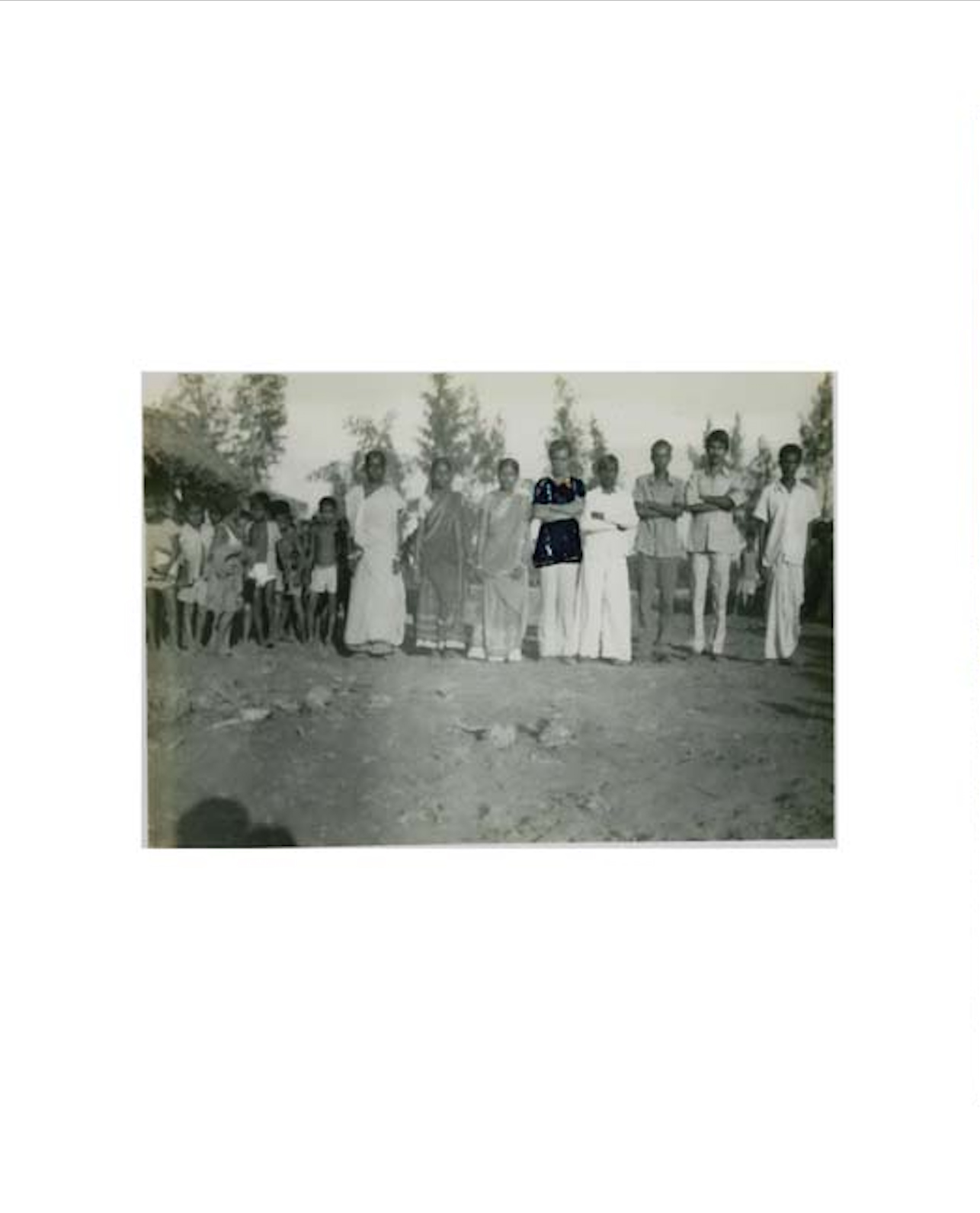

This photograph was taken in December, 1978 in front of Marichjhapi Primary School along with the teachers. In the middle Nirmal Dhali (Black shirt), head master of Marichjhapi School.

Upon gaining independence from British colonial rule in 1947, the Indian state of Bengal was partitioned, dividing East from West. The predominately Hindu West was made part of India and the Muslim-majority East was made a province of the newly created nation of Pakistan. West Bengal has remained part of India, while in 1971, East Bengal became the country of Bangladesh. Following the Partition, and the violence that ensued, thousands of displaced and poor Hindu refugees from East Bengal fled their homes and migrated to India. Eleven years later, in 1958, The Indian government implemented the Dandakaranya Project, intended to resettle the incoming East Bengali refugees by developing a home for them on tribal land in central-east India which has been described as “a vast area of primeval forests, uneven rainfall, and stony land.”

The project suffered many challenges. The land in Dandakaranya was considered unsuitable for farming, which was a blow to many of the refugees whose livelihoods had always come from agriculture. Instead of staying in Dandakaranya, many migrated to Marichjhapi, an uninhabited island in the mangrove forests on the southern tip of West Bengal, famous for its Bengal tigers and saltwater crocodiles. Their arrival was immediately met with hostility from the West Bengali leaders. Many were forced to return to Dandakaranya or were resettled in other parts of India. Between eight and ten thousand Bengali refugees, though, managed to remain in Marichjhapi, outlasting the initial removal orders.

Nishikanto fled to the opposite island during the evacuation but he has most vivid memories of their houses burning.

In an effort to force the remaining refugees out of Marichjhapi, the West Bengal government responded by stopping all movement in and out of Marichjhapi on January 27th, 1979. The government also withheld food and water from the refugees and sent thirty police officers to patrol the island. In May of that year, police officers surrounded the island, opened fire, and dumped the bodies of the people they shot into the river as others tried to flee. The media was barred from entering Marichjhapi during the assault, and while the government has said that fewer than five people died, some estimates have found that hundreds and maybe even thousands of Bengali refugees were killed in what came to be known as the Marichjhapi Massacre. There is still no official death toll.

Although the media attempted to cover what occurred at Marichjhapi closely at the time, the government’s revisionist history of the massacre dominated the public narrative since the massacre is not openly discussed. Thus, in her widely praised research on the displacement of Bengali refugees, Nilanjana Chatterjee, an anthropologist who wrote her dissertation on the massacre,[1] has called what happened in Marichjhapi an “event of interpretation.”

Now, Soumya Sankar Bose is attempting to shed light on this story, including new possibilities of what might have happened in Marichjhapi and pointing to the ongoing impact of this event. Bose is a photographer who was born in India a little over a decade after the massacre occurred, and his project about the massacre, Where The Birds Never Sing, is one of the 10 projects funded by the Magnum Foundation that explores both religion and immigration.

Nirmal Dhali(Head master) after 40 years at Dandokaronyo. during the evacuation he was arrested and was in Dumdum jail for eight years now living in a small village of Malkangiri, Orissa.

The multi-media project aims to weave together “several perspectives of the same narrative” with “the facts and fictions” of the Marichjhapi massacre to recreate a memory that Bose believes the government would prefer people forgot — like the actual number of people who died. For him, the ultimate success of the project is more than the digital mural where people can learn about the massacre and interact with what he will be creating and exhibiting in a contemporary gallery in Kolkota.

Success would be a tacit acknowledgment from the government that it even happened.

“The truth should be in front [of everyone]” said Bose.

For Bose, there is an urgency associated with this work. Although survivors have been vocal about what happened in Marichjhapi in 1979, many of the survivors are aging.

“If we don’t document it now, it will be lost forever,” says Bose.

Recreating a memory that many in power want to be erased is a herculean task, but Bose’s methods for achieving it are scrappy and ambitious. He is hoping to track and photograph survivors, as well as family members of those who were killed in the massacre. He will interview them and include their accounts in a growing archive of newspaper clippings, academic writing, and whatever else he can find about the massacre. In addition to the factual documents he and his partner, Barnali Ghosh, a videographer, will also employ actors to stage reenactments of the incident which they will photograph and film for documentation purposes.

During the evacuation in 1979, due to police firing all the refugee family got scattered here and there. Rabin Biswas’s family was among them. Later, after 30 years he reunited with them in a remote village of Orissa.

Bose’s work aims to recreate an event that happened forty years ago. But we can feel echoes of it in another migration crisis today. As migrants continue to flee Central America for the United States, and millions of asylum seekers arrive in Europe, immigration — and questions about how to represent immigration — is in the public spotlight. Most recently, the photo of Salvadoran migrant Oscar Alberto Martínez Ramírez and his nearly 2-year-old daughter Valeria face down on the bank of the Rio Grande in Matamoros, Mexico caused an uproar, with many wondering if a similarly graphic photo would have been published if the victims were white U.S. citizens.

Through her project, Living in Sanctuary, Cinthya Santos-Briones, another photographer who was awarded a grant from the Magnum Foundation for her project on religion and migration, is turning her lens on undocumented immigrants in the United States who have taken refuge in churches to avoid deportation. Santos-Briones hopes to provide a different lens through which we can look at immigrants.

Jorge Taborda, 65 years old, posed for the photograph taken at the Holy Cross Retreat Center in Las Cruces, New Mexico, where he took refuge to avoid being deported since May 2017. Jorge Taborda lives with his youngest son, Steve 15 years old, in a small bedroom at the Holy Cross Retreat Center in Las Cruces, New Mexico. There Jorge works as a volunteer helping in several tasks at the center.

Jorge Taborda, his wife Francia Benítez, and his eldest son, Jefferson, 23, arrived in the United States in 1998, fleeing the armed conflict and violence in Colombia, but their asylum request was denied in 2002. In 2017, Jorge Taborda received a call from his wife after ICE agents detained her at home. ICE also stopped his eldest son Jeff. Both His wife and his eldest son were deported to Colombia in June 2017. When Jorge Taborda was taking his youngest son to school, 14-year-old Steve and an American citizen, ICE agents were waiting for him outside the school to arrest him and take him to the Immigration Detention Center in El Paso, Texas, where his wife, France Benitez, and his eldest son, Jefferson, met. Immigration agents dressed as civilians told Taborda to follow them to the pass and they would hand him over to his wife and son. Initially Taborda had agreed to follow the ICE agents in his car, however, decided to seek refuge in the church of Our Lady of Health in Las Cruces. The ICE agents followed him to the church but did not enter and waited for hours for Taborda to leave. Then, with the help of the Communities of Faith and Action (CAFé), he was transferred to the Retreat Center of Santa Cruz in Mesilla Park, New Mexico, where the Franciscan priest, Thomas Smith, offered him indefinite Franciscan hospitality. December 3th 2018. Las Cruces, New Mexico, USA.

According to CBS News, there are more than 800 churches in the United States that shelter undocumented immigrants and families who are facing deportation; many immigrants have taken up the offer. A 2018 report by the group Sanctuary Not Deportation found that there are at least 36 people currently in churches around the country seeking refuge from deportation.

While the last two years have brought us some coverage of families seeking sanctuary in houses of worship, the intimate images featured in Santos-Briones’s body of work are different.

Santos-Briones husband is a Lutheran priest who works with the New Sanctuary Coalition, a volunteer-led organization based in New York that provides legal support and community services for immigrants and they once lived in a church where a majority of the church’s congregation were undocumented. According to Santos-Briones, there is no question of objectivity in her work. Many of the families she photographs are not only her subjects; they are an important part of her life.

“They are my friends, the parents of my godsons and goddaughters,” says Santos-Briones.

The project is personal for Santos-Briones and often, she goes beyond taking photographs.

“It’s the people that are so close to me that are facing deportation and at some point, I am not only documenting them, I’m also trying to support them.”

“Most of the time the media portrays them as vulnerable, and when I speak with them they say ‘I don’t want you to take a photo of me when I’m crying.’ So I am aware of these things,” she said.

After taking a shower, Daniela, the one on the left, and her sister Dulce, are sitting down in one of the church’s pews, waiting for their hair to dry. “We never thought of living in a church,” says Dulce. ¨I feel there are ghosts all around me and they see me. But I also like living here. It is a beautiful place¨. Since August 17, 2017, Dulce, Daniela and their brother, David, live, together with their mother, Amanda Morales, as refugees in the Episcopal Church of Holyrood, in Washington Heights, to avoid the deportation of their mother back to Guatemala.

For Dulce and Daniela, 10 and 9 years old respectively, to live in a church as refugees has not been easy, given that they had to leave behind their house, school and friends in Long Island. Their mother was the first undocumented migrant, in the last three decades, to take public sanctuary in the city of New York. After they moved to the church, Dulce and Daniela have suffered episodes of anxiety for fear that their mother will be deported and separated from them and her brother Daniel, 3 years old. October 20th, 2017. Manhattan New York,

Her images capture the mundane and ordinary moments of these families’ lives as they make peace with their new homes. There is also a sense of understanding in these photographs; seeking sanctuary is an intentional act, one of preservation rather than desperation. Rather than portraying her subjects as helpless, Santos-Briones is conscious about giving the families agency in her photographs.

Sijutno Sajuti and his wife, Dahlia, both 70 years old, reading the Koran in the room where they live since October 2017 at the Unitarian Universalist Church in Meriden, Connecticut. Sijutno Sajuti and his wife, Dahlia, are Muslims from Indonesia. In addition to praying every day five times a day, they also study the Koran. Although they live in a Unitarian Universalist church, they continue to practice their religion.

An office on the second floor of the church has been renovated as a dormitory for Sijutno Sajuti and his wife, Dahlia, while waiting for Sijutno’s deportation order to be stopped. The room is very small and only has a small window, a bed, a desk and a closet. Sijutno Sajuti and his wife, Dahlia, are known in the city of West Hartford, Connecticut for their focus on cultural education. He is an anthropologist and an educator and his wife teaches Indonesian cuisine and culture. In 2003, a federal judge ordered Sujitno Sajuti to leave the United States. In 2011, he was arrested by Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE), and detained for 67 days. Since then he had been living in Connecticut with temporary stay status until October of 2017 when he had to take sanctuary for fear of being deported. October 20th 2018. Connecticut, USA.

Despite the difference in their approach and subject matter, the overarching message Bose and Santos-Briones are trying to convey is essentially the same. Both are making work which directly responds to other, problematic, representations and misrepresentations of migration and the consequences of those portrayals. Bose’s project is in direct defiance of the attempted erasure of East Bengali refugees, and the state-sanctioned violence against them four decades ago that continues to reverberate today. In the United States, where the violence against immigrants coming from the Southern border is fast becoming normalized, Santos hopes to offer a different interpretation of what it means to be an immigrant living in the United States, fully human images that defy how too many people imagine (and fail to imagine) the people trying to make their homes here.

In the center, Amanda Morales, being blessed by the members of Holyrood church congregation, where since August 2017, Amanda and her family live in sanctuary. Every Sunday Amanda attends the Spanish Mass celebrated at 12 noon by Rev. Luis Barrios. “Amanda is the force of our community, the face of many mothers who are being deported and, separated from their children, we bless Amanda with our hands and souls” comments Rev. Luis Barrios while the members of the congregation bless her with their hands. In August 17, 2017 Amanda Morales an undocumented immigrant from Guatemala decided to take refuge in Holyrood Episcopal Church in Washington Heights, Manhattan with her three children, Dulce 10, Daniela 8 and David 3, for fear of she being deported. Amanda lives and works in New York since 2004. Since 2012, Amanda had been under supervision with immigration authorities and was complying with all that she was asked. In early May she was told to present herself with one-way ticket to Guatemala, on August 17, 2017 to be deported. September 26th 2017. Manhattan, New York

***

[1] Chatterjee, Nilanjana (1992). Midnight’s Unwanted Children: East Bengali Refugees and the Politics of Rehabilitation Unpublished doctorall dissertation). Brown University, Providence, RI.

***

Ashley Okwuosa is a Nigerian journalist currently based in New York. Her stories on immigration, education, and gender have been published on WNYC, Quartz Africa, OZY, Popula, and Latterly. She is a graduate of the Columbia Journalism School where she was a recipient of the African Pulitzer fellowship. She is currently working as a project lead for Maternal Figures, a maternal health research project that documents successful health interventions in Nigeria. The project is supported by a grant from The Brown Institute for Media Innovation

Cinthya Santos Briones’ interest in documentary photography emerged through the ethnographic work that she has done as an anthropologist in indigenous communities in Mexico, where she documented ceremonial and healing rituals, and processes of immigration to New York. Since then, her work has been influenced by the struggle for human rights, focusing on issues of migration, gender, and identity. Cinthya is a graduate of the Visual Journalism and Documentary Practice Program at the International Center of Photography. She received the Magnum Foundation Fellowship in 2016, the En Foco Fellowship in 2017, and was twice a fellow of the cultural arts fund in Mexico. Cinthya has published her work in New York Times, PDN, La Jornada, Vogue, Buzzfeed, The Nation Magazine, among others. Cinthya has worked in pro immigrant organizations in New York as a community organizer. Instagram: @cinthyasantosb

Soumya Sankar Bose completed a one-year diploma in Photography from Pathshala South Asian Media Institute, Dhaka. His project, “Full Moon on a Dark Night” was produced with Magnum Foundation’s Photography and Social Justice Fellowship in 2017. Soumya is also recipient of India Foundation for the Arts grant for the project, “Let’s Sing an Old Song” in 2015. His works have appeared in The New York Times, BBC Online, The Telegraph, The Indian Express, The Huffington Post, The Caravan and others. Soumya lives and works in Kolkata, India. Instagram: @soumyasankarbose

***

Published with support from the Henry R. Luce Initiative on Religion in International Affairs.