Priest Migration to Save Italy’s Catholic Churches

Italian bishops are hiring priests from Africa, South America, and elsewhere to address a priest shortage. But the migrant priests face persistent racism and anti-immigrant attitudes.

(Image source: Unsplash)

On a sweltering Wednesday in August, Father Vincent Chukwumamkpam Ifeme strolls familiarly into a beachside restaurant in Italy. A ring inscribed with the lyrics to “Ave Maria,” Jesus sandals, and a cross pin on the lapel of his navy-blue polo are the only visible indications of his vocation. His other accessories are more modern—a sleek black Apple watch and Ray Bans. His black beard is peppered with white. “I think when Italians see somebody like me come in,” he says as we assess the menu, “that some people are curious to know, what do I have to offer that is different from what they already have?” His voice is deep and buoyant, each word lilted up with its own question mark. The restaurant, Ristorante Chalet Stella, sits facing the sea in San Benedetto Del Tronto, a town of 47,000 inhabitants on Italy’s Adriatic coast. Father Vincent is the only Black man in the sparsely populated restaurant. And before he stepped into the eatery, he was the only Black man visible on the beach.

He orders spaghetti alle vongole, a house salad, and a glass of white wine.

Father Vincent heads a parish in the nearby commune of Monteprandone, a village of 1,500 residents that dots the countryside 20 minutes from the sea. Some 90% of the locals are Italian. His congregants call him “Don Vincente” or just “padre.” He beckons fondly to them as they pass and exchange stories with emphatic syllables. He has mastered the critical Italian art of affable banter. His booming laughs come easily. Most of his parishioners are old women, he says.

Father Vincent is part of an emerging trend in Italy that brings priests of foreign nationalities into short-staffed parishes, sometimes to serve Italians and sometimes to tailor services to a particular community of immigrants. Italy, and the Catholic church in particular, is experiencing a demographic problem. The country’s population is growing older and birth rates are plummeting to record lows. In 2022, seven Italians were born for every 12 dead. The church, too, is losing parishioners. While nearly four out of every five Italians consider themselves Catholic, only one in five attend services on a weekly basis. With fewer practicing the faith, even fewer are following it to the vocation. In the last three decades, Italy has seen a dramatic drop in new priests: 20% fewer are serving now than were in 1990. Preti stranieri, or foreign-born priests, are part of the church’s concerted effort to embrace interculturality as a means of survival. Integrating them into Italian parishes invites immigrants into the institution at the heart of Italian culture.

But Italy, a country steeped in anti-immigrant sentiment, might not be ready to accept the change.

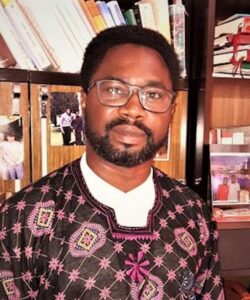

(Father Vincent Chukwumamkpam Ifeme. Soucre: Berkeley Center)

When he is not bantering, Father Vincent speaks with a casual but weary brilliance. He has always been at the top of his class. In his hometown of Umuchu in southeastern Nigeria, he grew up attending a private Catholic school. His father died when he was two, leaving just his mother to raise him. The priests on campus were a support system, and the curriculum of the school, called a junior seminary in Nigeria, was meant to show students that they could follow in their footsteps. But when he arrived in Italy 1996 to attend Pontifical Urban University in Rome, Father Vincent still wasn’t sure about the priesthood. “I didn’t have internal peace. So, I just felt that maybe God started telling me this is the way, this is what I’m calling for.” There is a good-spirited resignation in his voice. He received a scholarship at age 23 to continue his studies, sponsored by his home diocese in Nigeria. He had just completed his first degree in philosophy at a seminary in Umachu, as well as a year of pastoral service. For his next degree, he would study theology.

Umachu is located in a part of southern Nigeria that is dominated by the country’s minority Catholic population. Twelve percent of Nigerians consider themselves Catholic, while half identify as Muslim. Most of the Catholic population resides in the Southeast, primarily populated by faithful Igbo people, one of the tribes local to the Nigerian land. A 2023 study out of Georgetown University found that 94% of Nigeria’s 30 million Catholics attend mass at least weekly.

The country is young in many ways Italy is not: the median Nigerian age is 19, and the nation itself is only 63 years old. Nigeria’s youth is reflected in the way people worship, says Father Vincent. Youth initiatives are abundant in their practice, and masses are filled with upbeat music and imbued with spiritual mysticism. In Italy, the church is bogged down with traditions that do not appeal to the young, says Father Vincent, like ritual-heavy celebrations and long masses with dreary sermons. “The young people see the church as something for the old people. You have to invent things that attract them to come to the church. But in Nigeria it is completely the opposite.” Across all of Africa, the total number of priests is increasing by more than 1,000 each year. In Europe the number is decreasing twice as quickly. Father Vincent was one of 2,631 preti stranieri serving in Italy in 2022, up tenfold from just 204 in 1990.

(A cohort of 11 Nigerian priests commissioned for mission in Europe in June 2024. Image source: CSN Media)

Under Pope Francis, the first pope from the Americas and from the Southern Hemisphere, church interculturality and support for migrants have been clear priorities. “Especially in this last 100, now 150 years, the church is focused on taking care about migrants and later she started also to take care about refugees,” says Father Mussie Zerai Yosief, whose dedication to advocacy for refugees has earned him the nickname “the migrant priest,” and a nomination for the Nobel Peace Prize. “We have the same church, where there is the need, we will go to serve,” says Father Mussie. “Saint Peter, Saint Paul —all the apostles — he’s not from Italy, he’s not from Europe. He was from the Middle East. So it’s not new.”

When he arrived in Italy, Father Vincent didn’t speak a word of Italian. He started classes entirely in the new language with only a short intensive to equip him with the basics. After his masters, he started a Ph.D. in Dogmatic Theology and was ordained in 2003 while on a short stint back in Nigeria between his studies. To pay his keep through the last two years of his doctorate, he took up a role in 2005 helping out the parish priest at a church in another rural, countryside town (of which Italy has no shortage) called Castigliano. In 2007, eleven years after first arriving in the country, he received his Ph.D. By that time, he had picked up work in the quiet Marche region where we met for lunch. He spent years there re-signing the three-year contracts that are standard for priests working outside their diocese of origin. He tried to grow roots. His mother moved to Italy, and he gradually earned more and more responsibility in his parish, starting as a deputy parish priest and then in 2012, a parish administrator in Rotella, a half-hour drive into the hills from San Benedetto del Tronto. It wasn’t always easy.

In Father Vincent’s early years in Rotella, he was often turned away by Italians while making house calls to deliver Last Rites or to hear confessions from the sick and dying. Because of the causal nature of the seaside village, he rarely wore his Roman collar on these visits, the clearest external signifier of his priesthood, and it was a time before he was well known in the community. Italians often turned him away, mistaking him for one of the many African migrants who go home-to-home selling cheap bracelets, plastic beach toys, or sandals. Ignoring dismissals, he would rap on doors and windows and attempt to explain. “They do not know your face,” he said. “They only know you’re a Black man.”

After several contract renewals, he hit a ceiling for how much he could progress in Italy as a priest ultimately under the charge of another diocese. Bishops in Italy were hesitant to give him senior roles because they were unsure he would be allowed to stick around by his Nigerian bishop, who has authority over his placement, and without citizenship he wasn’t allowed to sign off on church legal documents. An individual from town had to be hired to act as his signatory. The dance became dizzying and colored with frustration. By this time, he had spent more than a decade in the country. Italy had become a home to him and back in Nigeria, where the church was still growing, he felt his services were not needed. He believed it was part of his priestly calling to breathe new life into the faltering Italian faith. Ultimately, Father Vincent made the decision to leave his home diocese and become officially integrated into his Italian diocese. And then later, he went through the laborious process of obtaining his Italian citizenship. Now, his responsibilities have expanded, seemingly endlessly. He teaches university courses nearby his parish, and once a week drives into Rome to teach theology at his alma mater, in addition to attending to his pastoral duties and heading up the office of interreligious dialogue and ecumenism for his diocese. He is the only priest in Monteprandone with a doctorate, so his bishop often taps him for responsibilities calling for some added prestige or intellectual heft.

Father Vincent still considers Umachu his home, but he does not plan to leave Italy now. He returns to Africa each year, save a few stalled trips during COVID or particularly dangerous bouts in Nigeria’s history. He flies into Lagos and makes the 8-and-a-half-hour trek home by car. In part, he goes to learn. “I’m of the conviction that Nigeria can enrich the Catholic experience here in Italy and Italy can also enrich the Catholic experience in Nigeria and other countries,” he says. Some Italian churches have already explored the possibility of sharing space and tradition with brothers and sisters from across the globe.

***

On Sundays on the outskirts of Rome, Chiesa di Santi Simone e Guida Taddeo explodes with vibrant colors and rich, upbeat melodies. The pews are packed with locals of Nigerian descent, outfitted neat suits, patterned dresses, sunglasses, and headscarves. Many have commuted from other parts of Rome’s sprawling metropolis to this small, holy structure. Father Ugochukwu Stophynus Anyanwu, in trendy black tennis shoes and traditional robes, mans the pulpit. He delivers a lively mass to the crowd, warning of the perils of Facebook as a minefield of false idols. “Technology and people will betray you, only talk to God,” he said. The service is modern and lively. On an unforgiving summer day, the worship carries a cool relief. “I have to give kudos to the church in Rome,” said Father Ugochukwu, “Wherever we find ourselves we, as much as possible, try to accommodate everyone so that they can also share in the community faith.”

The outpost is one of 900 or so Catholic churches in Rome and sits off the main artery of Torre Angela, a neighborhood of dirt and concrete, seven miles and several millennia removed from the city. It is a primarily Italian parish that hosts a community of Nigerian worshipers on Sundays, under the services of Father Ugochukwu, who acts as a chaplain. He is one of many preti straineri who have taken up roles in Italian parishes specifically with the intention to serve congregants that share their cultural background. His counterparts across the country range from Congolese and Ethiopian to Ukrainian and Filipino. They have a Whatsapp chat.

Father Ugochukwu was born in Nigeria, in the same majority Catholic region as Father Vincent. He has been in this role only four years, having arrived during COVID to study. He speaks with youthful excitement about big ideas. As he speaks to me in English, he integrates Italian phrases, “piano, piano,” to mean slowly but surely, and “sentirsi a casa, lontano da casa,” to mean feeling at home, far from home.

His class of student clergy are part of a push by Pope Francis to get all those educated in Rome’s Catholic churches involved in pastoral work as well. “Pastoral work” is somewhat universal—whether you’re in Italy or Nigeria or Indonesia—and includes meeting with parishioners for support like counseling, last rites or marital consults, helping services run smoothly, and a bit of run-of-the-mill church maintenance like sweeping floors and organizing prayer books. The students gathered in recent years with the Pope for a pep talk. The gathering was bursting with thousands of young practitioners of the faith, touching shoulders in a large hall. With nearly 6,000 priests in attendance, “we are making a joke that even the priests in Rome are more than the lay faithful,” says Father Ugochukwu. Pope Francis had a clear message for his staff: “He says he wants every one of us to get attached to a parish,” says Father Ugochukwu.

For those preti stranieri that don’t master the language, this can mean taking on menial tasks at parishes—keeping the church tidy, cleaning the stained glass. It’s up to the Italian bishops to determine what, and who, the churches in their dioceses need on hand. Relationships between bishops in Africa and bishops in Italy, for example, can precipitate a personnel exchange. If an Italian bishop is short staffed, they can call up a colleague on another continent and ask if they have any surplus clergy to help out. Or, in the case of students, they can use their academic or personal networks to find a church that could use a little extra help, then get the ball rolling by facilitating dialogue between the two bishops (that of their home diocese and that of their prospective diocese.) These arrangements are usually temporary—contracts need renewal after three years. With fewer Italians joining the priesthood and the existing Italian clergy aging out, bishops are turning toward their southern neighbors: “Africa appears to be the springtime of vocation ….that’s why Africa is always supposed to send workers wherever they are needed,” says Father Ugochukwu.

Each diocese attached to Rome also has an office of migrants, meant to cater to the needs of Catholic newcomers. The office arranges host communities for people with shared backgrounds and ways of worship and tries to pair these outposts with a chaplain that can lead masses tailored to the language and tradition of each group. Nigerian masses are filled with percussion and choir; Ethiopian masses are somber, and their music chimes with bells and soft songs.

The work of building niche community parishes feels like a separate mechanism to that of preti stranieri serving in majority Italian parishes, but the two initiatives work together toward a strategic objective: empowering a global church. Fostering migrant communities helps to fashion a church that offers a safe space to anyone, anywhere. Preti straineri leading Italian parishes often see themselves undertaking a distinct, but related task: reviving the ailing Italian church. They tend to hail from countries that have historically been on the receiving end of Catholic missions like Nigeria—many hail from Ghana, the Philippines, and India. Some see their work as a sort of reverse mission, revitalizing the gospel in the very societies that first delivered it to their ancestors. But there is no clear signal these efforts are working, as Italian participation in the church continues to decline. Instead, these new church leaders serve the remaining devoted and help to run the massive Catholic infrastructure that still exists in the country: running charities, serving migrant populations, performing marriages, and visiting hospital beds for the sick and dying.

Experts who have been studying the trend, like Arnaud Join-Lambert, a scholar of theology at the Catholic University of Louvain, cringe at the phrase “reverse mission.”

“It has to do with mission,” he concedes. “Okay, that’s true.” But it’s more about creating a new, universal church, one that really embodies the idea of meeting worshipers where they are, rather than revitalizing the gospel, he says. The first Catholic missions were motivated by a Western idea of “civilization”—of “civilizing” indigenous, often tribal peoples. The missions were intimately tied up with colonization.

Instead, Join-Lambert sees this wave of priestly migration as an attempt to construct an intercultural church. In the image of Pepsi or McDonald’s, the Catholic Church isn’t looking for a new market—its executives are strategizing to seamlessly integrate its global hubs for maximum efficiency.

The reverse mission is a romantic idea, says Annalisa Butticci, a professor of religious anthropology at Georgetown University, but it isn’t quite panning out.

“I don’t see this happening anywhere,” she says. “Especially in Italy, where there is such ingrained racism. It is kind of unlikely that Catholics will trust or will acknowledge the ministry of non-Italian priests.”

This friction was echoed in a 2022 open letter written collectively by preti stanieri who had gathered for a refresher course for foreign-born missionaries. The signatories shared similar experiences to Father Vincent and Father Stephen, writing “When it comes to our inclusion in the parish communities, especially at the beginning, we noticed a distrust and sometimes even coldness on the part of the people.” They describe the tiredness of the old church and its elderly congregants: “the aging of the participants, the small presence of young people, a certain sense of superiority,” and in some cases elderly clergy, “who tend to conserve and are afraid of new things.”

The capital city is two and a half hours from Father Vincent’s idyllic hilltop church. The mountain roads he traverses on his way to the other side of the continent crisscross dozens of ridges and valleys packed with homesteads and small, community churches. Many are missing priests. Father Vincent has begun to help facilitate more partnerships between Italian churches and Catholic churches abroad. In practicality, that means staffing those empty hillside pulpits. He sees it as an essential task to revive the Catholic faith in Italy; the efforts have been somewhat stifled by prejudice, from both bishops, who oversee the assignment of priests, and reticence from parishioners.

In 2012, he helped two young men from Nigeria take on roles in a rural parish as part of an arrangement to continue their studies following their master’s degree programs in Rome, much like he had during his early years in Italy. But after five years in the country, the men still had not felt welcomed by the parishioners or the host bishop. One of the men, Father Eugene, recalled one instance in which an elderly woman from a nearby village was dying while he was on the job. She wanted to see a priest, “but not that black priest.”

“This woman died without seeing a priest,” he says. “The woman was buried without mass.”

Both men returned to their home dioceses in Nigeria shortly after graduation, despite the high need for faith laborers in Italy. “Because you always feel sei straniero, because in Italy sei straniero,” said Father Vincent, meaning roughly: you always feel you are an immigrant, because in Italy you are an immigrant. And despite the promise of young, eager international priests to serve in Italian parishes, many bishops are reluctant to open their doors. “I come from a place where we still have a lot of vocations. I think most of them will be willing to come to Italy if they are invited,” says Father Vincent. “There’s a general lack of openness to accept that Italy needs new evangelization by new missionaries that are non-Italian.”

Italy’s long fomenting anti-immigrant rhetoric, mirrored throughout populist movements in Europe and the United States, encourages a suspicion around the motivations of migrants. It’s an assumption that follows foreign-born priests, casting them as opportunists, said Buttici. People assume “they are priests just because they want to leave their country, or they want to leave their family,” she says.

Preti stranieri joined the mission for a slew of reasons, a 2023 study in the Qualitative Sociology Review found. Priests cited a commitment to serving the church—unsurprisingly—and aspirations of economic stability as primary drivers. And in any job market, you go where there is work. Arnaud, the French scholar, said that African priests who may struggle to find a place in their region often opt to come to Europe as students, then search for a diocese in need. In Rome, this is a particularly accessible course because there is a novella-length menu of religious universities.

The skepticism and dismissal of preti stranieri are reflective of the challenges faced by migrants across Italy and much of the European Union. Italian leaders have expressed an understanding of the value a young, willing workforce of migrants offers the aging population. An agreement signed with Tunisia in October of 2023 streamlined the visa and residence permit process for workers from the nation and the quotas for working permits issued to non-EU citizens have risen dramatically over the last few years — up 150% from years before.

But these changes are happening against a backdrop of negative public sentiment toward migrants and continued high-profile clashes along the southern border. As in the case of preti stranieri, real progress integrating migrants and getting them to stay in Italy—rather than move along to more welcoming European countries—is slowed by turgid legal processes for obtaining work and residence permits, unsubstantial aid pathways and ingrained racism. “If you are an African, first of all, [Italians] see you as maybe somebody who has come here, maybe because you need something, or maybe because you are looking for help,” says Father Vincent.

Father Vincent, who took the time to integrate into Italian society and has taken on greater and greater responsibilities in the church and community, is a rare breed. More often, racism and paperwork wear down even the most eager evangelists.

Father Ugochukwu is learning German.

Carmela Guaglianone is a recent graduate of the Global Journalism masters program at NYU. She is a freelance journalist and Gigafact Fellow with the Arizona Center for Investigative Reporting.