Queer Nuns and Digital Dragtivism in the Age of COVID-19

The Sisters of Perpetual Indulgence are spreading joy and pushing boundaries during the pandemic

A Sister of Perpetual Indulgence walks in the 2017 Stonewall Pride Parade in Columbus, Ohio. (Photo: Lauren Pond)

Amid the flurry of participants and floats in Ohio’s 2017 Stonewall Columbus Pride parade, one person caught my attention: a man dressed in drag and a headpiece that resembled a Roman Catholic nun’s coronet. Slowly processing down North High Street in a sundress and glitter-covered beard, he used a pink-gloved hand to give a royal wave to throngs of people on either side of the road.

When I learned the Revealer would be publishing a special issue on religion and fashion, I immediately flashed back to this individual, who, I’d since found out, was a member of the Sisters of Perpetual Indulgence. The Sisters – an international order of queer activists who playfully dress in the spirit of Catholic nuns and serve the community – seemed like a natural story to pursue. Their distinctive attire would make for a vibrant photo essay. I envisioned meeting the Sisters at public events, speaking with them about their ideas of fashion and religion, and taking their portraits.

Then March 2020 arrived, and with it, the COVID-19 pandemic. In-person gatherings were canceled, and the Sisters, like many Americans, went into isolation. A photo essay about them seemed like a moot point. However, the Sisters have since adapted their social activism to the age of social distancing, in many ways expanding possibilities for community outreach and fashion.

Founded in San Francisco in 1979, shortly before the AIDS crisis emerged, the Sisters of Perpetual Indulgence have “operated in the midst of a pandemic for the past 40 years,” explained Sister Purrr Do of the Indiana Crossroads Sisters, who, like many, goes by a witty or sexually suggestive name and uses female gender pronouns.

“This is our space,” she said. “We not only understand what to do in regards to service . . . when we show up, when we are visible, [we], through being present, are a reflection of beauty and joy.”

Fashion has been integral to the Sisters from the outset. The order began as a public performance by gay activists who were both reacting to the hyper-masculine “Castro Clone” look popular in San Francisco’s 1970s gay community and influenced by a growing local gay theater and dance scene. At the time, groups like the Cockettes were “flaunting the conventions of gender by mixing markers such as beards and dresses” and using white pancake makeup and glitter, recounts Melissa Wilcox in her book Queer Nuns. Feeling bored on Easter weekend in 1979, Ken Bunch (the co-founder of a drag troupe known for performing pom-pom routines in retired Catholic nuns’ habits), a former Catholic named Fred Brungard, and another friend decided to “terrorize the town” by dressing up in the nuns’ habits and makeup. They realized the shock and attention their looks elicited could be channeled toward social change. Not long thereafter, the Sisters of Perpetual Indulgence, and their unique style, were born. As of 2016, according to Wilcox, the Sisters were active in 22 American states and 12 countries, often through specific “houses,” or communities.

Portrait of Sister Anna Mae Ceres at a socially distanced, outdoor storytime event hosted by the Cincinnati Sisters in Ohio on June 20, 2020. (Photo: Lauren Pond)

Portrait of Sister MSG at a socially distanced, outdoor storytime event hosted by the Cincinnati Sisters in Ohio on June 20, 2020. (Photo: Lauren Pond)

Donning endless, playful interpretations of Catholic nuns’ habits, colorful accessories, and makeup, the Sisters blend the “familiar tropes of drag queen and female religious renunciant,” writes Wilcox, and engage in something she terms “serious parody.” They parody a religious institution that has historically opposed and oppressed the LGBTQ community while also demonstrating their interpretation of what it means to work as nuns: spreading joy, expiating guilt, exposing bigotry, championing human rights, and assisting the vulnerable and marginalized. The Sisters’ humorous, flamboyant appearance captures attention for these social causes, helps them engage with the public, and provides a protective layer of anonymity.

“You could think of us as a modern-day jester in some capacity,” Sister Purrr Do said. “We are these clown nuns, but we have the ability to speak truth to power in a way that many people may not be able to do.”

Sisters’ styles tend to vary, and no two Sisters look exactly alike. Some manifest – the term for getting dressed and made up, and assuming the persona of a Sister – in “high nun” fashion, wearing black robes and veils, said Sister Anna Mae Ceres (pronounced series), a member of the Cincinnati Sisters in Ohio. There is even a Sisters charity event called Project Nunway put on by houses across the country that highlights a variety of high-fashion looks.

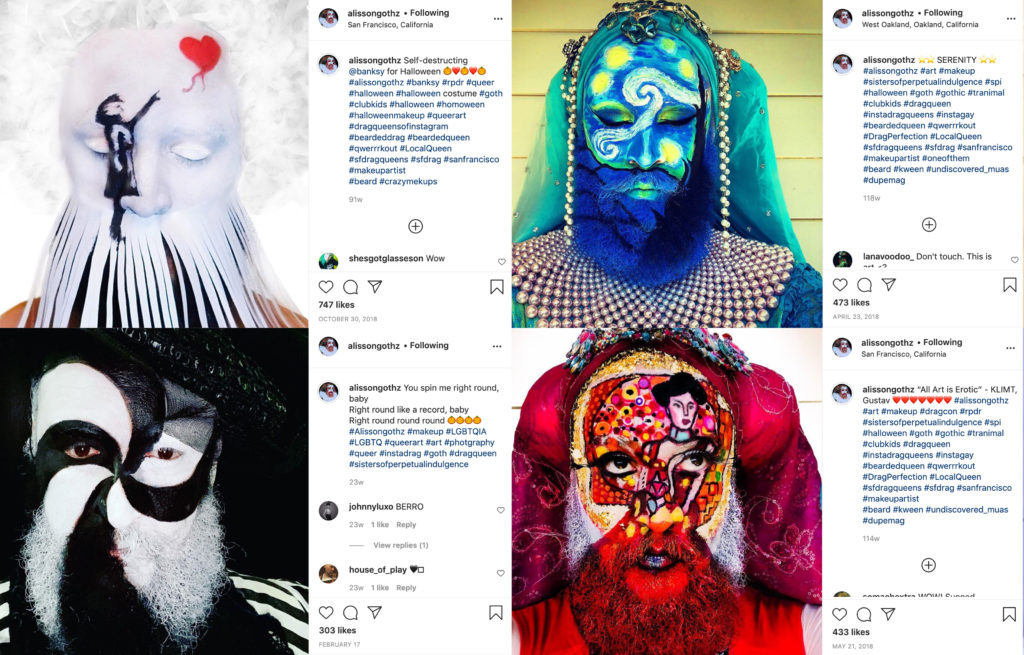

Anna Mae herself manifests as characters from the anime series Sailor Moon, and finds that dressing in this manner makes it easier for her to engage with younger audiences. Other Sisters prefer a simpler look: Wearing rosy clown cheeks, a floral-patterned dress, and a veil wrapped behind her head, Sister Freida Fondleus of the Kentucky Fried Sisters in Lexington, Kentucky, describes herself as an “approachable clown.” Part of the founding Sister community in San Francisco, Sister Tilda NexTime takes approximately four hours to manifest and uses water-based paints to replicate works of art, such as Van Gogh’s Starry Night, on her face.

“My idea is to be a walking piece of art that brings joy to people,” she said. “I really love doing that.”

Several portraits from the Instagram account of Sister Tilda NexTime, a member of the San Francisco Sisters of Perpetual Indulgence, who says she manifests with the intent of being “a walking piece of art that brings joy to people.” (Photo: Lauren Pond)

A Zoom call portrait of Sister Anna Mae Ceres, of the Cincinnati Sisters, during the COVID-19 pandemic. Anna Mae commonly manifests as characters from Sailor Moon. (Photo: Lauren Pond)

A screenshot portrait of Ken Tagious, a gender-fluid Brother from the Kentucky Fried Sisters, during the COVID-19 pandemic. Ken Tagious often manifests based on a feeling, aiming to express raw emotion and provoke questions about beauty. (Photo: Lauren Pond)

A screenshot portrait of Sister Freida Fondleus of the Kentucky Fried Sisters during the COVID-19 pandemic. Freida Fondleus says she commonly manifests as a friendly, outgoing, “approachable clown.” (Photo: Lauren Pond)

Sisters are quick to note that attire and make-up do not make the Sister; actions do. And these are many: Often, you’ll see manifested Sisters protesting for LGBTQ rights and countering antagonistic street evangelists; you’ll also find them advocating for immigrants and supporting the Black Lives Matter movement. Many Sisters have personal ministries they cultivate, such as providing resources for the homeless or support for individuals struggling with mental illness.

Then there are crises like pandemics. In the 1980s, as AIDS stigmatized and devastated the queer community, including members of the order itself, the Sisters engaged in advocacy, including a “stop the violence” campaign to address rising homophobic hate crimes. They also hosted some of the first fundraisers for people suffering financially as a result of the disease. Sisters are perhaps best known for their ongoing efforts to provide HIV education and sexual health resources, such as Play Fair! – a “hip, sexy, funny guide to safer sex,” Wilcox notes, “designed for gay men, by gay men.” The guide is distributed free of charge, sometimes with condoms and lube.

Amid the devastation of the COVID-19 pandemic, Sisters are likewise working to keep people healthy and support those impacted by the novel virus. Fashion continues to be a platform for this outreach. Notably, many Sisters are now incorporating masks into their ensembles, using fabric colors and patterns both as stylistic accents and to send a public health message.

“You can show people, if we can wear this over beards and makeup and all kinds of stuff, you can wear a mask as well,” Sister Tilda NexTime said.

At a socially distanced children’s storytime event led by the Cincinnati Sisters in June, Sister Anna Mae Ceres wore a black cloth mask lined with red, complementing her black dress and hot pink eye shadow and coronet. Earlier in the spring, she offered an online mask-making tutorial and encouraged PPE donations to healthcare workers; she and Sisters elsewhere have also sewn and sold masks, with proceeds benefiting charitable organizations.

Sister Arya Sirius reads a children’s book held by Sister MSG while Sister Anna Mae Ceres looks on during a socially distanced, outdoor storytime event led by the Cincinnati Sisters on June 20, 2020. Held in partnership with Downbound Books, the event raised money for Black Trans Femmes in the Arts. (Photo: Lauren Pond)

Cincinnati Sisters Anna Mae Ceres (left) and MSG (right) talk and look through children’s books before the storytime event in Cincinnati on June 20, 2020. (Photo: Lauren Pond)

Sister Arya Sirius holds her child at the Cincinnati Sisters’ storytime event in Cincinnati, Ohio, on June 20, 2020. (Photo: Lauren Pond)

“I mean, who doesn’t want to wear a rainbow mask with puppy paw prints?” Anna Mae said, noting some of her other fun purchases: fabric with cow print patterns, as well as fabric with patterns from the Lion King and the Nightmare Before Christmas.

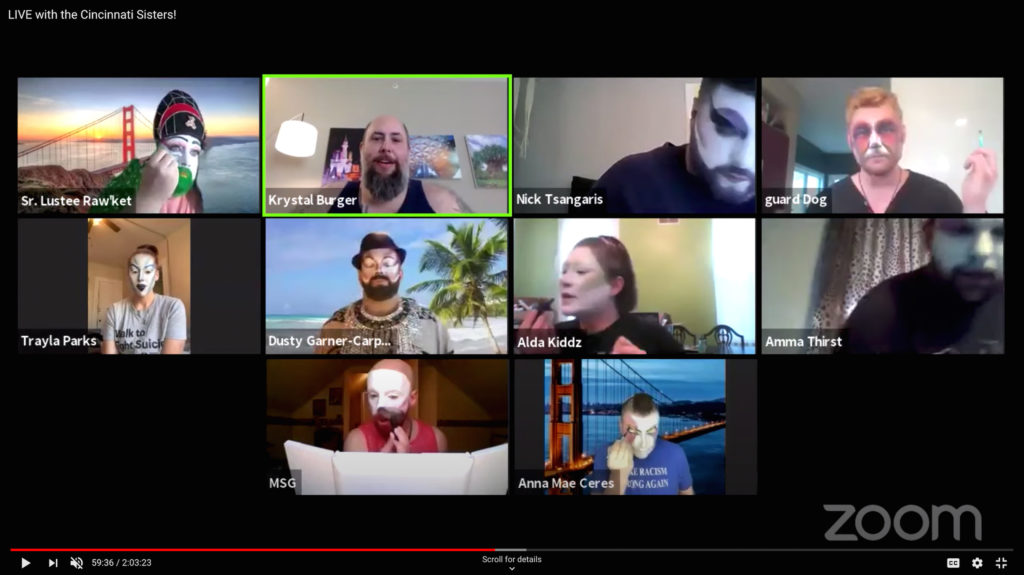

Since the pandemic began, Sisters have increasingly brought their distinctive appearances online, using digital fashion to entertain the public and buoy spirits at a distressing time. One common activity is applying makeup live on social media platforms such as Facebook and YouTube. As of May 2020, Anna Mae estimated that she’d “painted up” more than 20 times virtually, usually taking about 45 minutes each time. The Cincinnati Sisters also produced a video compilation inspired by TikTok’s viral #DontRush Challenge, capturing each person’s transformation from their “home attire” to their Sister attire. And in early April, a group of Cincinnati Sisters applied makeup during a public Zoom call, which was streamed on YouTube. Amid conversation and witty banter, they applied grease paint and eyeliner; some donned coronets. Audience members posted comments throughout the process.

“Thanks for doing this,” one person wrote in the live comment feed of the YouTube video. “Y’all have me laughing harder than I have all week.”

Occasions like this give the public a “glimpse behind the veil,” said Sister Purrr Do, who, until the pandemic, had rarely applied makeup online, but now loves the process. “In small-town Indiana, when our friends in the community tune in to watch us, they’re really intrigued at how we make this transformation happen . . . When they see our Sister selves, it is like seeing a magical clown creature in the wild.”

The Cincinnati Sisters apply makeup and socialize during a public Zoom call on April 10, 2020. (Photo: Lauren Pond)

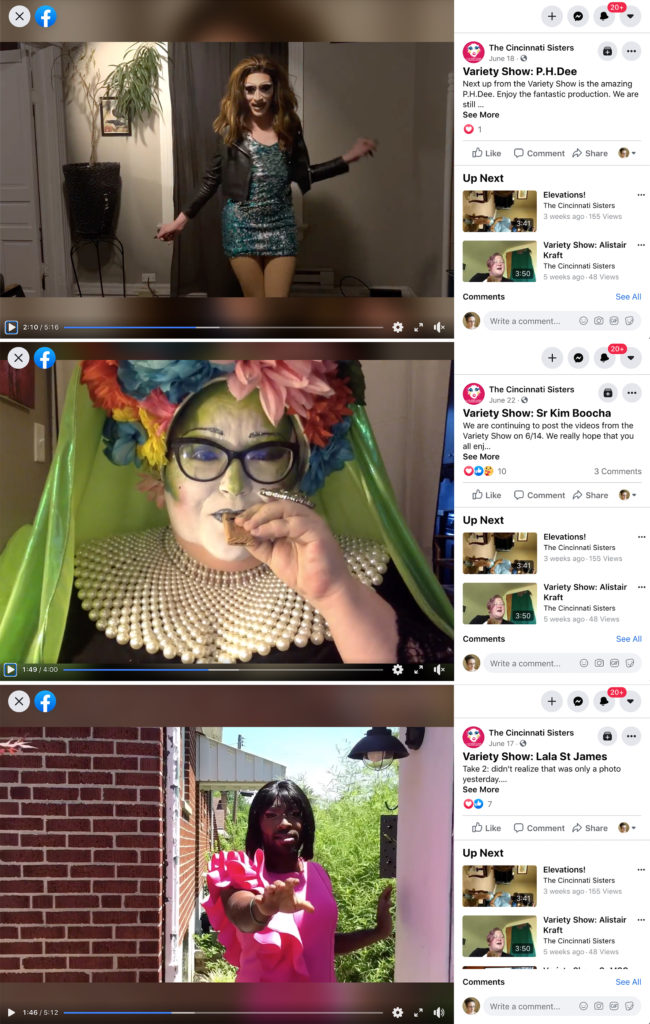

Sisters are also manifesting for digital events – both online versions of events that typically occur in person, and virtual events created specifically to assist, entertain, and uplift people during the pandemic. Through their Facebook pages, some Sister houses are hosting virtual drag, talent, and magic shows. Sister Freida Fondleus, still dressed as the “approachable clown,” has held virtual versions of her regular storytime sessions – which, focusing on poetry and literature by queer authors, advance her personal mission that “our stories are important.” Although most 2020 in-person Pride events were canceled or postponed, online festivals like “Chill In and Proud” sprang up in their stead, with Sisters participating.

Keeping with the Sisters’ tradition of fundraising, some of these Sister events have harnessed fashion to raise money for people suffering the effects of the pandemic’s economic downturn. For instance, the San Francisco Sisters’ annual Easter Hunky Jesus Contest – wherein participants dress as irreverent interpretations of Jesus and Mary – took place live on Instagram, Facebook, and Twitch, with proceeds donated to the Queer Nightlife Fund, an initiative supporting queer nightlife workers who have lost income.

Other Sisters have used these digital appearances specifically to support people of color and condemn the systemic racism that the pandemic has laid bare. The Cincinnati Sisters’ June variety show – featuring, among other acts, Sister Kim Boocha playing the kazoo in pearls and a colorful floral coronet, and lip-sync routines by drag queens P. H. Dee and Lala St. James – solicited donations for the Black Trans Protester Emergency Fund.

Screenshots of several acts from the Cincinnati Sisters’ June 2020 digital variety show, which raised money for the Black Trans Protester Emergency Fund. (Photo: Lauren Pond)

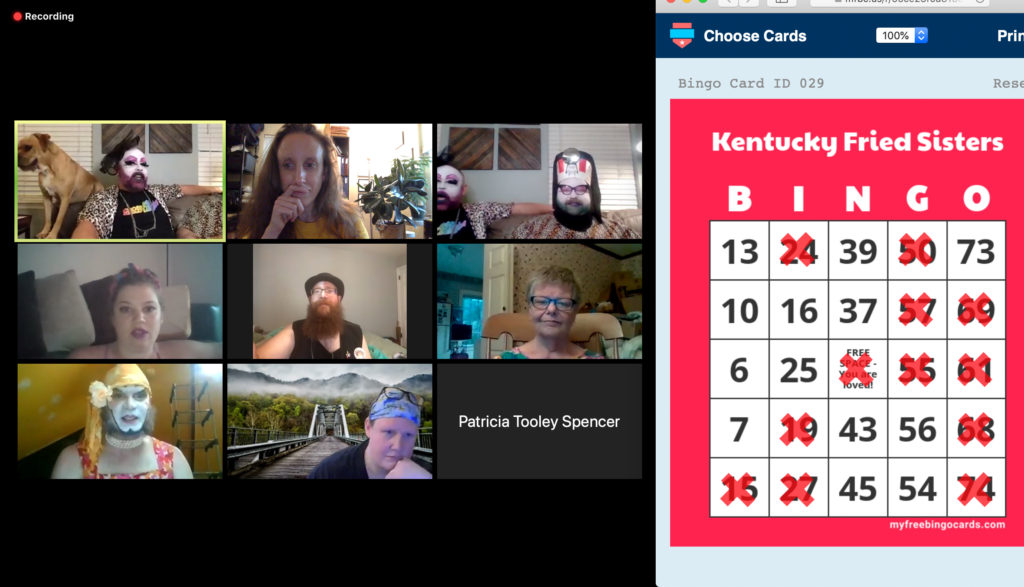

The Kentucky Fried Sisters host a virtual “Blessed Bingo” game on June 21, 2020. (Photo: Lauren Pond)

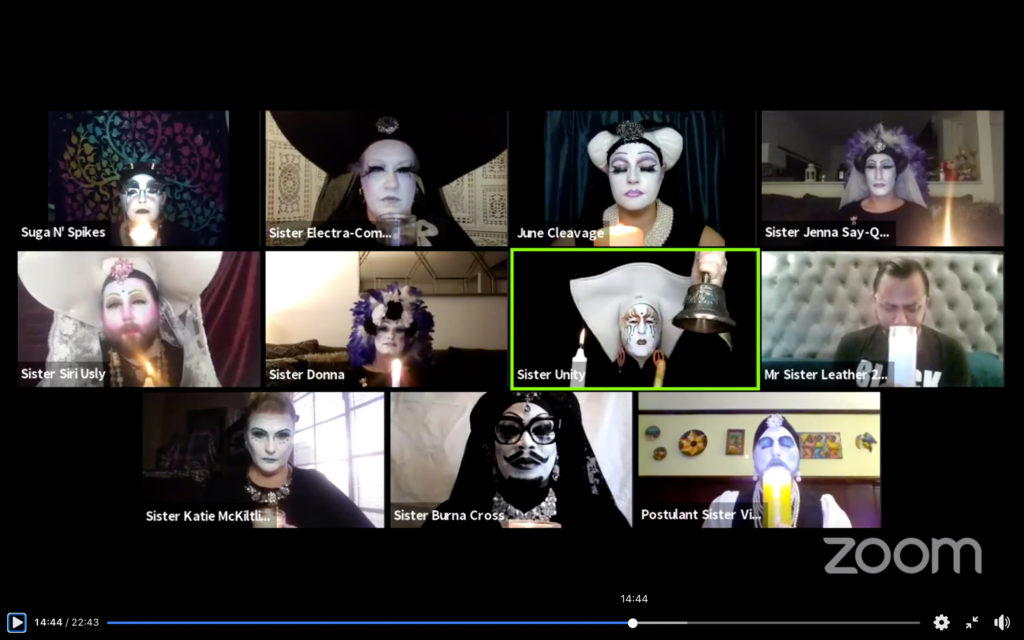

During the Kentucky Fried Sisters’ “Blessed Bingo: Pride Edition” event, Sister Freida Fondleus shared Black LGBTQ history after each round of the game. And on Juneteenth, manifested members of the Los Angeles Sisters of Perpetual Indulgence held a somber Zoom candlelight vigil wherein they read the names of Black Americans recently killed by police.

“Law enforcement agencies across the country have failed to provide citizens with even basic information about the lives they have taken,” said Sister Burna Cross – a Black Sister wearing a black veil, clear gemstones, and a painted handlebar moustache – shortly before the name-reading began. Sister Electra-Complex, her head covered in sweeping black coronet, continued: “We do this as avatars for healing.”

The Los Angeles Sisters of Perpetual Indulgence hosted an online vigil on June 19, 2020 for Black Americans recently killed by police. (Photo: Lauren Pond)

One concern in transitioning to this and other forms of digital “dragtivism,” as it were, is the lack of in-person interaction between the Sisters and the people who need their help: the homeless, queer people facing hatred and bigotry in rural America, and transgender youth, among others.

“For me, I’m like, am I still reaching who I need to reach and serving the community in the way I feel I need to be doing it?” said Ken Tagious, of the Kentucky Fried Sisters, who identifies as a gender-fluid Brother, rather than a Sister. “That’s a tough question and a tough answer.”

Additionally, for Sisters who normally draw their inspiration from in-person events, the transition to these online appearances has been a challenge – even a barrier to their usual activism, Sister Anna Mae Ceres explained. “There are some Sisters right now who don’t feel like they can manifest, because they just don’t have that energy,” she said.

But most of the Sisters I interviewed expressed optimism – even gratitude that the pandemic has forced the shift to online outreach. In bringing Sister fashion to digital platforms, and in encouraging the development of websites and a stronger social media presence, the pandemic has necessarily ushered their houses into the digitally networked era. Establishing a virtual presence has enabled Sisters to interact more with each other, build a larger following for the order – nationally and globally – and consider how they can use technology to advance their outreach when the pandemic eventually subsides.

“There are people that follow the Sisters because of the way we look,” Sister Tara NuHole, of the Indiana Crossroads Sisters, said. “We get so many follows and likes and shares because of just the way we are presenting ourselves. Luckily, the bonus feature that comes with that is our message gets shared, too.”

Some are just grateful for the comforts of getting dressed and made up at home. “If you want the real truth,” Sister Purrr Do said, “for the last three months, I have manifested and not worn pants the entire time. As long as the camera is trained from here up, that’s the only thing that’s got to be pretty.”

Lauren Pond is a documentary artist whose work explores the intersection of religion, culture, and human experience. She is the Multimedia Producer for the American Religious Sounds Project and published her first book, Test Of Faith, in 2017.

***

Published with support from the Henry R. Luce Initiative on Religion in International Affairs.