Religion in Lovecraft Country

A review of the racial and religious messages in the HBO horror series

Horror fans rejoice. We are, apparently, living in a golden age. Sure, this may be because we’re living in horrific times, with pandemics, authoritarians, and impending apocalypse peering over our windowsills. But why worry? Snuggle up to your screen instead.

Horror fans rejoice. We are, apparently, living in a golden age. Sure, this may be because we’re living in horrific times, with pandemics, authoritarians, and impending apocalypse peering over our windowsills. But why worry? Snuggle up to your screen instead.

Lately, my screen has been filled with Lovecraft Country, the 2020 HBO series by showrunner Misha Green, based on Matt Ruff’s novel of the same name. Part of the Black horror renaissance launched by the 2017 film Get Out (director Jordan Peele gets an executive producer credit here), the show narrates the pulp-fiction adventures of hero Atticus Freeman (Jonathan Majors) and an amiable cast of supporting characters, each of whom gets a star turn in one of its ten hour-long episodes. Plot twists abound. The story begins with Atticus returning home from the Korean War to 1950s Chicago. It then proceeds to slowly pull back the onion-skin secrets of a multilayered mythology.

The title offers the first clue to cracking these coded mysteries, with its reference to the notoriously racist progenitor of modern horror fiction, H.P. Lovecraft. What and where is “Lovecraft Country”? Green’s show, I think, implies two answers to this question — one pertaining to its political mission, the other to its sly take on modern religion.

First, and most scathingly, “Lovecraft Country” is America, the white-dominated United States. It’s a place where hidden monsters lurk on every corner and even polite faces can turn deadly in an instant. As in the acclaimed Get Out, the horror genre becomes a means of expressing a very real sense of dread. Supernaturalisms are literalized metaphors. In whites-only “sundown towns,” night really does bring monsters. In redlined neighborhoods, houses really are haunted. Keenly interested in how Black bodies can safely navigate such spaces, Lovecraft Country spends much of its time on the road with Atticus’ uncle George (Courtney B. Vance) and aunt Hippolyta (Aunjanue Ellis), who publish a Safe Negro Travel Guide that alerts middle-class Black motorists to lurking dangers. This is a historically accurate detail, recalling the Negro Motorist Green Book. The show’s signature move is to overlay this history with supernatural horror, much as the Freemans’ daughter Dee (Jada Harris) draws literal monsters on her parents’ road map. She knows that supernaturalisms reveal reality like little else can.

Second, and just as centrally, “Lovecraft Country” names the world of speculative fiction, the cosmos conjured by Lovecraft and other genre writers. This territory, I would argue, strongly overlaps with the cosmos of comparative religion, the academic discipline. For the past century, pulp fiction has been a sponge for witches, sorcerers, gods, and other supernatural beings labeled as “magic,” “superstition,” or “folklore” and thus relegated to the sidelines of “religion” proper. It has also, if less frequently, creatively poached symbols and stories from canonical religious scriptures. Fiction writers even poach from scholarly tomes to construct their mysteriously mythographic worlds.

Writing in a moment when a man known as the “Q shaman” has just stormed the U.S. Capitol, it seems safe to say that “Lovecraft Country” and its conspiratorial religiosity are still with us. Who better than Lovecraft to decipher the arcane symbolic banners carried by the white-nationalist mob of January 6 — including, but not limited to, the banners dedicated to the semi-satirical alt-right deity Kek, a frog-headed “god of chaos and darkness.”

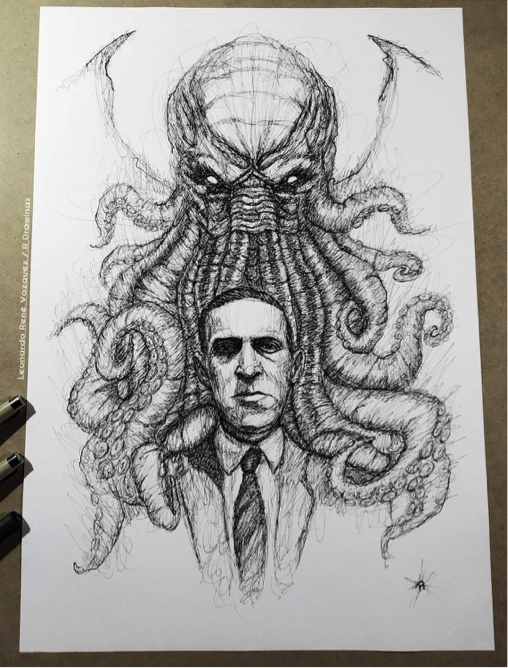

Racism was, after all, central to how Lovecraft wrote horror. His stories overflow with dusky-hued monsters, Black bodies subjected to Frankenstein experiments, and white men killing themselves at the faintest hint of a non-white ancestor. Even Cthulhu — a tentacled oceanic eruption now hailed by some as a restorative myth for the Anthropocene—first appears as a “fetish” object in a wild “Voodoo” ritual in Louisiana.

We should all cheer the World Fantasy Awards for, in 2015, getting Lovecraft’s racist head off the statuettes handed to acclaimed writers of speculative fiction.

We should all cheer the World Fantasy Awards for, in 2015, getting Lovecraft’s racist head off the statuettes handed to acclaimed writers of speculative fiction.

Still, lopping off the head does not kill the hydra. Lovecraft’s stickily tentacular mind is so deeply entangled in contemporary horror that it may be impossible to extract. Recent writers have been opting instead to reshape it from within. Multi-award-winning sci-fi novelist N.K. Jemisin, for instance, intentionally centered her latest book, The City We Became (2020), on Lovecraftian themes, seeing it as a “kind of a deep dive into how pathological racists think” that could allow her, as a Black woman, to reinvent the genre from the ground up.

Still, lopping off the head does not kill the hydra. Lovecraft’s stickily tentacular mind is so deeply entangled in contemporary horror that it may be impossible to extract. Recent writers have been opting instead to reshape it from within. Multi-award-winning sci-fi novelist N.K. Jemisin, for instance, intentionally centered her latest book, The City We Became (2020), on Lovecraftian themes, seeing it as a “kind of a deep dive into how pathological racists think” that could allow her, as a Black woman, to reinvent the genre from the ground up.

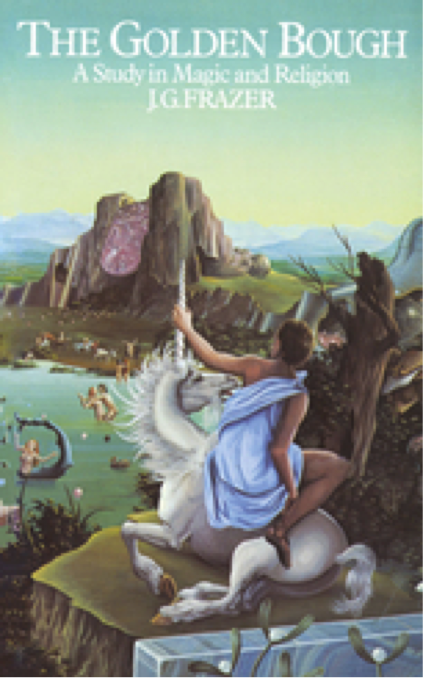

Does the academic discipline of comparative religion require similar treatment? Lovecraft’s borrowings from comparative religion are quite overt. Not only do his “weird tales” of the 1920s and 30s develop a pantheon of ancient gods or “Great Old Ones,” out of Egyptian, Druidic, and other mythologies. His most famous story, “The Call of Cthulhu,” even features a professor of Semitic languages obsessed with James Frazer’s Golden Bough, that classic tome.

Frazer and Lovecraft. They’re a perverse pair, but a telling one. Frazer — the armchair anthropologist whose grand narrative about human civilization progressing from “magic” to “religion” to “science” relied on imperial, racialized ideas about social evolution. Frazer — who, like Lovecraft, thought that even the most modern of men were haunted by the mad ghosts of ancient human sacrifice. Frazer — who twenty-first century scholars of religion have tried so hard to forget. Forgetting, alas, is not so easy. Tentacled minds live on. By the 1920s, The Golden Bough was a global literary sensation, so it is not particularly surprising that it makes a cameo appearance in “Cthulhu.” It is perhaps more surprising that the study of religion has, until recently, done so little to explore how Victorian comparative religion lived on in the world of imaginative literature even as it died out in academe. Standard histories of the discipline recount the rise and fall of university departments, where Frazer had mostly hit the dustbin by 1950, if not earlier. A whole counter-history of religious studies is suggested by the psychedelic 1971 Macmillan paperback edition[1] of The Golden Bough:

After watching Misha Green’s show, these peacenik pastels appear in a darker light. That unicorn looks out onto Lovecraft Country — a country unable to see, much less map, its own whiteness, which is what makes that whiteness so dangerous.

After watching Misha Green’s show, these peacenik pastels appear in a darker light. That unicorn looks out onto Lovecraft Country — a country unable to see, much less map, its own whiteness, which is what makes that whiteness so dangerous.

“Magic,” Frazer’s grand theme, looms large in Lovecraft Country. What is it? Who controls it? The show’s second episode culminates in a rite conducted by members of a secret society called the Order of the Ancient Dawn, who wear robes that are explicitly compared to those of the Ku Klux Klan. In an inversion of Lovecraftian miscegenation, the horror here is that Atticus is the lone surviving descendent of some kind of white supremacist mage, and that mage’s followers now need his blood for their dark ritual.

As we learn, the ritual is meant to restore the racial and gendered hierarchies that were disrupted when “that bitch Eve” ate the apple, reestablishing a white-supremacist, patriarchal Eden wherein Samuel Braithwhite, a leader of the Ancient Dawn, will be immortal, a new Adam. (Scandal fans will recognize Braithwhite as Tony Goldwyn, who played the star-crossed love to Kerry Washington’s Olivia Pope, on the Shonda Rhimes series. Seeing him in those grand master robes feels like an intertextual gut punch).

As we learn, the ritual is meant to restore the racial and gendered hierarchies that were disrupted when “that bitch Eve” ate the apple, reestablishing a white-supremacist, patriarchal Eden wherein Samuel Braithwhite, a leader of the Ancient Dawn, will be immortal, a new Adam. (Scandal fans will recognize Braithwhite as Tony Goldwyn, who played the star-crossed love to Kerry Washington’s Olivia Pope, on the Shonda Rhimes series. Seeing him in those grand master robes feels like an intertextual gut punch).

The Order of the Ancient Dawn is a quintessentially Lovecraftian religion. Its name an apparent riff on the Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn — the Victorian occult society that eventually counted among its members (actual or alleged) W.B. Yeats, Bram Stoker, and Lovecraft himself — the group gestures to a whole universe of fin-de-siècle religious organizations like Madame Blavatsky’s Theosophical Society. Lovecraft Country nails the aesthetic of this universe — equal parts occult mystery, weird science, and mundane bureaucracy. It also carefully flags occultism’s racial exclusions, as with the Prince Hall Freemasons. Were these what historian Judith Weisenfeld would call “religio-racial movements”? Perhaps. They certainly thought about religion in racialized terms, as with Blavatsky’s “root races” and “Great White Lodge.” So did the eclectic array of parallel movements in their general orbit, from Chicago’s Moorish Science Temple to, farther afield in British India, the anticolonial Arya Samaj.

Braithwhite’s daughter Christina (Abbey Lee Kershaw) describes the Order of the Ancient Dawn at one point as “a group of powerful men who wield magic. They don’t allow women to join.” Tellingly, she omits the word “white” — a slip not lost on her listener, Ruby Baptiste (Wunme Mosaku). Although outraged by the Order’s sexism, Christina wants nothing more than to join its whites-only club.

Green’s show thinks intersectionally, seeing race and gender oppressions as structurally intertwined, even as Christina refuses to. Throughout, it’s attuned to how race, gender, and sexuality overlap, and it allows its characters to slough identities in suggestive and sometimes grotesque ways. It even asks how U.S. racism has intersected with U.S. empire; there’s an entire episode set in U.S.-occupied Korea, scripted mostly in Korean and centering on a kumiho, a sort of fox-tailed incubus from Korean folklore.

Green’s show thinks intersectionally, seeing race and gender oppressions as structurally intertwined, even as Christina refuses to. Throughout, it’s attuned to how race, gender, and sexuality overlap, and it allows its characters to slough identities in suggestive and sometimes grotesque ways. It even asks how U.S. racism has intersected with U.S. empire; there’s an entire episode set in U.S.-occupied Korea, scripted mostly in Korean and centering on a kumiho, a sort of fox-tailed incubus from Korean folklore.

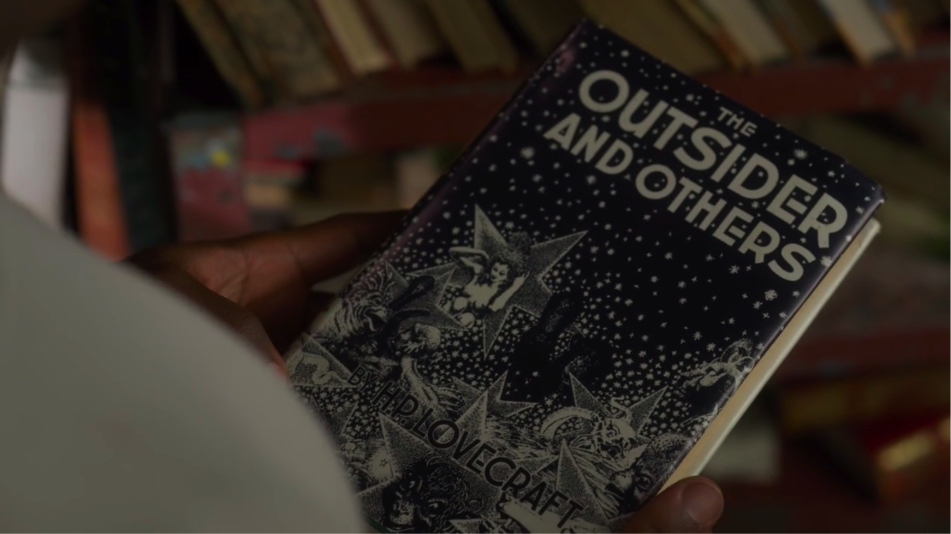

Clearly, the show’s mythologies go way beyond the Garden of Eden. Although our characters occasionally attend church to affirm their faith in God, their affirmations feel sort of like the heteronormative marriages tacked on at the end of Shakespeare’s gender-bender plays. By paying lip service to orthodoxy, the show is giving us permission to delight in the transgressively heterodox supernaturalisms that it so clearly adores. Atticus may be hunting for the original Adam’s magical Book of Names, with its antique leather binding, but his real bibles are postwar paperbacks of Bram Stoker, Alexandre Dumas, and, yes, Lovecraft.

This is a love-hate relationship. Green and her team want to critique pulp fiction’s racist past while also delivering pulp’s trademark pleasures. That’s a hard tonal feat to pull off — and, I would add, to write about. Any show that veers from serious, almost-sacramental meditations on the 1921 Tulsa massacre and the 1955 murder of Emmett Till to playfully precise visual quotations from films like Indiana Jones and The Goonies is bound to be a bumpy ride.

This is a love-hate relationship. Green and her team want to critique pulp fiction’s racist past while also delivering pulp’s trademark pleasures. That’s a hard tonal feat to pull off — and, I would add, to write about. Any show that veers from serious, almost-sacramental meditations on the 1921 Tulsa massacre and the 1955 murder of Emmett Till to playfully precise visual quotations from films like Indiana Jones and The Goonies is bound to be a bumpy ride.

Take, for example, the disorienting opening sequence, which begins with black-and-white footage of a soldier fighting his way through a World War I trench. He looks up to see a bomb exploding into bright orange and suddenly realizes that the sky above is pulsing not just with airplanes but also with UFOs and winged monsters, who belch technicolor flame onto a vast hellscape. Clambering out of the trench, he’s like Dorothy emerging into an unholy full-color Oz. There are no witches, but there is a fuchsia-skinned alien beamed down from a UFO in her green bikini and approaching him with an air of coy menace:

They briefly embrace before being interrupted by a giant tentacled creature.

They briefly embrace before being interrupted by a giant tentacled creature.

A baseball player suddenly appears, rescuing the duo by smashing the monster into a puddle of green slime with his bat. “I gotcha, kid,” he says. He doesn’t. The green slime slurps itself back together, with the monster about to devour all three of them . . . when our dreamer awakens. Atticus is in the back seat of a segregated bus, crossing over the Kentucky border into the wheat fields of the nominally unsegregated Midwest. The soundtrack cuts to a 1950s classic: Sh-boom, sh-boom. Life could be a dream, sweetheart. It, most obviously, is not.

A baseball player suddenly appears, rescuing the duo by smashing the monster into a puddle of green slime with his bat. “I gotcha, kid,” he says. He doesn’t. The green slime slurps itself back together, with the monster about to devour all three of them . . . when our dreamer awakens. Atticus is in the back seat of a segregated bus, crossing over the Kentucky border into the wheat fields of the nominally unsegregated Midwest. The soundtrack cuts to a 1950s classic: Sh-boom, sh-boom. Life could be a dream, sweetheart. It, most obviously, is not.

Three minutes into Lovecraft Country and its aesthetic pieces are in place. Wildly pulpy pastiche. Crazed anachronism. Symbols dense enough to need a decoder ring — or the internet. The baseball player, Dodgers jersey #42, is Jackie Robinson, the first Black American to play in the major league. The tentacled monster is clearly Cthulhu, who also slurpily reconstitutes himself when smashed. If the dream is allegory, the unkillable creature is white supremacism. Just when Robinson thinks he’s vanquished it, it returns. This is a calling card of sorts for Green’s show. It too is trying to slay Lovecraftian monsters. At the same time — and this gets at what’s jaggedly interesting here — it wants to keep them alive so they can continue to ooze narrative pleasures.

When Atticus wakes up, he has a copy of Edgar Rice Burrough’s A Princess of Mars on his lap. A lady seated near him asks (eyebrow raised) why he is reading a book about a Confederate officer who is magically transported to Mars by a sacred Apache cave. “Stories are like people,” Atticus replies. “Loving them doesn’t make them perfect. You just try and cherish them, overlook their flaws.” “But the flaws are still there,” the lady counters. “Yeah they are, but I love pulp stories.” Lovecraft Country loves them too. It even loves Lovecraft (despite Green herself not being a “huge fan”).

“The past is a living thing,” remarks a character in Lovecraft Country. It is not, one might add, even past. In keeping with this claim, the show toggles not just between dreams and reality, but between historical periods. It is a televisual time machine, with a retro-futuristic steampunk aesthetic.

It is, in the first instance, a period piece set in 1950s Chicago, and it delights in the clothes, cars, and muted monochromes of that era. Its nerd-chic is perhaps best exemplified by Letitia Lewis (Jurnee Smollett), once “the only female member of the South Side Science Fiction Club” and now a glamorous romantic lead.

It is, in the first instance, a period piece set in 1950s Chicago, and it delights in the clothes, cars, and muted monochromes of that era. Its nerd-chic is perhaps best exemplified by Letitia Lewis (Jurnee Smollett), once “the only female member of the South Side Science Fiction Club” and now a glamorous romantic lead.

The Jim-Crow 1950s are just home base, however. Our postwar-chic gang of heroes stumbles into creepy Victorian mansions.

The Jim-Crow 1950s are just home base, however. Our postwar-chic gang of heroes stumbles into creepy Victorian mansions.

They also stumble forward in time— encountering, say, a seven-foot tall Afrofuturist robot uttering the God-like words “I am”:

They also stumble forward in time— encountering, say, a seven-foot tall Afrofuturist robot uttering the God-like words “I am”:

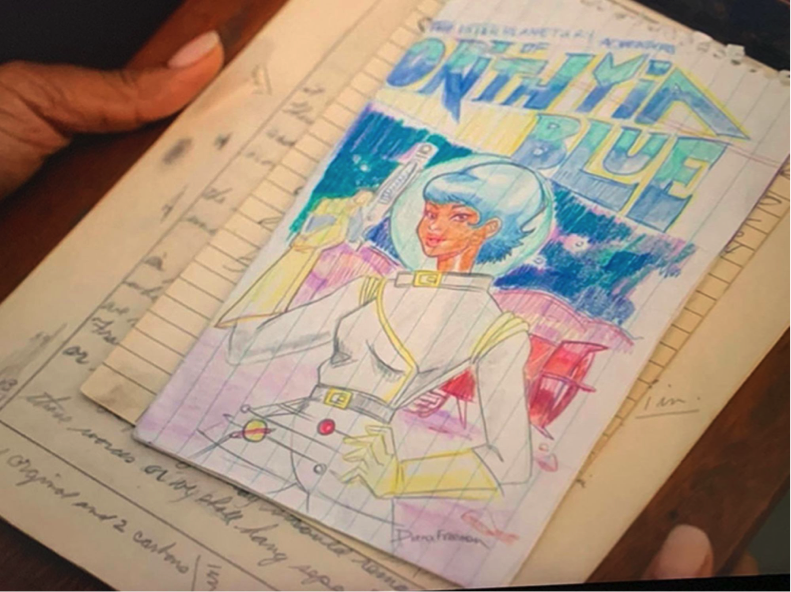

These robots are a pulp fiction dream made real. Young Dee Freeman’s hobby is hand-drawing comic books centered on a blue-haired astronaut (actually drawn by Black-Native artist Afua Richardson).

These robots are a pulp fiction dream made real. Young Dee Freeman’s hobby is hand-drawing comic books centered on a blue-haired astronaut (actually drawn by Black-Native artist Afua Richardson).

Dee literally makes her own mythology, visualizing storylines that the postwar culture industry would never have dreamed up or even allowed. This show wants to give those dreams a home. That home, perversely, is Lovecraft Country.

Dee literally makes her own mythology, visualizing storylines that the postwar culture industry would never have dreamed up or even allowed. This show wants to give those dreams a home. That home, perversely, is Lovecraft Country.

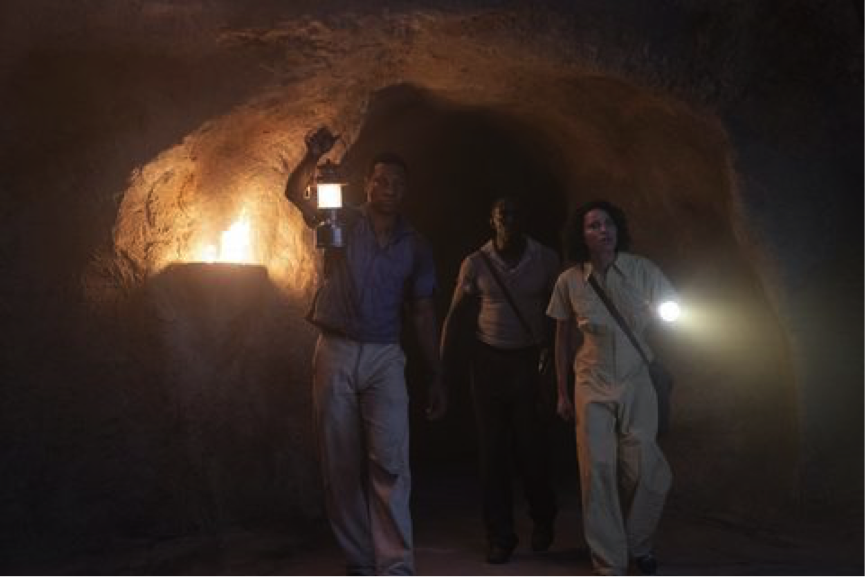

If Lovecraft Country has a lesson, perhaps it’s that its titular terrain is a place we’ve never properly explored. Somebody needs to open its secret passages, brave its dark tunnels, and do their darndest to avoid the boobytraps.

To state the obvious (and belabor my metaphor), white people cannot be the ones holding the flashlight— or least need to be cautious when sharing the labor of doing so. We seldom see the monsters as we should and tend to take up a strangely large amount of space in the corridor. Fortunately Misha Green, like other Black creators of our moment, has already shined a light that anyone who reads, thinks, and writes about religion would do well to follow. One might even try to translate her thinking out of television and into some other medium (like, to take a not-entirely-random example, a review essay).

To state the obvious (and belabor my metaphor), white people cannot be the ones holding the flashlight— or least need to be cautious when sharing the labor of doing so. We seldom see the monsters as we should and tend to take up a strangely large amount of space in the corridor. Fortunately Misha Green, like other Black creators of our moment, has already shined a light that anyone who reads, thinks, and writes about religion would do well to follow. One might even try to translate her thinking out of television and into some other medium (like, to take a not-entirely-random example, a review essay).

This is a show by, for, and about bookish nerds. It wants us to join it in its pulp reverie. I recommend giving in to its pleasures. Just don’t lose sight of the monster (or the riotous mob) creeping up behind you.

J. Barton Scott is an assistant professor at the University of Toronto and the author of Spiritual Despots: Modern Hinduism and the Genealogies of Self-Rule (University of Chicago Press, 2016).

***

[1] The author would like to thank Prof. Mimi Winick for bringing this image of the The Golden Bough into his life.