Religious Militancy Overseas and Its Messages at Home

A conversation with Suzanne Schneider about her new book, The Apocalypse and the End of History: Modern Jihad and the Crisis of Liberalism

I’ve been waiting for Suzanne Schneider’s book, The Apocalypse and the End of History: Modern Jihad and the Crisis of Liberalism, ever since I worked with Schneider on her first article for the Revealer back in 2015, “The Reformation Will Be Televised: On ISIS, Religious Authority and the Allure of Textual Simplicity.” Schneider is uniquely capable of combining the deepest expertise with incisive critique in writing that is not only accessible, but a pleasure to read — and her book fully delivers on that first article’s promise.

I’ve been waiting for Suzanne Schneider’s book, The Apocalypse and the End of History: Modern Jihad and the Crisis of Liberalism, ever since I worked with Schneider on her first article for the Revealer back in 2015, “The Reformation Will Be Televised: On ISIS, Religious Authority and the Allure of Textual Simplicity.” Schneider is uniquely capable of combining the deepest expertise with incisive critique in writing that is not only accessible, but a pleasure to read — and her book fully delivers on that first article’s promise.

The Apocalypse and the End of History is a rich inquiry into the history and current nature of political violence. Taking as its premise that to understand violence abroad, we have to take a much closer look at home, the book methodically explains the interwoven roles of religion, neoliberalism, democracy, economics, colonialism and media in producing not only “jihadi” violence, but drone strikes and mass shootings. The book is not about flat equivalences, but about asking challenging questions about how we got here and where we’re going. I always learn from my conversations with Schneider and am very glad that we had a chance to talk about her book on the occasion of its publication.

Kali Handelman: This might be a wildly unfair question, especially right out of the gate, but… If there were one thing you could change about the way we talk about jihad, what would it be?

Suzanne Schneider: I know you said one thing, but I’m going to respond with two that are intimately linked (so it’s not quite cheating): first, jihad is not a singular phenomenon that assumes the same form over time, such that the ISIS jihad is not functionally the same thing as the Bosnian jihad in the early 1990s, which is itself very different than the one declared by the Ottoman Empire in 1914, which likewise differed from medieval declarations of jihad during the Crusades. Recognizing jihad as a diverse and historically evolving practice makes it possible to cast aside the biggest misconception in the West, namely that it is an instantiation of medieval barbarism left over from less enlightened times. On the contrary, and this is the second thing, I’ve come to the conclusion that should be far more unsettling, namely that today’s jihad–at least in its Islamic State guise (and I really want to underscore here that I am specifically talking about ISIS)–is a hypermodern phenomenon that has a great deal to teach us not about the past, but about a possible future.

Suzanne Schneider: I know you said one thing, but I’m going to respond with two that are intimately linked (so it’s not quite cheating): first, jihad is not a singular phenomenon that assumes the same form over time, such that the ISIS jihad is not functionally the same thing as the Bosnian jihad in the early 1990s, which is itself very different than the one declared by the Ottoman Empire in 1914, which likewise differed from medieval declarations of jihad during the Crusades. Recognizing jihad as a diverse and historically evolving practice makes it possible to cast aside the biggest misconception in the West, namely that it is an instantiation of medieval barbarism left over from less enlightened times. On the contrary, and this is the second thing, I’ve come to the conclusion that should be far more unsettling, namely that today’s jihad–at least in its Islamic State guise (and I really want to underscore here that I am specifically talking about ISIS)–is a hypermodern phenomenon that has a great deal to teach us not about the past, but about a possible future.

KH: This book is, in a sense, a response to the question you pose in the introduction: “Why have the last several decades proven so generative for a particular type of religious militancy, and what does this fact indicate not merely about conditions ‘over there” but about those far closer to home?’ In responding, you argue convincingly that we are in the midst of a global change in our relationships to violence and thus, we need to consider much more deeply what you call an “uncomfortable proximity” between “home” and “over there” — that is, to put it bluntly, between mujahideen and mass shooters. There are a number of references to media, again, “ours” and “theirs,” in the book. Through these references, you put “our” Glenn Beck, Bill Maher, Braveheart, and Aladdin and “their” Dabiq and al-Naba in close proximity to one another. I wonder if you could put a finer point on the role of media — film, TV, news, marketing newsletters, etc. — as it impacts our changing relationship to violence? What does this media do? And what does it tell us about our “uncomfortable proximity”?

SS: I think readers of the Revealer probably already know this, but it is worth underscoring the extent to which new forms of spectacular violence exist in a relationship of codependence with the media channels that cover them. There are a number of facets to this relationship but we should note that it is bi-directional: Suicide attacks and on-screen excecutions are tailor-made for a world with instantaneous communication networks, a 24/7 news cycle, and globalized social media — but so too the profit model of capitalist journalism incentivizes sensational coverage. So there is something mutually constitutive in nature about contemporary terrorism, media, and spectacle — that is the first thing to note.

Looking at Islamic State media offers another point where we can and should push back against the idea that the group is “barbaric” or “medieval,” because the style of spectacular violence they embrace is in part determined by this media ecosystem. Moreover, a more nuanced reading of this violence reveals that far from being the polar opposite of “our” enlightened values, it is a dark mirror of capitalism’s inner logic. After all, as tragic as it may be in ethical terms, executing a hostage in the Syrian desert accomplishes very little if that video cannot be shared and watched the world over. It is certainly true that such executions offered the Islamic State unique opportunities to humiliate the world’s greatest superpower, inflicting a psychological blow that far exceeded the group’s material capacities.

(ISIS Fighters at the Syrian Border. Photo by Medyan Dairieh for ZUMA Press.)

Given the real asymmetries of power involved, politics here is largely reduced to spectacle and–perhaps most distressing from an ethical perspective–victims are regarded as props in the production of such spectacle. Nor is this merely a continuation of the forms of violence practiced by earlier generations of revolutionaries, who Brian Michael Jenkis aptly described in 1975 when he said “terrorists want a lot of people watching, not a lot of people dead.” Contrast this with a more recent Islamic State directive: “The objective of hostage-taking in the lands of disbelief—and specifically in relation to just terror operations—is not to hold large numbers of the kuffar (disbelievers) hostage in order to negotiate one’s demands. Rather, the objective is to create as much carnage and terror as one possibly can until Allah decrees his appointed time and the enemies of Allah storm his location or succeed in killing him.”

I find it noteworthy that the victims here are regarded as utterly disposable, which is part of why I think there is something nihilist about the Islamic State’s deployment of spectacular violence. However attention grabbing, such attacks are unable to replace secular modes of governance with the Caliphate; they will not conquer Rome (meaning the West more generally) or impose shari‘a globally. They are a means to an “end.” But that end is a tragic farce that bears no chance of realization.

Of course, it is not shari‘a that has bequeathed us with the idea of the disposable human body, but modern capitalism — a fact the COVID-19 pandemic has exposed in all its brutal force. That is to say, if there is something “barbaric” about the Islamic State, it is a barbarism that is also present in the broader world. I think many people in the West remain very uncomfortable with the idea that a group like the Islamic State might actually be a dark reflection of liberalism’s inner logic rather than its pure negation — a phenomenon that reveals what is latent in the present political, economic, and social order. In fact, not unlike other reactionary movements, there is a dual motion of mimicry and negation involved here whereby ISIS ostensibly rejects the principles of the prevailing (neo)liberal order all while it is unable to shake many of that system’s foundational assumptions and modes of mobilization.

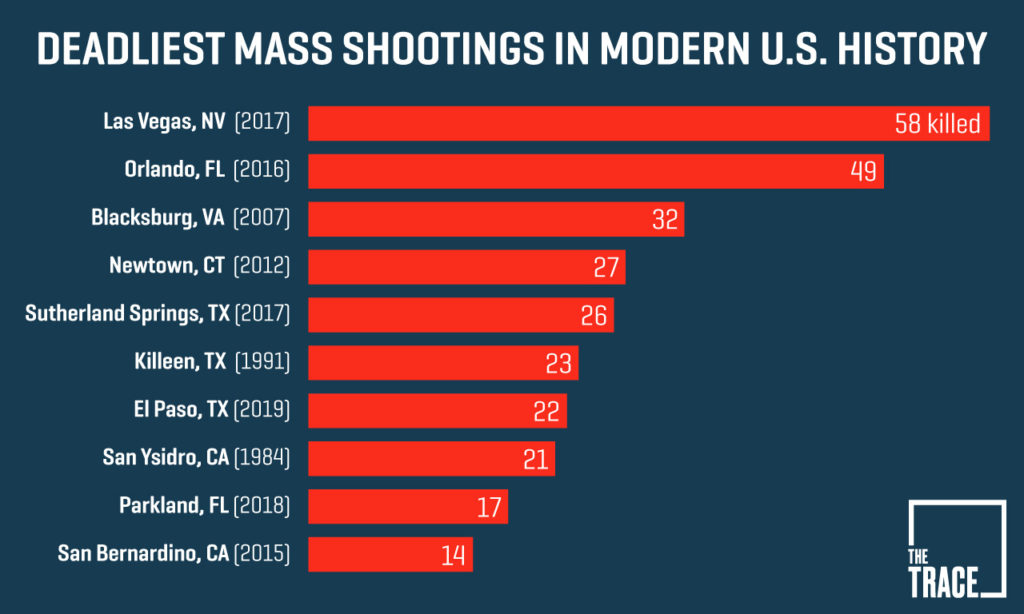

Within this context, the idea of an absolute difference between “us” and “them,” or “our” violence and “theirs,” no doubt does some important psychological work, but it also is a crucial part of system preservation — of reassuring people that the Caliphate’s violence comes from somewhere foreign or exotic, the medieval world or the Islamic one — elsewhere in short. That is why cases involving mass shooters who have sworn allegiance to the Caliphate, such as the Pulse nightclub shooting in Orlando, or the attack at a San Bernardino office building, are so challenging to process. The American public desperately wants some differentiation between such attacks and the rather frequent mass shootings by white, disaffected Christian men. And it is noteworthy that ISIS too wants differentiation, going so far as to instruct would-be assailants in Western countries to “leave some kind of evidence or insignia identifying the motive and allegiance to the Khalifah [Caliph]” lest “the operation be mistaken for one of the many random acts of violence that plague the West.”

KH: To come back more directly to religion, you write in the book about how “we might wonder how militants’ rather dim view of democracy intersects with the waning faith in that system in the west” and ask “what might the Islamic State’s approach to governance have to teach us about the changing nature of political life more broadly?” I wondered if we might think a bit more about what work the term “faith” is doing here. What does it mean, from a religious studies perspective, to have “faith” in a political system and how might that, too, be a discursive symptom of particular Protestant experience? What work does the word “faith” do in revealing or obscuring the role of religion and/or religious discourse in how we think about politics? And how might it help us better understand losses of faith, like, say, the January 6 Trumpist attack on the Capital?

KH: To come back more directly to religion, you write in the book about how “we might wonder how militants’ rather dim view of democracy intersects with the waning faith in that system in the west” and ask “what might the Islamic State’s approach to governance have to teach us about the changing nature of political life more broadly?” I wondered if we might think a bit more about what work the term “faith” is doing here. What does it mean, from a religious studies perspective, to have “faith” in a political system and how might that, too, be a discursive symptom of particular Protestant experience? What work does the word “faith” do in revealing or obscuring the role of religion and/or religious discourse in how we think about politics? And how might it help us better understand losses of faith, like, say, the January 6 Trumpist attack on the Capital?

SS: It’s an excellent and interesting question. I think the idioms of faith suggest themselves when talking about democracy because there are two primary ways of maintaining a state: legitimacy and coercion. There is a tendency to regard the former as having something to do with faith – i.e. for democracy to work, the people have to believe in it. We still have not exited the land of idealism here, which imagines that states and societies can be remade by altering the way people think about them. I’m being a little cheeky, of course, but only a little: this was the basic assumption that has undergirded countless democracy promotion programs in the Middle East and North Africa, and that was also central to imperial exploits like the Iraq war. It is an incredibly shallow view of democracy.

All that said, I don’t dismiss the idiom of faith entirely. Maintaining stable governments over time does require some sort of popular buy-in, belief even, in the legitimacy of the system in question. But people do not believe in democracy in an abstract ideological fashion as being “the best” style of government just because it is repeated ad nauseum, but because it delivers certain material benefits that are apparent in their everyday lives. Without such benefits, you are left with the hollowed-out shell of ideology, one that is increasingly contradicted by daily experience.

What does this look like in practice? Anecdotes are limited as analytic tools, but I’m going to offer one anyway because I think it does speak to something broader and more elemental. My mom is engaged in a dispute with Medicaid over receiving certain services for her sister, who is an 85-year old with severe cerebral palsy and who has few personal assets and lives in a nursing home. But the process of taking up a complaint with a government agency has all the joys of calling Verizon to haggle about your bill: the endless phone tree and web of people who lack the authority to actually help you. So she has taken to contacting her representative in Congress as well as the representative in my aunt’s district, writing and calling in almost weekly for well over a year to see if they can help with her dispute. She got a response from a staffer once, I believe, just to request more information, but it has otherwise been radio silence. Now, this is just a personal story, but it points to a substantive lack of democratic responsiveness when the mechanisms of government are just as opaque and unaccountable as a sprawling multinational corporation. Democracy is reduced to the ability to vote every two or four years for the person who will not respond to, to say nothing of address, your real needs.

This type of experience is corrosive to people’s “faith” in democracy because it reflects a material failure of democratic governance. This leaves the door open to entertaining various authoritarian alternatives: maybe the military would run the show with greater efficiency, or a swamp-drainer could Make Bureaucracy Great Again. It isn’t that ideology is unimportant, but it cannot be maintained without some degree of correspondence to people’s actual experiences. What’s happening in this case is a legitimation crisis, where belief in the capacity of the existing order to deliver anything of substance is wavering. And back to the original point, if this experience–it is really a loss of faith in some sense–becomes widely shared, it is detrimental to maintaining the present order other than through increased reliance on coercion.

KH: You make a really compelling argument in the book about neoliberalism as a “colonial blowback,” that is, something “prefigured — if not actively constructed — in the colonial world.” Which led me to want to ask you about decolonization. The attention you pay to clearly defining neoliberalism is so valuable — unpicking the elements of privatization, management, and individualism — in all its forms and impacts. If the goal is to build “a world safe from authoritarian politics and nihilist violence in all its guises” what role does decolonization play?

SS: Yes, it has been noteworthy to see how certain features of colonial life have become evident in advanced industrialized countries like the U.S. and U.K., whether it’s race-to-the-bottom tax avoidance schemes designed to lure major corporations or the increased presence of private security personnel guarding the estates of the very wealthy. The bigger picture here, and the reason that thinking in terms of colonial predecessors is useful, is one of state capture and redeployment as a tool for advancing capital. Perhaps the key function of the colonial state in a place like Nigeria or India was to undermine and/or punish any sort of democratic resistance to the violence–material, environmental, social–inherent in this order.

It might be tempting to contrast the present with the so-called “good old days” of earlier decades, when labor was strong and inequality was far less severe in Western Europe or the U.S. It is certainly the case that those years represented an instance of increased democratization of the state structure, which yielded expanded franchise, progressive taxation, and curtailed corporate power, and did enable certain gains for the white middle classes. Yet this accord still rested on a great deal of imperial violence abroad: witness the post-war oil politics in Nigeria, Iran, and Saudi Arabia. This dynamic literally built the modern state of Saudi Arabia (as Robert Vitalis has vividly demonstrated in America’s Kingdom), deposed Prime Minister Mossadegh in Iran, and propelled Nigeria into a non-sovereign state status, where the government largely acted to advance the interest Royal Dutch Shell regardless of the incredible environmental damage caused by oil production — from which until very recently, people have been blocked from seeking any redress. What we see in these latter instances, and I think have begun to see in the Global North as well, is the inability or unwillingness of the state to intervene on behalf of the public good. It is rather a mechanism for advancing private power and undermining any popular resistance to the vast inequities involved through violence.

Given this context, the idea and practice of decolonization can be helpful for a few reasons. First it demonstrates that the post-WWII period was not a Golden Age for all involved. Democratic gains and better material conditions in the Global North cannot be built upon the continued degradation of those in the Global South — and indeed, part of the conceptual task that decolonization can assist with is breaking away from the idea that human flourishing is a zero sum game with winners and losers. Certainly those of us in the West can learn from anti-colonial revolutions in Asia and Africa, where people expressed a clear desire to attain a state that could work to advance the public good by taming the rapacious power of capital. But we might also learn something about why some of these revolutionary projects faltered: how appeals to national unity can defer dealing with underlying structural inequalities or breed a new crop of authoritarian rulers.

Finally, and this brings us back to the question of state capacity, decolonization does not entail the abandonment of the state, but rather its subjection to democratic control. This would entail not only genuine public oversight over the use of violence, but the evolution of the state structure into a vehicle that could actively intervene on behalf of the public good. Decolonizing education, for instance, is not merely about diversifying syllabi or ensuring teachers take part in anti-bias training. These things can be good – but they can also be co-opted to forestall needed structural changes related to access, funding, facilities, staffing, and support services — not to mention how we envision the purpose of schooling, which has narrowed under neoliberalism so as to be basically market competitiveness and economic success.

To keep with this example, decolonizing education thus demands a few interlocking things: to articulate a far more capacious view of education and learning that currently in circulation, one that regards children as human beings rather than mere units of economic productivity; to redress the historic damage wrought by education–both the lack of it, and its provision (thinking of Lakota boarding schools in my home state of South Dakota)–within BIPOC communities; to wrestle with the legacies of white supremacy on both an epistemological and structural level; and to use the state as a vehicle for advancing democratic alternatives. Decolonization means living in a society where these aspirations are achievable — or at least deemed less utopian than establishing a Silicon Valley outpost on Mars.

Kali Handelman is an academic editor based in London. She is also the Manager of Program Development and London Regional Director at the Brooklyn Institute for Social Research and a Contributing Editor at the Revealer.

Suzanne Schneider is Deputy Director and Core Faculty at the Brooklyn Institute for Social Research, specializing in the political and social history of the modern Middle East. She is the author of Mandatory Separation: Religion, Education, and Mass Politics in Palestine and writes broadly about political violence, militancy, and American foreign policy.